Before retiring in 2009 I did my fair share of legal writing. But I did an even greater amount of editing. My approach to editing is a simple one to state, harder to put into practice. I told those whose work I was charged with reviewing (and revising) that they should write as though there were one thousand ways to write their piece erroneously and one thousand ways to write it correctly. If they got it right, it would be right, even if I might have chosen a different one of those thousand acceptable approaches. But if they got it wrong, well, then it was in my hands and I had free rein when I revised it.

Those of us who have written for a living -- as I did when I was editing those (uninteresting) legal briefs and memoranda -- have learned how to write through a prolonged process of trial and error. If successful, this process eventually results in the development of an ear for the language, an ability to “hear” what works on the page and what does not. But the process of getting there can be agonizing, and generally begins with the boot camp of learning (and following) a set of strict rules that are drilled into us at an early age. For many of us, at least those in my generation, those rules were probably initially encountered in

The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White.

The Elements of Style was originally written and self-published by Strunk, an English professor at Cornell, who was White’s teacher in 1919. Popularly, however, the volume has been available for 55 years, dating from 1959, the year when White, who had written a

New Yorker article praising the volume and Professor Strunk, edited and updated Strunk’s slender guide and for the first time published it for the mass market. Almost immediately the volume took off. Dorothy Parker said of it “If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second-greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of

The Elements of Style. The first-greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.”

But, as is the case with almost any “how to write” treatise

Strunk and White (as the book is often called) also has its detractors. Much of their criticism stems from the brittleness of the volume’s approach, its tendency to prescribe hard and fast rules in circumstances where guidance might be a better approach. In an article “celebrating” the 50th anniversary of

The Elements of Style, “

Fifty Years of Stupid Grammar Advice,” (

The Chronicle Review, April 17, 2009) Edinburgh English professor Geoffrey K. Pullum had very little good to say about the volume. As an example, Pullum takes issue with Strunk and White’s position on split infinitives.

The Elements of Style advises that split infinitives "should be avoided unless the writer wishes to place unusual stress on the adverb." Pullum rejects the approach, labeling it “completely wrong”:

Tucking the adverb in before the verb actually de-emphasizes the adverb, so a sentence like "The dean's statements tend to completely polarize the faculty" places the stress on polarizing the faculty. The way to stress the completeness of the polarization would be to write, "The dean's statements tend to polarize the faculty completely."

But arguably Pullum has fallen into the same “brittleness” trap for which he derides Strunk and White. In fact, as a purported universal rule, Pullum’s rule on adverb placement fares no better than does the

Strunk and White rule. All

Star Trek fans, for example, know that the word “boldly” is stronger under the

Strunk and White "exception" approach (“to boldly go where no man has gone before”) than it would be under the Pullum alternative (“to go where no man has gone before boldly”). When one approach works for the “dean’s statement” sentence but the other works for the

Star Trek opening, one can only conclude that there in fact can be no universal rule, nor universal exception.

Are there other pitfalls encountered when a writer follows black and white approaches religiously? Certainly. For example,

Strunk and White dictates that no sentence must ever begin with the word "and" or “however.” We are told to avoid “certainly” in almost all circumstances. “Factor” and “feature,” we are told, are “hackneyed words.” And the rule, as originally set forth by

Strunk and White, is that “to-day”, “to-night” and “to-morrow,” are only to be written using hyphens. There may be guidance in this, but hardly unbreakable rules.

In a 2009 article, also celebrating the 50th anniversary of

The Elements of Style the

New York Times had this to say:

The little book had big pretensions, which were not always appreciated by writers or even grammarians. Had they followed all the rules (avoid injecting fancy words, foreign languages and opinion), Thomas Wolfe, Vladmir Nabokov, William F. Buckley and Murray Kempton (a comma before “and” — or not?), to name a few successful writers, might have been shunted into very different careers.

Pullum’s article goes further. To make its point that rules of English usage cannot be hard and fast Pullum takes on the

Strunk and White rule that the phrase “none of us” requires the singular “is.” Using computerized searches of which the authors of

The Elements of Style could only have dreamt, Pullum points out that Oscar Wilde’s

The Importance of Being Earnest, Bram Stoker’s

Dracula, and Lucy Maude Montgomery’s

Anne of Avonlea consistently and and almost invariably use “none of us are.”

These examples illustrates the problem with any stark approach when it comes to setting usage rules. English simply refuses to play by those rules. It evolves. I used to work with someone who railed at anyone who spelled “supersede” with a “c”, decrying that this was the most common misspelling in the English language. But today “supercede” clears most spellcheckers just fine. And hardly anyone today (no hyphen) would hyphenate tonight or tomorrow as prescribed by

The Elements of Style.

The truth is, that while it is good to know the underlying rules when developing your writer’s ear, the rules themselves need to be taken with grains of salt. Once your ear has matured and developed it needs to be relied upon more than the rules. If the prose sounds right to an educated ear as it is written, it likely is right to the ear of the reader. This point was not lost on White, who, as anyone who has marveled at

Charlotte’s Web fully realizes, was possessed of a great writer’s ear. White in fact acknowledged that his own approach to writing was at least a bit at loggerheads with the black letter law of

The Elements of Style:

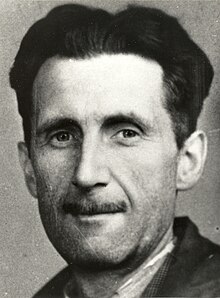

|

| E.B. White, at work at The New York Times |

I felt uneasy at posing as an expert on rhetoric, when the truth is I write by ear, . . . [but] [u]nless someone is willing to entertain notions of superiority, the English language disintegrates, just as a home disintegrates unless someone in the family sets standards of good taste, good conduct and simple justice.

To me, that says it all. The rules set forth in

The Elements of Style are foundational. Knowing them is like learning how to outline a story, or essay, in advance. Usage rules and outlining skills are tools that each of us should first master so that our writing is constructed on a solid foundation. Then, when and if we abandon the rules, or at least loosen the reins, it is with full knowledge of what we are doing.

And (I purposely begin) even then we have to be careful. In that 2009 article celebrating the 50th anniversary of the publication of

The Elements of Style, The New York Times noted that the latest edition of the book contained “ a forward by White’s stepson, Roger Angell.” Soon thereafter

The Times published a correction.

It should have been “foreword.”