|

| E.B. White |

When is a children's book not just a children's book?

When it was written by E B White.

My youngest son and I are reading

Charlotte's Web. And, to be frank with you, I probably hadn't looked at the thing since I was in the 4th Grade myself. Maybe even the 3rd Grade

; I'm not sure when we read it in class.

Why address a children's book on a mystery blog?

Because I wish, now, that I'd re-read it several years ago. There's so much to learn about writing, inside. And, so much the book keeps reminding me about.

A Bit of a Shock

"Well, pull the book out of your backpack, little buddy, and let's take a look at it." That's what I told my son, when he said he had to read

Charlotte's Web for a school book report.

A moment later, the book was in my hands -- and I was floored!

I'd read the book as a kid. But, it was only as an adult that the author's name

lept off the cover at me. "

E B White?" I cried. "Son! This is written by

E B White!"

As if that would mean anything to him.

My wife stared at me, too.

I stared back, mouth open, no sound coming out, except a very thin

: "But

. . . It's E B White." How could I explain? How could I make them understand about those three or four copies of

Elements of Style that I'd murdered over the years -- not through book burnings or neglect, but through long, hard, rough use. Those little white paperbacks had been literally "dog-eared to death."

I felt a bit as if I'd just learned that God, himself, had taken pen in hand to write the

Mother Goose Stories.

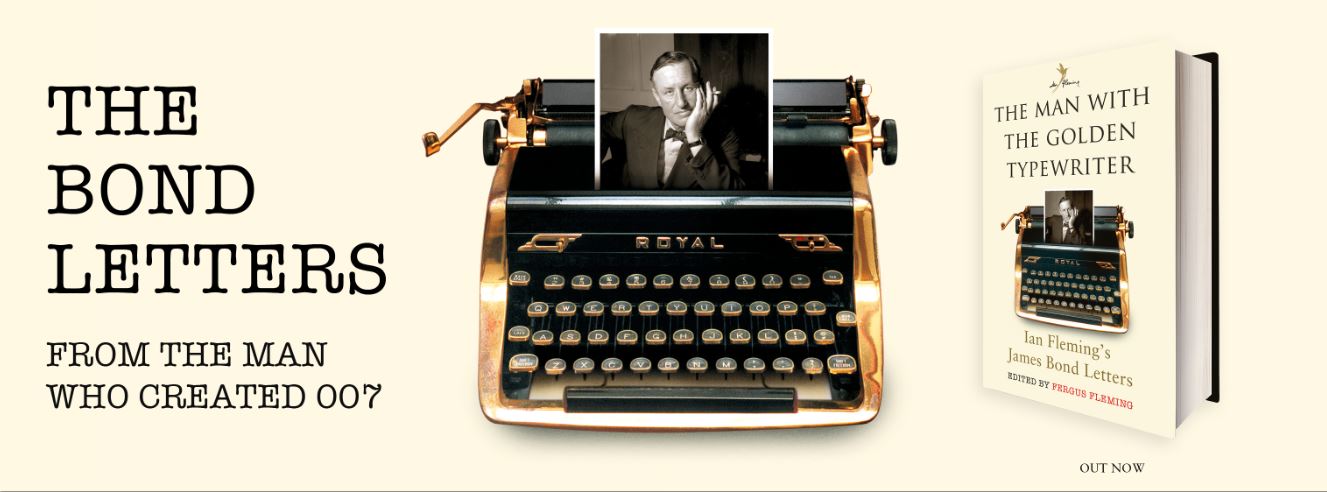

It was a much more powerful surprise, even, than the time I bought

Chitty-Chitty Bang-Bang! at a garage sale, only to discover it had been written by Ian Flemming. That's right. In case you didn't know,: the same Ian Flemming who wrote the original James Bond novels wrote

Chitty-Chitty Bang-Bang!Which makes sense in the context of the book, because -- when you think about it -- Chitty-Chitty Bang-Bang! (the car in the book) is really a kids' version of a James Bond spy car. And, the novel (obviously quite different from the movie) reads (IMHO) as a children's spy or mystery/suspense story.

Further

: For those who think only "little old ladies" write mysteries with recipes inside, I think it might be interesting to note that my copy of the book came with a recipe for brownies on the back page. And, clearly, Ian Flemming put it there, because, when the kids eat brownies, in the novel, there is a little aside explaining where to find the recipe, so the reader can try them him/herself.

But, what gets me about

Charlotte's Web has nothing to do with flying cars or brownies.

It's the Subtext

Several SS writers (myself included) have touched-on or examined differences between "literary works" and what are often referred to as "genre" works. But, one element I don't recall seeing explored in enough depth is that of

subtext, or

multi-layered meaning. This concept is very near-and-dear (let me know what you guys think of the hyphenation there) to those who love so-called "literary works", and it's one of the hallmarks critics point to, in order to determine if a work has literary merit.

I'm not talking about "Theme" here. I'm talking about the ability of a written passage, or passages, to be understood in an entirely different way, depending on the reader's viewpoint and experiences. On the most superficial level, the passage is an integral part of the work, and reads and functions that way

: it moves the plot forward, and characters continue to grow or change. Perhaps the reader gets a better feel for important setting details, or clues. Yet, at the same time, the passage is also open to interpretation, as a metaphor for one or more other ideas

; ideas quite different from the surface action or meaning.

My son and I have only made it to Chapter 4 or 5, so far. Wilbur the pig just recently met Charlotte the spider. And, this is a children's book; it's simple. Or, at least, appears to be simple. Yet, I was surprised to find several elements that veritably screamed at me with different meanings, all in such a short span of pages. Leave it to E B White to sew this incredibly rich subtext in such a small plot of fertile words.

But, a person may well ask, did E B White

intend us to see this subtext? Or did he write a simple children's story and

I'm loading it down with ideas that were never planted by the author? According to the literary critics:

It doesn't matter. The fact that a reader can view subtext -- even if that reader had to bring his own baggage along, to do so -- is what counts. Subtext is different for each reader, the idea goes, because everyone brings his/her own experience to the table, and this is how readers interact with literature. It's an important part of what makes Literature

literary.

So, please permit me to examine a little of

Charlotte's Web in these terms.

Lassie? Or something darker?

When Wilbur temporarily escapes from the barn, for instance, the farmer lures him back into his pen with a bucket of slop while the goose screams words to the effect: "Don't fall for it! It's the old Slop Bucket Trick! You'll be sorry."

My son, who looks at the book through the lens of an innocent nine-year-old, sees the farmer as acting in Wilbur's best interest. The farmer cares about the pig, and worries about him --

for Wilbur's sake. He helps Wilbur by returning him to the safety and security of the barn, and by feeding him warm food. My son equates the farmer with the way he would see a police officer or collie dog that helped him get back to the warmth of family and home, were my son to get lost.

As a nearly-fifty-year-old, who once had the dubious honor of slaughtering a cow with a sledge hammer, and has interacted in the sometimes (though not nearly as often as Hollywood would have us believe) duplicitous world of Military Intelligence and Special Operations, I understand that the farmer's caring has less to do with helping Wilbur, than it does with not letting Christmas dinner get away on the hoof. The farmer only cares about Wilbur, at this point, in the context of the pig's usefulness. The return to warmth and security is important because these elements are necessary if the farmer is to get the ham he plans to harvest near the holiday season. And, the slop bucket that Wilbur is lured back by, is an important part of that plan. Thus, Wilbur is lured back to a false security by his

very love for the thing that will increase the value -- in the farmer's eyes -- of Wilbur's eventual slaughter.

So, my son views this passage in terms of

Lassie Come Home while I view it as something more akin to Orwell's

Animal Farm, in which (if I recall correctly) the leader-pigs sell the old draft horse to the glue factory.

Is Charlotte a Capitalist

. . . Or just industrious?

|

| Cavatica or "Barn Spider" |

Shortly after Wilbur's return to captivity, he hears a disembodied voice that promises to be his friend. The next morning, he discovers that this voice belongs to Charlotte, the spider who built her web overhead, in the eaves of the barn. Her full name is Charlotte A. Cavatica.

Now, I'm constantly fascinated by the thought process behind naming fictional characters, and may explore the field more fully in a later post. In this case, however, a quick online search yielded a photo of a Cavatica spider -- otherwise known as a Barn Spider. Thus, Charlotte's name tells the reader (and the pig, if he has internet access or a good encyclopedia at hoof) what Charlotte is. At least on the surface.

But, what is she really?

Almost immediately after meeting Charlotte, Wilbur is horrified to watch as she sews-up a fly that got stuck in her web. And, he's further shocked and disgusted when she tells him that she plans to suck the fly's blood. When the little pig expresses his feelings, however, Charlotte basically tells him: "Well you may talk. You have your food brought to you. But, I suffer a much more precarious existence than you do, and have to work for my food. It may seem mean and vicious, but it's what I have to do to survive."

On the surface, a main character is introduced and we learn about her. We also see the beginnings of Wilbur's horrified loss of innocence. And, a key theme -- the seeming necessity to kill for nourishment -- is introduced.

Just beneath that surface, however, the two passages -- which comprise two back-to-back chapters -- can be read as a metaphor similar to

The Ant and the Grasshopper. Here, Wilbur is an ignorant version of the lazy grasshopper, in pig-form ("swine-a-morphised" perhaps??), while Charlotte is cast in the industrious ant's role (aracnimorphised?

;-). And, Charlotte is trying to explain these facts of life to a lazy (or simply ignorant) little pig.

On a third level, however, (And perhaps my earlier comparison to

Animal Farm, which sprang during the reading from I know not where, contributed to this interpretation.) the two chapters can be seen as an allegory for political, social or even economic ideas. Charlotte and Wilbur, who live in such close proximity, yet experience life in vastly different terms, may perhaps be considered to represent citizens of Capitalist nations (Charlotte), who have to fend for themselves and face the reality of quite possibly starving if they don't work hard and effectively to secure food and shelter, and citizens of Communist or Socialist nations (Wilbur), in which people tend to be more state-reliant for their sustenance

That Charlotte has to build and maintain her own web (which might, therefor, be seen as belonging to her), while Wilbur is housed and fed by an authority figure (the farmer, who clearly owns the barn and food, which keep Wilbur alive and well), lends further credence to this view.

A right-wing reactionary might even view Wilbur's state of false-security (He's warm and happy now, but the farmer will kill him when the time is right) as being illustrative of the "evils of communism." Wilbur has been "tricked," in this viewpoint, into surrendering his freedom for what seems like security. Meanwhile, Charlotte is the rugged individualist who stands on her own eight legs.

A left-wing radical, on the other hand, while still viewing the selection as a comment on Capitalism vs. Communism, might note how it stresses the innocence and trusting nature of the (socialist) pig, versus the greed and callousness of the (capitalist) spider.

Two chapters in a simple children's book. But, at least three or four different ways of looking at it. Such a tangled web of meaning, in so few words. Now that, to me, is Subtext.

Deconstructing a children's book may seem ludicrous on a blog that's about writing for adults. . .

But

Charlotte's Web has reminded me that my favorite books are those loaded with subtext. Books and stories that have several layers of meaning

; layers I can sit back and consider, weigh and examine, long after I've finished reading.

If I'm honest with myself, I have to admit that my writing suffers from a certain lack of subtext. And, putting it in there is a tricky business --

to say the least! I'm reminded now, however, of the importance of trying to get it in there, of trying to push the boundaries of the meaning behind the words on the paper.

We often speak of the necessity of making words carry as much work as they can -- particularly in short stories, where the space is so limited. But, are we succeeding to the best of our abilities if we don't try to make the work of those words include creation of subtext? I can only answer -- with a guilty "No" -- for myself.

Meanwhile, my son and I will continue to read

Charlotte's Web, and we'll continue to discuss the surface context, while I gently try to get him to consider subtext as we go along.

He wants to keep reading because the little girl who rescued Wilbur from being slaughtered as a runt hasn't visited Wilbur in quite some time. My son and I both think she'll return for a visit before the book is over. He wants to see this happen, so he can learn why she disappeared for so long, leaving the little pig lonely and sad.

I'm nearly fifty, and I've known a lot of little girls. I'm not surprised by her disappearance. Yet, I too, await her return -- with great anticipation. Because I want to see how both the pig and the girl have changed in the interim.

See you in two weeks!

--Dixon

This week I opened a quart carton of orange sherbet. Yum. I've had orange sherbet through the years yet, somehow, this time my childhood memories flooded back (maybe old age kicking in, who knows?) I suddenly felt as if I were eleven again, visiting my dad for the summer in Fort Worth, Texas. My parents divorced when I was young. Both parents remarried and during the whole school year, I lived with my mother, step-dad and two little sisters, out on the high plains of Texas, forty miles from Lubbock in the small town of Post, TX. Post then had a population of about three thousand folks and this was back in the olden days when ice cream was only available in grocery stores and drug stores. The most flavors I remember were vanilla, chocolate, Neapolitan, and strawberry. In the summer, when I went to visit my dad in the big city of Fort Worth for a couple of weeks, one of the first things we did was to drive over to Baskin Robbins where, at that time, they offered thirty-one flavors of ice cream. I'd look at everything they had and every single time order the same thing...orange sherbet, served in an ice cream cone. I have no idea why. They had banana nut, peppermint, chocolate mint, cherry vanilla, regular vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, peach, Neapolitan, and something with nuts, maybe butter pecan. They also had orange, lime and pineapple sherbet. I don't remember any of the other thirty-one flavors but for some strange reason orange sherbet really seemed like the best of the best to me and that's what I'd buy.

This week I opened a quart carton of orange sherbet. Yum. I've had orange sherbet through the years yet, somehow, this time my childhood memories flooded back (maybe old age kicking in, who knows?) I suddenly felt as if I were eleven again, visiting my dad for the summer in Fort Worth, Texas. My parents divorced when I was young. Both parents remarried and during the whole school year, I lived with my mother, step-dad and two little sisters, out on the high plains of Texas, forty miles from Lubbock in the small town of Post, TX. Post then had a population of about three thousand folks and this was back in the olden days when ice cream was only available in grocery stores and drug stores. The most flavors I remember were vanilla, chocolate, Neapolitan, and strawberry. In the summer, when I went to visit my dad in the big city of Fort Worth for a couple of weeks, one of the first things we did was to drive over to Baskin Robbins where, at that time, they offered thirty-one flavors of ice cream. I'd look at everything they had and every single time order the same thing...orange sherbet, served in an ice cream cone. I have no idea why. They had banana nut, peppermint, chocolate mint, cherry vanilla, regular vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, peach, Neapolitan, and something with nuts, maybe butter pecan. They also had orange, lime and pineapple sherbet. I don't remember any of the other thirty-one flavors but for some strange reason orange sherbet really seemed like the best of the best to me and that's what I'd buy.