|

| Sara Paretsky © Steven Gross |

In 1986, I read the first V I Warshawski private eye book, Indemnity Only. I also was writing a female P.I. novel when I learned women mystery writers at Bouchercon were meeting and forming a group called Sisters In Crime. One major objective of SinC was to raise publishing and public awareness of women mystery writers. This organization was the brainchild of V I Warshawski’s author, Sara Paretsky.

In 1988, I attended my first Edgars and Bouchercon. I quickly learned Sara was passionate about women writers getting a fair shake.

In 1990, my husband and I opened a mystery bookstore in Austin. Three years later, we hosted a mystery convention, Southwest Mystery Con. A small group of Austin mystery women formed a chapter we named Heart of Texas Sisters in Crime. Through that, Sara and I became friends. I’m proud our H•O•T chapter of SinC still meets monthly. I’m proud that Sara still fights for women mystery writers. And I’m honored to introduce Sara as today’s guest writer.

Sara Paretsky and her acclaimed P I, V I Warshawski, transformed the role of women in contemporary crime fiction, beginning with the publication of her first novel, Indemnity Only, in 1982. Sisters-in-Crime, the advocacy organization she founded in 1986, has helped a new generation of crime writers and fighters to thrive.

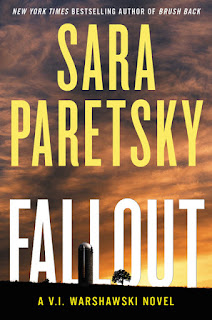

Among other awards, Paretsky holds the Cartier Diamond Dagger, MWA's Grand Master, and Ms. Magazine's Woman of the Year. Her PhD dissertation on 19th-Century US Intellectual History was recently published by the University of Chicago Press. Her most recent novel is Fallout, Harper-Collins 2017. Visit her at SaraParetsky.com

— Jan Grape

Why I Write

by Sara Paretsky

by Sara Paretsky

Years ago, when I was in my twenties, I heard an interview with the composer Aaron Copland. The interviewer asked why it had been over a decade since Copland's last completed composition. I thought the question was insensitive but Copland's answer frightened me: "Songs stopped coming to me," he said.

I wasn't a published writer at the time, but I was a lifelong writer of stories and poems. These were a private exploration of an interior landscape. My earliest memories include the stories that came to me when I was a small child. The thought that these might stop ("as if someone turned off a faucet," Copland also said) seems as terrifying to me today as it did all fifty years back.

I write because stories come to me. I love language, I love playing with words and rewriting and reworking, trying to polish, trying to explore new narrative strategies, but I write stories, not words. Many times the stories I tell in my head aren't things I ever actually put onto a page. Instead, I'm rehearsing dramas that help me understand myself, why I act the way I do, whether it's even possible for me to do things differently. Where some people turn to abstract philosophy or religion to answer such questions, for me it's narrative, it's fiction, that helps sort out moral or personal issues.

At night, I often tell myself a bedtime story- not a good activity for a chronic insomniac, by the way: the emotions become too intense for rest. When I was a child and an adolescent, the bedtime stories were versions of my wishes. They usually depicted safe and magical places. I was never a hero in my adventures; I was someone escaping into safety.

As a young adult, I imagined myself as a published writer. For many years, the story I told myself was of becoming a writer. Over a period of eight years, that imagined scenario slowly made me strong enough to try to write for publication. After V I Warshawski came into my life, my private narratives changed again. I don't lie in bed thinking about V I; I'm imagining other kinds of drama, but these often form the subtext of the V I narratives.

I'm always running three or four storylines: the private ones, and the ones I'm trying to turn into novels. I need both kinds going side by side to keep me writing.

Storylines are suggested by many things- people I meet, books I'm reading, news stories I'm following- but the stories themselves come from a place whose location I don't really know. I imagine it as an aquifer, some inky underground reservoir that feeds writers and painters and musicians and anyone else doing creative work. It's a lake so deep that no one who drinks from it, not even Shakespeare, not Mozart or Archimedes, ever gets to the bottom.

There have been times when, in Copland's phrase, the faucet's been turned off; my entry to the aquifer has been shut down. No stories arrive and I panic, wondering if this is it, the last story I'll ever get, as Copland found himself with the last song. If that ever happens permanently, I don't know what I'll do.

So far, each time, the spigot has miraculously been turned on again; the stories come back, I start writing once more. Each time it happens, though, I return to work with an awareness that I've been given a gift that can vanish like a lake in a drought.

Such a great essay! Thanks for sharing this, Jan!

ReplyDeleteI certainly can agree that stories are mysterious gifts and their continuance is always in doubt.

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing this, Jan. I always like seeing how other writers come to where they're at and their process or thoughts on writing.

ReplyDeleteGreat column! Thanks, Jan.

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing this, Jan!

ReplyDeleteYes, that's my fear too. That the stories won't come anymore. When that happens (if it does) I hope I'll be content with the body of work I have behind me.

ReplyDeleteBody. Of work. I like that. A body of work by a crime writer. Why did I never think of that before?

THanks to Sara and Jan. Very good essay. Every blank screen is a little bit scary...

ReplyDeleteSome favorite authors seem to have only one book in them, the great Harper Lee for example. Literature has its parallels in music, as you pointed out with Copland. Billy Joel abruptly stopped writing, saying he was coming up dry and no one would want to listen to the dregs. Bobby Dylan revealed he’d run out of words, which had profoundly shaken him.

ReplyDeleteFortunately Sara, you’ve pounded out story after story. I read the first V I Warshawski novels in the latter 1980s and kept on reading, the crime novels where ‘Vic’ means something else entirely.

I have a confession… the vast majority of mystery writers I read are women authors. I’ve read every one of my female colleagues and love their work. I’m crushed I’ll never read another B K Stevens story. I also love Ellis Peters, Elizabeth Peters, and I wouldn’t mind if Lindsey Davis adopted me.

When it comes to Sisters in Crime, we should mention (a) they have an on-line group and (b) guys can join SinC too… been there, done that.

Melodie– what a great idea!

Sara and Jan, thanks! Loved it!

ReplyDeleteThanks everyone and a huge thanks to Sara. It is scary to lose your words. I know because I lost mine after my husband passed away. He was my first readwr, helper and muse. I'm only saying this bcause y'all might know how and why it can happen. I will say Sleuthsayers has helped me. I did write a couple of fairly decent short stories that were published. But my police woman character, Zoe Barrow, has stopped talking to me. I think and hope she will start again one day.

ReplyDelete