I attended high school so long ago that my class used Roman Numerals. My ninth-grade English teacher was the sister of Pulitzer-Prize-winning poet Theodore Roethke, and she was one of the best--and toughest--teachers I ever had. Because of her, I finished what was then called Junior High School with a better understanding of grammar than any healthy person should have to admit. I earned a "B" from her and was put into the honors English classes in high school because nobody else had earned a "B" from her since the Korean Conflict.

The honors classes all took a diagnostic grammar and usage test the first day, we all scored 177 of a possible 177, and the teacher called that our grammar for the year. We read lots of books, of course, and we did lots of writing, which was graded on our grammar, spelling, punctuation and general usage.

My senior class demanded a research paper of 1000 words, and we had to put footnotes at the bottom of the page and include a bibliography. The teacher promised us she would check our form carefully. I don't remember now whether we had six weeks to complete the assignment, or maybe even eight.

Six weeks, maybe eight, to complete a 1000-word essay. It works out to about 170 words a week, roughly 25 words a day. And we were graded on "correctness," with not a word about style or creativity. I don't remember anything changing in English classes until the 1980s.

In the mid 80s, I found several books that changed my teaching landscape. Peter Elbow's Writing Without Teachers brought the free-writing idea to daylight. Rico's Writing the Natural Way gave students stylistic models to emulate. Klauser's Writing on Both Sides of the Brain amplified both Elbow and Rico. Adams's The Care and Feeding of Ideas and Csikszentmihalyi's Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience set up the ground rules for how this stuff all worked.

Nobody else in my school seemed to notice these books, but they actually taught writing the way writers write: Say something, THEN worry about saying it more effectively or even "correctly."

Clarity and voice came first. For decades, we'd been trying to teach kids to say it right the first time, when we know that doesn't really happen.

Most of the English teachers I know are poor writers because they know grammar and punctuation so well that it gets in their way. When I retired from teaching, it took me about three years to accept that sometimes a sentence fragment works better than being correct.

One of the popular in-jokes was a facsimile lesson plan about teaching children how to walk. It buried the topic in medical jargon and psycho-babble and evaluation buzzwords until it became incoherent and impenetrable. The point was that if we taught kids basic life skills the way we taught them lessons in school, the human race would have died out long ago. (I'm carefully avoiding any mention of sex education here, maybe the only class that should be a performance-based subject...)

Back when I was in high school, golfers Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer both said that when they were learning the game, they were encouraged to hit the ball hard and concentrate on distance. They learned control and finesse later, and their records prove that it was the best way to learn.

That's how it should be with writing. Until you produce enough words to say something, don't worry about spelling or grammar.

Today, I expect to write 1000 words in an hour or so. My personal record for one day, back on an electric typewriter in 1981, is 42 pages, or about 10,000 words. I only had three weeks between the end of a summer grad school class and the beginning of my teaching year, so I just got stuff down on paper to fix later. The book was terrible and I later scrapped it, but that was ten times as many words as I'd done years before in eight weeks.

My second high, done to finish the first draft of a novel before I entered the hospital for surgery, was 7000 words.

If you're a writer, this probably doesn't shock you. I know many writers who set a 2000-word-a-day goal. If we'd asked that of kids in my generation, they would have all joined the Foreign Legion. That's because we were attacking the project from the wrong side. It's like pumping in the water before you dig the swimming pool.

Maybe this is why so many people say they don't write because they can't find a good idea. They may have perfectly good ideas, but they're afraid to begin because they fear doing it "wrong." It's the age old false equivalency over priorities: is it a candy mint or a breath mint?

If you think of your story, even in general terms with very little worked out yet, and start typing, the ideas will come. You may have to do lots of revision, but that's easy when you have material to work with. You can't fix what isn't there. The only document I get right the first time is a check because all I have to do is fill in the blanks. I take three drafts for the average grocery list.

Writing CAN be taught, but we have to teach the right stuff in the right order. It's no good obsessing abut correctness until you have something to "correct." We teach all the skills and have all the standards, but they're in the wrong sequence.

Don't raise the bar, bend it.

Teach kids the fun parts faster. I still remember teachers reading us stories in elementary school or the excitement of sharing our adventures in show-and-tell. Maybe if we kept the story first and worried about the finesse later, kids would grow into adults with more and better stories to share in the first place.

THEN you worry about style. There are dozens of books on grammar and usage--I've mentioned several of them before--but there are only two books I can mention about style, and Strunk and White is only really good for expository essays and academic subjects.

The other would be a required text in any class I taught. If you haven't read this, find a copy. I'm not going to discuss it because that could be another blog all by itself.

When I see kids reading on their screens or tablets instead of books, and watch them text with their thumbs, I have a few seconds of concern. But then I see how quickly they can type and the worry goes away. If they can produce communication that quickly, they can produce many short works quickly to make a longer one, and they can connect with each other. The phone abbreviations and emojis solve many of the concerns we obsessed over, too, like spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

Showing posts with label writing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label writing. Show all posts

05 August 2019

Bending The Bar

by Steve Liskow

Labels:

creativity,

grammar,

Steve Liskow,

style,

teaching,

word count,

writing

30 July 2019

Living in a Writing Rain Forest

by Barb Goffman

Recently Michael Bracken wrote here on SleuthSayers about living in a writing desert. He doesn't have a lot of authors who live near him in Texas. So he doesn't have author friends he can easily meet up with for lunch or a drink or a plotting session. In response to my comment that a friend once said that here in the Washington, DC, area, you couldn't swing a dead cat without hitting a mystery author, Michael said:

"I often wonder, Barb, how much being part of a thriving writing community or being in a writing desert impacts how our writing and our writing career develops. I sometimes think that if I moved somewhere where one can't swing a dead cat without hitting a mystery writer I might get too excited. I'd have too much fun being a writer and not enough time actually writing."

"I often wonder, Barb, how much being part of a thriving writing community or being in a writing desert impacts how our writing and our writing career develops. I sometimes think that if I moved somewhere where one can't swing a dead cat without hitting a mystery writer I might get too excited. I'd have too much fun being a writer and not enough time actually writing."

Well, I'm here today to say that I know with certainty that if I were living in a writing desert instead of the opposite (which I'm guessing is a writing rain forest--all that water, right?) I would not be writing these words on this blog, and I wouldn't be writing fiction at all.

|

| A real rain forest |

I remember when I first got the hankering to try to write crime fiction. It was in my first or second year of law school, and I had an idea for a book. I thought I would start writing it in my spare time (ha!), perhaps over the summer. But summer came and went, as did the rest of law school and my first year of practice as an attorney. And guess what? I didn't write that book. Not even one page.

One day I was thinking about the book. I wanted to write it, but three years (or so) had passed. Why hadn't I started writing? And I realized it was because I didn't know how to write a book. Legal briefs and memoranda, yes, those I knew how to write. Newspaper articles, yes, I could write those too. (I was a reporter before I went to law school.) But I wasn't trained in writing fiction. It was a mystery to me. (Ha again.) I knew there were rules I didn't know. I couldn't imagine how to start. Looking back, I realize I could have bought any number of how-to books, but I didn't. Instead, I decided that I didn't know how to write fiction, so I should just give up that dream.

But the dream wouldn't give up on me. Perhaps a week later, I saw an ad for an eight-week course starting in just a few weeks at a place called The Writers Center in Bethesda, Maryland. They were offering an introductory course on writing a mystery novel. The class would be on Saturday mornings, which fit into my schedule. The Writers Center was just a mile from my apartment. And I could afford the course. It was like fate was calling to me, "Don't give up!"

So I signed up for the course, and here I am, nearly two decades later, with 32 crime short stories published, four more accepted and awaiting publication, wins for the Agatha, Macavity, and Silver Falchion awards under my belt, as well as 27 nominations for national crime-writing awards. As for that first book, the one that prompted all of this ... I stopped writing it after chapter 12 or so. But I wrote another novel after it, and that one I finished. It sits in a drawer, awaiting one last polish. I may get to it someday ... or not because I've realized I love short stories, and when I get time to write, that's what I want to work on. So I do.

I never would have learned all of that and done all of that and accomplished all of that if I had been living in a writing desert. Without that first class at The Writers Center, I wouldn't have started writing fiction. I also wouldn't have been introduced to Sisters in Crime, specifically to members of the Chesapeake Chapter. I wouldn't have heard about mystery fan conventions Malice Domestic and Bouchercon. I wouldn't have started writing short stories. (I started down my short-story path because the Chessie Chapter had a call for stories for its anthology Chesapeake Crimes II.) Boiling it all down, if I were living in a writing desert, I wouldn't be me, not the me I've become. I'd probably still be working as an attorney instead of working full-time as a freelance crime fiction editor. (The pay is worse but the work suits me so much more.)

Living in this rain forest also has affected my life in other ways. My closest friends these days are all writers. When I lived in the Reston area, four other mystery authors lived within two miles of me. Other close friends lived less than a half hour away. We would go to lunches and dinners, talk about writing and plotting and life. Now that I live a little farther away, those meals happen a little less frequently, but they still happen. And thanks to Facebook, I'm never far from my writing tribe. It is the modern-day water cooler. I also talk to my pals on the phone regularly. (Yes, I'm a throwback!)

So I am utterly grateful I don't live in a writing desert. I can't imagine who I'd be if I did. And while I hope no one ever actually swings a dead cat my way, if that were the price I'd have to pay, I'd pay it. But who would swing a dead cat anyway? Mystery lovers are animal lovers, and we like our cats--and dogs--alive and slobbery. But that's a blog for another day.

***

And now for a little BSP: I'm delighted to share that a few days ago my story "Bug Appétit" was named a finalist for the Macavity Award for best mystery/crime short story of 2018. And I'm doubly happy to share this Macavity honor with my friend and fellow SleuthSayer Art Taylor, along with four other talented writers, Craig Faustus Buck, Leslie Budewitz, Barry Lancet, and Gigi Pandian. The winner will be announced on October 31st during Bouchercon. If you'd like to read "Bug Appétit" it's available on my website here. Or if you'd like to hear me read it to you, you can listen to it here. Once you reach the podcast page, click on my story title (Episode 114). Enjoy!

Labels:

Art Taylor,

Barb Goffman,

Macavity Awards,

Michael Bracken,

SinC,

Sisters-In-Crime,

writing

23 July 2019

The Future of Writing

Many of us have nostalgic, warm feelings of curling up with a book in the rain. For a lot of us here at SleuthSayers it’s more than likely a mystery or a thriller, though I’m sure we all read many different kinds of books, mainstream fiction, non-fiction, a little of everything.

But how many of our kids have that warm feeling? How many of our kids enjoy reading just for the pleasure of it? How many people read paper books anymore? And are young people reading these days? They do seem to read YA books, maybe on Kindle and iPad but not often in paperback. But they are reading less than previous generations and spending more time playing games on their phones, texting and watching movies instead of reading. More distractions and shorter attention spans. They’ve grown up with everything being faster and getting instant gratification. Do they ever read classics or history or something that’s a stretch for them? And how many never read anything longer than a Facebook post or Tweet?

My wife, Amy, who takes the train to work, says, “I notice on the train a lot of people staring at their phones. Some are reading, but the really serious readers have paperbacks or Kindles and don’t read on their phones. Most are texting or playing games. And it’s time that could be spent reading but they don’t. And that’s scary. I understand wanting to do something mindless and entertaining for a little while, but we also need to exercise and stretch our brains and imaginations sometimes, too.”

It seems to me that, while there are still some places to buy books besides Amazon, and that people still read, I’m not sure how many people read or what they’re reading. So the question is, is fiction a dying art? And how does that affect our writing?

Many people, of all ages, would find Don Quixote slow to come to a boil. Nothing happens for too long. That’s the way it is with a lot of books from earlier times and not even all that earlier. Hemingway was known for his “streamlining” of the language, but many people these days find his books slow going.

The same applies to movies. Even movies made 20 or 30 years ago are too slow for many people today. And when they watch movies they often watch them on a phone with a screen that’s five inches wide. How exciting is that? And many movies today are of the comic book variety. I’m not saying no one should read comic books or enjoy comic book movies, but it seems sometimes like that’s all there is in the theatres.

And novels have become Hollywoodized. I like fast paced things as much as the next person, but I also like the depth a novel can provide that movies or TV series often don’t. And one of the things that I liked about the idea of writing novels was being able to take things slower, to explore characters’ thoughts and emotions.

In talking to many people, I often find there’s a lack of shared cultural touchstones that I think were carried over from generation to generation previously. That also affects our writing. Should we use literary allusions, historical allusions? If so, how much do we explain them? And how much do we trust our audience to maybe look them up? The same goes for big words.

Way back when, I was writing copy for a national radio show. Another writer and I got called on the carpet one time and dressed down by the host. Why? Because we were using words that were “too big,” too many syllables. Words that people would have to look up. So, we dumbed down our writing to keep getting our paychecks. But it grated on us.

But in writing my own books and short stories I pretty much write them the way I want to. I’m not saying I don’t stop and consider using this word instead of that. But I hate writing down to people. When I was younger I’d sit with a dictionary and scratch pad next to me as I read a book. If I came on a word I didn’t know I’d look it up and write the definition down. And I learned a lot of new words that way. Today, if one is reading on a Kindle or similar device, it’s even easier. You click on the word and the definition pops up. That’s one of the things I like about e-readers, even though I still prefer paper books. But I wonder how many younger people look up words or other things they’re not familiar with.

And what if one wants to use a foreign phrase? I had another book (see picture) for looking those up. But again, today we’re often told not to use those phrases. Not to make people stretch. I remember seeing well-known writers (several over time) posting on Facebook, asking if their friends thought it was okay to use this or that word or phrase or historical or literary allusion because their editors told them they shouldn’t. That scares me.

So all of this brings up a lot of questions in my mind: What is the future of writing? Are we only going to write things that can be read in ten minute bursts? And then will that be too long? What does all this mean for writers writing traditional novels? Will everything become a short story and then flash fiction?

In 100 years will people still be reading and writing novels? Or will they live in a VR world where everything is a game and they can hardly tell reality from fantasy?

So, what do you think of all of this?

And now for the usual BSP:

My story Past is Prologue is out in the new July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Available now at bookstores and newstands as well as online at: https://www.alfredhitchcockmysterymagazine.com/. Hope you'll check it out.

Also, check out Broken Windows, the sequel to my Shamus Award-winning novel, White Heat.

But how many of our kids have that warm feeling? How many of our kids enjoy reading just for the pleasure of it? How many people read paper books anymore? And are young people reading these days? They do seem to read YA books, maybe on Kindle and iPad but not often in paperback. But they are reading less than previous generations and spending more time playing games on their phones, texting and watching movies instead of reading. More distractions and shorter attention spans. They’ve grown up with everything being faster and getting instant gratification. Do they ever read classics or history or something that’s a stretch for them? And how many never read anything longer than a Facebook post or Tweet?

My wife, Amy, who takes the train to work, says, “I notice on the train a lot of people staring at their phones. Some are reading, but the really serious readers have paperbacks or Kindles and don’t read on their phones. Most are texting or playing games. And it’s time that could be spent reading but they don’t. And that’s scary. I understand wanting to do something mindless and entertaining for a little while, but we also need to exercise and stretch our brains and imaginations sometimes, too.”

It seems to me that, while there are still some places to buy books besides Amazon, and that people still read, I’m not sure how many people read or what they’re reading. So the question is, is fiction a dying art? And how does that affect our writing?

Many people, of all ages, would find Don Quixote slow to come to a boil. Nothing happens for too long. That’s the way it is with a lot of books from earlier times and not even all that earlier. Hemingway was known for his “streamlining” of the language, but many people these days find his books slow going.

The same applies to movies. Even movies made 20 or 30 years ago are too slow for many people today. And when they watch movies they often watch them on a phone with a screen that’s five inches wide. How exciting is that? And many movies today are of the comic book variety. I’m not saying no one should read comic books or enjoy comic book movies, but it seems sometimes like that’s all there is in the theatres.

And novels have become Hollywoodized. I like fast paced things as much as the next person, but I also like the depth a novel can provide that movies or TV series often don’t. And one of the things that I liked about the idea of writing novels was being able to take things slower, to explore characters’ thoughts and emotions.

In talking to many people, I often find there’s a lack of shared cultural touchstones that I think were carried over from generation to generation previously. That also affects our writing. Should we use literary allusions, historical allusions? If so, how much do we explain them? And how much do we trust our audience to maybe look them up? The same goes for big words.

Way back when, I was writing copy for a national radio show. Another writer and I got called on the carpet one time and dressed down by the host. Why? Because we were using words that were “too big,” too many syllables. Words that people would have to look up. So, we dumbed down our writing to keep getting our paychecks. But it grated on us.

But in writing my own books and short stories I pretty much write them the way I want to. I’m not saying I don’t stop and consider using this word instead of that. But I hate writing down to people. When I was younger I’d sit with a dictionary and scratch pad next to me as I read a book. If I came on a word I didn’t know I’d look it up and write the definition down. And I learned a lot of new words that way. Today, if one is reading on a Kindle or similar device, it’s even easier. You click on the word and the definition pops up. That’s one of the things I like about e-readers, even though I still prefer paper books. But I wonder how many younger people look up words or other things they’re not familiar with.

And what if one wants to use a foreign phrase? I had another book (see picture) for looking those up. But again, today we’re often told not to use those phrases. Not to make people stretch. I remember seeing well-known writers (several over time) posting on Facebook, asking if their friends thought it was okay to use this or that word or phrase or historical or literary allusion because their editors told them they shouldn’t. That scares me.

So all of this brings up a lot of questions in my mind: What is the future of writing? Are we only going to write things that can be read in ten minute bursts? And then will that be too long? What does all this mean for writers writing traditional novels? Will everything become a short story and then flash fiction?

In 100 years will people still be reading and writing novels? Or will they live in a VR world where everything is a game and they can hardly tell reality from fantasy?

So, what do you think of all of this?

~.~.~

And now for the usual BSP:

My story Past is Prologue is out in the new July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Available now at bookstores and newstands as well as online at: https://www.alfredhitchcockmysterymagazine.com/. Hope you'll check it out.

Also, check out Broken Windows, the sequel to my Shamus Award-winning novel, White Heat.

Please join me on Facebook: www.facebook.com/paul.d.marks and check out my website www.PaulDMarks.com

Click here to: Subscribe to my Newsletter

Labels:

Alfred Hitchcock,

mystery magazine,

novels,

Paul D. Marks,

reading,

tips,

writing

17 July 2019

Because It Isn't There

by Robert Lopresti

I'm going to give in to peer pressure and follow Steve Liskow, Michael Bracken, R.T. Lawton, and O'Neil De Noux in addressing the question: Why write?

* When I was in second grade I brought a pencil and notebook to school determined that I would write a new Winnie-the-Pooh story. I remember my shock in realizing that I had no idea how to do that. Why did I want to write? Because there were only two Pooh books and that clearly wasn't enough.

* In sixth grade our English teacher encouraged us to write short stories. I wrote a few spy stories (in slavish devotion to The Man From Uncle) and Mrs. Sonin, bless her heart, would let me read them to her after school while she graded papers. I hope to heaven she didn't listen because they were uniformly awful. Why did I write? Because I loved to read and wanted to add more stories to the world.

* While living in a dorm at graduate school I found time to write a novel, which I had the good sense not to submit anywhere. I still have the handwritten draft but, as Robert Benchley said about his diary, no one will see it as long as I have a bullet in my rifle. Why did I write? Because I wanted to be a writer and I needed something to do other than study cataloging.

* At the same time I started submitting terrible short stories to magazines. Why? Because I thought I might have a career as a writer.

* After three years of trying I sold a story to Mike Shayne's Mystery Magazine. The rush I got from seeing my name in print gave me a reason to write for many years.

And other stuff happened, but that's enough.

Let's sum things up, shall we. Why do I write?

As Thomas Berger said: "Because it isn't there."

I'm going to give in to peer pressure and follow Steve Liskow, Michael Bracken, R.T. Lawton, and O'Neil De Noux in addressing the question: Why write?

* When I was in second grade I brought a pencil and notebook to school determined that I would write a new Winnie-the-Pooh story. I remember my shock in realizing that I had no idea how to do that. Why did I want to write? Because there were only two Pooh books and that clearly wasn't enough.

* In sixth grade our English teacher encouraged us to write short stories. I wrote a few spy stories (in slavish devotion to The Man From Uncle) and Mrs. Sonin, bless her heart, would let me read them to her after school while she graded papers. I hope to heaven she didn't listen because they were uniformly awful. Why did I write? Because I loved to read and wanted to add more stories to the world.

* While living in a dorm at graduate school I found time to write a novel, which I had the good sense not to submit anywhere. I still have the handwritten draft but, as Robert Benchley said about his diary, no one will see it as long as I have a bullet in my rifle. Why did I write? Because I wanted to be a writer and I needed something to do other than study cataloging.

* At the same time I started submitting terrible short stories to magazines. Why? Because I thought I might have a career as a writer.

* After three years of trying I sold a story to Mike Shayne's Mystery Magazine. The rush I got from seeing my name in print gave me a reason to write for many years.

And other stuff happened, but that's enough.

Let's sum things up, shall we. Why do I write?

As Thomas Berger said: "Because it isn't there."

08 July 2019

Why I Write

by Steve Liskow

Today, I'm following a trend started by Michael Bracken, R.T., and O'Neil.

Writing is something I've done for so long that I can't imagine not doing it. Restructuring my life without it would be like a dancer having to reinvent himself after losing both legs.

The previous generation of my family included several teachers and two journalists, then called "reporters." My sister and I are the two youngest of eleven first cousins, seven of whom taught at one time or another (One was a principal and another was a superintendent), three of whom were involved in theater, and two of whom became attorneys.

Adults read to us constantly from the time we could sit upright in their laps. My sister and I both read at a fourth-or-fifth-grade level when we entered kindergarten, and I assume our cousins did, too.

When I was ten, the Mickey Mouse Club presented their first serialization of The Hardy Boys, and over the next year, I read every existing book in the series. Naturally, I tried to copy them myself, both sides of a wide-ruled notebook page per chapter, ending with the hero getting hit over the head or a flaming car soaring over the cliff. My mother, who worked as a secretary for the Red Cross during World War II, typed a couple of my stories out, and seeing my word in print gave me a thrill that never went away.

I slowed down in high school and college, but I never really stopped writing. In grad school, I took an American short story class that brought back the urge. Between 1972 and 1981, I taught high school English, earned my Masters and C.A.S (sixth-year) from Wesleyan, worked part-time as a photographer...and wrote five unpublished novels. Then I drifted into theater, where I acted, directed, produced, designed lights and/or sound and helped build sets for over 100 productions between 1982 and 2010. My third grad degree is in theater.

I retired from teaching in 2003, and the theater where I did most of my work lost its performance space a week later. I wanted to revise one of the books I'd never been able to sell, and now I had time to learn to do it right. I read books on craft, attended workshops, and asked questions. Three years and 350 rejections later, I sold my first short story. Four more years and 250 more rejections, and I sold my first novel. Since then five short stories (including that first one) have short-listed for the Al Blanchard Award. I've won Honorable Mention three times, but never won. Two other stories won the Black Orchid Novella Award (Rob Lopresti has also won), and one story, the ONLY story that was accepted the first place I sent it, was nominated for an Edgar.

As I write this, most of the other bloggers on this site sell more short stories in a slow year than I have even written in my life. My acceptance rate hovers around seven percent and I have eight stories still floating from market to market looking for a home. My fifteen novel (All self-published since the first one became a terrible experience) will appear late this year or early next year.

Since 2007, when my first story appeared in print, my writing enterprises have been in the black three times, and the largest amount was about a hundred dollars. If I stopped writing today, it wouldn't affect my income or my standard of living.

My quality of life, though, well, that's a different issue.

I was a shy kid. Even though I could play baseball and football and basketball fairly well and had a bike like the other kids, I always felt a little bit outside the group. The writing gave me a retreat that was safe. So did music. I studied violin in firth grade (I really wanted to play piano) and picked up a guitar when the Beatles invaded. I played bass in a fortunately forgotten band in college. I recently started teaching myself piano all these years later, and music appears in many of my stories. Theater shows up occasionally.

I don't write for the money or for the recognition. I write because I still like the furniture in my little interior retreat. I love how it feels to send out a story when I know it's the best I can make it. That doesn't mean it will sell. A story I think is one of my very best has 19 rejections and no other appropriate market on the horizon. Another one I love has 15.

So what?

Would I like to make more money writing? Sure. I'd also like to play piano and guitar better, be twenty years younger knowing what I know now, and lose 15 pounds.

But I'll settle for this.

Writing is something I've done for so long that I can't imagine not doing it. Restructuring my life without it would be like a dancer having to reinvent himself after losing both legs.

The previous generation of my family included several teachers and two journalists, then called "reporters." My sister and I are the two youngest of eleven first cousins, seven of whom taught at one time or another (One was a principal and another was a superintendent), three of whom were involved in theater, and two of whom became attorneys.

Adults read to us constantly from the time we could sit upright in their laps. My sister and I both read at a fourth-or-fifth-grade level when we entered kindergarten, and I assume our cousins did, too.

When I was ten, the Mickey Mouse Club presented their first serialization of The Hardy Boys, and over the next year, I read every existing book in the series. Naturally, I tried to copy them myself, both sides of a wide-ruled notebook page per chapter, ending with the hero getting hit over the head or a flaming car soaring over the cliff. My mother, who worked as a secretary for the Red Cross during World War II, typed a couple of my stories out, and seeing my word in print gave me a thrill that never went away.

I slowed down in high school and college, but I never really stopped writing. In grad school, I took an American short story class that brought back the urge. Between 1972 and 1981, I taught high school English, earned my Masters and C.A.S (sixth-year) from Wesleyan, worked part-time as a photographer...and wrote five unpublished novels. Then I drifted into theater, where I acted, directed, produced, designed lights and/or sound and helped build sets for over 100 productions between 1982 and 2010. My third grad degree is in theater.

|

| Upper Right, me as the crazy father |

I retired from teaching in 2003, and the theater where I did most of my work lost its performance space a week later. I wanted to revise one of the books I'd never been able to sell, and now I had time to learn to do it right. I read books on craft, attended workshops, and asked questions. Three years and 350 rejections later, I sold my first short story. Four more years and 250 more rejections, and I sold my first novel. Since then five short stories (including that first one) have short-listed for the Al Blanchard Award. I've won Honorable Mention three times, but never won. Two other stories won the Black Orchid Novella Award (Rob Lopresti has also won), and one story, the ONLY story that was accepted the first place I sent it, was nominated for an Edgar.

|

| Linda Landrigan on the left, Jane Cleland on the right. Second Black Orchid |

As I write this, most of the other bloggers on this site sell more short stories in a slow year than I have even written in my life. My acceptance rate hovers around seven percent and I have eight stories still floating from market to market looking for a home. My fifteen novel (All self-published since the first one became a terrible experience) will appear late this year or early next year.

Since 2007, when my first story appeared in print, my writing enterprises have been in the black three times, and the largest amount was about a hundred dollars. If I stopped writing today, it wouldn't affect my income or my standard of living.

My quality of life, though, well, that's a different issue.

I was a shy kid. Even though I could play baseball and football and basketball fairly well and had a bike like the other kids, I always felt a little bit outside the group. The writing gave me a retreat that was safe. So did music. I studied violin in firth grade (I really wanted to play piano) and picked up a guitar when the Beatles invaded. I played bass in a fortunately forgotten band in college. I recently started teaching myself piano all these years later, and music appears in many of my stories. Theater shows up occasionally.

|

| One of my last directing gigs |

|

| The book I finally got right. |

So what?

Would I like to make more money writing? Sure. I'd also like to play piano and guitar better, be twenty years younger knowing what I know now, and lose 15 pounds.

But I'll settle for this.

Labels:

awards,

black orchid,

Edgar Awards,

novellas,

short stories,

Steve Liskow,

writing

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

02 July 2019

Tess Gerritsen: What Makes Books Fail?

In my last post for SleuthSayers I briefly mentioned Tess Gerritsen and her keynote speech at the California Crime Writers Conference. Leigh asked if I could talk a little more about what she said, so here goes:

I really enjoyed her speech, it was funny and relatively short—about twenty minutes. And it kept my interest. Much of what I say here is quoted or paraphrased closely from her speech. But I think I misstated her premise in my last piece, saying she talked about What Not to Do. More accurately her speech was about What Makes Books Fail. She started with some anecdotes and wound her way around to that topic.

She opened talking about how happy she was to be in sunny SoCal. Though it hasn’t been as sunny here as it normally is. But I guess coming from Maine anything above 50 is sunny.

She segued into Delia Owens and her phenomenal success with Where the Crawdads Sing. She also talked about The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, by Mary Ann Shaffer and her niece Annie Barrows which spent many weeks on the NY Times best seller list. Delia Owens was 70 when her debut novel came out. Shaffer, author of Potato Peel was 74 …and died before it came out. The point was it doesn’t matter how old you are or what you look like. You just have to do it. And you don’t even have to be alive to be a debut novelist!

She moved on to talk about something we can all relate to. One day, while in her local grocery store, the butcher smiled at her over the meat counter. Then came running out after her—hopefully not with a butcher knife raised over his head.

“I knew you’d be in here eventually,” he said. “I want to give you this.”

Three guesses as to what he wanted to give her. Okay, time’s up.

He brandished a manuscript—what else? She took it. And to cut to the chase it never got published, at least not traditionally.

Another time she was in a restaurant. A man across from her jumped out of his chair, dashing out of the restaurant. He returned 20 minutes later with a briefcase…holding, well, you know what it was holding.

And then she talked about love, at least Shakespeare in Love. But rather than try to retell what she said, this, from her website, pretty much covers it:

“Young Shakespeare writes ‘Romeo and Juliet’, falls in love, and tries to stay one step ahead of the Queen’s guard. The scene that had me laughing hardest? When a ferryman finds out that Shakespeare’s a writer and asks him, ‘Will you read my manuscript?’”

Do you notice a theme here?

But the real theme of her talk was why some novels get published and others don’t. Why didn’t the butcher’s novel get published? The real theme was:

What Makes Books Fail

Ms. Gerritsen said that there are certain mistakes that are made often that keep one from breaking out or getting a traditional contract. By way of illustration, she talked about Uncle Harry. We all have one, right?

Uncle Harry and Aunt Maude both experienced the same earth shattering event. Harry will talk your ear off, telling you everything that happened, blow by blow, and bore you to death. Maude will tell you the same story and keep you on the edge of your seat. What’s the difference? Maude gives you the high points of the story.

Tess says we need to identify where the emotional high points are. It’s not that Harry isn’t intelligent, but he needs to get a sense of the dramatic. That’s why Maude’s version is better.

She told the story of Michael Palmer’s agent taking him on, even though the agent didn’t like the book, because they thought he had a sense of the dramatic. And when she and Palmer, both doctors, taught a course in writing for other docs who wanted to be novelists, they discovered that most of them, intelligent as they are, and as understanding of all the tech aspects, couldn’t tell a good story because they didn’t have that sense of the dramatic.

And her heart dropped when an attorney-friend of hers wrote a book and wanted to talk to her about it. But, she thought, he does interesting stuff so maybe it would be okay, and agreed to meet for lunch. And this is what she said:

“His book was about a man who comes of age in the turbulent 60s and moves to Maine. ‘And what happens,’ I asked. ‘It’s about self-discovery, about the journey, about coming to grips with life,’ he said. ‘But what happens,’ I said, ‘where’s the conflict? Where’s the struggle?’ And he said, ‘life is a/the struggle.’ And I thought okay, we’re in trouble. So the more I pressed him on the plot and the characters, the more I heard about actualization and personal journeys and maximizing relationships. And in a fit of frustration, I finally just said, ‘you’re thinking too hard. You should be feeling the story,’ and that’s what I’ve come to conclude, is that what makes most stories fail is that people are thinking too hard and they’re not feeling their way. In a nutshell, writers really shouldn’t be cerebral, shouldn’t be logical. We should be thinking about the dramatic points in our lives, the emotional centers in our lives.”

And one more example: Another man wrote a scene about a family preparing a BBQ. He wrote it in great detail, the cooking, the salads, every little thing. And then his grown child telling the dad that “we’re going to have a baby.” That’s great, the dying dad says, congratulations, and they go in and have dinner. But the author didn’t let the characters chew on that. Didn’t play off the emotional core of the scene, the dying man becoming a grandfather. It was just glossed over.

Tess said she remembers the day she was told she was going to have her first grandchild. Her son, who has a flair for the dramatic, showed her a sonogram on the rim of the Grand Canyon. She and her husband started sobbing. She doesn’t remember the hike or how she got to the rim. She only remembers about the baby, now her five year old granddaughter. So, she told the man writing about the BBQ he shouldn’t pass over the emotional center so quickly and spend so much time on the steaks being medium rare. She couldn’t remember the trip to the Grand Canyon. Every bit about the salad or how the steaks were cooked wasn’t what was important.

How a book fails, she said, is that we fail to remember that we’re human beings. It’s all about emotions, not about telling. And a large part of our skill is choosing the scenes—which scene/s are you going to point out? What are the details that matter to you? And even though we sometimes have to deal with technical aspects of what’s happening, we still need to find the emotional things there.

She used her book Gravity as an example. She had to explain the technical aspects of a spacewalk. But she didn’t have the heart of her story until she read Into Thin Air, where one of the climbers, who knew he was doomed to die on the mountain, called his wife to say goodbye. That brought Tess to tears and gave her the spark for the emotional center for Gravity. What is your last goodbye going to be like? Make your story interesting by bringing in your emotions.

So, even when you do need to tell, as we sometimes do, you need to find the emotions of the scene. Show something from the point of view of what you and your characters are feeling.

The bottom line:

What she’s learned is: trust your heart. That’s where your story needs to be. Don’t tell, but show. Choose the scenes that have the highest amount of gravitas and angst, and maybe we’ll all be Delia Owens someday.

And now for the usual BSP:

My story Past is Prologue is out in the new July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Available now at bookstores and newstands as well as online at: https://www.alfredhitchcockmysterymagazine.com/. Also in this issue are fellow SleuthSayers Janice Law, R.T. Lawton and B.K. Stevens. Hope you'll check it out.

I really enjoyed her speech, it was funny and relatively short—about twenty minutes. And it kept my interest. Much of what I say here is quoted or paraphrased closely from her speech. But I think I misstated her premise in my last piece, saying she talked about What Not to Do. More accurately her speech was about What Makes Books Fail. She started with some anecdotes and wound her way around to that topic.

She opened talking about how happy she was to be in sunny SoCal. Though it hasn’t been as sunny here as it normally is. But I guess coming from Maine anything above 50 is sunny.

She segued into Delia Owens and her phenomenal success with Where the Crawdads Sing. She also talked about The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, by Mary Ann Shaffer and her niece Annie Barrows which spent many weeks on the NY Times best seller list. Delia Owens was 70 when her debut novel came out. Shaffer, author of Potato Peel was 74 …and died before it came out. The point was it doesn’t matter how old you are or what you look like. You just have to do it. And you don’t even have to be alive to be a debut novelist!

|

| Delia Owens |

|

| Mary Ann Shaffer and her niece Annie Barrows |

“I knew you’d be in here eventually,” he said. “I want to give you this.”

Three guesses as to what he wanted to give her. Okay, time’s up.

He brandished a manuscript—what else? She took it. And to cut to the chase it never got published, at least not traditionally.

Another time she was in a restaurant. A man across from her jumped out of his chair, dashing out of the restaurant. He returned 20 minutes later with a briefcase…holding, well, you know what it was holding.

And then she talked about love, at least Shakespeare in Love. But rather than try to retell what she said, this, from her website, pretty much covers it:

“Young Shakespeare writes ‘Romeo and Juliet’, falls in love, and tries to stay one step ahead of the Queen’s guard. The scene that had me laughing hardest? When a ferryman finds out that Shakespeare’s a writer and asks him, ‘Will you read my manuscript?’”

Do you notice a theme here?

But the real theme of her talk was why some novels get published and others don’t. Why didn’t the butcher’s novel get published? The real theme was:

What Makes Books Fail

Ms. Gerritsen said that there are certain mistakes that are made often that keep one from breaking out or getting a traditional contract. By way of illustration, she talked about Uncle Harry. We all have one, right?

Uncle Harry and Aunt Maude both experienced the same earth shattering event. Harry will talk your ear off, telling you everything that happened, blow by blow, and bore you to death. Maude will tell you the same story and keep you on the edge of your seat. What’s the difference? Maude gives you the high points of the story.

Tess says we need to identify where the emotional high points are. It’s not that Harry isn’t intelligent, but he needs to get a sense of the dramatic. That’s why Maude’s version is better.

She told the story of Michael Palmer’s agent taking him on, even though the agent didn’t like the book, because they thought he had a sense of the dramatic. And when she and Palmer, both doctors, taught a course in writing for other docs who wanted to be novelists, they discovered that most of them, intelligent as they are, and as understanding of all the tech aspects, couldn’t tell a good story because they didn’t have that sense of the dramatic.

|

| Tess Gerritsen at the 2019 California Crime Writers Conference |

“His book was about a man who comes of age in the turbulent 60s and moves to Maine. ‘And what happens,’ I asked. ‘It’s about self-discovery, about the journey, about coming to grips with life,’ he said. ‘But what happens,’ I said, ‘where’s the conflict? Where’s the struggle?’ And he said, ‘life is a/the struggle.’ And I thought okay, we’re in trouble. So the more I pressed him on the plot and the characters, the more I heard about actualization and personal journeys and maximizing relationships. And in a fit of frustration, I finally just said, ‘you’re thinking too hard. You should be feeling the story,’ and that’s what I’ve come to conclude, is that what makes most stories fail is that people are thinking too hard and they’re not feeling their way. In a nutshell, writers really shouldn’t be cerebral, shouldn’t be logical. We should be thinking about the dramatic points in our lives, the emotional centers in our lives.”

And one more example: Another man wrote a scene about a family preparing a BBQ. He wrote it in great detail, the cooking, the salads, every little thing. And then his grown child telling the dad that “we’re going to have a baby.” That’s great, the dying dad says, congratulations, and they go in and have dinner. But the author didn’t let the characters chew on that. Didn’t play off the emotional core of the scene, the dying man becoming a grandfather. It was just glossed over.

Tess said she remembers the day she was told she was going to have her first grandchild. Her son, who has a flair for the dramatic, showed her a sonogram on the rim of the Grand Canyon. She and her husband started sobbing. She doesn’t remember the hike or how she got to the rim. She only remembers about the baby, now her five year old granddaughter. So, she told the man writing about the BBQ he shouldn’t pass over the emotional center so quickly and spend so much time on the steaks being medium rare. She couldn’t remember the trip to the Grand Canyon. Every bit about the salad or how the steaks were cooked wasn’t what was important.

How a book fails, she said, is that we fail to remember that we’re human beings. It’s all about emotions, not about telling. And a large part of our skill is choosing the scenes—which scene/s are you going to point out? What are the details that matter to you? And even though we sometimes have to deal with technical aspects of what’s happening, we still need to find the emotional things there.

She used her book Gravity as an example. She had to explain the technical aspects of a spacewalk. But she didn’t have the heart of her story until she read Into Thin Air, where one of the climbers, who knew he was doomed to die on the mountain, called his wife to say goodbye. That brought Tess to tears and gave her the spark for the emotional center for Gravity. What is your last goodbye going to be like? Make your story interesting by bringing in your emotions.

So, even when you do need to tell, as we sometimes do, you need to find the emotions of the scene. Show something from the point of view of what you and your characters are feeling.

The bottom line:

What she’s learned is: trust your heart. That’s where your story needs to be. Don’t tell, but show. Choose the scenes that have the highest amount of gravitas and angst, and maybe we’ll all be Delia Owens someday.

~.~.~

And now for the usual BSP:

My story Past is Prologue is out in the new July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Available now at bookstores and newstands as well as online at: https://www.alfredhitchcockmysterymagazine.com/. Also in this issue are fellow SleuthSayers Janice Law, R.T. Lawton and B.K. Stevens. Hope you'll check it out.

Please join me on Facebook: www.facebook.com/paul.d.marks and check out my website www.PaulDMarks.com

Click here to: Subscribe to my Newsletter

Labels:

Alfred Hitchcock,

California,

mystery magazine,

Paul D. Marks,

Tess Gerritsen,

tips,

writers,

writing

25 June 2019

If I Should Die Before I Wake

The recent passing of Sandra Seamans, whose blog “My Little Corner” was a must-visit for every mystery short story writer seeking publication, reminds me once again of how important it is to ensure that our families are aware of our writing lives. They often know little about our on-line and off-line publishing activities, the organizations of which we are members, the editors and publishers with whom we engage, and the many friends—some of whom we have never met outside of social media, blog posts, and email—we have in the writing community.

Obituaries are often written in haste by family members who are grieving, and the literary endeavors of the departed are often of little concern to those mourning the death of a spouse, parent, or child. If mentioned at all, these endeavors are likely glossed over.

Certainly, immediate family members, close friends, and employers get notified. Families of those who were members of churches, synagogues, and mosques likely notify the deceased’s religious leaders and their worship community. But who ensures that the writing community learns of the writer’s passing?

Some of us are lucky. We have spouses who are active participants in our writing lives. They attend conventions with us, invite fellow writers into our homes, have met some of our editors, know to which group blogs we contribute, and know of which professional organizations we are members. Not all of us are so lucky.

Especially for those whose family members are not active participants in our writing lives, but also as an aid to those who are, we should prepare a few important documents. The obvious are a medical power of attorney, a will with a named executor familiar with our literary endeavors (some writers more knowledgeable than I recommend a literary executor in addition to the regular executor), and funeral instructions.

May I also suggest a draft of one’s obituary? I just updated mine, ensuring that my writing life is documented appropriately.

Family members will likely remember to notify employers—for those of us with day jobs—but will they know to notify professional organizations such as the Mystery Writers of America and Private Eye Writers of America? May I suggest a list of organizations in which one is a member, including contact information.

Those left behind will likely not understand our record-keeping systems, so an explanation of how to determine what projects are due and will remain undelivered, what submissions are outstanding, what stories have been accepted for publication but have not yet been published, and what might still be required of accepted stories (copyedits, reviews of page proofs, writing of author bios, and so on).

And then there’s the money. We don’t just receive checks in the mail. We also have regular royalty payments deposited directly into our bank accounts, and we receive both one-time and regular royalty payments via PayPal. Can those left behind access our accounts after our demise, and do they understand the financial loss if they close accounts without ensuring that all regular royalty payments and one-time payments are rerouted to the estate’s accounts?

I’m certain there is much more our families need to know about our writing lives, so forgive me if I’ve failed to mention something important. But just looking at what I’ve already outlined lets me know that I have much to do to prepare my family—and I’m one of the lucky writers whose spouse plays an active role in my writing life.

Guns + Tacos launches next month, and y’all don’t want to miss even a single episode of this killer new serial novella anthology series, created by me and Trey R. Barker and published by Down & Out Books. First up: Gary Phillips with Tacos de Cazuela con Smith & Wesson. Then in August comes my novella Three Brisket Tacos and a Sig Sauer, followed each month thereafter by novellas by Frank Zafiro, Trey R. Barker, William Dylan Powell, and James A. Hearn.

|

| Sandra Seamans |

Certainly, immediate family members, close friends, and employers get notified. Families of those who were members of churches, synagogues, and mosques likely notify the deceased’s religious leaders and their worship community. But who ensures that the writing community learns of the writer’s passing?

Some of us are lucky. We have spouses who are active participants in our writing lives. They attend conventions with us, invite fellow writers into our homes, have met some of our editors, know to which group blogs we contribute, and know of which professional organizations we are members. Not all of us are so lucky.

Especially for those whose family members are not active participants in our writing lives, but also as an aid to those who are, we should prepare a few important documents. The obvious are a medical power of attorney, a will with a named executor familiar with our literary endeavors (some writers more knowledgeable than I recommend a literary executor in addition to the regular executor), and funeral instructions.

May I also suggest a draft of one’s obituary? I just updated mine, ensuring that my writing life is documented appropriately.

Family members will likely remember to notify employers—for those of us with day jobs—but will they know to notify professional organizations such as the Mystery Writers of America and Private Eye Writers of America? May I suggest a list of organizations in which one is a member, including contact information.

Those left behind will likely not understand our record-keeping systems, so an explanation of how to determine what projects are due and will remain undelivered, what submissions are outstanding, what stories have been accepted for publication but have not yet been published, and what might still be required of accepted stories (copyedits, reviews of page proofs, writing of author bios, and so on).

And then there’s the money. We don’t just receive checks in the mail. We also have regular royalty payments deposited directly into our bank accounts, and we receive both one-time and regular royalty payments via PayPal. Can those left behind access our accounts after our demise, and do they understand the financial loss if they close accounts without ensuring that all regular royalty payments and one-time payments are rerouted to the estate’s accounts?

I’m certain there is much more our families need to know about our writing lives, so forgive me if I’ve failed to mention something important. But just looking at what I’ve already outlined lets me know that I have much to do to prepare my family—and I’m one of the lucky writers whose spouse plays an active role in my writing life.

Guns + Tacos launches next month, and y’all don’t want to miss even a single episode of this killer new serial novella anthology series, created by me and Trey R. Barker and published by Down & Out Books. First up: Gary Phillips with Tacos de Cazuela con Smith & Wesson. Then in August comes my novella Three Brisket Tacos and a Sig Sauer, followed each month thereafter by novellas by Frank Zafiro, Trey R. Barker, William Dylan Powell, and James A. Hearn.

Labels:

Frank Zafiro,

Gary Phillips,

Michael Bracken,

Sandra Seamans,

William Dylan Powell,

writers,

writing

23 June 2019

When Showing Tells

by Leigh Lundin

Addicted to the Hard Stuff

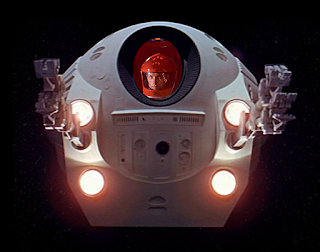

From about age eight, I devoured science fiction with a passion. If I’d read Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The Sentinel’ then, I didn’t recall. Certainly I wouldn’t have guessed it would inspire arguably the finest science fiction film of the past half century. I didn’t make the connection at the time.

Nothing was going to stop this impecunious Greenwich Village student from seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey. For one thing, few critics and even fewer directors understand ‘hard science’ fiction. Those meager numbers unsurprisingly thin as a shrinking percentage of the populace take science itself seriously.

Back in April 1968, articles and advance marketing drove the buzz in New York City. Writers droned on and on about the beauty of the space ballet. Computer trade journals discussed the technology of HAL. Gossip columnists debated how to pronounced the lead actor’s name. New York’s theatre scene gushed that the chimps were portrayed by dancers. Much later we’d learn they were acted out by professional mimes.

Within days, the excited film talk turned to disillusion and disappointment. Even SF fans emerged from the premier saying, “Huh?”

WTF?

Foremost, the original cut fell victim to that movie-goer tendency to rush from a theatre before the first credit rolls. (The credits stampede has become such an annoying phenomenon that some directors reward fans who sit through until the end with further scenes.) Back then, fatigued by 2001’s seemingly endless ‘acid trip’, theatres emptied moments before the crux of the story revealed itself. Audiences missed the entire point of the story.

Stanley Kubrick sliced and diced the ‘acid trip’ (now called ‘star gate’) and reworked the production’s final few minutes. Even so, readers had to wait for Clarke to finish the novel written in parallel to piece together the entire affair. Clarke’s earlier 1948/1951 short story wouldn’t prove helpful at all.

Down the Wrong Path

As a penniless student, I refused to miss a second of the film’s original two hours, forty minutes. Although I remained through the ending, I left confused for a different reason. Not until the book came out did I realize a common story-telling technique misled me:

To demonstrate I wasn’t the only person led astray, I quote Wikipedia:

That happened, but that’s not what happened. To flesh in more detail:

That key led some to a false conclusion:

The monolith triggered violence and aggression.

The writers had intended the scene to show:

The monolith precipitated evolution.

No one knows how many viewers interpreted the scene wrongly. Between that problem and the abortive rush-out-the-door ending, Kubrick and Clarke managed to confuse an entire city and probably an entire nation.

Afterword

I hazard the filmmakers became blinded by proximity– they’d grown too close to that vignette to realize it could lead to misunderstanding. A fix could have been easy.

Afterward

Nonetheless, I love 2001. Revisions have clarified and far more answers are available now than on opening day.

Months later, I would see another of my favorites in that same theatre district, Silent Running. About the same time while still on a student budget, a faded poster lured me to spend a couple of hours in a drab Greenwich Village dollar theatre, an elephant graveyard of soon-to-be-forgotten films. Filmed on a shoestring budget, that obscure celluloid strip turned out a gem in the rough. THX-1138 was the product of an unknown 24-year-old writer/director… George Lucas.

Arthur C Clarke’s short story? After seventy years, it shows its age, but it’s worth reading. We’re pleased to bring you ‘The Sentinel’ PDF and MP3/M4B audiobooks. You can also read or listen to 2001: A Space Odyssey provided for free by the thoughtful people at BookFrom.net. To listen or download, don't be misled by the nearby ‘Text-to-Speech’ icon, but click on the Listen 🔊 link in the upper right corner of the page.

From about age eight, I devoured science fiction with a passion. If I’d read Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The Sentinel’ then, I didn’t recall. Certainly I wouldn’t have guessed it would inspire arguably the finest science fiction film of the past half century. I didn’t make the connection at the time.

Nothing was going to stop this impecunious Greenwich Village student from seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey. For one thing, few critics and even fewer directors understand ‘hard science’ fiction. Those meager numbers unsurprisingly thin as a shrinking percentage of the populace take science itself seriously.

Back in April 1968, articles and advance marketing drove the buzz in New York City. Writers droned on and on about the beauty of the space ballet. Computer trade journals discussed the technology of HAL. Gossip columnists debated how to pronounced the lead actor’s name. New York’s theatre scene gushed that the chimps were portrayed by dancers. Much later we’d learn they were acted out by professional mimes.

Within days, the excited film talk turned to disillusion and disappointment. Even SF fans emerged from the premier saying, “Huh?”

WTF?

Foremost, the original cut fell victim to that movie-goer tendency to rush from a theatre before the first credit rolls. (The credits stampede has become such an annoying phenomenon that some directors reward fans who sit through until the end with further scenes.) Back then, fatigued by 2001’s seemingly endless ‘acid trip’, theatres emptied moments before the crux of the story revealed itself. Audiences missed the entire point of the story.

Stanley Kubrick sliced and diced the ‘acid trip’ (now called ‘star gate’) and reworked the production’s final few minutes. Even so, readers had to wait for Clarke to finish the novel written in parallel to piece together the entire affair. Clarke’s earlier 1948/1951 short story wouldn’t prove helpful at all.

Down the Wrong Path

As a penniless student, I refused to miss a second of the film’s original two hours, forty minutes. Although I remained through the ending, I left confused for a different reason. Not until the book came out did I realize a common story-telling technique misled me:

Showing, Not Telling

To demonstrate I wasn’t the only person led astray, I quote Wikipedia:

| “ | In an African desert millions of years ago, a tribe of hominids is driven away from its water hole by a rival tribe. They awaken to find a featureless black monolith has appeared before them. Seemingly influenced by the monolith, they discover how to use a bone as a weapon and drive their rivals away from the water hole. | ” |

|---|

That happened, but that’s not what happened. To flesh in more detail:

| Following the unveiling of the monolith, these ancestral apes take up long bones as clubs. In a slow-motion orgy of destruction, they bash discarded skulls into shards. In the next scene, they enthusiastically wield clubs to kill their hated enemies. |

That key led some to a false conclusion:

The monolith triggered violence and aggression.

The writers had intended the scene to show:

The monolith precipitated evolution.

No one knows how many viewers interpreted the scene wrongly. Between that problem and the abortive rush-out-the-door ending, Kubrick and Clarke managed to confuse an entire city and probably an entire nation.

Afterword

I hazard the filmmakers became blinded by proximity– they’d grown too close to that vignette to realize it could lead to misunderstanding. A fix could have been easy.

- The primates drive away sabre-tooth tigers or woolly mammoths, not a warring primate clan.

- The primates learn to dig, devise, or divert water using their evolving brains, not brawn.

Afterward

Nonetheless, I love 2001. Revisions have clarified and far more answers are available now than on opening day.

Months later, I would see another of my favorites in that same theatre district, Silent Running. About the same time while still on a student budget, a faded poster lured me to spend a couple of hours in a drab Greenwich Village dollar theatre, an elephant graveyard of soon-to-be-forgotten films. Filmed on a shoestring budget, that obscure celluloid strip turned out a gem in the rough. THX-1138 was the product of an unknown 24-year-old writer/director… George Lucas.

Arthur C Clarke’s short story? After seventy years, it shows its age, but it’s worth reading. We’re pleased to bring you ‘The Sentinel’ PDF and MP3/M4B audiobooks. You can also read or listen to 2001: A Space Odyssey provided for free by the thoughtful people at BookFrom.net. To listen or download, don't be misled by the nearby ‘Text-to-Speech’ icon, but click on the Listen 🔊 link in the upper right corner of the page.

Labels:

2001,

Arthur C. Clarke,

Leigh Lundin,

lessons,

writing

22 June 2019

Ten Minutes of Comedy at the Arthur Ellis Awards Gala (and they even let me stay on stage...)

The Crime Writers

of Canada went loco, and asked me to emcee the Arthur Ellis Awards this

year. Somehow they learned I might have

done standup in the past. Or maybe not,

because they even paid me. It may be

more than my royalties this quarter.

I dug back into

my Sleuthsayer files to decide what might appeal to a hardened (read soused)

group of crime writers en mass, with an open bar. This is what resulted, and I’m happy to say

the applause was generous. You may

remember some of this.

Arts and Letters

Club, Toronto, May 23, 2019, 9PM

Hello! Mike said I could do a few minutes of comedy

this evening as long as I apologized in advance.

My name is

Melodie Campbell, and it’s my pleasure to welcome here tonight crime writers,

friends and family of crime writers, sponsors, agents, and any publishers still

left out there.

Tonight is that

special night when the crime writing community in Canada meets to do that one

thing we look forward to all year: which

is get together and bitch about the industry.

Many of you knew

my late husband Dave. He was a great

supporter of my writing, and of our crime community in general. But many times, he could be seen wandering

through the house, shaking his head and muttering “Never Marry a crime writer.”

I’ve decided,

here tonight, to list the reasons why.

Everybody knows

they shouldn’t marry a crime writer.

Mothers the world over have made that obvious: “For Gawd Sake, never

marry a marauding barbarian, a sex pervert, or a crime writer.” (Or a

politician, but that is my own personal bias.

Ignore me.)

But for some

reason, lots of innocent, unsuspecting people marry authors every year. Obviously, they don’t know about the

“Zone.” (More obviously, they didn’t

have the right mothers.)

Never mind: I’m

here to help.

I think it pays

to understand that crime writers aren’t normal humans: they write about people

who don’t exist and things that never happened.

Their brains work differently.

They have different needs. And in

some cases, they live on different planets (at least, my characters do, which

is kind of the same thing.)

Thing is, authors

are sensitive creatures. This can be

attractive to some humans who think that they can ‘help’ poor writer-beings (in

the way that one might rescue a stray dog.)

True, we are easy to feed and grateful for attention. We respond well to praise. And we can be adorable. So there are many reasons you might wish to

marry a crime writer, but here are 10 reasons why you shouldn’t:

The basics:

1 Crime Writers are hoarders. Your house will be filled with books. And more books. It will be a shrine to books. The lost library of Alexandria will pale in

comparison.

2 Crime Writers are addicts. We mainline coffee. We’ve also been known to drink other

beverages in copious quantities, especially when together with other writers in

places called ‘bars.’

3 Authors are weird. Crime Writers are particularly weird (as

weird as horror writers.) You will hear all sorts of gruesome research details

at the dinner table. When your parents

are there. Maybe even with your parents

in mind.

4 Crime Writers are deaf. We can’t hear you when we are in our offices,

pounding away at keyboards. Even if you come in the room. Even if you yell in our ears.

5 Crime Writers are single-minded. We think that spending perfectly good

vacation money to go to conferences like Bouchercon is a really good idea. Especially if there are other writers there

with whom to drink beverages.

And here are some worse reasons why you

shouldn’t marry a crime writer:

6 It may occasionally seem that we’d rather

spend time with our characters than our family or friends.

7 We rarely sleep through the night. (It’s hard to sleep when you’re typing. Also, all that coffee...)

8 Our Google Search history is a thing of

nightmares. (Don’t look. No really – don’t. And I’m not just talking about ways to avoid

taxes… although if anyone knows a really fool-proof scheme, please email me.)

And the really

bad reasons:

9 If we could have affairs with our beloved

protagonists, we probably would. (No!

Did I say that out loud?)

10 And lastly, We know at least twenty ways to

kill you and not get caught.

RE that last

one: If you are married to a crime

writer, don’t worry over-much. Usually

crime writers do not kill the hand that feeds them. Most likely, we are way too focused on

figuring out ways to kill our agents, editors, and particularly, reviewers.

Finally, it seems appropriate to finish with the first joke I ever sold, way back in the 1990s:

Recent studies show that approximately 40% of writers are manic depressive. The rest of us just drink.

Melodie Campbell can be found with a bottle of Southern Comfort in the True North. You can follow her inane humour at www.melodiecampbell.com

Labels:

Arthur Ellis,

awards,

Canada,

comedy,

crime,

crime writers,

humor,

humour,

publishers,

writers,

writing

18 June 2019

Professional Tips from Screenwriters

Introducing John Temple…

|

| John Temple |

John Temple is a veteran investigative journalist whose books shed light on significant issues in American life.

Forthcoming next Tuesday, June 25th, John’s newest book, Up in Arms: How the Bundy Family Hijacked Public Lands, Outfoxed the Federal Government, and Ignited America’s Patriot Movement, chronicles Cliven and Ammon Bundys’s standoffs with the federal government.

His last book, American Pain: How a Young Felon and His Ring of Doctors Unleashed America’s Deadliest Drug Epidemic, was named a New York Post “Favorite Book of 2015” and was a 2016 Edgar Award nominee. American Pain documented how two young felons built the largest pill mill in the United States and also traced the roots of the opioid epidemic. John has spoken widely about the opioid epidemic to audiences that include addiction counselors, medical professionals, lawyers, and law enforcement.

John also wrote The Last Lawyer: The Fight to Save Death Row Inmates (2009) and Deadhouse: Life in a Coroner’s Office (2005). The Last Lawyer won the Scribes Book Award from the American Society of Legal Writers. More information about John’s books can be found at www.JohnTempleBooks.com.

John Temple is a tenured full professor at West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media, where he teaches journalism. He studied creative nonfiction writing at the University of Pittsburgh, where he earned an M.F.A. John worked in the newspaper business for six years. He was the health/education reporter for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, a general assignment reporter for the News & Record in Greensboro, N.C., and a government and politics reporter for the Tampa Tribune in Tampa, FL. I've had the pleasure of knowing him for more than twenty years, since attending law school with his wife. I'm so pleased to let you all meet and learn from such a great journalist and storyteller.

— Barb Goffman

Learning from Screenwriters

by John Temple

In 2006, I read a book that changed the trajectory of my writing life. I was beginning work on my second nonfiction book, about a North Carolina lawyer who defended death row inmates, when a screenwriter friend recommended I read Syd Field’s 1979 book, Screenplay, which is a sort of holy text for Hollywood screenwriters.

I wasn’t a screenwriter, but I soon realized why the book had such an impact. Somehow, even after many years of working as a newspaper reporter, devouring numerous writing books, and earning an MFA in creative nonfiction, I had never come across such solid, practical advice about how stories are built. Among other ideas, Field advocated a fairly strict three-act structure as the screenplay ideal, but for me the single most helpful concept in his book involved “beats.”

Most screenwriters agree that their chief mission is to find the story’s moments of change, which they call beats. In a screenplay, where efficiency is key, those transformative moments determine whether a scene or sequence earns its pages. In every scene, something must occur that alters either the character’s mindset or the stakes or the dramatic action. In my last three books, all nonfiction crime stories, I’ve tried to consciously seek out the moments of change that my various characters have experienced, and let those beats dictate how I structured the books. I’m looking for the events that contain catalytic moments that alter the protagonist or the surroundings and further the story. Those are the moments I seek to present as full-fledged scenes, rich with vivid detail. The rest is summary.

Sometimes, a beat can be dramatic and external. As Raymond Chandler wrote: “When in doubt, have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand.” (What Chandler actually meant by that quote is somewhat more complicated.) However, the most intriguing and pivotal beats often involve internal change, which is often a decision or realization. In my 2015 book, American Pain, which chronicled the rise and fall of the nation’s largest painkiller pill mill, the owner realized how much money he stood to make if he could avoid the Drug Enforcement Administration’s scrutiny. That meant he needed to clamp down on his doctors and staff. This was a key moment of change for this primary character. So instead of breezing through that section of the book in an expository way, I meticulously looked for moments and details that would illuminate that beat. There were many other moments of obvious drama in the book – train crashes, overdoses, a kidnapping, drug busts – but that change in the character’s outlook felt more important to the overall story.