In the delightful Albert Brooks movie Defending Your Life

(1991), the souls of the dead go to Judgment City, where they must

prove they deserve to break free from the reincarnation cycle and move

to a higher level of existence. During trials, prosecutors and defenders

support their arguments by showing film clips from the dead person's

life. (Yes, your most paranoid fantasies are true: Everything you've

ever done has been filmed and filed, and can eventually be used against

you.) The onward progress of Meryl Streep's character is assured by a

clip from the night her house caught fire. We see her rushing out of the

burning building, leading her two children to safety. Then we see her

rushing back in, flames all around her, to emerge moments later with the

family cat safe in her arms.

I don't know if Blake Snyder had this scene in mind when he wrote his 2005 guide to screenwriting,

Save the Cat! It seems possible. Snyder defines a Save the Cat scene as "the scene where we meet the hero and the hero

does something--like saving a cat--that defines who he is and makes us, the audience, like him."

True, he admits, not all protagonists are sterling sorts likely to save cats or help old ladies across the street. He cites

Pulp Fiction

as an example of a movie with protagonists who are, to put it mildly,

not very nice. (But even then, he argues, the writers manage to get us

interested in the protagonists, to come close to sympathizing with

them.)

I

think many insights in Snyder's book apply not only to movies but also

to novels and stories. As a writer, I've found his ideas about plot

structure helpful, and I've been careful to include Save the Cat scenes

in the first chapters of my recently released novel (

Interpretation of Murder) and my soon-to-be-released young adult novel (

Fighting Chance).

Much as I'd love to talk about my own books, though, I decided more

authoritative examples would provide more convincing support for

Snyder's ideas. So I pulled some mysteries and thrillers from my

bookshelf, not quite at random, and looked for Save the Cat scenes.

I'll start with an obvious example, Tom Clancy's

Patriot Games. Jack Ryan is strolling down a London street with his wife and daughter when he hears an explosion.

Grenade,

he realizes instantly. He hears a burst of gunfire, sees a Rolls Royce

forced to a halt in the middle of the street, sees one man firing a

rifle at it and another man racing toward its rear.

IRA, Ryan

thinks. He yanks his wife and daughter to the ground to keep them safe.

Then he takes off. He tackles one attacker, grabs his gun, shoots the

other attacker. Ryan gets shot, too, in the shoulder, but he hardly

notices. He's done what he had to do. He's protected his family and

stopped the attack. He's saved the cat.

So now we know, after only a few pages, that Jack

Ryan is observant, courageous, quick, and capable. His first thought is

to keep his wife and daughter safe, but he doesn't hesitate to risk his

own life to rescue the people in the Rolls. His actions match a pattern

we easily recognize as heroic. If we want to keep reading about him, if

we want to see him triumph, no wonder.

The second book I looked at was Dick Francis'

Banker. Even before I read

Save the Cat, I'd noticed how often Francis uses his first chapter to make us like and admire his protagonist.

Banker

begins when one of Tim Ekaterin's co-workers looks out a window at the

bank and sees an executive, Gordon Michaels, standing fully clothed in

the courtyard fountain. The co-worker exclaims about it but does nothing

more. Ekaterin "whisk[s] straight out of the deep-carpeted office,

through the fire doors, down the flights of gritty stone staircase and

across the marbled expanse of entrance hall." He rushes past a

"uniformed man at the security desk," who presumably should know how to

handle unsettling situations but instead stands "staring . . . with his

fillings showing," past two customers who are frozen in place, "looking

stunned." "I went past them at a rush into the open air," Ekaterin says,

"and slowed only in the last few strides before the fountain." He

tries to reason with his boss and learns Michaels is gripped by

hallucinations about "people with white faces," who are following him

and are, presumably, up to no good. The chairman of the bank, a "firm

and longtime" friend of Gordon Michaels, scurries into the courtyard.

"My dear chap," he says to his friend, but evidently can think of

nothing else to say, nothing else to do. He turns to Ekaterin."Do

something, Tim," he says.

"So I stepped into the fountain," Tim Ekaterin says.

He takes his boss by the arm, gently assures him he'll be safe even if

he leaves the fountain, gets him to come into the bank, takes him home,

helps get him into bed. Ekaterin's actions aren't heroic in a

traditional sense--he's never in physical danger--but he's shown himself

to be compassionate, intelligent, and determined. And he's

acted.

When other people are too stunned and stymied to do anything but stare,

Ekaterin runs past them "at a rush" and solves the problem. He saves

the cat.

Then there's Harry Kemelman's

Friday the Rabbi Slept Late,

the Edgar-winning first novel in the Rabbi Small series. David Small

doesn't have much in common with Jack Ryan. He's slight and pale, he'd

trip over his own feet if he tried to tackle a terrorist, and if he

picked up an a bad guy's gun, he wouldn't know how to fire it. But he

takes decisive actions when, in Chapter One, two of his congregants are

locked in a silly dispute about damages to a car one borrowed from the

other. The two men are longtime friends, but neither is willing to admit

he could be at fault, and both are so angry and frustrated they refuse

to talk to each other, or even to pray in the same room. Rabbi Small

persuades them to submit their case to an informal rabbinic court at

which he presides. As he explains his judgment, he applies centuries-old

Talmudic principles to this contemporary situation, displaying deep

knowledge of complicated texts, impressive mental agility, and

penetrating insight into human nature. By the time he's finished, the

two men are friends again, relieved to put their differences behind

them. The dispute about the car has no relevance to the novel's central

mystery, to the murder that hasn't yet been committed. But the scene has

served its purpose. We like and admire Rabbi Small and want to keep

reading about him. And, once again, the cat is safe.

A week or so ago, I bought Daphne Du Maurier's

Rebecca,

embarrassed to realize I'd never read it. It's a mystery classic, I'm a

mystery writer--high time I get down to business and read

Rebecca.

I started reading and felt the pull of that famous first sentence, of

that haunting opening description--the trees, the smokeless chimneys,

the threadlike drive, the nettles, the moonlight. Next comes the second

chapter's account of a couple living in a comfortless hotel, welcoming

boredom as an alternative to fear, waiting impatiently for newspapers

that bring them scores from cricket matches and schoolboy sports--not

because they care about such things, but because trivial news offers

some relief from the "ennui" that otherwise envelopes them. Then Chapter

Two merges into Chapter Three, into memories of a time when the

narrator was dominated by the repellant Mrs. Van Hopper and felt

incapable of fighting back. That's as far as I've gotten.

I'm not saying

Rebecca

isn't good. The quality of the writing impresses me, the situation

beginning to develop in Chapter Three intrigues me, and generations of

readers have loved this novel. There must be wonderful things lying

ahead. But I've got to admit I missed a Save the Cat scene. As I read

the opening chapters of

Rebecca, I kept waiting for the narrator to

do something.She didn't.

That, I think, is the essence of the Save the Cat scene. As Snyder says in his definition, "the hero

does something"--his italics. Or, as the befuddled chairman in

Banker says, "

Do something, Tim"--my italics.

I think readers are drawn to protagonists who

do

things. I'd guess that's probably true of most readers, especially true

of mystery readers. In mysteries, after all, there's always a problem

to be solved, an injustice to be set right. Sitting around and feeling

overwhelmed by circumstances doesn't cut it. Feeling sorry for oneself

definitely doesn't cut it. If we're going to commit ourselves to

spending time with a protagonist, we mystery readers want it to be

someone who responds to a tough situation by taking action. We can

forgive a protagonist who makes mistakes. Passivity, though--that's

harder to forgive.

I fully intend to read the rest of

Rebecca. But not yet. While I was browsing through my bookshelves to find examples for this post, I got hooked by a protagonist who

does things, who knows how to save a cat. I'll finish reading

Rebecca right after I finish re-reading

Friday the Rabbi Slept Late.

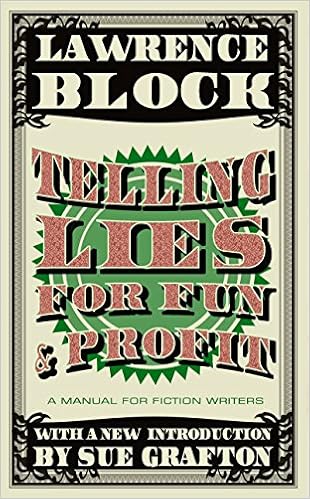

Have you ever stolen a idea for a story or book from another writer? No. Of course not, that's plagiarism, you say. You are exactly right. However, we all know in reality there are only thirty-six literary plots. Or maybe only twenty. Or perhaps only seven.

Have you ever stolen a idea for a story or book from another writer? No. Of course not, that's plagiarism, you say. You are exactly right. However, we all know in reality there are only thirty-six literary plots. Or maybe only twenty. Or perhaps only seven.

)