Two

scholars at the New School for Social Research published an article

about literature and empathy last month, full of bad news for mystery

readers. If you belong to Sisters in Crime and saw the most recent

SinC Links, you may have noticed the references to

"Different Stories: How Levels of Familiarity with Literary and Genre Fiction Relate to Mentalizing."

The authors, David Kidd and Emanuelle Castano, say people who read

novels by authors such as Alice Walker and Vladimir Nabakov excel on a

test of "theory of mind," indicating they have superior abilities "to

infer and understand others' thoughts and feelings." Such readers are

likely to be characterized by "empathy, pro-social behavior, and

coordination in groups." Readers of mysteries and other genre fiction

don't do as well on the test. So apparently we're an obtuse,

hardhearted, selfish bunch, and we don't play well with others.

This

is grim stuff. And maybe I'm exaggerating a bit. I made myself read the

whole study--and let me tell you, the experience didn't do wonders for

my levels of empathy. Kidd and Castano don't actually say genre readers

suffer from all those problems. In fact, they speculate that reading any

kind of fiction may do some good. But they definitely think reading

literary fiction does more good than reading genre fiction does.

Literary fiction, they say, has complex, round characters, and that

"prompts readers to make, adjust, and consider multiple interpretations

of characters' mental states." Genre fiction relies on flat, stock

characters and therefore doesn't encourage readers to develop comparable

levels of mental agility and emotional insight. The authors discuss

other differences, too--for example, they say literary fiction features

"multiple plot lines" and challenges "routine or rigid ways of

thinking," while genre fiction is characterized by "formulaic plots" and

encourages "conventional thinking." I won't try to summarize all their

arguments. It would take too long, and it would get too depressing.

I

will say a little--only a little--about their research methods. To

distinguish between literary readers and genre readers, Kidd and Castano

put together a long list of names--some literary authors, some genre

authors, some non-authors--and asked participants to check off the names

with which they were familiar. People who checked off more names of

literary authors were classified as readers of literary fiction,

and--well, you get the idea. To determine levels of empathy and other

good things, Kidd and Castano had participants take the

"reading the mind in the eyes" test:

Participants looked at pictures that showed only people's eyes, looked

at four adjectives (for example, "scared," "anxious," "encouraging," and

"skeptical"), and chose the adjective that best described the

expression in the pictured eyes. Participants identified as readers of

literary fiction did a better job of matching eyes with adjectives.

Therefore, they're more empathetic and perceptive than readers of genre

fiction.

It's

not hard to spot problems with these research methods. Scottish crime

writer Val McDermid does a shrewd, funny job of that in a

piece also mentioned in

SinC Links.

(Among other things, Val says she took the "reading the eyes in the

mind" test and got thirty-three out of thirty-six right, beating the

average score of twenty-four. Just for fun, I took the test, too, and

scored thirty-four. That may prove I'm one point more empathetic than

Val. Or it may prove the test is silly.) And of course decisions about

which authors are "literary" and which are "genre" can be subjective.

Kidd and Castano talk about how they wavered about the right category

for Herman Wouk.

The Caine Mutiny won a Pulitzer Prize, so maybe Wouk's a literary author. On the other hand, some critics accuse

Mutiny

of "upholding conventional ideas and values," so maybe he's merely

genre. (Kidd and Castano never consider the question of whether a

knee-jerk rejection of all ideas and values currently judged

"conventional" might sometimes reflect a lack of insight and empathy. Is

sympathy for people who devote their lives to military service

automatically shallow and nasty? Is portraying an intellectual as a

fraud never justified?)

As for their method of classifying participants

as either "literary

readers" or "genre readers," I recognized the names of almost all the

authors on both lists. I've heard of James Patterson--most

people have--but I've never read a book of his; I don't think I've

sampled a single page. With many other authors (both "literary" and

"genre"), I've read a few pages, a few chapters, or a single story, and

then I've put the book aside and never picked it up again. Recognizing

an author's name isn't evidence of a preference for a certain kind of

fiction. For heaven's sake, how many people make it through middle

school without reading

To Kill a Mockingbird? So how does

checking off Harper Lee's name on a list indicate a preference for

literary fiction? (For that matter, some might argue

To Kill a Mockingbird

is crime fiction, and Lee therefore belongs on the genre list. It could

be that Kidd and Castano consider crime fiction that's well written

literary. If so, that's sort of stacking the deck against genre--if a

work of genre fiction is really good, it no longer counts as genre.)

It

may be--and I'm certainly not the first person to suggest this--that

social science's methods aren't ideally suited to analyzing literature,

or to determining its effects on our minds and souls. Social science, by

its nature, seeks to quantify things in exact terms. Maybe literature

and its effects can't be quantified. Maybe attempts to measure some

things exactly are more likely to lead us astray than to enlighten us.

As Aristotle says in Book I of the

Ethics, "it is the mark of an

educated [person] to look for precision in each class of things just so

far as the nature of the subject admits; it is evidently equally foolish

to accept probable reasoning from a mathematician and to demand from a

rhetorician scientific proofs."

If

social scientists can't help us understand the connection between

literature and empathy, who can? Perhaps a poet. In 1821, Percy Bysshe

Shelley wrote "A Defense of Poetry" in response to a friend's largely

playful charge that poetry is useless and fails to promote morality. I

think we can apply what Shelley says about poetry to fiction, including

genre fiction. After all, Shelley declares that "the distinction between

poets and prose writers is a vulgar error," and he considers Plato,

Francis Bacon, and "all the authors of revolutions in opinion" poets. So

why not Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammet?

I'm going

to quote several sentences from "A Defense of Poetry," and I'm not

going to make Shelley's choice of nouns and pronouns politically

correct. I tinkered with Aristotle's words a bit--it's a translation, so

tinkering felt more permissible. But I'll give you Shelley's words (and

his punctuation) without amendment:

The

whole objection, however, of the immorality of poetry rests upon a

misconception of the manner in which poetry acts to produce the moral

improvement of man. . . . The great secret of morals is love; or a going

out of our nature, and an identification of ourselves with the

beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person, not our own. A

man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he

must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains

and pleasures of his species must become his own. The great instrument

of moral good is the imagination; and poetry administers to the effect

by acting upon the cause. . . . Poetry strengthens the faculty which is

the organ of the moral nature of man, in the same manner as exercise

strengthens a limb.

As far as I

know, Shelley compiled no lists, administered no tests, and analyzed no

statistics. Even so, there may be more wisdom in these few sentences

than in any number of studies churned out by the New School for Social

Research, at least when it comes to wisdom about literature.

For

Shelley, literature's crucial moral task is to take us out of

ourselves. Most of us spend much of our time focusing on our own

problems and feelings. When we read, we get caught up in a character's

problems and feelings for a while, seeing things through that

character's eyes and sharing his or her emotions. This vicarious

experience is temporary, but Shelley says it does us lasting good. I

like his comparison of reading and physical exercise. Working out at a

gym makes our muscles stronger, and that means we're better able to

handle any physical tasks and challenges we may encounter. Reading gives

our imaginations a workout and makes them stronger. If we feel the

humanity in the characters we read about, we're more likely to recognize

the humanity in the people we meet. Will we therefore be kinder to them

and try harder to make sure they're treated justly? Shelley thinks so.

But

won't literary fiction, with all its round, complex characters, give

our imaginations a more vigorous workout than genre fiction will? To

agree to that, we'd have to agree to Kidd and Castano's generalizations

about literary and genre fiction, and I think many of us would hesitate

to do so. Yes, the characters in many mysteries are pretty flat, but

couldn't the same be said of the characters in many works of literary

fiction? Val McDermid challenges some of Kidd and Castano's central

assumptions about literary and genre fiction, and I think she makes some

persuasive arguments. I won't repeat those here, or get into the

question of to what extent current distinctions between "literary" and

"genre" have lasting validity, and to what extent they reflect merely

contemporary and perhaps somewhat elitist preferences. (Would Fielding,

Austen, the Brontes, Dickens, and other still-admired authors be

considered "literary" if they hadn't been lucky enough to die before the

current classifications slammed into place? Would they be consigned to

the junk heap of genre if they were writing today? But I said I wouldn't

get into that. I'll stop.)

I'll

raise just one question. Shelley says that to be "greatly good," we

must imagine not only "intensely" but also "comprehensively,"

identifying with "many others." If he's right, fiction that introduces

us to a wide variety of characters and encourages us to identify with

them may exercise our imaginations more effectively than fiction that

limits its sympathies to a narrower range of characters.

Generalizations

are dangerous, and I'm neither bold enough nor well read enough to

propose even tentative generalizations about literary and genre fiction.

(And when I say "genre," I really mean "mystery," because I know almost

nothing about other types of fiction currently classified as

"genre"--though I've read and admired some impressive urban fantasy

lately.) All I'll say is that I'm not sure all contemporary literary

fiction encourages readers to empathize with many different sorts of

characters. Most of the recent literary fiction I've read seems to limit

sympathy to intellectual characters with the right tastes and the right

opinions. Even if the central character is a concierge from a

lower-class background (probably, many of you will recognize the novel I'm

talking about), she has to be an autodidact who's managed to develop

tastes for classical music, Russian literature, and Eastern art, who

turns her television on only to trick her bourgeois employers into

thinking she fits their stereotypes. Two other characters who are

portrayed in a positive way, a troubled adolescent girl and a wealthy

Japanese gentleman, are in many respects variations on the concierge,

with similar tastes and opinions; most of the other characters in the

novel invite our disdain rather than our sympathy. How often does

contemporary literary fiction encourage us to empathize with characters

such as a concierge who actually enjoys television, reads romances, and

adores Garth Brooks and Thomas Kinkade? George Eliot could have

portrayed that sort of character in a genuinely empathetic way. I don't

know if many authors of recent literary fiction would have much interest

in doingso.

I

think some--not all, certainly, but some--genre fiction encourages us

to extend our sympathies further. I think many mysteries, for example,

introduce us to a variety of characters, including characters who aren't

necessarily intellectuals, flawed characters we might be tempted to

shun in our day-to-day lives. Mysteries can help us identify with people

who have made bad choices and taken wrong turns, with victims, with

people caught in the middle, with people determined to set things right,

with people who feel overwhelmed by circumstances. I can't cite any

studies to support my suggestions, but I think the best

mysteries, by portraying a wide range of characters and nudging us to

participate in their lives, might give our imaginations a robust workout

and help us become more empathetic.

Mysteries can even

help us empathize with criminals. That's ironic, in a way, because some

social science studies argue criminals are marked by an inability

to empathize. Then again, other social science studies challenge those

studies, and still other studies--but maybe we shouldn't get into all

that. Maybe we should just pick up a favorite mystery and start reading.

I bet it'll do us good.

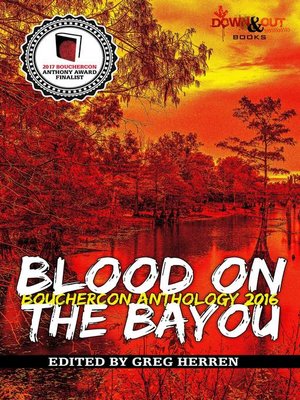

Next

week at this time, many of us will be at Bouchercon. Just briefly, I'll

mention some SleuthSayers nominated for Anthony awards. Art Taylor's

On the Road with Del and Louise,

a remarkable example of a mystery that encourages us to empathize with a

wide variety of characters, is a finalist for Best First Novel. Art

also edited

Murder under the Oaks, a finalist for Best Anthology or Collection; both Rob Lopresti and I are lucky enough to have stories in that one. And my

Fighting Chance is a finalist for Best Young Adult Novel. If you're so inclined, you can read the first chapter

here. Hope to see you in New Orleans!