|

| Columbo © Universal Television |

Whodunit mysteries appear to be making a comeback on television, as evidenced by the series Elspeth and the highly touted "remake" of Matlock. But I think it is safe to say that no one would dare to try and reboot what is perhaps the best mystery series ever to appear on the tube: Columbo. (Not the most accurate, mind you, but the best.)

Even though Peter Falk was the third actor to play the rumpled, wily detective after Bert Freed on live TV in 1960 and Thomas Mitchell on stage a couple years later (the fourth actor if you count Mitchell's understudy Howard Wierum, who took over after Mitchell became ill), he is Columbo. Trying to replace him would be sheer folly, no matter what kind of stunt casting was attempted.

Lieutenant Columbo never failed to get his man (or woman), and those killers were played by some of the best actors available. Ten of them, though, proved to be ideal foils for the faux-obsequious detective. Not surprisingly a few of them made return appearances.

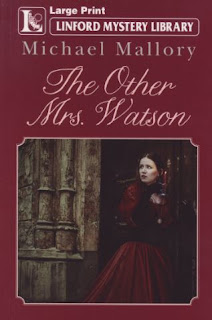

- Jack Cassidy ("Murder by the Book," "Publish or Perish," and "Now You See Him"). Glib, devilishly handsome, and always seeming to wear his ego like a fancy hat, Cassidy was the perfect Columbo murderer. In each of his guest turns he played a different character, but all three shared a common trait: they were done in by their sheer arrogance in refusing to believe they weren't the smartest person in the room. "Publish or Perish," in which Cassidy plays an unscrupulous and vindictive publisher, contains my favorite Columbo moment of all -- but only for personal reasons. In the episode, Mickey Spillane plays a best-selling author named Allen Mallory, who is murdered by Cassidy. In a typical Columbo scene, the detective is getting on the publisher's nerves by sounding him out about writing a book of his own. At one point, Peter Falk says, "Oh, I'm not a great writer like Mr. Mallory or anything…" Obviously, I always enjoy seeing that otherwise innocuous dialogue exchange.

- Dick Van Dyke ("Negative Reaction"). If you've only seen him as Rob Petrie or Bert the Chimney Sweep, or any other role that draws upon his comedic affability and essential Dick Van Dykeness, you will be shocked by his performance as one of the coldest and most calculating killers in the entire series. Sporting grey hair and a white beard, and chilling every scene with a frigid gaze, Van Dyke is barely recognizable. "Negative Reaction" also contains one of the series's greatest self-incrimination scenes.

- Robert Vaughn ("Troubled Waters" and "Last Salute to the Commodore"). Vaughn played the killer in one episode and a victim in the other, but in both he was on a boat. He makes the Top Ten list because more than any other actor, Vaughn projects immense annoyance with the seemingly oblivious detective without uttering a word. He and Falk played off of each other delightfully.

- Martin Landau ("Double Shock"). Landau did only one episode but in it he plays two distinct characters: identical twins with polarized personalities. "Double Shock" is unique in being the only episode in which, even though you see the murder being committed, you're not certain who did it, since it could have been either one of the twins. Dealing with two suspects offers Columbo one of his bigger challenges.

- Jackie Cooper (Candidate for Crime"). A child star from the early talkie era, Cooper tended to be underrated as an adult actor, but he is terrific as a gland-handing political candidate who offs his campaign manager and then tries to make it look like someone else is out to get him, someone who killed the manager by mistake. As Columbo begins to reel him in, Cooper's struggle to maintain his "Honest John" persona instead of revealing his true, nasty self is masterfully played. The final clue is a gem, too.

- Richard Kiley ("A Friend in Deed"). Columbo faces his most dangerous opponent -- his boss! Kiley gets to play a rare villainous role as a corrupt and homicidal deputy police commissioner, who murders his rich wife for both her money and freedom from her. Understanding what a threat Columbo is to him, he tries to thwart the investigation, even threatening to get the detective fired. The ending in which Columbo traps him is a little elaborate and far-fetched, but still clever.

- Ross Martin ("Suitable for Framing"). Martin channels Waldo Lydecker playing a snide, self-absorbed art critic who murders his rich uncle in an elaborate scheme to gain his art collection (the rich uncle, incidentally, who is only briefly glimpsed, is played by Robert Shayne, "Inspector Henderson" from the Superman TV series). Martin then tries to frame his rather unstable aunt, who actually did inherit the collection, because if she is in prison she cannot receive her inheritance, which will pass to him. The incriminating clue is one of the best of the entire show, as is Martin's moment of dawning panic when he realizes he's been tripped up.

- Janet Leigh ("Forgotten Lady"). An unusual Columbo episode in that we see the murder in the first twenty minutes, as per the format, but do not understand the motive until the very end. It is also the only show in which the killer appears to get away with it. The episode also demands a second viewing, just to see how skillfully Janet Leigh, as a washed-up movie star, lays down the clues to the surprise denouement without ever tipping her hand.

- Oskar Werner ("Playback"). Never has Columbo faced a more nervous opponent. Half the fun of the episode is not simply the usual clever cat-and-mouse antics and ingenious clues but wondering when Werner's character is going to finally shatter like a glass bottle.

- William Shatner ("Fade in to Murder" and "Butterfly in Shades of Grey"). Shatner was the guest killer in "Fade in to Murder," playing a popular television actor who kills to protect a damaging personal secret, and he's all right. But it was in an episode from the second run of Columbo, which started in 1989 and ran through the 90s, that he really excelled. In "Butterfly in Shades of Grey" (which doesn't seem to mean anything), Shatner plays a Rush Limbaugh-style radio talking head who kills his daughter's lover. Sporting a twinky little moustache, he makes his character nasty, overbearing, and (dare I say?) subtly vicious, so that when he finally gets his comeuppance, it is genuinely satisfying.

Many other actors left distinctive fingerprints over the Columbo saga, such as Lee Grant, Ruth Gordon, Robert Culp, and the two Patricks – McGoohan and O'Neal – but the aforementioned ten presented murder, malice, and mayhem at its entertaining best.

3.JPG)