Last Saturday, I attended a writing conference for the first time in much too long. The in-person attendance was sparse, but many people chose to attend on Zoom. I considered that, but I knew a few writers attending and wanted to catch up. Besides, Tess Gerritsen was the Guest of Honor and Alison Gaylin was on a panel and I wanted to meet them both, especially since Gaylin's The Collective may be the best book I've read so far this year.

|

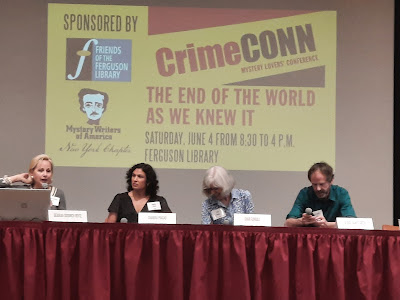

| The "Changes" panel getting ready |

Crime Conn is now a regular event (barring the pandemic) at the Ferguson Library in Stamford, CT, about 35 miles west of New Haven. That makes it an hour's drive for me, and I got there in time for coffee and donuts and greeting a few friends before the presentations began. The program offered five 45-minute panels with time in between to buy books and get them signed. You can never have too many books and never meet too many crime writers, who are among the most generous people on earth.

The theme of this year's conference was The End of the World As We Knew It, complete with the REM track introducing the festivities. For the music buffs, the panels were "Cha-cha-cha-cha-changes," examining what's different for writers now; "The Eve of Destruction," discussing whether or not this is the Apocalypse; "Forever Young," presenting three YA authors explaining how they help young readers navigate the New Crazy; "Psycho Killer," three current or former law enforcement officers and a death investigator from the CT State Medical Examiner; and "I'll Be There For You," looking at how the last two years of isolation, hostility, and shifting rules have helped writers create or maintain relationships. The final presentation, "Doctor My Eyes," featured John Valeri, a Connecticut book critic and one of mystery writingt's best friends, interviewing Tess Gerritsen.

|

| MWA Chapter Pres Al Tucher welcomes the guests |

I'm pretty sure Chris Knopf, one of the organizers, came up with the titles. That night, he would be playing bass in a band. He and I shared tales of how arthritis affects our guitar playing, but he's still probably much better than I am.

Rather than discuss each panel in depth, here are a few pithy comments from the writers.

From the Changes panel: Multi-racial and gender identity are important in this changing world. Roughly 10% of today's kids are multi-racial, but only 1% of the books out there have a multi-racial character. We have to represent "Different" accurately.

The Eve of Destruction panel asked "Will pandemic books sell?" The idea reappeared in other panels, but the prevailing wisdom is that 9/11 books still don't (the only exception I know might be SJ Rozan's Absent Friends), and we're still too close to Covid. When asked about upping the ante in today's world, the authors stressed that the best approach is not to amp up the crime, but to become more human. I was one of many who appreciated that emphasis on character over "stuff."

The YA writers (I bought books by two of them because they impressed me on the panel) pointed out that backstory informs character NOW. What in the past will make them afraid in the present?

The law enforcement officers explained, among other things, how Covid has changed policing. The New Haven detective observed that the streets were much quieter at first, and that she became leery of interacting with the public. All three panelists tried to minimize arrests and bringing people into enclosed cells. They agreed they'd seen an increase in domestic violence. One officer-turned-writer has not yet included Covid in his work and commented, "It's easier to read and write about adversity after it's over."

|

| Audience at left. The tables of books for sale in the background |

Wendy Corso Staub and Alison Gaylin shared many writers' problems with trying to write when they were no longer alone all day because their hsuband was working from home and the children were learning online instead of in a school. Staub reverted to early morning writing as she did years ago. She would feed her infant child, then stay up and write for several hours before going back to bed. Over the last two years of lockdown, she has completed four novels.

Tess Gerritsen wanted to write from the time she was seven, but her parents encouraged her to study other fields. She majored in anthropology as an undergrad, became a physician, and plays several musical instruments between writing now. She said, "It doesn't matter what you study, it matters what you LIVE."

The gathering was small enough so writers and audience mingled easily. There was a writing workshop during the lunch break for those who were interested, too.

I sat at a table with Lynn, now working on her first nonfiction book, and Chris, who has not written anything… yet. They both attended the writing workshop. As the conference wound down, they weren't the only ones who looked eager to get back home so they could resume writing.

That's what a good conference does.