31 January 2023

The Importance of Emotional Motivation in Fiction

by Barb Goffman

30 January 2023

Word salad? Dig in.

by Chris Knopf

I fell in love with words at an early

age. I don’t just mean a love of

literature, but of the individual words themselves. One strong influence was all the adventure

books from the late Victorian and early 20th century passed down

from my father and grandfather that I devoured like giant bowls of buttered

popcorn.

They were written in the style of the 19th century, which leaned toward the purple and prolix. Ornate language peppered with words you’d never see in contemporary literature, much less hear in everyday conversation. I’d look up their meaning in my brother’s exhausted Merriam-Webster’s, and catalog the definition in my tender memory.

I also used quite a number of these forgotten words and usages in my earliest writing, much to its detriment. Few high school English teachers had ever heard of Stygian darkness or a flexile snake. Or would approve of a stern expression being described at a stately countenance, or a homeless guy on a street corner as a mendicant. But I did.

By the way, Victorian writers often interchanged “he exclaimed” with “he ejaculated.” Even as a junior writer I knew this was an anachronistic usage best avoided.

It wasn’t until I started reading

Hemingway, that god of succinct and efficient prose, that it dawned on me: big words – worse, obsolete words – make you

sound ridiculous and pretentious. This

was somewhat countered by James Joyce, who used every word in the language, and

conjured a few neologisms of his own, but did so with such poetical brilliance

that few griped about it. Not being

Joyce, I’d simply choose to pop in a bit of obscure vocabulary every once in a

while, and wait for the editors to circle it and write, “Huh?”

I’m not the first logophile, by any

means. William Buckley famously

confounded even hyper-educated PBS viewers with the sweep of his lexicographical

panache, often insulting his guests on Firing Line without a breath of reproach, since they’d have no idea what he just called them. Shakespeare is not only the Greatest English

Writer of All Time, his vocabulary is still thought to be the largest ever

recorded. And this without Google, or

dictionaries for that matter. But I’d

also commend modern writers such as Anthony Burgess, Tom Wolfe, Joyce Carol

Oates and Christopher Hitchens as no slouches in this department.

English has been described as a

whoreish language, in that it will copulate and reproduce with every other

language on earth without shame or regret.

That’s how we ended up with so many words, so many derivations, such

richness of expression. The French, of

all people, find this tendency unseemly, and try to block outside influence, which

is one reason why English is now the closest thing we have to a common world

tongue. The new Lingua Franca.

With such an enormous and diverse

palette to choose from, it takes discipline to select words that get the immediate

job done, though I can’t resist the occasion when a big, fat, juicy splotch of verbal

obscurity seems like just the right thing.

It may not always serve the purpose of my writing, but it’s fun.

Even ineluctable.

29 January 2023

Simple Mathematics

by R.T. Lawton

Mathematics is derived from two Greek words:

'Manthanein' meaning 'learning' and 'techne' meaning 'an art' or 'technique.'

Mathematics simply means to learn or study or gain knowledge. The theories and concepts given in mathematics help us understand and solve various types of problems in academic as well as in real life situations. Mathematics is a subject of logic.

So, now let's see how we can use mathematics to reduce real life undercover situations to simple equations.

Our first equation would look like this: IM + T = PD

IM stands for Informant Motivation which has several subsets

Revenge: the informant wants revenge on a criminal because of a real or imagined hurt

Money: The informant wants or needs money and therefore is willing to work for law enforcement on a limited basis

Leniency: the informant has a case against him and is cooperating to get less or no time on his sentence

Rival: the informant wants to cripple or get rid of a rival criminal/criminal organization

Public Minded: the informant doesn't want this particular criminal/criminal organization in his neighborhood

Profession: yes, there are informants who travel from city to city and work this as their profession

T stands for Trust. If the informant is in good standing with the criminal/criminal organization, then more than likely when the informant introduces the undercover agent to the criminal/criminal organization, they will accept the undercover agent.

NOTE: T does not mean that the undercover agent or agency should blindly trust the informant. Think about it. The informant is scamming the people he is introducing the undercover agent to, so sooner or later he may start scamming the agent and enticing him into a bad situation or even breaking the law in some fashion. After all, a criminal has no better currency for getting out of a jam than to offer up a corrupt cop.

The Russians have an old proverb, "trust, but verify."

As we Americans have recently applied this saying to China, "distrust and verify."

PD represents our Potential Defendant. Now, put it all together. A motivated informant (IM) who is trusted (T) means that an undercover agent should be able to acquire whatever evidence or contraband goods are needed to end up with the arrest of a potential defendant (PD).

Our second equation would look like this: O + G =BB

O represents opportunity

G is the target's greed

BB means buy bust

Here's an example of Opportunity. A hashish dealer travels to the Middle East, scores several blocks of blond Lebanese hashish, conceals the hashish in the walls of three smuggler's trunks, ships one trunk to a friend's house in Miami and the other two trunks to his unsuspecting mother in Sioux City, Iowa. Unfortunately for him, Customs has drilled a hole in one wall of each trunk and retrieved core samples of hashish.

The one trunk is delivered to the friend's house in Florida, the recipients open the trunk with glee, but soon spy the the drilled hole and flee out the back door. They are as they say, "in the wind."

The other two trunks are delivered to mom's house in Sioux City. Dear old Mom is soon reading a search warrant and wondering what the heck is going on. Law enforcement remove the trunks and recover two letters from prospective buyers of the hashish. These two letters, containing the prospective buyer's telephone numbers, provide the opportunity.

Now comes the Greed. I use the first telephone number to call the wannabe buyer in Omaha. I explain that the big dealer is currently taking care of business in Florida and therefore he has asked me to make some calls to deliver the hash from the other two trunks. How much would he like to purchase? We arrange for me to call him in the near future to set up a time and place for the transfer of hashish and money. Now remember, this is the first time this guy has met me and that's over the phone. Greed has blinded him from taking precautions. He gets a warning call before I call him back and he subsequently joins the In The Wind Program. Lucky him.

I call the second number, located in Des Moines, not part of our Resident Office territory. This future arrestee arranges to meet me in in a tavern. He describes himself, sets the time and place and says he will be sitting at the bar. All is agreed, but since our agency has temporarily run out of travel funds, I contact an agent in our Des Moines office and provide him with the details. He and his partner only have one block of black hashish available to them from old evidence, so they wrap up some slender telephone books to make it look like they have more. The agent meets the future arrestee in the bar. They talk. Future arrestee mentions that the agent's voice sounds different than on the phone. That should have been his first clue, but greed intervened.

They go out to the parking lot. Agent takes the block of real hashish to the future arrestee's vehicle. Future arrestee's partner goes to the government car where 2nd agent waits with the rest of the hashish blocks (wrapped up phone books). After future arrestee sees the real hashish sample block then the exchange will take place. Future arrestee mentions the hashish is black instead of blond. That should have been his second clue. Agent makes up story. Once again, greed overrules good sense. The idiot produces the money, and since we can't let the hashish walk, the agents bust them, seize their money and vehicle and return the hashish to old evidence. Thus, Opportunity (on our part) plus Greed (on their part) equals a Buy Bust.

These simple equations can also be applied to plots for crime, mystery or spy stories, merely change the circumstances.

Enjoy.

28 January 2023

We, The Jury

It's Derringer time, and that's prompted me to think about the whole literary jury process. I've been on several, and this guest post below, by my good friend and author Jayne Barnard, really speaks to me. How about you? Have you ever been on a literary jury? Please tell us your experience in the comments below.

We, the Jury...

by J.E. Barnard

When a crime writer hears the 'J' word, they can be forgiven for thinking Twelve Angry Men, A Jury of Her Peers, or any book, movie, or news article about a trial. Maybe our minds veer to Grisham novels about juries or the Richard Jury mysteries by Martha Grimes. Rarely do we consider the other kind of jury: the one that decides on a writers' award. Whether it's the National Book award, the Giller Prize, the Governor General's Award, the CBC or Writers Trust, or--particular favourites of crime writers--the Edgars, Agathas, Daggers. Derringers, Theakston's Old Peculiar, and Canada's own Crime-writing Awards of Excellence (formerly the Arthur Ellis Awards,) there's a jury behind it.

After two decades of serving on writers' juries in the Canada and the USA, for fiction and non-fiction, children and adults, short fiction and long, even for plays and scripts, I've got some thoughts to share about what makes a good juror and why writers would, indeed should, try jury work at least once in their literary career.

Who sits on a writers' award jury?

The fact is, juries are made up mainly of readers and writers like you. Award-winning authors, multi-series authors, one-book authors, true crime authors, short story authors, journalists, bloggers, reviewers. Other seats are filled by those working in the publishing industry, or in libraries, or those with subject area experience like lawyers, prosecutors, criminologists, pathologists, cops. But mainly writers and readers.

What makes a good crime writing juror?

1. Someone who loves crime writing. Writing it, reading it, listening to it, watching it.

That juror represents all readers of that crime category. Ideally, they're aware of what's hot in crime writing and tropes that are past their prime. The good juror accepts that, as much as they personally may love the Golden Age detective authors like Agatha Christie and Dashell Hammett, the genre has moved on, and the awards moved on with it. The good juror knows that even though they personally love cozy cat mysteries with recipes or serial killer POV scenes in alternating gory chapters, the genre is far wider than both and they must evaluate all entries in their category not on what they personally prefer but on how well the author has executed a work according to its place on the crime writing spectrum.

2. Collaboration. This essential qualification is too often left unstated. It's rare that a single book or story rises to the top of every jury member's list. Any category may include several eminently worthy candidates for the top slot. Jurors need to communicate their shortlist selections clearly to fellow jurors and be able to defend those choices with calm, clear language, while respecting other jurors' alternative perspectives. Only together can jurors develop a short list that reflects the breadth of excellence in that category of writing.

Other qualifications: your writing credentials and your relevant life experience. A working children's librarian or elementary school teacher is better placed to evaluate a Children's and Young Adult category than, say, a retired criminology professor who taught adults and has no regular contact with child and adolescent readers. It's not that the latter couldn't evaluate the writing and the structure, but that they're unfamiliar with what readers in that category are currently consuming and what those readers value in a book or story.

What other qualities does a good juror bring?

Ideally, they're familiar with:

- the award's writing language (in Canada, so far, that means English or French) including a solid grasp of grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

- structural issues of storytelling: plotting, pacing, tension.

- elements of a strong opening and a powerful ending.

Good jurors understand enough about characters and their arcs to tell whether they're introduced or developed poorly or well, and can explain those thoughts to their fellow jurors during the consultation process (and to the author if their jury is one that offers comments/feedback.)

Non-fiction jurors ideally have a grasp of language and storytelling as well as some subject-area expertise.

One reason why juries traditionally have three or more members is to balance overall strengths. A strong writer with two subject experts, or two writers with a lone subject expert, can turn in the strongest possible shortlist if they respect the knowledge and skills each member brings to the reading and discussion process.

Why serve on a jury?

1. To give back to the community of writers that breaks trail, nurtures your skills, and has built the publishing industry and awards processes you already are or hope soon to be competing in.

2. As a master class in what makes some stories, articles or books work better (and win awards) than others.

Trust me on the second one: jury work can revolutionize your writing practice. There are few more concentrated ways to figure out what makes a good first page than by reading twenty or more of them in quick succession to see which ones hold your attention and figure out what makes them stand out. Read twenty opening chapters and you'll have a clearer idea what kind of character introductions, settings, or situations work best - or utterly fail - to pull you into stories you might not otherwise read. Look at twenty endings and some will have a resonance you can feel to your bones while others will be just okay. Take those new or more in-depth understandings and apply them to your own writing, and your odds of seeing your work on an awards shortlist can increase exponentially.

I hope the next time a crime writing award puts out a public or selective call for award jurors, you'll take a moment to consider whether you have some skills, dedication, and desire to learn and to serve. And then apply.

27 January 2023

Good Hair Styles

Still getting the occasional email criticizing me about my December 16, 2022, article in "Hair Styles" article in SleuthSayers, so I thought I'd give equal time to some pretty cool hairstyles of movie stars from the era.

26 January 2023

How the Law Really Works

by Eve Fisher

I'm getting pretty tired of memes and op-eds that are shocked, shocked, shocked! about searches and arrests and even convictions, so I thought I'd discuss how things happen in the real world of criminal justice. And I'm going to use plain, simple language, because there too many people running around who have bought a whole lot of legal BS.

(2) If you try to sell illegal drugs, and the cops bust you, you're still guilty even if what you brought to sell was actually lawn clippings in a baggie.

(3) If you try to hire a 13 year old for sex, even if "she" turns out to be a 46 year old portly male detective, you are still guilty of trying to buy a minor for sex.

(4) If you try to sell a 13 year old for sex, even if you have no 13 year old in the stable, and were just trying to scam the purchaser, you are still guilty of pimping, as well as scamming.

(5) If you offer to kill someone for hire, and then pocket the money but don't do it, you're still going to be charged with conspiracy to commit murder.

(6) If you're conspiring with people to kidnap / murder someone or some group of people (such as the ones who conspired to kidnap and execute Michigan Governor Whitmer, or the group in Kansas (HERE) that was going to blow up a Somali community), and an informer has infiltrated your group, and the FBI (or other law enforcement) arrest you before you actually commit the crime - well, there's a reason conspiracy is a crime, and you're gonna find out the hard way.

Basically, it doesn't matter if you didn't get or didn't give what was offered - what matters is that you intended to get or give what was offered.

Cathy the Catburglar comes to Paul's Pawnshop in New York City with a diamond ring valued at $10,000. "Wow, that's a beautiful ring," Paul says to Cathy. "Where'd you get it?"

"Duh. I stole it. I'm a cat burglar. It's right in my name."

"Right," says Paul. "But where did you steal it from?"

"I'd rather not say," Cathy replies, "but don't worry. I didn't steal it around here. Let's just say that an heiress in California will find that her hand feels a little lighter than it used to."

"Gotcha," Paul replies. "I'll give you six grand for the ring." They haggle and eventually settle on a price of $7500.

Paul has committed a federal crime of receiving goods valued at over $5,000 that he knows to be stolen and that crossed state lines. He has also committed third-degree possession of stolen property under New York law. The fact that Paul didn't steal the ring himself or play a role in Cathy's crime does not shield Paul in any way. (DORF)

Another one is the "hearsay doesn't count" defense:

(1) Pretty much every single Mafia and other crime boss who's been indicted, tried, and convicted has been put there by the witness of other criminals - usually their [former] employees. Except for those who got caught cheating on their taxes. Sometimes them, too.

"People commit murders largely in the heat of passion, under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or because they are mentally ill, giving little or no thought to the possible consequences of their acts. The few murderers who plan their crimes beforehand -- for example, professional executioners -- intend and expect to avoid punishment altogether by not getting caught. Some self-destructive individuals may even hope they will be caught and executed." (ACLU)

Or, as someone said recently on Facebook in one of the greatest memes I've ever seen, which said simply, "We already know what caused the shootings: Hate/Fear/Rage"

But executions are always a popular idea. A commenter on Facebook wrote me that the best way to stop crime and lower prison populations is to execute all violent criminals and drug dealers and - well, it was a long list. I instantly thought of Larry Niven's short story, "The Jigsaw Man" (in the original Dangerous Visions anthology that I've referred to a few times).

Synopsis from Wikipedia, "In the future, criminals convicted of capital offenses are forced to donate all of their organs to medicine, so that their body parts can be used to save lives and thus repay society for their crimes. However, high demand for organs has inspired lawmakers to lower the bar for execution further and further over time.

The protagonist of the story, certain that he will be convicted of a capital crime, but feeling that the punishment is unfair, escapes from prison and decides to do something really worth dying for. He vandalizes the organ harvesting facility, destroying a large amount of equipment and harvested organs, but when he is recaptured and brought to trial, this crime does not even appear on the charge sheet, as the prosecution is already confident of securing a conviction on his original offense: repeated traffic violations."

So be careful what you advocate for. I've seen how you drive.

25 January 2023

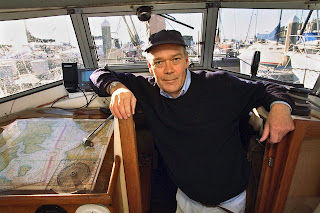

Jonathan Raban

Jonathan

Raban died last week. He was eighty –

not a bad run. He didn’t hit my radar

until Old Glory, but certainly other

people knew who he was already. He

resisted being called a travel writer; like Bruce Chatwin, he was somewhat sui generis, a writer of moods, and

weather, sudden storms and inner barometrics.

He wasn’t always the easiest guy to get along with, it’s said, but he

gave as good as he got.

Old Glory is

about a boat trip down the

This

bemused self-deprecation is of course a fiction, or a convenience, it wears out

its welcome – it’s maybe a Brit thing, too, that affectation – and Raban

discards it, later on. By the time of Passage to Juneau, eighteen years on, the

voice is no longer passive, and it’s fairly caustic, a burden of greater

self-awareness.

Somewhere

in the middle, he wrote the novel Foreign

Land and a memoir, Coasting,

which are back-to-back, and hold a mirror up to one another. Both books are about a sailing trip around

the coastline of

He called the lure of the open road (or the open water) a path to “escape, freedom, and solitude.” He seems to have had a less than joyful childhood, and his taking leave of things is a constant, one restless eye always tipped toward the horizon. I wish him, at the end, safe harbor.

24 January 2023

Boys Two Tax

When I was ten years old, my dad brought home a conversion kit for my bicycle. He installed a banana seat and high-rise butterfly handlebars so that I could ride a Sting-Ray, just like the cool kids.

Alas, Dad could change the bike to cool, but the rider remained unreformed.

I was reminded of my bicycle’s conversion in a rather roundabout Proustian moment the other day. Sitting at my desk in the courthouse basement reviewing cases, I was presented with an officer’s affidavit.

He pulled over a pickup on a routine traffic stop. As he approached the vehicle in the bed, he spotted a Cadillac converter.

Having some familiarity with our local crime trends, I knew that the officer had likely spied a stolen catalytic converter. The voice-to-text, called-in report had changed the stolen object. If one says the words out loud and mumbles just a smidge, it is easy to hear how the substitution occurred.

In the moment, however, my imagination ran wild. I envisioned Hyundai Elantras or Chevy Sparks sprouting tailfins and hood ornaments, stretching out before my eyes until they became El Dorados. The Cadillac converter rolling around in the back of this defendant's pickup brought the transformation from an entry-level motor vehicle to a classic American roadster.

That sort of thing happens when you spend too much time alone in the basement.

Cadillac converter is a petite-typo, a small error, easily understood in a world of dictated reports and auto-corrections. January 2023 has provided several examples already. Perhaps the new year brought software upgrades to the local departments, and the bugs are still being worked out. None of these are significant, but each has successfully taken me away, if briefly, from the subject of the offense to consider the alternative reality posed by the language on the page.

Consider where your mind goes with the following actual examples:

“John Smith was arrested leaving the Budget Sweets.”

Envision the Willy Wonka-esque crime implied by the sentence. Readers might quickly fix this one and picture the malefactor sneaking away from the Budget Suites, a low-rent motel just off the freeway. Lots of offenses occur there. But a discount candy store as a crime scene? Maybe Hershey, Pennsylvania, has that problem, but it is unheard of here in Fort Worth.

Or perhaps this example:

“I apprehended John Smith before he was able to flea.”

If true, legal pundits will be forced to consider the definition of the verb, to flea. Can a pest infestation be a weapon? What constitutes a swarm? Fortunately, my colleagues and I were spared all that scholasticism. Smith merely hoped to run away. He was arrested by the police and not by animal control.

If the workload is heavy and I’m blessed with a smidge of discipline, the above auto-corrections rarely slow me down. They are momentary distractions, encouraging flights of imagination in the free moments. Occasionally, however, the auto-corrections indeed prove disruptive.

The other day, for example, Officer Lawful met Smith and Jones regarding a dispute. The police report described Officer Lawful comforting Smith after hearing his statements. I regularly read examples of officers offering succor to distressed individuals, so the emotional support did not seem out of place. Smith’s version of events changed while being comforted, and Officer Lawful subsequently arrested him.

In a world absorbed only through the printed page, the electronic shifting from confronted to comforted changed my perception of who the arrestee would be. Like a bad plot twist, it took me out of the story, and not in a good way.

As I think about my writing for 2023, I hope that exposure to these errors reminds me of some basic lessons. When I'm writing, the words matter. Seeing silly examples of word choice should prompt me to take extra care with my language decisions in the stories I'm trying to create. At least, I hope it does. The more important lesson for me is the reminder to carefully proofread my pages. And then reread them before hitting "send." I regularly see how a garbled or inattentive word changes my reading of a police report.

My apologies to Michael, Barb, and my other editors for the typos and word choices they’ve comforted.

Until next time.

23 January 2023

Dr. Watson Had How Many Wives?

DR. WATSON HAD HOW MANY WIVES?

by Michael Mallory

How many wives did Dr. John H. Watson, of Sherlock Holmes fame, actually have? The fact that so many people even care about this is a trait of those devoted Sherlockians who like to purport that Holmes and Watson were real people, not iconic fictional characters. That is the “grand game” as put forth by today’s Baker Street Irregulars (BSI), an organization of devoted Holmesophiles who pretend that Watson actually participated in and recorded the adventures of his singular friend, and that this Arthur Conan Doyle chap was simply his literary agent.

My personal opinion of this mindset is that it rather disrespects a major Victorian author, but for these purposes, that is neither here nor there (other than the acknowledgement that by humbugging the grand game, I will never be invited to join the BSI). My purpose is to speak about how many trips the good Dr. Watson made to the altar and why it is even in question.

For nearly 30 years now I have been turning out stories, novels, and even one full-length play featuring Amelia Pettigrew Watson, whom I call “the Second Mrs. Watson.” There is a sound reason for this, to my way of thinking, but many Sherlockians disagree. I have heard theories that Watson was married a total of six times, and once encountered a Sherlockian who claimed to have evidence that the real number of wives was 13! Since this would paint Watson as either the second coming of Bluebeard or the first coming of Mickey Rooney, I did not take him very seriously. For most faithful Sherlockians, however, the number is three, though we only have details of one of them.

Watson’s only indisputably-documented wife was Mary Morstan, the heroine of the novel The Sign of the Four. Mary is mentioned in another half-dozen short stories, and while her union with Watson appeared to be very happy, it was short; she died “off-stage” during Holmes’s “Great Hiatus,” his multi-year disappearance after presumably being killed by Professor Moriarty.

The only other mention of Watson remarrying comes from the story “The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier,” which was published in The Strand Magazine in 1926 and collected in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes the next year. In it, Holmes himself writes: “I find from my notebook that it was in January, 1903, just after the conclusion of the Boer War, that I had my visit from Mr. James M. Dodd, a big, fresh, sunburned, upstanding Briton. The good Watson had at that time deserted me for a wife, the only selfish action which I can recall in our association.” One of only two short stories narrated by Holmes himself, “Blanched Soldier” reveals a surprisingly vulnerable detective who, based on the above comment, is hurt and angry over Watson’s abdication for a woman. It also generated one of the biggest mysteries within the Holmesian canon, since this mystery woman was not identified and was never heard from again.

In 1992 I began playing around with the idea of writing a Holmes and Watson pastiche told from a woman’s point of view. Using Irene Adler seemed too obvious, while Mary Watson never seemed to engender such a feeling of replacement in Holmes’s life. Then I remembered the “second,” unknown Mrs. Watson, and from that single reference to her developed Amelia Watson. She is not only Watson’s devoted, slightly younger wife, but I present her as something of a foil to Sherlock, particularly if she believes Holmes is using her husband.

I remain grateful that faithful Sherlockians have enjoyed her adventures, particularly since I have at times treated the legend rather playfully through her POV, the chanciest conceit being that maybe Watson was a better writer than Holmes was an infallible detective, and he fixes his friend’s mistakes in print. The only point of contention I’ve encountered from the faithful is in presenting Amelia as Watson’s second wife instead of the third. But if Mary Morstan was Watson’s second wife, not his first, and Amelia was his third, not his second, who was the first? The answer to that can be found only outside the canon of 56 short stories and four novels written by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Sometime in the late 1940s, author and Sherlockian John Dickson Carr was granted permission to look through Conan Doyle’s private papers in preparation for writing his biography. One thing Carr discovered shocked him. Around 1889, in between the publication of the first Sherlock Holmes adventure A Study in Scarlet (1887) and the second, The Sign of Four (1890), Conan Doyle wrote a three-act play titled Angels of Darkness, which dramatized the American scenes from A Study in Scarlet. Holmes was nowhere to be found in it; instead Watson was the main character. By the play’s end the good doctor was headed toward the altar with a woman named Lucy Ferrier, who was a character from the flashback section of the source novel.

Carr’s dilemma was that this previously unknown work, which Conan Doyle never intended to see the light of day, upended the “facts” of Watson’s life. “Those who have suspected Watson of black perfidy in his relations with women will find their worst suspicions justified,” Carr wrote of his discovery. “Either he had a wife before he married Mary Morstan, or else he heartlessly jilted the poor girl whom he holds in his arms as the curtain falls on Angels in [sic] Darkness.”

Making the problem even murkier for grand gamers, Lucy Ferrier could not be the first Mrs. Watson since The Sign of the Four has her dying in Utah sometime in the 1860s, when Watson would have still been a schoolboy. In light of this stunning discovery, Carr’s felt he had only one option: keep it to himself. He wrote that revealing the woman’s identity would “would upset the whole saga, and pose a problem which the keenest deductive wits of the Baker Street Irregulars could not unravel.” One man, however, accepted the Gordian challenge.

William S. Baring-Gould (1913-1967) was not only the leading Sherlockian of his time; he became something of the St. Paul of Sherlockania, a writer who fashioned the outer-canonical Gospel of Baker Street which is accepted by the faithful to this day. Realizing that John Dickson Carr was right in his assessment that the Watson-Ferrier match would turn the entire saga on its head, he did what all good authors do: he made things up. Baring-Gould put forth the notion that Watson had traveled to San Francisco in the early 1880s and there met a woman whom he subsequently married, but it was not Lucy Ferrier. It was someone named Constance Adams.

Who?

The first mention of Constance Adams appears in Baring-Gould’s 1962 “biography” of Holmes titled Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, and although she exists nowhere in the writings of Conan Doyle ─ not even in Angels of Darkness ─ having the Baring-Gould imprimatur meant that her existence was taken as a given by many.

Even so, I maintain that Mary was Mrs. Watson #1 and Amelia is #2, and for a very simple reason: in crafting Amelia and John’s adventures, I rely on the Holmesian canon rather than later interpolations by others. The same is true when I write a Holmes pastiche that does not feature Amelia. While I take playful liberties here and there, the guidebook for me begins and ends with those 56 stories and four novels, occasional contradictions and all. (For the record, I also ignore Dorothy L. Sayers’s speculation that the “H” in John H. Watson’s name stood for “Hamish,” which is now acknowledged dogma.) In the Amelia universe, she is the Second Mrs. Watson (though in British editions, she is “the OTHER Mrs. Watson,” which I’ve rather come to like as well).

That said, I have not ignored Constance altogether. In a bow to the non-canonical mythology, I included her in my short story “The Adventure of the Japanese Sword,” which is set in San Francisco, and fully explains her youthful association with Watson which is misinterpreted as matrimonial.

You see, two can play the grand revisionist game.

22 January 2023

Dying Declarations II

by Leigh Lundin

II. A Hiss Before Dying

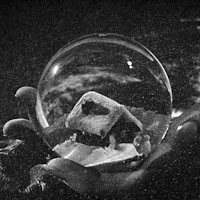

Lights down, curtain up, the famed film unreels.

Two minutes… ⏱️ … two minutes of reverent silence lapse as the camera passes under a gate bearing an encircled letter K. In the distance, a castle-like mansion beckons, a single lit window draws in the audience.

Through the glass, snow, swirling mysterious snow. When the camera pulls back, the scene reveals a snow globe cupped by an aged, dying man.

As the old man expires, the sphere rolls from his hand and shatters.

At that moment, theatre doors burst open. A piercing shaft of light slices the audience’s peripheral vision. The late-comers stumble and mumble, and their voices boom through the hushed auditorium.

“Hold this. Oh geez, I told that kid extra butter, no ice and lookie, extra ice and no butter. I’m gonna slap him silly. Hey, it’s started already. Oh, it’s that old guy, Orkin something. Scuse me. Oh crap, it’s in black and white.”

“Damn it. I can’t see. Scuse me. Scuse me.”

“Shh! Shh!”

On screen, the dying man whispers something approximating, “Яzzchoz€ßplub.”

“Whuh?”

💬

“What’d he say?”

“Don’t know.”

“Shhh!”

“He said nose rub.”

“Slow snub?”

“Or clothes scrub.”

“No, no. Hose tub.”

“That makes no sense.”

“Maybe he whispered nose blood.”

“Like nosebleed? ’Cause he’s dying?”

“I’m thinkin’ Moe’s Pub.”

“Nonsense, no Moe and no pub.”

“It’s the bar next door. I need a drink.”

“Are you all deaf? He said toe stub.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“Shhh.”

“Huh?”

“He said snow glub.”

“No way. It was a snow globe, not a glub.”

“When it rolled, it went glub-glub.”

“That’s silly.”

“Honey, would you go back to the concession stand?. I can’t eat popcorn without butter.”

“Shhh!”

“Scuse me. Scuse me. Scuse me.”

“What?”

“Turn off your phone!”

“I’m googling.”

“What’s it say?”

“Yo. Reddit says rosebud.”

“What? That makes even less sense.”

“Facebook misheard it too.”

“Scuse me. Scuse me. Okay, they gave us triple butter.”

“Two hours debate and we still don’t know.”

“I vote to close-caption theatre subtitles.”

“That concessions kid forgot salt.”

“Shhh.”

“#@%£∂!”

👀

“Hey, look. Something’s painted on… on… on that burning thing. What is that?”

“A bedstead?”

“A bobsled?”

“Bob’s sled? Who’s Bob?”

“Shhh!”

“What does it mean?”

“I want a refund.”

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a show stub.”

“That’s the ticket.”

“Shhh!”

Wait! There’s more. ☞

21 January 2023

A Cold Case

by John Floyd

Those of you who know me well know I'm not fond of winter weather. My friends in northern climes often say, to irritate me, "I love the changing of the seasons." Well, I love it too, when it changes to spring. I get cold just writing about wintertime, which is something I did for my latest story in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.

"Going the Distance" (Jan/Feb 2023 issue) isn't a Christmas story any more than Die Hard is a Christmas movie, but it happens during that time of the year, and during a freak snowstorm in the Deep South. That's also the home of the three characters in my Ray Douglas mystery series--former lawyer Jennifer Parker, Deputy Cheryl Grubbs, and Sheriff Raymond Kirk Douglas (his father was a movie fan). In this, the seventh installment of my lighthearted series set in the fictional Mississippi town of Pinewood, Ray and his parters in crime(solving) are investigating what could be the attempted murder of a mutual friend. As usual in these stories, my female characters are smarter than the males (I like for my fiction to reflect real life), but the unusual thing is the frigid weather, which complicates everything. Southerners often don't do well in low temperatures, and we especially aren't good at dealing with snow. We don't know how to walk in it or drive in it, and, as I heard someone say the other day, it tends to make shoppers get into fistfights at the Piggly Wiggly.

As it turned out, I had a good time writing this story, because it used a familiar setting and it used characters I've come to know and understand. Best of all, it involved something I've started doing in some of these Sheriff Douglas installments: I try to include several different mysteries in the same story--or at least a lot of different sets of clues that could lead to the solution. The first of the good sheriff's adventures, "Trail's End," uses only one main mystery that the reader can try to solve before the protagonists do, but the second, "Scavenger Hunt," has three separate puzzles in the story. The next three installments, "Quarterback Sneak," "The Daisy Nelson Case," and "Friends and Neighbors," have one mystery each; "The Dollhouse" has two; "Going the Distance" has one, but with many different clues; and the eighth installment, "The POD Squad"--which has been accepted at AHMM but hasn't yet been published--again has three completely separate mysteries in one story. I hope that kind of plot complication makes the story more enjoyable to read; I know it makes it more fun to write. A quick note: "The Daisy Nelson Case" is the only story in this series that has appeared in a market other than AHMM. It was published in Down & Out: The Magazine in December 2020.

This apparent reluctance of mine to write tales set in cold weather is nothing new: I can think of only a dozen or so of my stories that took place during the winter months. One was in Strand Magazine, one in The Saturday Evening Post, several in Woman's World, two in Black Cat Mystery Magazine, several in anthologies, etc.--but the percentage is still small. All writers have quirks, and I guess that's one of mine. I suppose I feel more comfortable and more believable making my characters sweat instead of shiver, unless the shivers are a result of the plot.

The same thing goes for locations. I've never done a tally, but I suspect at least three-fourths of my short stories are set in the American South, which I consider to be Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Texas and Virginia are questionable--probably Florida too, for that matter--but I doubt I'd get many arguments about the rest. I've traveled a lot in my years with IBM and the Air Force, and I'm comfortable writing about faraway locations, but I feel absolutely confident writing about my own part of the country, and about characters named Bubba and Patty Sue and Nate and Billy Ray. I went to school with those folks.

How about you? Do those of you who are story-or-novel writers prefer to create stories about things familiar to you or do you enjoy the challenge of setting your fiction elsewhere, or even in different time periods? What do you think are the pluses and minuses of both?

As for me, I'll probably continue spinning tales mostly about my own green and humid corner of the world. I know its people, its towns, its history, its problems--and its weather. Besides, writing about things near my own Zip Code usually means I don't have to do as much research, or go places that require gloves and overcoats.

Matter of fact, I think I'll go adjust the thermostat.

Have a good two weeks.

20 January 2023

Only Immortal For A Limited Time

by Jim Winter

|

| Source: jeffbeck.com |

I'm writing this the day after the great Jeff Beck passed away at the age of 78. Together with the other two Yardbirds legends, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, Beck played a huge role in expanding my musical palate. Every kid of a certain age came up on Clapton's blues and country influenced rock, though it's his work with Cream and shortly thereafter that caught the attention of us metal heads. Then there's the lick master, Pagey. If you were a Gen X male in the Midwest, Led Zeppelin dominated your playlists. In fact, I often joke that, in 1989, I had a mullet, all Zeppelin on cassette, and a Camaro. No photographic evidence exists of the mullet. The Camaro died of benign neglect. But Zeppelin when straight to CD as soon as that format became available to me.

At the center was Beck. With Ronnie Wood (later of the Rolling Stones) and Rod Stewart, he formed a sort of proto-Zeppelin.But alas, it was Page and John Paul Jones and, eventually, Bonham and Plant, that went for the heavier sound. Beck turned to his true love, jazz, to reinvent rock and roll, with a whole lotta Miles Davis as inspiration.

And now he's gone. So is Bowie. And Neil Peart. And Charlie Watts. Emerson and Lake, leaving only Palmer. Mick Mars of Motley Crue, who thrilled many of my high school classmates (I was a Deep Purple, classic metal kinda guy. No Ozzy for me. Gimme original Sabbath, who sounded like a garage band. A really good garage band.) had to retire because his joints are freezing up. Chris Squire, the sorcerer on bass, and his partner, drummer Alan White, are gone. I mention this to my brother every time we lose another legend. And he always says the same thing.

"We're getting to the age where we're losing our heroes."

In a way, that's sad. I like to point out that there are still three Beatles alive. Paul and Ringo, of course, but also Pete Best, who's still working. Maybe at a less noticeable level than the two surviving Fab Four, but enough to annoy the hell out of Decca Records.

It's funny because I don't respond the same way to the deaths of other artists the way I do musicians. And I'm not a musician. I probably could have been had I gotten an instrument in my teens and practiced, practiced, practiced. Even 76-year-old Robert Fripp still practices and points at guitarists I would consider lesser talents and say, "Another reason I still need to practice." But I'm not a musician, I'm a writer.

I'm sure Stephen King's eventual demise will rattle my cage. But I did not respond to the loss of Robert B. Parker, Philip Roth, or Sue Grafton the way Tom Petty still has me in mourning over five years later. And actors? Anymore, I can't keep up with the younger ones, and the older ones I often catch myself saying, perhaps tactlessly, "He/She was still alive?" (Alan Rickman was an exception. That one hit hard.)

But musicians are a different breed. They shine brightly in the beginning, achieve a certain level of success that lets them do what they really want, then use the original glory to support their music habit well into old age. (Yes, Willie Nelson is still working in his 90s. I suspect the Stones will be the first centenarian rockers. Well, rocker. They are slowly turning into the Keith Richards Band.)

It does, however, go back to living memory. During my childhood, the echoes of World War II still rumbled loudly, even overwhelming the Cold War. Though my grandfather did not serve, he worked for GM during the war, and many classmates' parents and grandparents served in some capacity, military or civilian. Moreover, our reruns and special guests on sitcoms worked in that era. If the president wasn't a WWII vet - Nixon, Reagan (whose eyesight confined him to Hollywood), GHWB - then they served in Korea: Ford and Carter. But that generation is rapidly disappearing the way the World War I generation vanished before my thirtieth birthday. It might explain the confusion and uncertainty of today. Where do we go next?

For Gen X, especially the older Gen X, along with the youngest Boomers, we have music. Music brought rebellion and freedom in the sixties, unexpected flights of fancy and walls of sound in the seventies, complete reinvention in the eighties, and back to basics in the nineties. And now we're losing the ones who made that happen. That's our living memory. Perhaps in twenty years, reality stars will begin to pass on from something other than excess or accident. Old age, cancer, the next great plague will take them. And Millennials and Gen Z will feel it the as acutely as I still feel the loss of Tom Petty and Jeff Beck.