|

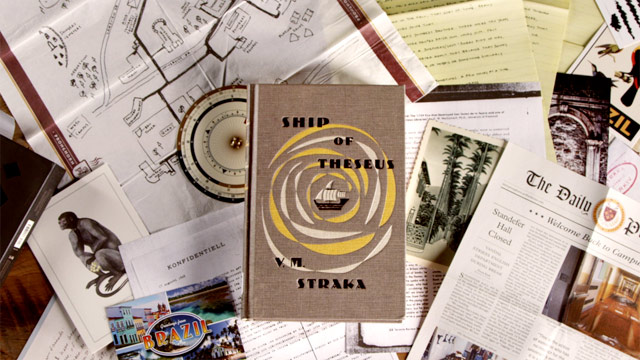

| Colin Wilson at work at his home in England |

[T]he basic impulse behind existentialism is optimistic, very much like the impulse behind all science. Existentialism is romanticism, and romanticism is the feeling that man is not the mere he has always taken himself for. Romanticism began as a tremendous surge of optimism about the stature of man. its aim — like that of science — was to raise man above the muddled feelings and impulses of his everyday humanity, and to make him a god-like observer of human existence.

Colin Wilson

Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966)

Man’s capacity to doubt is his greatest dignity.

Colin Wilson

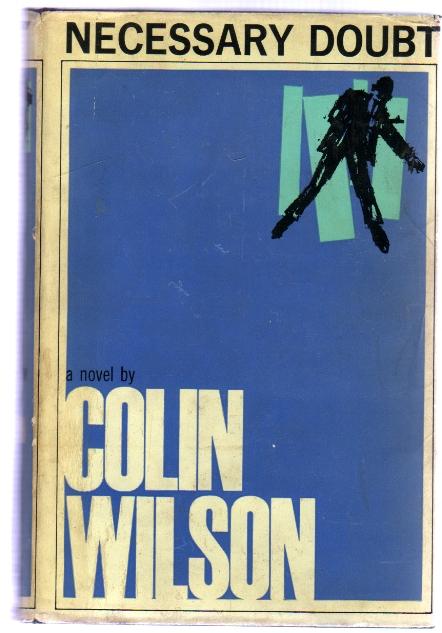

Necessary Doubt (1964)

Doubt is not the opposite of faith; it is one element of faith.

Paul Tillich, Theologian

Systematic Theology (Vol. 2, 1957)

On December 5, 2013 author Colin Wilson died in his native England.

Collin Wilson was an enigma -- one of the most prolific and yet least-known authors of our time. Wilson burst into literary prominence in 1956 with his book The Outsider, the introduction to his “new existentialism,” written in longhand by Wilson at a table in the British Museum at a time when he was living in a sleeping bag on the streets of London. The book was heralded by critics as a seminal work and the author, a mere 24, was famous. Over 100 books later, at the age of 82, Wilson died in what some would view as literary obscurity. His death went almost completely unnoticed in the United States. I am unaware of a single obituary that ran this side of the Atlantic.

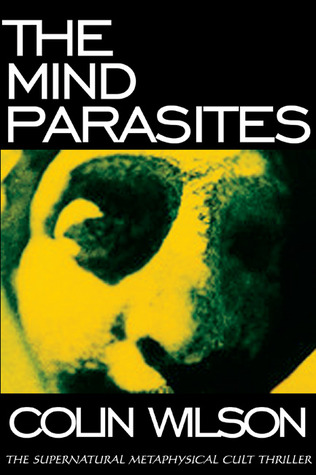

Wilson wrote his 100-odd books during a career that spanned nearly 60 years. And it is hard to imagine an author who mastered and wrote in more genres than Wilson. His works include a multi-volume series on his “new existentialism” that followed publication of The Outsider. But his work also encompasses science fiction novels, including the 1967 cult classic The Mind Parasites, biographies of historical figures as disparate as George Bernard Shaw and Abraham Maslow, and in-depth analyses of murder, sexuality, the Lost City of Atlantis, mysticism, and the occult, to mention but a few. While the genres of Wilson’s works defy any general characterization, there is a shared theme. Whether Colin Wilson was writing non-fiction or fiction his works uniformly provided a vehicle for Wilson to share his views on humanity and the power of human intellect to pull each of us up by our own bootstraps. Each of his books had a message; the take-away for the reader was the growing understanding of Wilson’s life view.

Colin Wilson also wrote mysteries, which I devoured. But that is not where I first encountered his works. That story reaches back 45 years.

1969 was a strange year for many reasons. It was not so much a watershed year -- that was 1968 -- but it had the crazy momentum of the first year that followed the 1968 watershed. During 1969 I was a student at George Washington University in downtown Washington, D.C. Ground zero in the anti-war movement. 1969 was a year that inexorably pushed everyone toward extremes: love it or leave it; change it or lose it. I remember participating in anti-war marches in front of the Nixon White House when members of my fraternity, who were also members of the National Guard, were lined up along the sidewalks with rifles, not trained on me, but still ready, as I marched past them. It was a time to draw lines. Either; or.

1969 was also a strange year on a much more personal level. In the Spring my roommate David Schlachter began experiencing increasingly bad headaches. For weeks he brushed these off. We were young at a time when youth had never seemed younger or more powerful. But eventually ignoring was no longer possible. David began to see double. He was diagnosed with a brain tumor, given (“given,” what a strange word) scant months to live.

I was away for a long weekend when David was diagnosed. Another friend, Frank DeMarco, had access to his uncle’s beach house in Avalon, New Jersey. And that’s where we were. We received the news about David upon our return.

About the same time Frank stumbled onto The Mind Parasites by Colin Wilson. He knew nothing about Wilson but, for whatever reason, was tempted by the book’s cover when he saw it for sale in a drug store. Frank was transfixed by the book, which is a clever (Wilson was always clever) science fiction send-up (and pastiche) that walks an amazingly thin line between parodying and worshiping the works of H.P. Lovecraft. Like all of Wilson's works, the book is also more than just "that science fiction story." It is a story told in the trappings of Wilson’s philosophy of life, a philosophy of human enlightenment, of the powers of the mind over the failings of the body.

What more opportune time to discover Wilson than at this juncture -- when Frank and I were each starkly confronting the perils facing our friend?

Frank recommended the book to me and I read and liked it. But for Frank the book’s message was, I think, more. It was transformational. At a time when we were grappling with the imminent death of a mutual friend a story that offered up a philosophy of transcendence, a path to spiritual powers that were not bound by the mortal limits of flesh and bone, was seductive.

I began visiting the library and checking out other Colin Wilson’s books. And while The Mind Parasites did not grab me as tenaciously as it had Frank, the Colin Wilson book that did was Necessary Doubt.

No surprise, Necessary Doubt is a mystery. But, like The Mind Parasites, it is also more. The protagonist (and detective) is a theologian, Zweig, who is modeled after the real-life theologian Paul Tillich. This appealed to me. I was minoring in religious studies and already admired Tillich, a theologian who stood somewhat “existentially” aside from his church -- somewhat of an outsider, looking in. One of Tillich’s (and Zweig’s) philosophical tenets was that to truly believe something one must first doubt it and then explore the factors that underlie that doubt. In effect, Tillich (and Zweig) argue, belief can be found only at the top of a step ladder of doubt. Zweig approaches the mystery in Necessary Doubt as would Tillich -- doubting each step, each conclusion, doubting always until convinced.

David, a senior when he was diagnosed, managed to graduate from George Washington University and returned to his parents’ home in Clarinda, Iowa. Months later, back in Washington, D.C., in February of 1970, we received a late night call telling us that David was hospitalized and not likely to survive the night. With little thought (and even less money) Frank and I walked out of our fraternity house shortly after hanging up the phone, got into Frank’s car and headed west. We were convinced (and we were right) that David would wait for us before taking his leave.

What followed was a surreal 20 hour drive from Washington, D.C. to Clarinda, Iowa. Like all surreal experiences it is hard to remember precisely what went on in that car but a lot of it involved Colin Wilson and searching the AM bandwidth for Simon and Garfunkel's Bridge Over Troubled Waters.

In The Mind Parasites the protagonist discovers, and then embraces, a life view that the mind is capable of nearly everything, and that life never really ends, in other words the belief

that the mind is beyond the accidents of the body, that it is somehow eternal and free; that the body may be trivial and particular, but the mind is universal and general. This attitude makes the mind an eternal spectator, beyond fear.

Frank and I were with David when he died early on March 2, 1970. The days that we were together on that awful winter journey Frank and I pondered -- perhaps the better word is debated -- life. The sacred and the profane. Do we each carry the spark of sacred immortality, the ability to transcend flesh and bone, or are we simply profane electric mud? And these discussions, at base, involved a mutual examination of Colin Wilson’s views, as expressed in his fiction as well as his non-fiction. We were pretty much Colin Wilson neophytes at that stage, and I pretty much remained so. But not Frank. Frank went on to seek out, and then meet Wilson, and the two knew each other, and were friends, for the rest of Wilson’s life.

Frank has recounted his discovery of Colin Wilson and has written about that trip of ours to and from Iowa in his book Muddy Tracks: Exploring an Unsuspected Reality. I occasionally pop up in the book, but you will have to watch carefully -- I’m an unnamed character. Traveling incognito. Here is Frank, in chapter one, describing, in the third person, his 1970 Colin Wilson epiphany:

Colin Wilson's books gave him an opening he could believe in: the development of mental powers! The achievement of supernatural abilities, paranormal skills! He didn't know whether he could believe in them or not, but here was a writer who was investigating reports of such things, and doing so from a point of view quite similar to his own: open and inquiring, yet skeptical and wanting to make sense of it all, rather than merely accepting someone's word for it.

In a world of full circles, the foreword to Frank’s book was written by none other than Colin Wilson. Here is part of what Wilson himself said about Frank’s transformative experiences that winter 44 years ago:

My own work had played a part in [Frank DeMarco’s] development (as [he] described in the first chapter), which is how I come to be writing this introduction. It helped to crystallize his own feeling that there is something oddly wrong with “this life,” and that there has to be some alternative, some other way.

Frank may chime in on his own here. He's an in internet presence, has his own blog, and has continued to write extensively there about Colin Wilson. As for me, I often reflect on that February trip, 44 years ago. The philosophical perspectives of Colin Wilson obviously spoke deeply to Frank in a life changing way, and from the works of Wilson and the experience of our friend’s death, 44 years ago last Sunday, Frank, I think, found his life view.

That trip was also a watershed point in Frank and my friendship. We remain friends to this day, but we were never again to be the really close friends that we were when we piled into Frank's car and headed west that February night to be with David. And the reason for this, too, can be found in Colin Wilson’s writings. Frank made the jump intuitively to Colin Wilson.

My embrace was more limited. I am Zweig. I am still climbing that ladder of Necessary Doubt.

.jpg)

.jpg)