Amazingly, not a single online dictionary contains a definition of the word “gullible.”

Last week many of you may have stumbled onto an online article reporting that, in an interview with Fox, Sarah Palin described at some length how Jesus celebrated Easter with his disciples. The article quotes Palin as stating that “[w]e need to return Easter back to the way it was when Jesus was still alive.” According to the article Palin explained this as follows:

When Jesus celebrated Easter with his disciples there were no Easter bunnies or egg hunts. There were no Easter sales at department stores or parades in the street. Easter was a special time of prayer and Christian activism.

I was on board for all of this. It was absurd but still barely credible. But then I came to the following quote:

Jesus would gather all the townspeople around and would listen to their stories about the meaning of Easter in their lives. Then he would teach them how to love one another, how to protest Roman abortion clinics and how to properly convert homosexuals.

Well, heck, I concluded. I had been punked. But at least I was not alone, and at least I got out early. Piers Morgan of CNN, by contrast, tweeted the story on his Twitter account as . . . err . . . “gospel.”

Hoaxes can broadly be divided into two categories. The Palin article, which appeared on the satiric website The Daily Currant, follows a pattern that is typical for the well-crafted satirical hoax: Start with a premise that is just barely credible, and then start ratcheting it up. Make each claim just a bit harder to believe and then watch to see at what stage your audience begins to jump ship. The purpose of the satirical hoax is that the reader will eventually catch on and then laugh at themselves. Or, even better, a reader like Piers Morgan might swallow the whole thing hook, line and sinker, allowing the rest of us to laugh at him. The other broad category of hoaxes are meant to be taken seriously -- they are trying to pull off the scam without ever raising suspicions. They are crafted to sneak by, leaving the reader completely unaware of the hoax that is being perpetrated.

|

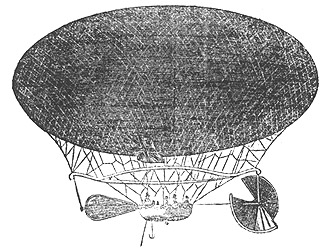

| Illustration of the triumphant balloon from Poe's article |

There have been a wealth of hoaxes of both varieties over the years, and a surprising number arise in the literary world. One of the earliest hoaxes was perpetrated by none other than Edgar Allan Poe who, in 1844 wrote a series of newspaper articles that, in great detail, recounted the first crossing of the Atlantic ocean by balloon. The story ran on the front page of the April 13, 1844 edition of The New York Sun under the following banner headline:

ASTOUNDING NEWS! BY EXPRESS VIA NORFOLK: THE ATLANTIC CROSSED IN THREE DAYS! SIGNAL TRIUMPH OF MR. MONCK MASON'S FLYING MACHINE!!! Arrival at Sullivan's Island, near Charlestown, S. C., of Mr. Mason, Mr. Robert Holland, Mr. Henson, Mr. Harrison Ainsworth, and four others, in the STEERING BALLOON "VICTORIA," AFTER A PASSAGE OF SEVENTY-FIVE HOURS FROM LAND TO LAND. FULL PARTICULARS OF THE VOYAGE!!!

The story, however, was an utter fabrication on Poe’s part. It is still debated why Poe wrote the ruse, particularly since it could not be sustained for more than a few days at best before it would unravel under close public inspection. But, at a time when financial matters might have had a more preeminent place at the publishing table, the story sold a record number of copies. And the retraction, published on April 14, did almost as well.

Poe was not alone here. In a December 28, 1917 New York Evening Mail article entitled “A Neglected Anniversary” H.L. Mencken offered a detailed, and completely fictitious, history of the bathtub. The article is still, at times, relied upon as authority for the (erroneous) propositions that the bathtub was first invented in 1842 and was first used in the White House by Millard Fillmore. Over thirty years later Mencken still marveled over the lasting power of his hoax:

The success of this idle hoax, done in time of war, when more serious writing was impossible, vastly astonished me. It was taken gravely by a great many other newspapers, and presently made its way into medical literature and into standard reference books. It had, of course, no truth in it whatsoever, and I more than once confessed publicly that it was only a jocosity ... Scarcely a month goes by that I do not find the substance of it reprinted, not as foolishness but as fact, and not only in newspapers but in official documents and other works of the highest pretensions.

There have also been numerous examples of literary hoaxes that were never meant to be found out -- usually scams concocted with a dollar sign at the hoped-for finish line. Who can forget The Hitler Diaries, which had their 15 minutes of fame in 1983 when the German magazine Stern paid nine million marks to publish thirty eight volumes of the “autobiography” of Adolf Hitler that turned out to be crude forgeries riddled with historical inaccuracies and copied in large respect from other volumes? And who can forget Clifford Irving’s attempt in the early 1970s to fake an “authorized” biography of Howard Hughes, based on interviews between Irving and Hughes that never happened?

There have also been numerous examples of literary hoaxes that were never meant to be found out -- usually scams concocted with a dollar sign at the hoped-for finish line. Who can forget The Hitler Diaries, which had their 15 minutes of fame in 1983 when the German magazine Stern paid nine million marks to publish thirty eight volumes of the “autobiography” of Adolf Hitler that turned out to be crude forgeries riddled with historical inaccuracies and copied in large respect from other volumes? And who can forget Clifford Irving’s attempt in the early 1970s to fake an “authorized” biography of Howard Hughes, based on interviews between Irving and Hughes that never happened?

To really savor this hoax a little background is necessary. As any writer knows, there are many publishers out there, some legitimate, some less so. Around fifteen years ago a new one, Publish America, entered the fray Since its beginning Publish America has gone to great lengths arguing that it is not a vanity press. But many authors have nonetheless complained that Publish America operates by publishing any manuscript it receives and then making its profit by enticing the authors to buy large quantities of very expensive volumes of their own work so that the authors can sell these to friends, relatives or (perhaps) friendly bookstores. Throughout all of this Publish America has claimed that it is a legitimate publishing house that only publishes works that it has reviewed and deemed meritorious. It goes so far as to suggest that it has an 80% rejection rate for manuscripts. It’s website proudly makes the following claim to aspiring writers:

If indeed you have been dreaming of getting published, and you want us to review your work, please fill out the form below and let us know who you are and what you have written. Your manuscript will be reviewed by our Acquisitions staff, who will determine whether your work has what this book publisher is looking for.

Sometimes you need to be careful when you throw down the gauntlet. A number of writers from the Science Fiction Writers of America, under the general direction of James D. MacDonald, the author of many successful science fiction novels and a long-standing opponent of vanity presses, decided to put Publish America to the test. He gathered a group of fellow SciFi writers and they collectively agreed to write a book. But not just any book. The writers committed to do all they could to produce the worst book imaginable.

Following a general outline written by MacDonald each writer was assigned one chapter and asked to write it as horribly as possible. None of these authors was privy to the complete outline, and no one of them knew what the chapters other than their own were to contain. Here is a sample of the prose they produced, taken from the book’s website:

Richard didn't have as sweet a personality as Andrew but then few men did but he was very well-built. He had the shoulders of a water buffalo and the waist of a ferret. He was reddened by his many sporting activities which he managed to keep up within addition to his busy job as a stock broker, and that reminded Irene of safari hunters and virile construction workers which contracted quite sexily to his suit-and-tie demeanor. Irene was considering coming onto him but he was older than Henry was when he died even though he hadn't died of natural causes but he was dead and Richard would die too someday. . . .

Not only is the book consistently clumsy, a clod of words riddled with grammatical and syntax errors, its internal structure is designed to strain credulity well beyond the breaking point. Chapters 13 and 15, written by two different authors, cover identical events in the narrative. Chapter 21 is missing, while chapters 4 and 17 are identical, word for word. Chapter 34 is “written” by computer story generation software that constructs the narrative from a word analysis of previous chapters. Toward the end of the book one chapter reveals that all that preceded was in fact a dream, but then subsequent chapters continue the narrative (such as it is) with no reference to that revelation. The genders of key characters periodically switch and then switch back. The book is, in a word, a mess, contrived to be the worst novel ever written. And finally, with a nod to Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass, the initials of the characters taken together in the order of their appearances spell out the phrase "PublishAmerica is a vanity press." Take a look at the complete manuscript online -- it is a masterpiece of terrible writing.

The hoax here is utterly apparent to any objective reader. But that is not the reader for whom Atlanta Nights was written. It had one, and only one, reader in its sights. You guessed it. Following submission, Publish America promptly accepted Atlanta Nights for publication.

One is left to ponder: What is the real hoax here? Atlanta Nights or Publish America?