Atlanta, the Deep South, in 1948. The war changed a lot of things, but the immediate postwar world, in the U.S., was in many ways a turning back of the clock. Women in the workplace, like black guys in uniform, were wartime adjustments. The unions had been bottled up, part of the war effort, and there was no reason to let a bunch of Jews and Reds wave the Hammer-and-Sickle. Jim Crow was both custom and law, and things were gonna be the way they were before, when people knew their place. And if they forgot themselves, there were the night-riders, the Klan. Not that good people subscribe to violence, but when every Christian value is threatened with contamination, where can you turn?

All right. The obvious irony, first, that we're talking about white values. And secondly, was it in fact that bad, in the South, for black people? Well, yes. All you have to do is ask. It's a time in living memory. Equally obviously, not just in the South, either. But in a town like Atlanta, it was institutional. This is the world of Thomas Mullen's novels Darktown and Lightning Men, a world of tensions and temperament, accommodations and anxiety. A place of comforting convention and uncomfortable energies.

Some of you probably know I have a weakness for this time period, the late 1940's, and I've written a series of noir stories that take place back then. The stories involve the people and events of the time and place, and usually touch on some cultural or political ferment, the Red Scare, the mob takeover of the waterfront, running guns to Ireland or Palestine. One in particular, "Slipknot," takes a sidelong glance at race, in the context of fixing the book on a high-stakes pool game. The principals are two historical figures, rival gangsters Owney Madden, owner of the Cotton Club, and Bumpy Johnson, boss of the Harlem numbers. I have no idea whether these guys actually butted heads, back in the day, but it felt right to put them at odds. It was a way of sharpening the racial edge, to make it personal, an open grievance. And neither of them what you might call black-and-white, but equal parts charm and menace.

This is true of Thomas Mullen's books. They're about the color bar, in large degree, but one thing they're not is black-and-white. There are good people, and bad, and mostly in between, just like it is. Darktown is maybe the more traditional as a thriller, with its echoes of True Confessions, and Lightning Men less about a single criminal act than it is about a climate of violence, but both books are effectively novels of manners. You might be put in mind of Lehane or Walter Mosley, but I think the presiding godfather of the books is Chester Himes. Mullen is the more supple writer by far - which isn't to disrespect Himes, but let's be honest, he's working the same groove as Jim Thompson, it's lurid and it's unapologetically pulp - and Mullen's characters are round, not flat (E.M. Forster's usage). All the same, there's something about the weight these people carry, their mileage, their moral and physical exhaustion. This is material Himes took ownership of, and Mullen inhabits it like the weather, We all get wet in the same rain.

Don't mistake me. These books aren't dour. We're not talking Theodore Dreiser. Mullen's writing is lively and exact. He's sometimes very funny. He's got balance, he's light on his feet. And he does a nice thing with voice. The books are told with multiple POV, shifting between five or six major characters, black and white, male and female. You always know who it is, because the narrative voice rings true. The situation is lived-in. You feel your way into its physicality, and you can take the emotional temperature. You don't hang up on it, thinking, that's not a genuine black person speaking, or that's not white.

I realize I've been talking about theme, for the most part, and not giving you the flavor. Here's a cop in a bar.

He lifted the glass, nothing but three sad memories of larger ice cubes. "I'll take another."

When Feckless returned the full glass, it rested atop an envelope. Smith looked up at Feck, who peeled the triangle away and revealed cash stuffed inside.

That there was a lot of money, Smith saw. "I don't do that," he said, looking Feck in the eye.

"Pass it on to Malcolm, then. He could use it."

"He'd be very grateful. But you can give it to him yourself." Smith stood and walked away, leaving the full glass behind him as well, and wondering what lay at the end of the road he hadn't chosen.

Not that he isn't tempted. That's the underlying tension, the spine. What lies at the end of the road you don't take? What lies at the end of the road you do? Personal character - moral character, integrity - is about what you do when the going gets tough, not when it's easy, how you behave when you don't want to disappoint yourself. It's self-respect. It's not Jiminy Cricket, or concern for appearances. This is the engine that drives everyone in the books, whether toward good ends or bad. If you've got nothing to live with but your own shame, you've got nothing left to fight for.

28 February 2018

Heat Lightning

Labels:

Atlanta,

David Edgerley Gates,

police,

South,

stories

27 February 2018

Rejected!

I have every rejection I’ve ever received.

All 2,552 of them.

When I began writing in the mid-1970s, conventional wisdom—whether true or not—was that a collection of rejection slips would prove beneficial were the IRS ever to audit my taxes. The very existence of the rejection slips proved I was writing with the intent to earn money and not as a hobby, even though I was operating at a loss. These days my taxable net profit on freelancing proves the point far better than my collection of rejection slips, but I can’t stop myself from collecting them.

Though today’s rejections are nowhere near as physically varied as the ones I once received through the mail, I continue to print out emailed rejections and file them with all the other rejection slips, which now fill most of a filing cabinet drawer.

JUST SAY NO

I received my first rejection slip from Fantasy & Science Fiction in September 1974, just as I began my senior year of high school, and I received my first personalized rejection—a quarter-page typewritten note with a handwritten addendum—from the editor of Multitude in May 1976, less than a year after high school graduation. I had progressed from form rejection to personalized rejection in only seven submissions.

Of course, a personalized rejection still means “no.”

My goal was to collect acceptances, not rejections, so I persevered: A single rejection the first year, four the second, 34 the third, and a whopping 74 the fourth. They came in all sizes and shapes, from scraps of paper containing a simple scrawled note (Sam Merwin, Jr., rejecting a story sent to Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine) to four-color full-page form rejection letters that cost more to print than I earned from many of my earliest sales.

Most rejections provided little information beyond the preprinted message. Others contained checklists where editors, by one or more strokes of the pen, identified the way or ways my story failed to engage them. Still others provided handwritten words of encouragement: “Not bad,” “Fine writing,” and “Try us again.”

The best—though they were still rejections—were the long notes and letters providing detailed reasons for rejection and providing suggestions for improvement. Sometimes, they even provided lessons on writing: Gentleman’s Companion editor Ted Newsom’s page-and-a-half letter on the value of writing transitions rather than using jump-cuts springs to mind, as do several letters from horror anthologist Charles L. Grant and several incredibly detailed, multi-page letters from Amazing Stories editor Kim Mohan. (Note: I placed two stories with Ted Newsom and one with Charles L. Grant, but I never did place one with Kim Mohan.)

And one rejection, from Mystery Street, may have been my first encounter with fellow SleuthSayer O’Neil De Noux!

THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON REJECTIONS

During the 40-plus years I’ve been writing, my stories have been rejected by 71 mystery periodicals—the five that existed in the 1980s and 66 more since then—and an uncounted number of mystery anthologies, including both print and electronic publications. (Note: In “Poster Child,” my recent guest post at Something is Going to Happen, I actually name the many mystery periodicals that have come and mostly gone since I began writing short mystery fiction.)

I’m unsure if a multitude of rejections indicates when I’m having a good year or a bad year, but I received 204 rejections in 1991 (I received 84 acceptances that year). On the flip side, I received only three in 1989 (I received four acceptances that year). More recently, acceptances and rejections are near equilibrium: 39 rejections vs. 37 acceptances in 2017; 35 rejections vs. 45 acceptances in 2016; and 31 rejections vs. 42 acceptances in 2015.

Though the majority of rejections are in response to short story submissions, mixed among the many early rejections are those for articles, essays, fillers, poems, and short humor. I was shotgunning the market back then, trying anything and everything, and hoping something stuck. (And not every rejection generates a rejection slip—Woman’s World, for example, does not send rejections—so I’ve received more rejections than rejection slips.)

Rejections mess with your head. Being told no 2,552 times is quite disheartening. Some writers give up after the first few dozen. Other writers receive rejections and only become more determined. Many writers play rejectomancy, attempting to read between the lines of every rejection. (Aeryn Rudel, in his blog Rejectomancy, which I follow, attempts to decode and rank rejections into various tiers, from “Common Form Rejections” to “Higher-Tier Form Rejections.” Though most of Aeryn’s data comes from the horror, science fiction, and fantasy markets, the information he provides is both entertaining and informative.)

REJECTION-FREE IS THE WAY TO BE

Were it not for the lessons I learned from those long, detailed rejection letters, I may have become one of the many would-be writers whose shattered egos and unpublishable manuscripts litter the literary highway. Lack of ability quashed my music career and my artwork never gained traction, so I focused my creative energy on writing and, over time, began to accumulate acceptances: 1,584 of them (more than 1,200 are for short stories).

That’s one acceptance for every 1.61 rejections and, yes, I’ve kept every acceptance letter, postcard, note, and email. Those I file with hardcopies of my manuscripts and, when I get them, with copies of the actual publications.

I had a hot streak a few years back, when almost everything I wrote sold on first submission. My ego expanded exponentially, but then I realized something I should have realized long before that: If everything is selling, I’m not challenging myself; I’m taking the easy path to publication.

So, I began writing stories that stretched my abilities, either by working in unfamiliar genres or by submitting to higher-paying and more prestigious markets. The acceptance-to-rejection ratio shifted, and not in my favor. I placed a few stories, and just in time because two of my sure-sale markets ceased publication and several anthology editors with whom I worked stopped editing anthologies.

So, as I continue stretching my abilities and my stories continue facing the submission gauntlet, my rejection collection grows, taking ever more space in my filing cabinet. Luckily, so does my acceptance collection.

A trio of recently published stories survived the submission gauntlet: “Plumber’s Helper” in The Saturday Evening Post, “My Stripper Past” in Pulp Adventures #28, and “The Mourning Man” in the March/April Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. (Note: Joining me with stories in this issue are two other SleuthSayers: R.T. Lawton and Robert Lopresti.)

All 2,552 of them.

When I began writing in the mid-1970s, conventional wisdom—whether true or not—was that a collection of rejection slips would prove beneficial were the IRS ever to audit my taxes. The very existence of the rejection slips proved I was writing with the intent to earn money and not as a hobby, even though I was operating at a loss. These days my taxable net profit on freelancing proves the point far better than my collection of rejection slips, but I can’t stop myself from collecting them.

Though today’s rejections are nowhere near as physically varied as the ones I once received through the mail, I continue to print out emailed rejections and file them with all the other rejection slips, which now fill most of a filing cabinet drawer.

JUST SAY NO

I received my first rejection slip from Fantasy & Science Fiction in September 1974, just as I began my senior year of high school, and I received my first personalized rejection—a quarter-page typewritten note with a handwritten addendum—from the editor of Multitude in May 1976, less than a year after high school graduation. I had progressed from form rejection to personalized rejection in only seven submissions.

Of course, a personalized rejection still means “no.”

|

| The typing is mine, the handwriting is Sam's |

Most rejections provided little information beyond the preprinted message. Others contained checklists where editors, by one or more strokes of the pen, identified the way or ways my story failed to engage them. Still others provided handwritten words of encouragement: “Not bad,” “Fine writing,” and “Try us again.”

|

| O'Neil De Noux fails to recognize the genius of my early work |

And one rejection, from Mystery Street, may have been my first encounter with fellow SleuthSayer O’Neil De Noux!

THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON REJECTIONS

During the 40-plus years I’ve been writing, my stories have been rejected by 71 mystery periodicals—the five that existed in the 1980s and 66 more since then—and an uncounted number of mystery anthologies, including both print and electronic publications. (Note: In “Poster Child,” my recent guest post at Something is Going to Happen, I actually name the many mystery periodicals that have come and mostly gone since I began writing short mystery fiction.)

I’m unsure if a multitude of rejections indicates when I’m having a good year or a bad year, but I received 204 rejections in 1991 (I received 84 acceptances that year). On the flip side, I received only three in 1989 (I received four acceptances that year). More recently, acceptances and rejections are near equilibrium: 39 rejections vs. 37 acceptances in 2017; 35 rejections vs. 45 acceptances in 2016; and 31 rejections vs. 42 acceptances in 2015.

Though the majority of rejections are in response to short story submissions, mixed among the many early rejections are those for articles, essays, fillers, poems, and short humor. I was shotgunning the market back then, trying anything and everything, and hoping something stuck. (And not every rejection generates a rejection slip—Woman’s World, for example, does not send rejections—so I’ve received more rejections than rejection slips.)

Rejections mess with your head. Being told no 2,552 times is quite disheartening. Some writers give up after the first few dozen. Other writers receive rejections and only become more determined. Many writers play rejectomancy, attempting to read between the lines of every rejection. (Aeryn Rudel, in his blog Rejectomancy, which I follow, attempts to decode and rank rejections into various tiers, from “Common Form Rejections” to “Higher-Tier Form Rejections.” Though most of Aeryn’s data comes from the horror, science fiction, and fantasy markets, the information he provides is both entertaining and informative.)

REJECTION-FREE IS THE WAY TO BE

Were it not for the lessons I learned from those long, detailed rejection letters, I may have become one of the many would-be writers whose shattered egos and unpublishable manuscripts litter the literary highway. Lack of ability quashed my music career and my artwork never gained traction, so I focused my creative energy on writing and, over time, began to accumulate acceptances: 1,584 of them (more than 1,200 are for short stories).

That’s one acceptance for every 1.61 rejections and, yes, I’ve kept every acceptance letter, postcard, note, and email. Those I file with hardcopies of my manuscripts and, when I get them, with copies of the actual publications.

I had a hot streak a few years back, when almost everything I wrote sold on first submission. My ego expanded exponentially, but then I realized something I should have realized long before that: If everything is selling, I’m not challenging myself; I’m taking the easy path to publication.

So, I began writing stories that stretched my abilities, either by working in unfamiliar genres or by submitting to higher-paying and more prestigious markets. The acceptance-to-rejection ratio shifted, and not in my favor. I placed a few stories, and just in time because two of my sure-sale markets ceased publication and several anthology editors with whom I worked stopped editing anthologies.

So, as I continue stretching my abilities and my stories continue facing the submission gauntlet, my rejection collection grows, taking ever more space in my filing cabinet. Luckily, so does my acceptance collection.

A trio of recently published stories survived the submission gauntlet: “Plumber’s Helper” in The Saturday Evening Post, “My Stripper Past” in Pulp Adventures #28, and “The Mourning Man” in the March/April Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. (Note: Joining me with stories in this issue are two other SleuthSayers: R.T. Lawton and Robert Lopresti.)

26 February 2018

To Pay or Not to Play...

by Steve Liskow

by Steve Liskow

A contest I used to enter regularly (It was free, see below) now sports the following headline on its web page: "Submissions for the 2017 **** Contest are closed. The 2018 contest will open on January 1, 2018." Today is February 26 and that banner was still there when I uploaded this essay.

Yesterday, I found a website for a magazine with exactly the same message. Their submission period will open "sometime after January 1, 2018."

Not encouraging...

When I was trying to break into publishing (An accurate phrase for a crime writer, right?), people urged me to enter contests. If I won, I'd catch the attention of editors and agents, and they'd take me more seriously.

But not all contests and awards are created equal. Winning a Pulitzer, an Agatha or an Edgar means something. Second runner-up in the Oblivion County Limerick Derby won't raise many eyebrows.

There are a few problems every writer encounters in writing contests--or even submitting to a magazine or anthology--but I've learned to recognize warning signs.

One is a website that's hard to navigate, or that's out of date, like the two I mentioned above. If you can't find details like a theme, length, formatting, or if there's an entry fee (more about that in a few minutes), you should look elsewhere.

Another is weird judging or criteria.

Yes, no matter how much the judges have a rubric, at some point personal preference will come into play. Every time you send something out, subjectivity is a fact of life, but it should be less crucial in a contest than for regular publication...especially if you pay an entry fee. You won't know this until it's too late, but don't make the same mistake twice.

One judge doesn't like profanity, another doesn't appreciate your humor, and a third wants more violence or a sympathetic female character. I have withdrawn stories from two anthologies (Both later published somewhere else) because I discovered the judges didn't understand their own criteria.

I added one sentence to one story to make it fit a theme, and on a scale of 1 (low) to 4 (high) the three judges gave me 1, 3, and 4 on how well I adhered to that theme. Not possible.

In another contest, the sponsors sent me my scores and I saw ratings of 56, 94, and 89. Two judges loved the story and the other gave me low scores on almost every standard. The judge who gave me a 94 total only gave me a 1 (out of 5) for relative quality of the story compared to the others he or she read. Really?

I've mentioned cost a because I'm cheap. If the submission involves a reading fee, look at the prize. I won't pay $25 for a $100 prize. I enter few contests that involve reading fees anymore. There has to be a good return, meaning at least two of the following: money, exposure, prestige.

I avoid one contest because it published the deal-breaker right up front. They offered a $250 prize (not bad) with a $20 reading fee (ummm...) BUT the judges reserved the right to award no prize if they felt on entry deserved it. Nothing was said about refunding the fees.

Oops.

Yeah, I still enter a few contests, but now I need a Plan B, other places I can send a story if it doesn't win. Last summer, I sent a story to an anthology. It wasn't chosen, so I entered it in a contest with a hefty cash prize. I learned last week that it didn't win and sent it to two regular markets. I have three other places to send it if neither of those pick it up.

Prestige is nice, and so is exposure, but in the words of Samuel Johnson, "No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money."

A contest I used to enter regularly (It was free, see below) now sports the following headline on its web page: "Submissions for the 2017 **** Contest are closed. The 2018 contest will open on January 1, 2018." Today is February 26 and that banner was still there when I uploaded this essay.

Yesterday, I found a website for a magazine with exactly the same message. Their submission period will open "sometime after January 1, 2018."

Not encouraging...

When I was trying to break into publishing (An accurate phrase for a crime writer, right?), people urged me to enter contests. If I won, I'd catch the attention of editors and agents, and they'd take me more seriously.

But not all contests and awards are created equal. Winning a Pulitzer, an Agatha or an Edgar means something. Second runner-up in the Oblivion County Limerick Derby won't raise many eyebrows.

There are a few problems every writer encounters in writing contests--or even submitting to a magazine or anthology--but I've learned to recognize warning signs.

One is a website that's hard to navigate, or that's out of date, like the two I mentioned above. If you can't find details like a theme, length, formatting, or if there's an entry fee (more about that in a few minutes), you should look elsewhere.

Another is weird judging or criteria.

Yes, no matter how much the judges have a rubric, at some point personal preference will come into play. Every time you send something out, subjectivity is a fact of life, but it should be less crucial in a contest than for regular publication...especially if you pay an entry fee. You won't know this until it's too late, but don't make the same mistake twice.

One judge doesn't like profanity, another doesn't appreciate your humor, and a third wants more violence or a sympathetic female character. I have withdrawn stories from two anthologies (Both later published somewhere else) because I discovered the judges didn't understand their own criteria.

I added one sentence to one story to make it fit a theme, and on a scale of 1 (low) to 4 (high) the three judges gave me 1, 3, and 4 on how well I adhered to that theme. Not possible.

In another contest, the sponsors sent me my scores and I saw ratings of 56, 94, and 89. Two judges loved the story and the other gave me low scores on almost every standard. The judge who gave me a 94 total only gave me a 1 (out of 5) for relative quality of the story compared to the others he or she read. Really?

I've mentioned cost a because I'm cheap. If the submission involves a reading fee, look at the prize. I won't pay $25 for a $100 prize. I enter few contests that involve reading fees anymore. There has to be a good return, meaning at least two of the following: money, exposure, prestige.

I avoid one contest because it published the deal-breaker right up front. They offered a $250 prize (not bad) with a $20 reading fee (ummm...) BUT the judges reserved the right to award no prize if they felt on entry deserved it. Nothing was said about refunding the fees.

Oops.

Yeah, I still enter a few contests, but now I need a Plan B, other places I can send a story if it doesn't win. Last summer, I sent a story to an anthology. It wasn't chosen, so I entered it in a contest with a hefty cash prize. I learned last week that it didn't win and sent it to two regular markets. I have three other places to send it if neither of those pick it up.

Prestige is nice, and so is exposure, but in the words of Samuel Johnson, "No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money."

Labels:

contests,

guidelines,

markets,

reading fees,

Steve Liskow

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

25 February 2018

Bad Good Guys ~ Good Bad Guys

by Leigh Lundin

Noting that bad guys can be more interesting than good guys is neither new nor profound. Why else would Dantean classics courses consistently teach Inferno rather than Paradiso?

Even as we aspire to the light of goodness and grace, often darkness muddies our thoughts and actions. Our limbs stretch toward the heavens but our roots point toward hell.

So it is with story-telling. Bad guys make or break a tale. Take the James Bond series. The best films feature the evilest of the nefarious. Huge and hulking may frighten, but sheer terror runs deeper.

Take a little five-foot-nothing Russian named Rosa, played by Lotte Lenya. Bring to mind Colonel Klebb with her spiked sensible shoes, and you touch the stuff that gave 007 nightmares. (Lotte Lenya’s husbands died– all of them– just sayin’.)

Bad guys must possess the potential to overpower the good folks. Take the battle of David and Goliath.

Take the Fantastic Four movies. It’s hardly fair to pit four against one, no matter how fearsome that one bad guy is. It’s just not cricket. Michael Chiklis, yeah, he was pretty good in the original version, but it’s not enough to maintain attention. You’d have thought Marvel would have learnt its lesson in 2005, but ten years later, they made the same mistakes… only worse.

Hungarian Historical

I came across an obscure adventure mystery movie making the rounds of internet television video distributors, presently on FilmRise and CoolFlix. Titled Day of Wrath, it appeared difficult to track down until I discovered it also went by the name Game of Swords.

IMDB awarded Game of Swords an unimpressive 5.6/10, whilst Rotten Tomatoes stamped Day of Wrath a hostile audience rating of 24%. Fortunately I knew nothing of this before watching.

“Fortunately” I say because overall I liked the plot, setting, and cast except for one key character, which I’ll return to.

Set in 1542 Spain during the Inquisition, the story follows a sheriff as he investigates the murders of nobles. The deeper he digs, the more he puts his and his family’s lives at risk, until he suspects some connection between his family and the conspiracy he’s chipping away at.

The story line proves devious but neither contrived nor overdone. The thought-provoking plot wraps up with a couple of satisfying twists. The writers deserve high marks. As for cast…

The town is rife with bad guys, some you hate, some you loathe, and others… not so much. I introduce Lukács Bicskey who plays the part of hired gun, Miguel de Alvarado. His character translates as complex and nuanced, his glacier ice-blue eyes continuously appraising, evaluating. Meeting Bicskey is like coming across a wolf in the forest, one who knows its own prowess, utterly fearless, consummately lethal, and yet…

He’s dimensional, more than meets the eye. The Hungarian actor projects the same chill don’t-ƒ-with-the-psychopath as Lee Van Cleef and is maybe just as underrated. He won’t be making any more movies– he died in 2015– but in this one performance, I’d nominated him for the John Floyd Best Bad Guys Ever Award.

If the plot is great and most of the cast is superlative, why the low ratings? My conclusion traces the problem to the film’s star, a hero about as vibrant as Valium, looking like Fabio on a lank-hair day.

Who? American actor Christopher Lambert. He’s appeared in a string of US and European movies since 1980. He often assumes action röles such as Tarzan, Beowulf, and Connor MacLeod in Highlander. In this film, he plods through the part as if we interrupted his nap time. The man’s performance subsumes sole responsibility for extinguishing one or two stars from critics’ ratings.

Setting Lambert aside, I liked this underrated film a lot. Despite verbiage about American World Pictures, the movie is a Hungarian-British enterprise. The Hungarian actors performed well, certainly better than our hero.

For a well-plotted story with one of the most interesting bad guys in filmdom, see it. As mentioned earlier, it’s free right now on FilmRise channels like CoolFlix. Definitely worth the price.

|

| From Russia with Love |

So it is with story-telling. Bad guys make or break a tale. Take the James Bond series. The best films feature the evilest of the nefarious. Huge and hulking may frighten, but sheer terror runs deeper.

Take a little five-foot-nothing Russian named Rosa, played by Lotte Lenya. Bring to mind Colonel Klebb with her spiked sensible shoes, and you touch the stuff that gave 007 nightmares. (Lotte Lenya’s husbands died– all of them– just sayin’.)

Bad guys must possess the potential to overpower the good folks. Take the battle of David and Goliath.

“It’s ESPN Sports Night here at the arena where the Philistines face off against the Israelites.”We love it when an underdog wins. If Goliath had wiped out David, no one would have recorded the event.

“That’s right, Bob. The crowds cheer wildly here in Elah. The reigning champion, Golly G, is warming up and eating a… is that an ox leg?”

“It sure is, Dan. Looks like a mere buffalo wing in those massive paws. His masseuses, all ten of them, are working him over, broad shoulders to feet the size of sleds.”

“Bob, in fairness, we should turn our attention a moment from the big guy to his opponent, little Davy ben Jesse. He hails from Bethlehem, known for steel in its sinews. Young Dave’s oh-for-twenty-seven, but due for a break.”

“And a break he’ll find, Dan, if Goliath gets his hands on him. Gol’s real problem, same as Jordan has, little guys ducking beneath the legs and wreaking havoc.”

“The Israelites claim they’ve a real secret weapon in their Dave. Manager Saul says they’re prepared to kick Philly ass, and that’s a quote.”

“Dan, they’re pulling off the robes and I got to admit, not an ounce of fat on little David.”

“Nor muscle either, Bob. The big guy’s rolling his shoulders and… there’s the bell!”

“Two strides out of his corner… and Golly winds up his infamous ring-dat-bell strongman move and… Splat? That’s it?”

“What just happened? The highly-touted Davy is nothing but a little greasy spot on the canvas?”

“Two-point-two seconds, Dan. That’s got to be some kind of record.”

“Cut! That’s not sporting.”

“This has been ESPN’s coverage of the match here in Elah, sure to be a disappointment in the record books not to mention holders of those ninety-schekel tickets. Wrap it, boys. Can we still catch the bus to Jericho?”

Take the Fantastic Four movies. It’s hardly fair to pit four against one, no matter how fearsome that one bad guy is. It’s just not cricket. Michael Chiklis, yeah, he was pretty good in the original version, but it’s not enough to maintain attention. You’d have thought Marvel would have learnt its lesson in 2005, but ten years later, they made the same mistakes… only worse.

Hungarian Historical

I came across an obscure adventure mystery movie making the rounds of internet television video distributors, presently on FilmRise and CoolFlix. Titled Day of Wrath, it appeared difficult to track down until I discovered it also went by the name Game of Swords.

IMDB awarded Game of Swords an unimpressive 5.6/10, whilst Rotten Tomatoes stamped Day of Wrath a hostile audience rating of 24%. Fortunately I knew nothing of this before watching.

“Fortunately” I say because overall I liked the plot, setting, and cast except for one key character, which I’ll return to.

Set in 1542 Spain during the Inquisition, the story follows a sheriff as he investigates the murders of nobles. The deeper he digs, the more he puts his and his family’s lives at risk, until he suspects some connection between his family and the conspiracy he’s chipping away at.

|

|

The story line proves devious but neither contrived nor overdone. The thought-provoking plot wraps up with a couple of satisfying twists. The writers deserve high marks. As for cast…

The town is rife with bad guys, some you hate, some you loathe, and others… not so much. I introduce Lukács Bicskey who plays the part of hired gun, Miguel de Alvarado. His character translates as complex and nuanced, his glacier ice-blue eyes continuously appraising, evaluating. Meeting Bicskey is like coming across a wolf in the forest, one who knows its own prowess, utterly fearless, consummately lethal, and yet…

He’s dimensional, more than meets the eye. The Hungarian actor projects the same chill don’t-ƒ-with-the-psychopath as Lee Van Cleef and is maybe just as underrated. He won’t be making any more movies– he died in 2015– but in this one performance, I’d nominated him for the John Floyd Best Bad Guys Ever Award.

If the plot is great and most of the cast is superlative, why the low ratings? My conclusion traces the problem to the film’s star, a hero about as vibrant as Valium, looking like Fabio on a lank-hair day.

Who? American actor Christopher Lambert. He’s appeared in a string of US and European movies since 1980. He often assumes action röles such as Tarzan, Beowulf, and Connor MacLeod in Highlander. In this film, he plods through the part as if we interrupted his nap time. The man’s performance subsumes sole responsibility for extinguishing one or two stars from critics’ ratings.

Setting Lambert aside, I liked this underrated film a lot. Despite verbiage about American World Pictures, the movie is a Hungarian-British enterprise. The Hungarian actors performed well, certainly better than our hero.

For a well-plotted story with one of the most interesting bad guys in filmdom, see it. As mentioned earlier, it’s free right now on FilmRise channels like CoolFlix. Definitely worth the price.

Labels:

bad guys,

inquisition,

Leigh Lundin,

Lukács Bicskey,

villains

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

24 February 2018

How long should we write?

Bad Girl confronts the hard question

by Melodie Campbell (Bad Girl)

Is there an age at which we should stop writing novels? Philip Roth thought so. In his late seventies, he stopped writing because he felt his best books were behind him, and any future writing would be inferior. (His word.)

A colleague, Barbara Fradkin, brought this to my attention the other day, and it started a heated discussion.

Many authors have written past their prime. I can name two (P.D. James and Mary Stewart) who were favourites of mine. But their last few books weren’t all that good, in my opinion. Perhaps too long, too ponderous; plots convoluted and not as well conceived…they lacked the magic I associated with those writers. I was disappointed. And somewhat embarrassed.

What an odd reaction. I was embarrassed for my literary heroes, that they had written past their best days. And I don’t want that to happen to me.

The thing is, how will we know?

One might argue that it’s easier to know in these days with the Internet. Amazon reviewers will tell us when our work isn’t up to par. Oh boy, will they tell us.

But I want to know before that last book is released. How will I tell?

The Idea-Well

I’ve had 100 comedy credits, 40 short stories and 14 books published. I’m working on number 15. That’s 55 fiction plots already used up. A lot more, if you count the comedy. How many original plot ideas can I hope to have in my lifetime? Some might argue that there are no original plot ideas, but I look at it differently. In the case of authors who are getting published in the traditional markets, every story we manage to sell is one the publisher hasn’t seen before, in that it takes a different spin. It may be we are reusing themes, but the route an author takes to send us on that journey – the roadmap – will be different.

One day, I expect my idea-well will dry up.

The Chess Game You Can’t Win

I’m paraphrasing my colleague here, but writing a mystery is particularly complex. It usually is a matter of extreme planning. Suspects, motives, red herrings, multiple clues…a good mystery novel is perhaps the most difficult type of book to write. I liken it to a chess game. You have so many pieces on the board, they all do different things, and you have to keep track of all of them.

It gets harder as you get older. I am not yet a senior citizen, but already I am finding the demands of my current book (a detective mystery) enormous. Usually I write capers, which are shorter but equally meticulously plotted. You just don’t sit down and write these things. You plan them for weeks, and re-examine them as you go. You need to be sharp. Your memory needs to be first-rate.

My memory needs a grade A mechanic and a complete overhaul.

The Pain, the Pain

Ouch. My back hurts. I’ve been here four hours with two breaks. Not sure how I’m going to get up. It will require two hands on the desk, and legs far apart. Then a brief stretch before I can loosen the back so as not to walk like an injured chimp.

My wrists are starting to act up. Decades at the computer have given me weird repetitive stress injuries. Not just the common ones. My eyes are blurry. And then there’s my neck.

Okay, I’ll stop now. If you look at my photo, you’ll see a smiling perky gal with still-thick auburn hair. That photo lies. I may *look* like that, but…

You get the picture <sic>.

Writing is work – hard work, mentally and physically. I’m getting ready to face the day when it becomes too much work. Maybe, as I find novels more difficult to write, I’ll switch back to shorter fiction, my original love. If these short stories continue to be published by the big magazines (how I love AHMM) then I assume the great abyss is still some steps away.

But it’s getting closer.

How about you? Do you plan to write until you reach that big computer room in the sky?

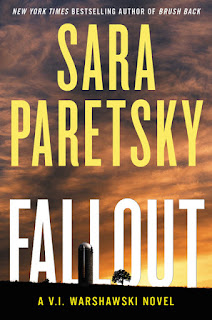

Just launched! The B-Team

They do wrong for all the right reasons, and sometimes it even works!

Available at Chapters, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and all the usual online suspects.

Is there an age at which we should stop writing novels? Philip Roth thought so. In his late seventies, he stopped writing because he felt his best books were behind him, and any future writing would be inferior. (His word.)

A colleague, Barbara Fradkin, brought this to my attention the other day, and it started a heated discussion.

Many authors have written past their prime. I can name two (P.D. James and Mary Stewart) who were favourites of mine. But their last few books weren’t all that good, in my opinion. Perhaps too long, too ponderous; plots convoluted and not as well conceived…they lacked the magic I associated with those writers. I was disappointed. And somewhat embarrassed.

What an odd reaction. I was embarrassed for my literary heroes, that they had written past their best days. And I don’t want that to happen to me.

The thing is, how will we know?

One might argue that it’s easier to know in these days with the Internet. Amazon reviewers will tell us when our work isn’t up to par. Oh boy, will they tell us.

But I want to know before that last book is released. How will I tell?

The Idea-Well

I’ve had 100 comedy credits, 40 short stories and 14 books published. I’m working on number 15. That’s 55 fiction plots already used up. A lot more, if you count the comedy. How many original plot ideas can I hope to have in my lifetime? Some might argue that there are no original plot ideas, but I look at it differently. In the case of authors who are getting published in the traditional markets, every story we manage to sell is one the publisher hasn’t seen before, in that it takes a different spin. It may be we are reusing themes, but the route an author takes to send us on that journey – the roadmap – will be different.

One day, I expect my idea-well will dry up.

The Chess Game You Can’t Win

I’m paraphrasing my colleague here, but writing a mystery is particularly complex. It usually is a matter of extreme planning. Suspects, motives, red herrings, multiple clues…a good mystery novel is perhaps the most difficult type of book to write. I liken it to a chess game. You have so many pieces on the board, they all do different things, and you have to keep track of all of them.

It gets harder as you get older. I am not yet a senior citizen, but already I am finding the demands of my current book (a detective mystery) enormous. Usually I write capers, which are shorter but equally meticulously plotted. You just don’t sit down and write these things. You plan them for weeks, and re-examine them as you go. You need to be sharp. Your memory needs to be first-rate.

My memory needs a grade A mechanic and a complete overhaul.

The Pain, the Pain

Ouch. My back hurts. I’ve been here four hours with two breaks. Not sure how I’m going to get up. It will require two hands on the desk, and legs far apart. Then a brief stretch before I can loosen the back so as not to walk like an injured chimp.

My wrists are starting to act up. Decades at the computer have given me weird repetitive stress injuries. Not just the common ones. My eyes are blurry. And then there’s my neck.

Okay, I’ll stop now. If you look at my photo, you’ll see a smiling perky gal with still-thick auburn hair. That photo lies. I may *look* like that, but…

You get the picture <sic>.

Writing is work – hard work, mentally and physically. I’m getting ready to face the day when it becomes too much work. Maybe, as I find novels more difficult to write, I’ll switch back to shorter fiction, my original love. If these short stories continue to be published by the big magazines (how I love AHMM) then I assume the great abyss is still some steps away.

But it’s getting closer.

How about you? Do you plan to write until you reach that big computer room in the sky?

Just launched! The B-Team

They do wrong for all the right reasons, and sometimes it even works!

Available at Chapters, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and all the usual online suspects.

Labels:

Amazon,

fiction,

ideas,

Mary Stewart,

P.D. James,

Philip Roth,

plots,

reviews,

writing

Location:

Oakville, ON, Canada

23 February 2018

Style and Formula in The French Connection - a guest post by Chris McGinley

by Thomas Pluck

Let me introduce Chris McGinley, a writer and reviewer whose work has appeared in Shotgun Honey, Out of the Gutter, Near to the Knuckle, and Yellow Mama. We were jawing about one of my favorite films, William Friedkin's classic The French Connection, and he had a lot to say. I thought it deserved a wider audience. --Thomas Pluck

Let me introduce Chris McGinley, a writer and reviewer whose work has appeared in Shotgun Honey, Out of the Gutter, Near to the Knuckle, and Yellow Mama. We were jawing about one of my favorite films, William Friedkin's classic The French Connection, and he had a lot to say. I thought it deserved a wider audience. --Thomas Pluck

Style and Formula in The French Connection

by Chris McGinley

Much has been written about the style and

mood of William Friedkin's The French

Connection (1971). Commentators are

fond of identifying influences ranging from Costa-Gavras' Z and the Maysles brothers work, to the more recently noted

Kartemquin documentaries of the 1960s.

There's been a great deal of talk about long takes, overlapping dialogue

and the film's "gritty" verite

style generally. What's so interesting

to me, however, is how the elements of cinematography and sound establish the

important formal elements of the police

procedural in The French Connection. The scenes unfold in a manner so completely

artful and seamless that we forget we're watching a Hollywood cop film. Indeed, what's unorthodox (and liberating)

about the film is not that it deviates significantly from the procedural

formula, but that the elements of formula are artfully hidden in its style.

The opening Marseilles scene, and the

shakedown at the Oasis bar that follows, establish some narrative basics common

to the procedural. So far, we know we're

in the gritty world of undercover narcs who will most likely encounter

something outside of their usual experience, something international, something

"big." None of this is

especially imaginative or atypical. But

the foot chase that follows the shakedown introduces a few elements unique to

the narrative. First, it initiates a

trope that works in tandem with the visual style of the film, pursuit. Yes, most

cop films involve pursuit of some sort, but pursuit in The French Connection represents something larger. In fact, for Popeye and Cloudy chase is the

heart of investigatory work. They walk,

run, drive, stake-out, ride subways, and generally tail their quarry. Such scenes occupy the bulk of the screen

time. There's precious little gun-play and virtually no tough guy talk in The French Connection. No suspect is ever braced or interviewed

formally. And when there is some

dialogue between cop and con, like at the close of the foot chase scene, the

film seems to make a point about its uselessness. (The "pick your feet in

Poughkeepsie" comment is to this day still an enigmatic remark, and the

cops get nothing important from the pusher they arrest.) But we are introduced to their singular metier: chase.

It's this element that drives the story,

again in some degree like many cop films, but in far greater quantity, and in a

manner that serves the stylistic innovation for which the film is so notable. As viewers, we never tire of the relentless

pursuit, nor do we lament the absence of any profiling, interrogation, cop

fraternity, or even the sex and romance common to so many procedurals of the

era. This is because the formal feature

of pursuit, the detective work at the heart of the film, operates in the service of the film's style, or

look. In the first twenty minutes alone,

Popeye and Cloudy follow Sal and Angie across locations in Times Square, the

Lower East Side, Little Italy, Brooklyn, and the Upper west Side. We get swept up not in the dialogue between

the cops--or in the commission of any actual crimes--but in the locales and in

the way they are presented to us, as naturalistic tableaus often filmed in hand

held shots. Actually, Doyle and Cloudy

say little to each other during this first twenty minutes. They simply follow. The locations, the neon lights, the grey

urban landscapes, and the cars and bridges together form a varied terrain that

shapes the aesthetic of the film and simultaneously serves the formal narrative

function of pursuit/detection.

Interestingly, neither Sal, Angie, nor

Joel Weinstock utters a single audible word by this point, nor have they

committed a crime. Rather, it's the

visual tableau, the film's much-noted "verite"

aesthetic, that propels the narrative, not a criminal backstory or a crime

witnessed by cops, or even a credible lead.

Initially, the cops' boss, Simonson, tells them that they "couldn't

bust a three time loser" with the weak evidence they have on Sal or

Weinstock. And though the first chase

ends in a most uneventful moment that would seem to support his assertion, Sal

and Angie stuffing the newspapers they sell into the front sections, the cops

know that the tail has paid off. It's led

to the Weinstock connection.

The varied landscapes of the film

through which the constant chase is conducted, brilliantly shot in their

natural dreariness by cinematographer Owen Roizman, should also be understood

as a formal narrative element relating to the cops' ability to pursue the criminals.

Until now, the detectives have been confined to Brooklyn, in fact to

Bedford-Stuyvesant, and so they must lobby Chief Simonson for a detachment in

order to make a plea for the case. But Simonson

is reluctant to allow the cops to go beyond their district, and he supports his

logic through chastising the cops who bring in only small time hoods and

dealers, though he concedes that they lead the department in arrests year after

year. At the risk of over-reaching here,

I propose that the expanded geographical jurisdiction, which the Chief wisely

approves in the end, serves the narrative demands of the film as much as it

does the work of Popeye and Cloudy. The

cops need to follow the chase wherever

it takes them. It's what they do:

chase. And it's the chase itself that shapes

the film's distinctive aesthetic--the under-lit interiors and the sunless and

frigid exteriors of the many locations across the city, sites that take the

cops well beyond their usual beat, to places both above and below ground.

It's also clear early on that that

non-diegetic sound is crucial to the formal elements of the procedural in The French Connection. Again, the cops don't do a whole lot of talking. Their continued pursuit of Sal, Charnier, and

Weinstock is characterized by a conspicuous lack

of dialogue, in fact. But it's the score by avant-garde jazz composer Don Ellis

that aids in creating both the tension and movement necessary to narrative

development. It all begins at The Chez,

where Popeye and Cloudy go for a drink on the night they arrest the

pusher. Here again the formal elements

of the genre, in this instance a hunch that leads to a chase, are presented

without much dialogue. Popeye tells Cloudy

he recognizes "at least two junk connections" at Sal's table. But as he locks onto his quarry, the diegetic

music of the Three Degrees' "Everybody's Going to the Moon" fades out

and Ellis' high pitched, electronic dissonance rises. We watch people talk at Sal's table, but we only

see their mouths move. This technique is

repeated in the scene where Popeye keeps tabs on Charnier while he dines at Le

Copain, and in places elsewhere where neither the viewer nor the cops are privy

to an important conversation.

Instead, it's Ellis' atonal score that

heightens the tension in so many of these scenes, creating a narrative momentum

where it wouldn't exist otherwise. For

example, consider again the scene in which the cops first follow Sal and Angie. On the

surface, it's little more than a slow speed tail scene around town. Nothing substantive really happens, and all the cops see is a

possible "drop" in Little Italy and a car switch. At one point, Cloudy nearly falls

asleep. But Ellis' baleful brass notes

and discordant passages are used to enliven the scene, to give it tension and

motion. There's a kinetic feel to it

that belies the slow speed nature of the "chase." I won't discuss in detail the several other

scenes in which the score heightens the action and supports the element of

pursuit, but it happens throughout the long tail of Charnier and company around

town, in the stakeout of the drug car, in the Ward Island scenes, and in other

places.

It's true that there are a few stock

elements of the Hollywood procedural in places, but they seem perfunctory and cliché

(almost bogus by design), and it's not at all clear how they function formally

in the film. Simonson plays the role of

the combustible chief at odds with the detectives in two separate scenes, the

second of which seems entirely unnecessary.

He removes the cops from special assignment, but there are no

repercussions to follow. Popeye is

immediately targeted by the sniper and the case simply resumes without further

comment from the Chief. (The cops never

go "rogue," as it were.) Cloudy

performs some clever detection in places, like in the scene where Devereaux's

car is examined. But such elements are

rare. No, the film constructs its formal

genre elements principally through its style, not through dialogue or the conventions

of the procedural like interviews, profiling, tough-guy talk, or even violence

(of which there is comparatively little).

Together, Ellis' avant-garde score and

Roizman's changing landscapes, themselves a sort of kinesthesis created through

editing, propel the narrative action in a way few other films have ever

done. Simply put, this is why The French Connection is so important to

the Hollywood police procedural. Its

formal elements are embodied in large part through its style, something so

rarely seen either before or since.

22 February 2018

Vancouver Author Sam Wiebe Talks About "Cut You Down"

by Brian Thornton

For today's blog entry it's my pleasure to introduce to you Vancouver crime writer Sam Wiebe. I first met Sam at the 2015 Left Coast Crime conference in Portland, Oregon. We bonded over similar tastes in literature, music and film, and have been pals ever since.. He's coming to the Seattle area next month and appearing in support of the release of a new book entitled Cut You Down.

Now, it's always nice to meet a fellow traveler who makes the same sort of "art" that you make. It's even nicer when the art that fellow traveler produces is the sort of first-rate stuff that Sam Wiebe produces. So we're not only friends, I'm also a fan. Naturally I thought it would be nice to highlight Sam and his work in a blog post in advance of his appearance here next month. He graciously agreed, and the end result you see below. My questions are in bold face.

First, a bit about Sam:

Sam Wiebe was born in Vancouver. He has held a variety of odd jobs, earned an MA in English, published Last of the Independents (2014) and Invisible Dead (2016). His latest is Cut You Down. He has published short stories in Thuglit, subTerrain and Spinetingler, in addition to collecting and editing Akashic Books' forthcoming anthology Vancouver Noir.

And now to the interview:

First, loved both your first novel, Last of the Independents, and your first Wakeland novel, Invisible Dead. Can you comment on how you changed up protagonists between your first and second novel, and let our readers in on why you had to do that?

Thanks! I look at Last of the Independents as my "demo tape." There are things about storytelling I was working out, and not to give away the ending, but that book wraps up Mike's story pretty well. The tone of Invisible Dead was a bit more complex, a bit more grounded in Vancouver history, and I wanted a protagonist who would reflect that. Dave Wakeland is younger than most private eyes--in Cut You Down he's just turned thirty. He was briefly a cop, and spent his youth boxing out of Vancouver's Astoria Gym. In some ways he's a throwback to classic PIs like Lew Archer and the Continental Op, but he's also a young guy trying to make sense of a rapidly changing city. I think of him as the flawed but beating heart of Vancouver.

In your second novel, Invisible Dead, you took what could have been just another depressing missing persons (in this instance the "missing person" being a First Nations–that's Native American for those of us reading this in the States–prostitute named Chelsea Loam) story and really worked it into a superb commentary on the human condition. I felt like we all know a Chelsea Loam, or many Chelsea Loams. And yet she's also such a cypher. How and when did this idea hook you?

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.

And it's a theme you have clearly continued to work with in your new book, Cut You Down. So tell us about this new novel of yours.

Cut You Down is the second novel about Vancouver PI Dave Wakeland. He's tasked with finding a missing college student who's mixed up in a school scandal, and who was last seen with a group of suburban gangsters. Adding to that, an ex-girlfriend, police officer Sonia Drego, asks Wakeland to check into the background of her partner, a troubled cop who's been acting strange. The book moves from a rapidly changing Vancouver, to the wilds of Washington State, to a suburban gangland where things aren't what they seem.

I was struck by the outsized role played by the city of Vancouver (and its environs) in Invisible Dead. Setting is a crucial, and all-too-often underutilized, part of fiction. So many great writers have made effective use of setting, rendering it so vivid and affecting that it frequently acts almost like an additional character in their work. Thinking of Dickens' London, Saul Bellow's Chicago, Chandler's Los Angeles, Hammett's San Francisco, David Goodis with Philadelphia, and so on. I feel like you've done a great job of channeling Vancouver in much the same way. Was this a conscious choice on your part, or did it sneak up on you?

It was conscious. A big part of that novel was the disconnect between how much I love Vancouver and how horrific some of the things that go on here are. I always liked the way Ian Rankin handled those sides of Edinburgh--the tourist side and the resident side, the rich side and the side for everybody else. Vancouver is heartbreaking in that way. Cut You Down builds on that disconnect even more, getting into gentrification and displacement, and the lengths people will go to maintain their standard of living.

And Vancouver isn't the only changeable element to this series. Wakeland himself seems far from static:. How did Wakeland change for you this go-round?

He’s forced to deal with more of his past—when his police officer ex-girlfriend asks for his help, it drags up both their relationship, and his brief career as a police officer. Trauma and violence and long buried secrets—he’s got his work cut out for him.

Writing a follow-up to a successful first book is always challenging, in ways writing that first book (a challenge of its own) aren't. Can you walk us through some of these challenges specific to Cut You Down?

Sure. Invisible Dead was a case where I knew the story early on, and the revisions honed that. It’s tighter and better than the first draft, but pretty much the same book.

With Cut You Down, there were a lot of things I discovered during the revisions. It changed drastically, and that process enriched it. For example, the suburban gangsters The Hayes Brothers were introduced late, but I love the element of menace they inject, and the fact that they mirror both Wakeland’s and Tabitha’s stories, as young people trying to make sense of a world where the rules of their parents no longer seem to apply. They’re kind of broken versions of Dave—as he says, what he might have been like if he’d had a few more advantages in life.

Music plays such a huge part in your writing. You're obviously a musician. And you're from a pretty musical family, too, right?

I was a drummer--not sure if that counts as a musician or not! My dad was a studio and club guitarist around Vancouver, playing on the Irish Rovers television show and with the Fraser MacPherson Big Band. He still plays jazz gigs around town.

You know the old joke about what the definition of a drummer is, right? “A guy who beats on stuff and hangs out with musicians”?

I think my favourite is, "How can you tell a drummer is knocking on your door? The knocking speeds up."

Reading your book called to mind the work of the great Irish writer Ken Bruen, who leavens his fiction with musical reference after musical reference, some relevant to the plot, some just shout outs to what the author considers great music. You do a fair amount of this as well. Did these references creep into your work or is this something you've consciously developed?

It's a way to add a sonic element to description, and to give a snapshot of someone's character. I also like throwing in shoutouts to bands from the Pacfic Northwest--in Cut You Down, there are references to Mad Season's Above and NoMeansNo's Small Parts Isolated and Destroyed, among others.

For those of our readers in the Puget Sound area, Sam will be appearing in our back yard in just a few weeks. He's going to read from his new novel on Monday, March 12th, 7 P.M., at Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park You can get more details here).

And that brings us to our last question: Will copies of your other books be available as well?

Third Place will be selling books, and yes, they’ll be in stock!

|

| One of Canada's Finest: Sam Wiebe |

For today's blog entry it's my pleasure to introduce to you Vancouver crime writer Sam Wiebe. I first met Sam at the 2015 Left Coast Crime conference in Portland, Oregon. We bonded over similar tastes in literature, music and film, and have been pals ever since.. He's coming to the Seattle area next month and appearing in support of the release of a new book entitled Cut You Down.

Now, it's always nice to meet a fellow traveler who makes the same sort of "art" that you make. It's even nicer when the art that fellow traveler produces is the sort of first-rate stuff that Sam Wiebe produces. So we're not only friends, I'm also a fan. Naturally I thought it would be nice to highlight Sam and his work in a blog post in advance of his appearance here next month. He graciously agreed, and the end result you see below. My questions are in bold face.

First, a bit about Sam:

Sam Wiebe was born in Vancouver. He has held a variety of odd jobs, earned an MA in English, published Last of the Independents (2014) and Invisible Dead (2016). His latest is Cut You Down. He has published short stories in Thuglit, subTerrain and Spinetingler, in addition to collecting and editing Akashic Books' forthcoming anthology Vancouver Noir.

And now to the interview:

First, loved both your first novel, Last of the Independents, and your first Wakeland novel, Invisible Dead. Can you comment on how you changed up protagonists between your first and second novel, and let our readers in on why you had to do that?

Thanks! I look at Last of the Independents as my "demo tape." There are things about storytelling I was working out, and not to give away the ending, but that book wraps up Mike's story pretty well. The tone of Invisible Dead was a bit more complex, a bit more grounded in Vancouver history, and I wanted a protagonist who would reflect that. Dave Wakeland is younger than most private eyes--in Cut You Down he's just turned thirty. He was briefly a cop, and spent his youth boxing out of Vancouver's Astoria Gym. In some ways he's a throwback to classic PIs like Lew Archer and the Continental Op, but he's also a young guy trying to make sense of a rapidly changing city. I think of him as the flawed but beating heart of Vancouver.

In your second novel, Invisible Dead, you took what could have been just another depressing missing persons (in this instance the "missing person" being a First Nations–that's Native American for those of us reading this in the States–prostitute named Chelsea Loam) story and really worked it into a superb commentary on the human condition. I felt like we all know a Chelsea Loam, or many Chelsea Loams. And yet she's also such a cypher. How and when did this idea hook you?

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.And it's a theme you have clearly continued to work with in your new book, Cut You Down. So tell us about this new novel of yours.

Cut You Down is the second novel about Vancouver PI Dave Wakeland. He's tasked with finding a missing college student who's mixed up in a school scandal, and who was last seen with a group of suburban gangsters. Adding to that, an ex-girlfriend, police officer Sonia Drego, asks Wakeland to check into the background of her partner, a troubled cop who's been acting strange. The book moves from a rapidly changing Vancouver, to the wilds of Washington State, to a suburban gangland where things aren't what they seem.

I was struck by the outsized role played by the city of Vancouver (and its environs) in Invisible Dead. Setting is a crucial, and all-too-often underutilized, part of fiction. So many great writers have made effective use of setting, rendering it so vivid and affecting that it frequently acts almost like an additional character in their work. Thinking of Dickens' London, Saul Bellow's Chicago, Chandler's Los Angeles, Hammett's San Francisco, David Goodis with Philadelphia, and so on. I feel like you've done a great job of channeling Vancouver in much the same way. Was this a conscious choice on your part, or did it sneak up on you?

It was conscious. A big part of that novel was the disconnect between how much I love Vancouver and how horrific some of the things that go on here are. I always liked the way Ian Rankin handled those sides of Edinburgh--the tourist side and the resident side, the rich side and the side for everybody else. Vancouver is heartbreaking in that way. Cut You Down builds on that disconnect even more, getting into gentrification and displacement, and the lengths people will go to maintain their standard of living.

And Vancouver isn't the only changeable element to this series. Wakeland himself seems far from static:. How did Wakeland change for you this go-round?

He’s forced to deal with more of his past—when his police officer ex-girlfriend asks for his help, it drags up both their relationship, and his brief career as a police officer. Trauma and violence and long buried secrets—he’s got his work cut out for him.

Writing a follow-up to a successful first book is always challenging, in ways writing that first book (a challenge of its own) aren't. Can you walk us through some of these challenges specific to Cut You Down?

Sure. Invisible Dead was a case where I knew the story early on, and the revisions honed that. It’s tighter and better than the first draft, but pretty much the same book.

With Cut You Down, there were a lot of things I discovered during the revisions. It changed drastically, and that process enriched it. For example, the suburban gangsters The Hayes Brothers were introduced late, but I love the element of menace they inject, and the fact that they mirror both Wakeland’s and Tabitha’s stories, as young people trying to make sense of a world where the rules of their parents no longer seem to apply. They’re kind of broken versions of Dave—as he says, what he might have been like if he’d had a few more advantages in life.

Music plays such a huge part in your writing. You're obviously a musician. And you're from a pretty musical family, too, right?

I was a drummer--not sure if that counts as a musician or not! My dad was a studio and club guitarist around Vancouver, playing on the Irish Rovers television show and with the Fraser MacPherson Big Band. He still plays jazz gigs around town.

You know the old joke about what the definition of a drummer is, right? “A guy who beats on stuff and hangs out with musicians”?

I think my favourite is, "How can you tell a drummer is knocking on your door? The knocking speeds up."

Reading your book called to mind the work of the great Irish writer Ken Bruen, who leavens his fiction with musical reference after musical reference, some relevant to the plot, some just shout outs to what the author considers great music. You do a fair amount of this as well. Did these references creep into your work or is this something you've consciously developed?

It's a way to add a sonic element to description, and to give a snapshot of someone's character. I also like throwing in shoutouts to bands from the Pacfic Northwest--in Cut You Down, there are references to Mad Season's Above and NoMeansNo's Small Parts Isolated and Destroyed, among others.

For those of our readers in the Puget Sound area, Sam will be appearing in our back yard in just a few weeks. He's going to read from his new novel on Monday, March 12th, 7 P.M., at Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park You can get more details here).

And that brings us to our last question: Will copies of your other books be available as well?

Third Place will be selling books, and yes, they’ll be in stock!

21 February 2018

There Was A Wicked Messenger

by Robert Lopresti

I have lots of friends on FaceBook, some of them I have known since childhood and some I wouldn't know if they bit me. That's the nature of FB.

Not long ago one of that latter group contacted me on the FaceBook app called Messenger. It became pretty clear that something shifty was going on and, checking out that friend's FB page I found a note saying "Ignore any messages from him. His account has been hacked." Well, by then I was too interested to ignore them.

Alas, I didn't spot the typos here. (I was in a restaurant wating for lunch to arrive.) I meant to say "I enjoyed their singing but frankly their dancework..."

??? indeed.

At that point I gave up. But if I had sent one more message it would have gone something like this:

I contacted the sponsors and they said they left the names of some winners on the list at the request of the FBI. You see, it turns out some real scumbags are trying to rip off the winners. I hate people like that, don't you? How do they spend all day trying to rob people who never did them any harm and then use those same hands to caress their lovers or comfort their children? How do they talk to their mothers knowing how ashamed those mothers would be if they knew the truth about them? Please be careful, my friend. There is a lot of evil out there.

By the way, a few days after this happened to me the same thing happened to Neil Steinberg, one of my favorite columnists. You can read about what he did here.

I have lots of friends on FaceBook, some of them I have known since childhood and some I wouldn't know if they bit me. That's the nature of FB.

Not long ago one of that latter group contacted me on the FaceBook app called Messenger. It became pretty clear that something shifty was going on and, checking out that friend's FB page I found a note saying "Ignore any messages from him. His account has been hacked." Well, by then I was too interested to ignore them.

Alas, I didn't spot the typos here. (I was in a restaurant wating for lunch to arrive.) I meant to say "I enjoyed their singing but frankly their dancework..."

??? indeed.

At that point I gave up. But if I had sent one more message it would have gone something like this:

I contacted the sponsors and they said they left the names of some winners on the list at the request of the FBI. You see, it turns out some real scumbags are trying to rip off the winners. I hate people like that, don't you? How do they spend all day trying to rob people who never did them any harm and then use those same hands to caress their lovers or comfort their children? How do they talk to their mothers knowing how ashamed those mothers would be if they knew the truth about them? Please be careful, my friend. There is a lot of evil out there.

By the way, a few days after this happened to me the same thing happened to Neil Steinberg, one of my favorite columnists. You can read about what he did here.

20 February 2018

Make Them Suffer--If You Can

by Barb Goffman

Authors in the mystery community are generally known for being nice folks. Helpful, welcoming, even pleasant. But when it comes to their work, successful writers are mean. They have to be.

An author who likes her characters too much might be inclined to make things easy for them. The sleuth quickly finds the killer. She's never in any real danger. In fact, there's no murder at all in the story or book. Just an attempted murder, but the sleuth's best friend pulls through just fine.

These scenarios may be all well and good in Happily Ever After Land. But in Crime Land, they result in a book without tension that's probably going to be way too short. That's why editors often tell mystery authors to make their characters suffer.

Yet that can be easier said than done. If you're basing a character on someone you don't like, then you might have a grand time writing every punch, broken bone, and funeral. But not every character can be based on an enemy. And sometimes characters seem to plead from the page, "Don't do that to me."

It's happened to me. I started writing a certain story a few weeks ago. I had a great first page, and then I got stuck. No matter how I tried to write the next several sentences, they didn't work right. I walked away from the computer. Sometimes I find a break can help a writing logjam. But not this time. In the end, I found I simply couldn't write the story I'd planned because, you see, that plan had included the death of a cat. And I just couldn't do it.

The publication I was aiming the story for would have been fine with a story that included a dead animal. But I wasn't fine with it. And I knew my regular readers wouldn't like it either. Sure animals die in real life, and sometimes they die in fiction too. But those deaths should be key to the story. The Yearling wouldn't work if the deer didn't die. And Old Yeller needed the dog to die too.

I'm going to refer back to these very points if and when another story I've written involving animal jeopardy gets published. Sometimes that jeopardy is necessary for the story. And that's the key question: is it necessary? In the story I was writing about the cat it wasn't, and I knew it in my gut, even if I didn't know it in my head at first. That's why I couldn't bring myself to write the story as planned. Instead, with the help of a friend, I found another way to make the story work, one without any harm to animals.

It's not the first time something like that has happened to me. About six years ago I wrote a story called "Suffer the Little Children" (published in my collection, Don't Get Mad, Get Even). This is the first story of mine involving a female sheriff name Ellen Wescott. She's smart and honest and way different than I'd planned. Originally she was supposed to be a corrupt man. But as I was thinking through the plot during my planning stage, I heard that male sheriff say in my head, "Don't make me do that. I don't want to do that." Spooky, right?

While part of me immediately responded, "too bad,"--he had to suffer--another part of me knew that when characters talk back like that, it's because my subconscious knows what I'm planning isn't going to work. Either it won't work for the readers, as with the cat I couldn't kill. Or it won't work for the plot, as was the case with this sheriff story. So my corrupt male sheriff became an honorable female sheriff, and large parts of the plot changed. My female sheriff faced obstacles, but she was a good person. That was a compromise my gut could live with.