A quick explanation: my title implies that this is an instructional piece, but it's not. My plan today is to tell you a little about how I approach marketing my writing, and to--more importantly--ask you what your approach is. So this is actually sort of a fishing expedition. Besides, I once heard some good advice about teaching and mentoring. I was told that good instructors don't say "This is how you do it"; good instructors say "This is how I do it," and then let the student take it from there. Not everything works the same way for everybody.

Another qualification: this is a discussion about marketing short stories, not novels. Most of us here at SleuthSayers have written both, but my expertise (if I have any at all, which I often doubt) is in the area of shorts rather than longs.

Given those clarifications, here are a few random notes on the topic of selling what you've written.

Beating the bushes

Question: How do you go about finding markets for your stories?

The latest and greatest

I usually submit my new mystery stories to one of four places, first. They are The Strand Magazine, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, and Woman's World. How do I decide which? That's usually based on either content or length, or both. The Strand prefers stories of between 2000 and 6000 words; EQMM will consider stories up to 12K; AHMM will also take submissions of up to 12K, and seems to be more receptive than EQ to occasional stories with paranormal elements; and WW wants 700-word mysteries featuring a "solve-it-yourself" interactive format.

Another good print (and paying) market is Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, and I've sold several mysteries to a Colorado publication called Prairie Times (which also pays). Online markets (e-zines) include Over My Dead Body, Mysterical-E, Kings River Life, and Orchard Press Mysteries. OMDB is a paying market, Myst-E and KRL are not, and I'm not sure about OPM. There are certainly others I haven't mentioned--if any of you have favorite markets for mysteries, I'd like to hear about them.

The other two possibilities for short stories are anthologies and collections. The already-mentioned ralan.com features a number of current anthologies, and there are many more that are associated with organizations, writers' groups, charities, etc. (Anthologies also often seek reprints, which can be handy.) Collections are, well, collections--of one author's stories rather than those of a group of writers.

Submission accomplished

The way you submit a fiction manuscript is determined from the writer's guidelines for that market, and it's usually done in one of three ways:

- Snailmail. It seems a little out-of-place in this day and age, but some short story markets, including AHMM, still require submissions via regular mail, along with the cover letters and postage and envelopes that have to accompany them. A disadvantage of this method, besides the time and expense, is that responses sometimes seem to take longer.

- Submission via the publication's website. A growing number of markets (EQMM is one) now allow fiction subs via an online "form." You just (1) enter your name and the title of your story, (2) type a cover letter into the appropriate box, (3) browse and select the computer file containing your manuscript, and (4) click SUBMIT. A good thing about website submissions is that you can then check the status of your manuscript (received, rejected, accepted) online, at any time.

- E-mail. Sending your stories this way involves one of two approaches: (1) attaching the manuscript or (2) copy/pasting the text of the story into the body of the e-mail. The first is the easier--you just type your cover letter into the e-mail and then attach the manuscript's file. NOTE: When e-mailing a story I always use the word "submission" somewhere in the subject line, whether I'm told to or not.

The care and feeding of editors

There are a few rules of thumb on this subject, and I think they're mostly just common sense:

- Don't contact editors via phone. Stick to snailmail or e-mail.

- Don't contact editors via phone. Stick to snailmail or e-mail.

- Don't pester them unnecessarily.

- Don't include anything in your cover letter that's not relevant.

- Don't staple your manuscript.

- Don't tell them where your manuscript has been rejected.

- Don't tell them where your manuscript has been rejected.

- Don't use uncommon fonts (Courier and Times New Roman seem to be the standards).

- Don't put a copyright notice on your manuscript.

- Don't use a font size of less than 12-point.

- Don't divulge your Social Security number until/unless your story's accepted.

The Hints & Tips file

A few pointers, for anyone who might find them useful:

To prevent spacing and formatting errors when copy/pasting a manuscript into the body of an e-mail: (1) take out any special characters like italics--you can substitute an underscore before and after the text to indicate italics, (2) single-space your story with no indentions and with double-spacing between paragraphs, (3) save the story as a .txt file, (4) close the file, (5) open the file again--it will now be in Courier 10-point font--and (6) copy/paste the newly formatted manuscript into your e-mail after the cover letter. To be absolutely certain everything looks right, you can always e-mail it to yourself first.

I don't use an editor's first name until after he or she contacts me and either (1) uses his or her first name or (2) addresses me by my first name. After that, we're on a more casual basis forever, but until that time it's Dear Mr. Smith or Dear Ms. Jones. And if I don't yet know for sure if an editor is male or female, I play it safe and use the full name in salutations: Dear Pat Jones, Dear Lee Smith.

I used to fold shorter stories (less than five pages, say) in thirds and mail them in #10 business envelopes, but lately I've been submitting my snailmailed manuscripts flat and paper-clipped in a 9 x 12 envelope, no matter what the length. (For stories of more than 25 pages I use a butterfly clip instead.) Editors have told me they hate folded manuscripts, and--believe me--I want to make reading my stories as easy for them as possible.

More observations, more questions

- E-mailed submissions and online plug-it-into-the-box-at-the-website submissions are easy and economical, but I suspect that those processes (because they're easy) have led to a higher number of submissions to those publications. Even though snailmailed subs are a lot of trouble (and expensive, if you do enough of them), there are those writers who say it might actually be an advantage, since it probably means less competition. Once again, though, this isn't a decision the writer makes--it's usually dictated by the publication.

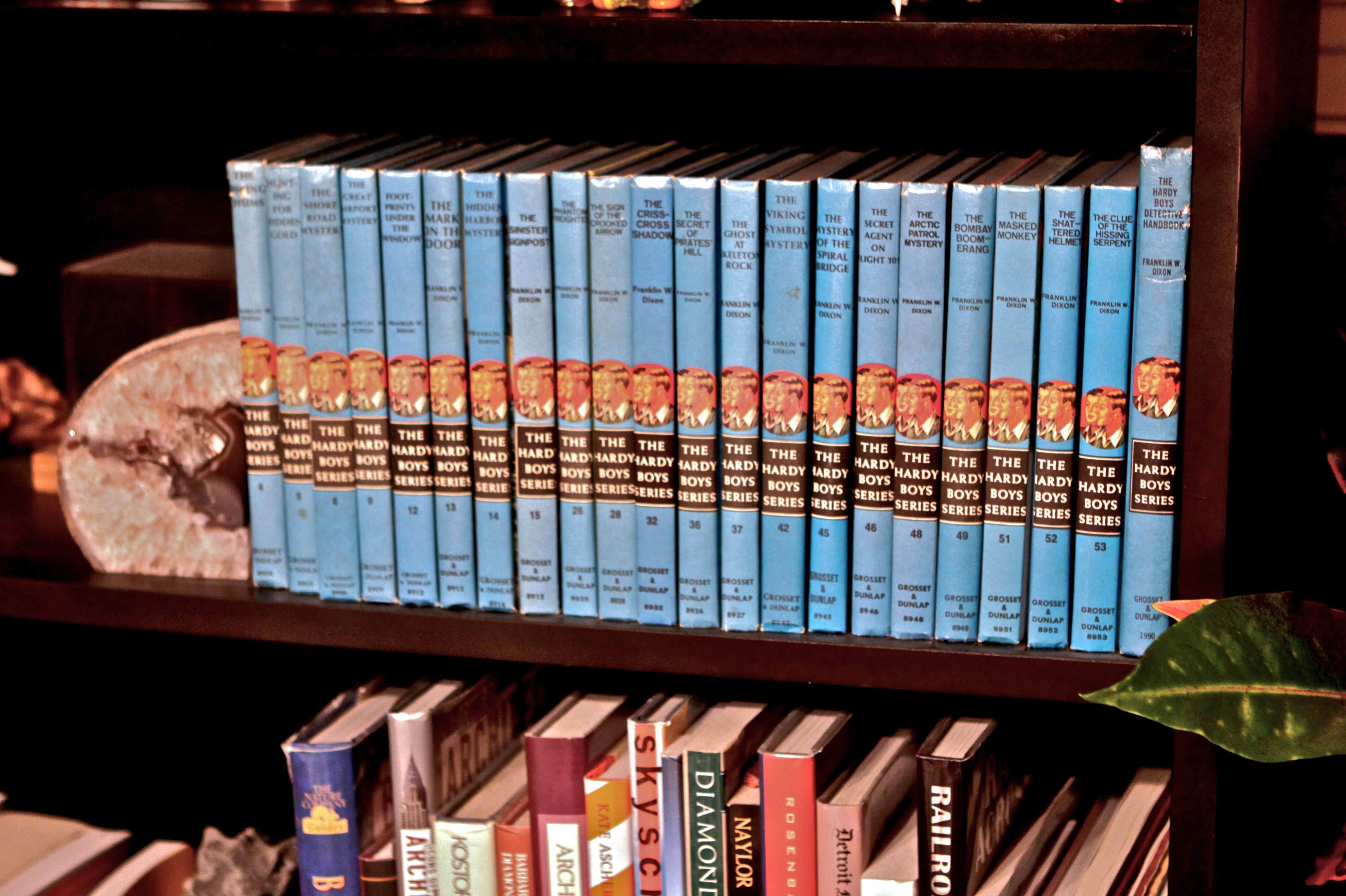

- Would you ever consider collecting your unpublished stories into a book? So far I have chosen not to. Only two of my 130 stories collected in my four books were originals--the rest were previously published. Not only did that allow me to get double duty (and double payment, I suppose) out of those stories, my publisher said he felt more comfortable with that approach because it was less of a financial risk for him: each of the stories had already been "vetted" and accepted someplace by at least one editor.

- I've not yet waded very deeply into the e-book/e-story marketplace. I have a couple of stories at Untreed Reads (a mystery and a western), I had twenty or so stories at Amazon Shorts a few years ago, and my most recent two books are available via Kindle, but otherwise I've concentrated more on print markets and--to a lesser degree--e-zines. I'd love to hear the opinions of those who have tested the e-waters.

- I'm sort of middle-of-the-road on simultaneous submissions. I recognize that the best way to get published faster is to send the same story to different markets at the same time, but I also know I don't want the (admittedly remote) possibility of two places accepting first rights to one of my stories. That not only puts egg on your face, it can put a black mark beside your name forever, on some editor's list--and all these editors know each other, by the way. I've heard some writers and writing teachers say you should ignore the "no simultaneous submissions" request/demand that many pubs put in their guidelines because the editors expect you to simultaneously submit anyway, but I think it's a little risky. No one wants to suddenly find out he has two dates for the dance and then have to tell one of them, "Sorry, but I've already asked this other girl, and . . ." How do you feel about this issue?

In closing . . .

Proof of my persistence: A few days ago I submitted eight mysteries and one sci-fi story to six different markets. And this month I've sold new stories to both Woman's World and The Saturday Evening Post. The main thing is, keep reading, keep writing, and keep submitting.

When someone tells me there's a lot of attrition among writers, I just say "Then don't get attritted."

When someone tells me there's a lot of attrition among writers, I just say "Then don't get attritted."

I'm pedalling as fast as I can.