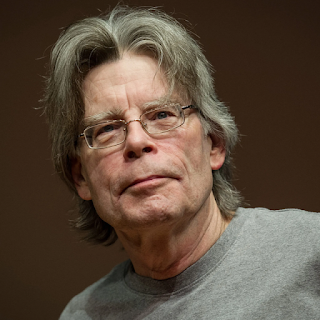

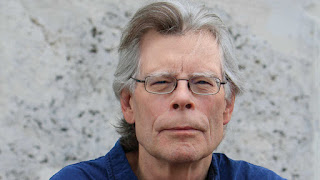

I spent 15 years going through Stephen King's canon, skipping a few screenplays and Faithful, as I am not invested enough in the two baseball teams I grew up on, let alone the Red Sox. Why so long? For starters, life. I got divorced twice during this process, I changed jobs three times in that period of my life. My current wife had a catastrophic health crisis a few years ago. And, dude, I write. I may not sell much, but I write. Also, King writes. A lot. Sixty-five novels and novellas, plus two hundred short stories. And he's still writing.

But now that we're down to a leisurely 1-3 books a year by Maine's most celebrated writer, whose canon am I going through now?

That would be one Samuel Langhorne Clemens from Hannibal, MO, and later of Hartford, CT. AKA Mark Twain. One of my first buys on Kindle was a collection of all his novels, short stories, and essays. I focused on the books. I also began reading in earnest when I read his massive and deliberately chaotic autobiography. I just now finished the books. I still have the short stories and essays to go through and bought three print books: Letters from Hawaii (compiled by his request after his death by Albert Bigelow, his editor and responsible for the earliest and shortest iteration of his autobiography), The Complete Essays of Mark Twain, and Short Stories and Tall Tales. These last three I will read in the new year.

So how was reading Twain different from King? Well, for starters, horror isn't Twain's bag. He can write a scary story, but that's not what he's about. Also, King seems embarrassed to do non-fiction. Twain shines at it. I find his travelogues much more interesting than his novels. Yes, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn are brilliant and the classics they deserve to be. But Recollections of Joan of Arc is actually better. And the later novels, a pair of Tom Sawyer sequels clearly written for a quick buck and A Horse's Tale, aren't quite as good. Twain, like any writer, is at his best when he wants to. That's probably why the three volume brick stack that is his autobiography is so readable. It's disjointed, so you can pretty much pick up anywhere, and it's your favorite uncle spinning stories. And even when Huck narrates, which he does in dialect, there's no character voice. It's Twain telling the story.

But the essays, many of which are in early form in the autobiography, are Twain's bread and butter. Twain left home and became a reporter. If he were around today, he'd have a travel blog (and no doubt a YouTube channel: Sammy C Travels the World.) It's what makes Old Times of the Mississippi, A Tramp Abroad, and Following the Equator so engaging.

The shorts, of course, play right into this. I tried to read Mark Twain's Library of Humor, which featured many humorists of his time. I wasn't laughing. One can say it was the product of the times, but that doesn't obligate me to like what the others wrote. I also find Boston-area puritan preacher Jonathan Edwards unreadable, and I was forced to study him in high school. (Hawthorne pretty much made a career out of skewering that culture.) It was the times he wrote.

I read Twain in parallel with King before I focused on finishing his canon. Unlike King, there have been no new Twain stories or works since Volume III of his autobiography debuted in 2015. So while King has work in the pipeline (and probably will not slow down should he die soon), Twain is pretty much complete.

So, who's replacing Twain as the author whose canon I'm working through? I'm about halfway through William Shakespeare. So once I've read the short stories, I'll be averaging a play a month. However, as someone recently commented in my post about The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare is meant to be watched, not read. (The sonnets notwithstanding.) So, in 2025, I plan to watch one Shakespeare play a week, which will take less than a year.