By Art Taylor

A few years back, one of the professors

in the English Department at George Mason University (where I myself

teach) told me that she never put her own favorite books on the syllabi

for any of her classes; seeing what the students said about them was too

heart-breaking for her.

I'm

currently teaching a class called "Five Killer Crime Novels"—a gen ed

survey of some of milestone books in the genre, or at least books that

serve to represent/illustrate some of the trends and range and depth of

mystery and suspense fiction. So far, we've read Arthur Conan Doyle's Hound of the Baskervilles, Agatha Christie's Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest, along with a sprinkling of short stories; still ahead are Ed McBain's Sadie When She Died and Megan Abbott's Bury Me Deep. (And yes, I know there are tons and tons of others that could've/should've made the list!)

Whether I'd count these books as all-time favorites or not (Red Harvest certainly is), each

of these are books I love, one way or another. And indeed it is a

little heart-breaking to have students talk (spoiler alerts!) about how

disappointed they are by various aspects of the three we've read so far.

"We finally see the hound and then in the next paragraph they just

shoot him and that's it?" And: "She could've cut about 50 pages toward the end of Roger Ackroyd. It was so slow and so boring." And then: "I'm sorry, Professor Taylor, but Red Harvest just sucks."

I'll

admit it; my internal response to that last one was along the lines of

"You think your comment shows your superiority, but really it just

reveals your ignorance." But I would never say that publicly, of course.

(Oh, wait.... Whoops.)

Actually,

I try not to take offense to these kinds of comments and criticisms,

but instead try to transform them into productive aspects of class

discussion. The complaint about Hound of the Baskervilles, for

example—that quick movement from the hound's appearance in one paragraph

to his demise in the next—leads to a closer look at serialization and

how the publication schedule built suspense. The eighth installment of the story in The Strand

ends strategically at the break between those two paragraphs, with

these words: "Never in the delirious dream of a disordered brain could

anything more savage, more appalling, more hellish be conceived than

that dark form and savage face which broke upon us out of the wall of

fog."

AND STAY TUNED FOR WHAT HAPPENS NEXT!

A different effect, right?

Other

reactions call for deeper discussion: Why are certain scenes included?

What is the potential purpose of such-and-such artistic decisions? What

are the potential effects on the reader? Why structure and pace a scene

this way? or a chapter? or a succession of chapters? Or more to the

point: Can you articulate why you think this book "sucks"? The key isn't

the judgement itself—pro or con—but backing up judgements with evidence

and authority.

"Red Harvest was just a

bloodbath. I couldn't both to get connected to the characters, because

after a while, I knew they were just going to die. And nobody seemed to

care, not even the detective—and we're not connected to him either. We

don't even get his name!"

OK, let's dig deeper into all that, I'll say—and then we do.

My

point here isn't to criticize my students or to celebrate my own

tactics in the classroom. My students are—fortunately!—a bright and

active bunch, and our discussions are often sharp and insightful. But I

do wonder sometimes about the reasons behind some of those gut responses

of boredom, dismissal, dislike.

Is it that students have been so conditioned by today's various media—the pacing of a CSI episode,

for example, or the short bursts of information that constitute news,

or the structures and expectations of Facebook status updates, tweets,

and IM exchanges—that older works become dated in more

fundamental ways than just their vocabulary or dress or gender

attitudes? Maybe today's modes of communication and storytelling are so

different that the average student can't relate.

Is

the issue about the age or era of a book at all, or is it something

about the genre itself (crime fiction) or the form (a novel) that is the

impediment? Sisters in Crime has done studies about the demographics of

mystery readers (an aging one, as it turns out),

and many students in my gen ed classes these days don't count

themselves as readers at all—not in a conventional sense, even as their

days often consist of more reading in other ways than most "grown-ups"

do.

Is it that many of my students in this class—a

gen ed class, drawing mostly on majors outside the humanities—simply

aren't interested in literature at all, so the process itself might be

with some level of disinterest or even hostility?

I

don't know the answer to these questions. Likely some deeper study would

be required, and maybe I haven't even asked the right questions or

framed any of this properly in the first place. Either way, I'd love to

hear what others think.

In the meantime, however, an anecdote to end this on a more positive note—a story I've told before:

A

few years ago, we'd come to the end of the semester for a class that

examined hard-boiled detective fiction as social documentary (maybe my

favorite class of all the lit courses I've taught). It was final exam

day, and students were turning in their exams as they completed them,

mumbling quick good-byes, and heading out of the classroom, done for the

semester.

One student turned in her exam and then

walked around the desk to where I was sitting, gave me a big smile, and

held out her arms wide.

I have to admit, I find myself

disinclined to hug students—for a variety of reasons, as you might

imagine—so I didn't stand but just sat there, gave her a "what's this?

look or gesture of some kind, I can't really remember.

But

I do remember what she said: "Professor Taylor, before this semester,

I'd never read an entire novel, and now I've read six of them."

I stood.

I hugged.

We're

Facebook friends now, and she has a daughter of her own these days, and

my hope isn't simply that she's continuing to read herself but that

she's reading to that daughter too.

Showing posts with label Agatha Christie. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Agatha Christie. Show all posts

30 October 2015

19 October 2015

Good Books and Old Movies, Part II

by Susan Rogers Cooper

I mentioned last post that I was teaching classes

on the mystery from novel to film, and listed the books and

movies I'd be teaching. Rob Lopresti had done a little research

on my first author, John Buchan, creator of "The Thirty-Nine

Steps," and sent me his blog on him, which was quite

interesting.

Buchan was a Scot, which might have had something to do with his grand descriptions of the Scottish countryside in "The 39 Steps," and began his adult life with a brief legal career, which he gave up for his real passion -- writing. On October 19, 1915, John Buchan's first novel, "The Thirty-nine Steps" was published and was an immediate hit, selling 25,000 copies by the end of the year. It tells the story of Richard Hannay, a South African visiting London who gets caught up in an espionage ring. Jason Worden argued that Buchan actually invented a new sub-genre: the story in which a civilian gets chased both by the bad guys, and by the police who think he is the bad guy. That paranoia made it perfect for Alfred Hitchcock, who not only filmed "The Thirty-nine Steps," but used a similar plot in two other movies. Buchan wrote many more novels, including four about the plucky Richard Hannay. During World War I, his penchant for writing came in handy as he wrote propaganda for the British government. He also served as Governor General of Canada until his death in 1940. As Rob said, not bad for a thriller writer.

Buchan was a Scot, which might have had something to do with his grand descriptions of the Scottish countryside in "The 39 Steps," and began his adult life with a brief legal career, which he gave up for his real passion -- writing. On October 19, 1915, John Buchan's first novel, "The Thirty-nine Steps" was published and was an immediate hit, selling 25,000 copies by the end of the year. It tells the story of Richard Hannay, a South African visiting London who gets caught up in an espionage ring. Jason Worden argued that Buchan actually invented a new sub-genre: the story in which a civilian gets chased both by the bad guys, and by the police who think he is the bad guy. That paranoia made it perfect for Alfred Hitchcock, who not only filmed "The Thirty-nine Steps," but used a similar plot in two other movies. Buchan wrote many more novels, including four about the plucky Richard Hannay. During World War I, his penchant for writing came in handy as he wrote propaganda for the British government. He also served as Governor General of Canada until his death in 1940. As Rob said, not bad for a thriller writer.

Learning all this about John Buchan made me want

to learn more about the other writers I was featuring in my class.

Although John Buchan was the least known (to me anyway) of the four,

I decided to delve a little deeper into the others. I knew

before hand -- from general knowledge and reading Lillian Hellman's

wonderful book "Pentimento" -- that Dashiel Hammett had

worked as a detective for the Pinkerton agency, was an alcoholic, and

had issues with rejection -- at least according to Ms. Hellman.

Delving a little deeper, I learned that Samuel Dashiel Hammett worked

for the Pinkertons from 1915 to 1922, quitting due to the Pinkertons

penchant for strike breaking. Almost all of his books and short

stories were written in the 1920s and '30s, due in part to his bad

health and his interest in political activism. He joined The Civil

Rights Congress (the CRC), a leftist organization, and soon became

their president. The CRC came under scrutiny in the late 1940s, and

Hammett was subpoenaed to appear before a judge to name a list of

contributors to a defense fund set up by the CRC for people accused

of communist sympathies. He refused, citing the fifth amendment, and

was sent to federal prison. Only a few years later, in the early

1950s, he was blacklisted by the HUAC and was unable to work as a

writer from that point until his death in 1961. Raymond Chandler

wrote in The Simple Art of Murder, “Hammett was the ace

performer... He is said to have lacked heart; yet the story he

himself thought the most of, The Glass Key, is the record of a

man's devotion to a friend. He was spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he

did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at

all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

And speaking of Raymond Chandler, one of my all

time favorite writers, I was interested to learn that he didn't start

writing until 1932 at the age of forty-four. A former oil company

executive, he lost his job during the Great Depression and decided to

take up writing. In a letter to his London publisher, Hamish

Hamiton, Chandler explained why he began reading and eventually

writing for pulp magazines: “Wandering up and down the Pacific

Coast in an automobile I began to read pulp magazines, because they

were cheap enough to throw away and because I never had at any time

any taste for the kind of thing which is known as women's magazines.

This was in the great days of the Black Mask (if I may call

them great days) and it struck me that some of the writing was pretty

forceful and honest, even though it had its crude aspect. I decided

that this might be a good way to try to learn to write fiction and

get paid a small amount of money at the same time. I spent five

months over an 18,000 word novelette and sold it for $180. After that

I never looked back, although I had a good many uneasy periods

looking forward.”

In the introduction to Trouble Is My Business

(1950), a collection of four of his short stories, Chandler wrote,

“The emotional basis of the standard detective story was and had

always been that murder will out and justice will be done. Its

technical basis was the relative insignificance of everything except

the final denouement. What led up to that was more or less passage

work. The denouement would justify everything. The technical basis of

the Black Mask type of story on the other hand was that the

scene outranked the plot, in the sense that a good plot was one which

made good scenes. The ideal mystery was one you would read if the end

was missing. We who tried to write it had the same point of view as

the film makers. When I first went to Hollywood a very intelligent

producer told me that you couldn't make a successful motion picture

from a mystery story, because the whole point was a disclosure that

took a few seconds of screen time while the audience was reaching for

its hat. He was wrong, but only because he was thinking of the wrong

kind of mystery.”

Chandler also described the struggle that the

writers of pulp fiction had in following the formula demanded by the

editors of the pulp magazines: “As I look back on my stories it

would be absurd if I did not wish they had been better. But if they

had been much better they would not have been published. If the

formula had been a little less rigid, more of the writing of that

time might have survived. Some of us tried pretty hard to break out

of the formula, but we usually got caught and sent back. To exceed

the limits of a formula without destroying it is the dream of every

magazine writer who is not a hopeless hack.” And in a radio

discussion with Chandler, Ian Fleming said that Chandler offered

"some of the finest dialogue written in any prose today".

After Chandler's wife died, he began drinking

heavily and slid into a severe depression. He attempted suicide but

called the police before the attempt to tell them he was going to do

it. He died in 1959.

My final author of course needs no introduction to

anyone – mystery buff or not. Agatha Christie is almost as well

known as Santa Claus. She published sixty-six novels and fourteen

short story collections. She was initially unsuccessful in getting

published, but in 1920 “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” was

published, introducing the world to Hercule Poirot. The Guinness

Book of World Records lists Dame Agatha as the best selling author of

all time.

Much has been made of her ten day disappearance

after her husband asked for a divorce. A much maligned movie,

“Agatha,” was made – with a large disclaimer at the beginning –

with a fanciful explanation as to what occurred. It has never been

made public what happened in that ten day period.

In 1930 Dame Agatha married archeologist Sir Max

Mallowan, whom she met during an archaeological dig. Their marriage

lasted until Christie's death in 1976.

Location:

Austin, TX, USA

05 October 2015

Good Books and Old Movies, Part I

by Susan Rogers Cooper

I've been honored over the past few years to be asked to teach classes at

Austin's Lifetime Learning Institute. This is a wonderful

organization for people 55+ to take classes in just about anything

and for a very nominal fee. I've taught classes on writing the

mystery a couple of times, which is always fun – especially when

I'm able to dazzle my students with guest speakers like Jan Grape and

Joan Hess.

This semester I'm teaching a class called: “The Mystery: From Novel to

Film.” We read the book, we watch the movie. And we compare and

contrast. Our first book was John Buchan's “The Thirty-Nine

Steps,” and, of course, we watched the Hitchcock movie version.

There were a lot of differences, the main being that in the book

there were no women – in the movie there were plenty. I preferred

the movie myself. As did a lot of the class.

Our second movie was the William Powell and Myrna Loy version of Dashiel

Hammett's “The Thin Man.” After rereading the book, I noted that

the alcohol consumption was even higher in the book than in the

movie, and those people could drink!

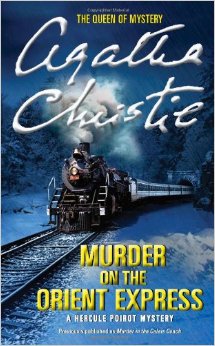

Tomorrow we watch the 1974 version of Dame Agatha's “Murder on the Orient

Express,” with Albert Finney as Hercule. I'm rereading the book

now and have come full circle in my appreciation of Christie's

talent. She was amazing. Even knowing the ending, I'm still

fascinated with how she got there.

It's going to take two classes to watch all of that very long movie, but

the next, and last, movie will star two of my favorite actors in the

film version of a book by one of my favorite writers: the Bogart and

Bacall version of Raymond Chandler's “The Big Sleep.”

Teaching this class has given me a chance to reread some classic mysteries and

re-watch some wonderful old movies. I'm already thinking about next

semester and what new treasures I can share.

Any suggestions?

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

Dashiell Hammett,

John Buchan,

movies,

Raymond Chandler

Location:

Austin, TX, USA

07 September 2015

What Makes A Mystery?

What makes a mystery? The three main

characters help: The victim, the protagonist, and the villain.

The victim can be a nice person who

didn’t deserve to get murdered, or a vicious schemer that had folks

lining up to get a crack at him. What’s important from a plot

standpoint is that the victim has lived their life so that they die

NOW, at this particular place and time, and while in contact with a

particular group of people.

The protagonist, or detective – be

they a cop, private investigator, or amateur –

must

have a strong interest in solving this crime. A police officer would

have a strong professional interest. A PI would have both a personal

and a professional interest in solving the crime – the professional

because they’ve been hired; and personal because – as the story

progresses – they begin to care about avenging the victim or feel a

strong personal responsibility to the client. An amateur would

probably always be personal – to avenge someone they cared for, or

to clear their own name or the name of a loved one. If

the protagonist is given a strong motivation to solve the case, this

helps move the plot forward because it keeps the protagonist moving

forward.

And

the whole reason for the story: the murderer. There are all sorts

of killers, but in fiction we writers like to stick with the tried

and true: a serial killer, a murder for gain (money or love), or

someone who thinks they have no other choice. This is my personal

favorite and I find it most interesting. The person who commits the

crime has been driven to this point by circumstances so horrendous

that they thought murder was the only solution to their problem.

What

would motivate a person to be murdered? Or to murder? What are the

forces that drive a person? Is it money, love, security, or, most

likely, a combination of them all? How would this person react if

they were involved in a mystery? Would they be an active

participant, in either detection or deceit, or would they attempt to

extricate themselves from the situation? Is this a violet person or

a passive person? What

are this person’s interests and what do they tell us about the

character? What is their physical appearance and what does that tell

us about the character?

Agatha

Christie may have thought of the peculiarities of a twisty plot, but

to make it work she had to people it w/ characters that could live in

that plot. Example: MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS. I’ve no doubt

she thought of the clever twist as to who committed the murder before

she thought of the characters on that train, but once she decided on

that plot, she had to fill the Orient Express with characters who

were capable of living out that plot and making it as believable as

possible. Dame Agatha was a brilliant plotter, but she

concentrated more on twists designed to shock a reader than she did

on twists that emerged from the interactions of characters. Today’s

plots are centered more on the interactions of characters rather than

dependent on a cleaver means of killing a victim.

In

my own books, character has a lot to do w/ the plot. Milt Kovak is a

small town sheriff in Oklahoma, in a town he’s lived in all his

life. He knows just about everybody in town. In most cases he knows

the victim, and eventually, the murderer. The plot usually centers

on the murder itself – as in a police procedural – but with lots

of detours involving Milt’s many side characters – his staff at

the sheriff’s department, his wife and son, his sister, and

whatever else seems to be happening in Prophesy County, Oklahoma.

My

E.J. Pugh series is more traditional, or cozy if you will. E.J. is

an amateur sleuth whose first experience (ONE, TWO, WHAT DID DADDY

DO?) is gruesomely personal. Actually, all the books have a personal

interest for E.J., and many of them stem from something in my own

family's life – not that we've experienced any murders, but, hey,

what if?

In

a traditional mystery there is usually a strong link in life between

the killer and the victim. This immediately advances some of the

plot: What were the circumstances that led to the killer’s

decision to take a life? Was it an easy decision, a spur of the

moment decision, or an idea that went terribly wrong?

In

a mystery, the plot is the story. But it must ring true. Sometimes

it's hard for an amateur sleuth to continually stumble over dead

bodies and make that ring true, but there are other things in that

story that should – the amateur's reasons for investigating, their

knowledge of the victim, and their feelings about it. The truth is

what matters in any story, and there should always be a nugget that

our readers can take away.

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

E.J. Pugh,

Milk Kovic,

Susan Rogers Cooper

03 September 2015

Serial Offenders

by Janice Law

Like most mystery fans, I have my favorites, characters I willingly read about time and again. Indeed, what lover of the genre wouldn’t like just one more Sherlock Holmes story or another vintage appearance from Lord Peter Whimsy or Adam Dalgliesh? Familiarity breeds contentment for the reader. The writer is another breed of cat.

Writers enjoy variety, new challenges, new plots, new directions, and perhaps for that reason even wildly successful mystery writers have sometimes had complicated feelings about their heroes and heroines. Demands for another helping of the same can arouse a homicidal streak – of the literary sort. Thus Conan Doyle sent Holmes over the Reichenback Falls and Henning Mankell gave Wallander not one, but two deadly illnesses. Agatha Christie wrote – then stored– Curtain, Poirot’s exit, at the height of her powers, while Dorothy Sayers, faced with either killing off or marrying off Lord Peter, mercifully opted for the latter. He was never the same in any case.

During my career, now longer than I like to mention, I’ve twice created serial characters, each begun as a one off. Anna Peters was never projected to live beyond The Big Payoff and my second novel used other characters entirely. Alas, Houghton Mifflin, my publisher at the time, was not enthralled, and the new novel was destined to be unlucky. Bought by Macmillan – or so I thought – the deal fell through when the entire mystery division was folded.

Back to Miss Peters, as she was then. Nine more books followed. They got good reviews and foreign translations and sold modestly well, although not ultimately well enough for the modern publishing conglomerate. I did learn one thing I’ll pass on to those contemplating a mystery series: don’t age your character.

Sure, aging a character keeps the writer from getting bored, but in five years, not to mention ten or twenty years down the road, you’re getting long in the tooth and so is your detective. Poor Anna got back trouble and was getting too old for derring do. I was faced with killing her, retiring her, or turning her into Miss Marple.

I chose to have her sell Executive Security, Inc. and retire ( some of her adventures are still available from Wildside Press). I imagined her sitting in on interesting college courses and wondered about a campus mystery. But I was teaching college courses myself at the time, and a campus setting sounded too much like my day job.

For at least a decade (actually, I suspect two) I stayed away from series characters. I published some contemporary novels with strong mystery elements and lots of short stories. I liked those because I didn’t need to love the assorted obsessives and malcontents that populated them. I just needed to like them enough for 10-14 pages worth.

Then came Madame Selina, a nineteenth century New York City medium, whose adventures were narrated by her assistant, a boy straight out of the Orphan Home named Nip Tompkins. Once again, I figured a one off, but a suggestion from fellow Sleuthsayer Rob Lopresti that she’d make a good series character led me write one more – pretty much just to see if he was wrong.

That proved lucky, as she has inspired in nine or ten stories, all of which have appeared or will appear in Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Thank you, Rob. However, there is a season for all things, and having explored many of the key issues of the nineteenth century with Madame Selina and Nip, I am beginning to tire of mysteries that can be wrapped up with a seance. That, by the way, gets harder each time out.

What to do? I’m not so ruthless as to kill off a woman who’s worked hard for me. But as she’s observed herself, times are changing and the Civil War, so horrible but so conducive to her profession, is now a decade past. As you see, I learned nothing from my experience with Anna Peters, as both Madame and Nip have continued to age.

I don’t think I’ll marry her off, either, although she knows a rich financier who might fill the bill. Instead, I think I’ll let her sell her townhouse and retire, perhaps to one of the resorts she favors, Saratoga or, better because I know the area, Newport, where she will take up gardening and grow prize roses or dahlias.

As for Nip, I’ve already picked his profession. Snooping for Madame Selina has given him every skill he needs to be a newspaperman in the great age of Yellow Journalism. Will the now teenaged Nip show up in print again?

We’ll see.

Writers enjoy variety, new challenges, new plots, new directions, and perhaps for that reason even wildly successful mystery writers have sometimes had complicated feelings about their heroes and heroines. Demands for another helping of the same can arouse a homicidal streak – of the literary sort. Thus Conan Doyle sent Holmes over the Reichenback Falls and Henning Mankell gave Wallander not one, but two deadly illnesses. Agatha Christie wrote – then stored– Curtain, Poirot’s exit, at the height of her powers, while Dorothy Sayers, faced with either killing off or marrying off Lord Peter, mercifully opted for the latter. He was never the same in any case.

|

| first POD for Anna. My design |

Back to Miss Peters, as she was then. Nine more books followed. They got good reviews and foreign translations and sold modestly well, although not ultimately well enough for the modern publishing conglomerate. I did learn one thing I’ll pass on to those contemplating a mystery series: don’t age your character.

Sure, aging a character keeps the writer from getting bored, but in five years, not to mention ten or twenty years down the road, you’re getting long in the tooth and so is your detective. Poor Anna got back trouble and was getting too old for derring do. I was faced with killing her, retiring her, or turning her into Miss Marple.

I chose to have her sell Executive Security, Inc. and retire ( some of her adventures are still available from Wildside Press). I imagined her sitting in on interesting college courses and wondered about a campus mystery. But I was teaching college courses myself at the time, and a campus setting sounded too much like my day job.

|

| Wildside edition, last Anna Peters |

Then came Madame Selina, a nineteenth century New York City medium, whose adventures were narrated by her assistant, a boy straight out of the Orphan Home named Nip Tompkins. Once again, I figured a one off, but a suggestion from fellow Sleuthsayer Rob Lopresti that she’d make a good series character led me write one more – pretty much just to see if he was wrong.

That proved lucky, as she has inspired in nine or ten stories, all of which have appeared or will appear in Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Thank you, Rob. However, there is a season for all things, and having explored many of the key issues of the nineteenth century with Madame Selina and Nip, I am beginning to tire of mysteries that can be wrapped up with a seance. That, by the way, gets harder each time out.

What to do? I’m not so ruthless as to kill off a woman who’s worked hard for me. But as she’s observed herself, times are changing and the Civil War, so horrible but so conducive to her profession, is now a decade past. As you see, I learned nothing from my experience with Anna Peters, as both Madame and Nip have continued to age.

I don’t think I’ll marry her off, either, although she knows a rich financier who might fill the bill. Instead, I think I’ll let her sell her townhouse and retire, perhaps to one of the resorts she favors, Saratoga or, better because I know the area, Newport, where she will take up gardening and grow prize roses or dahlias.

As for Nip, I’ve already picked his profession. Snooping for Madame Selina has given him every skill he needs to be a newspaperman in the great age of Yellow Journalism. Will the now teenaged Nip show up in print again?

We’ll see.

13 August 2015

No Sex, Please, We're Skittish

by Eve Fisher

by Eve Fisher

"If you mention sex at an AA meeting, even the non-smokers light up."

--Father Tom, "Learning to Live With Crazy People"

And so do a lot of mystery writers and readers. There are those who write and/or love cozies, and want everything as asexual as they think Agatha Christie was. Except, of course, that if you actually read your Agatha Christie, there's a lot of hot stuff going on: In AT BERTRAM'S HOTEL, Ladislaw Malinowski is sleeping with both Elvira Blake and her mother Bess Sedgwick, and that fact alone is one of the major drivers of the plot. In SAD CYPRESS, Roddy Welman's sudden, overwhelming attraction to Mary Gerrard makes everything homicidal possible. And, in at least three novels, a man's lust for one woman, combined with his lust for money, makes it possible for him to marry and murder a rich wife.

"If you mention sex at an AA meeting, even the non-smokers light up."

--Father Tom, "Learning to Live With Crazy People"

|

| Agatha Christie |

And so do a lot of mystery writers and readers. There are those who write and/or love cozies, and want everything as asexual as they think Agatha Christie was. Except, of course, that if you actually read your Agatha Christie, there's a lot of hot stuff going on: In AT BERTRAM'S HOTEL, Ladislaw Malinowski is sleeping with both Elvira Blake and her mother Bess Sedgwick, and that fact alone is one of the major drivers of the plot. In SAD CYPRESS, Roddy Welman's sudden, overwhelming attraction to Mary Gerrard makes everything homicidal possible. And, in at least three novels, a man's lust for one woman, combined with his lust for money, makes it possible for him to marry and murder a rich wife.

Then there's the noir crowd:

“It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.”

― Raymond Chandler, FAREWELL, MY LOVELY

“I loved her like a rabbit loves a rattlesnake.”

― James M. Cain, DOUBLE INDEMNITY

Brigid O'Shaughnessy: “I haven't lived a good life. I've been bad, worse than you could know.”

Sam Spade: “You know, that's good, because if you actually were as innocent as you pretend to be, we'd never get anywhere.”

― Dashiell Hammett, THE MALTESE FALCON

In noir, EVERYTHING is about sex. That and greed. But mostly sex, and often violent sex. (Prime examples are probably the "rip me" scene of James M. Cain's THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE - and Mickey Spillane's VENGEANCE IS MINE, in which - and I think it's the first chapter - he beats a woman before having his way with her and she loves it all.) The noir guys all moon over the virgins (Walter Huff over his victim's daughter; Mike Hammer over Velda), but the women who obsess them are anything but. And so of course they hurt them, twist them, torture them, betray them, all of the above. Truth is, after a long day in noir-land, you want to yell at them, "Try somewhere else besides a bar to meet women! Buy the girl some flowers! Try to stay sober for ten minutes!" but it's all a waste of breath. (Except, apparently, to Nick Charles who got a clue and a rich wife.)

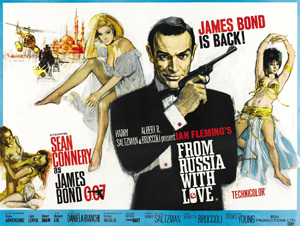

And spies...

Spy stories, of course, depend on global locales, tech wizardry, constant weapons, supervillains, and a high body count for both sex and death. Women, women, women, of all ethnicities, although Russian spies are a perennial favorite. (Is it the accent, or the idea of nudity and fur?) I just read a novel in which the male American spy and the female Russian spy were mutually obsessed, madly, madly in love/lust/etc., to the point where I really thought that the cover should be of her holding him against her exceptionally large chest, hair flowing like a female Fabio... Anyway, sex drives these plots as well, no matter what the spy or the supervillain think, because - besides providing objects of rescue, thus securing another reason for the ensuing sex - 90% of the time at least one of those women is going to save the male spy from certain death. The game is to figure out which one by, say, page five.

Horror. Sex = death. The survivor's a virgin. What more can I say?

So, to all of those who say that mysteries are all about cerebral detection, and that there isn't much place for sex in them - WHAT ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT?

As Oscar Wilde once said, “Everything in the world is about sex except sex. Sex is about power.”

You could look it up...

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

cosies,

Dashiell Hammett,

Halloween,

James Bond,

James M. Cain,

Mickey Spillane,

novels,

sex,

spy,

thrillers

07 May 2015

Pagliacci, or, Killing Your Lover is as Old as the Hills

by Eve Fisher

I went to the opera last weekend - The Met Live in HD at the Sioux Falls Century 14, big screen, great sound, and subtitles, what more could you ask for? They were showing Pagliacci. Now I'd heard about that opera all my life - everything from people on the old Ed Sullivan show singing their guts out to an Elmer Fudd parody. But I'd never seen it, so off I went, and enjoyed it a lot. Good old drama: jealousy, threats, attempted rape, betrayal, adultery and murder. What's not to like? Plus a play-within-a-play (which I am always a sucker for).

I went to the opera last weekend - The Met Live in HD at the Sioux Falls Century 14, big screen, great sound, and subtitles, what more could you ask for? They were showing Pagliacci. Now I'd heard about that opera all my life - everything from people on the old Ed Sullivan show singing their guts out to an Elmer Fudd parody. But I'd never seen it, so off I went, and enjoyed it a lot. Good old drama: jealousy, threats, attempted rape, betrayal, adultery and murder. What's not to like? Plus a play-within-a-play (which I am always a sucker for). The plot is simple: Act One: Traveling players, commedia dell'arte, arrive in a small Sicilian town, and set up shop. Canio (who plays the clown Pagliacci) is married to the beautiful Nedda (who plays the romantic heroine Columbine). The foreshadowing was the joshing about how (on stage) Columbine cuckolds Pagliacci every night with Arlecchino (Harlequin), and Canio said, hey what's on stage is fine, but in real life, I'd kill her. Cue the dramatic music, and they did. On comes the big thug Tonio (who plays Taddeo, a servant in the play-within-a-play), who wants Nedda and tries to rape her. She drives him off with a whip and he vows revenge. So he overhears and then oversees Nedda meeting up with her real lover, Silvio. He goes off, tells Canio, who gets drunk and weeps his aria, "I Pagliacci" while he puts on his white clown make-up.

Act Two: The Harlequinade, as Columbine gets ready for her tryst with Arlecchino. Taddeo wants her, she drives him off. Pagliacci arrives - but Canio/Pagliacci is murderously drunk and playing for real. (The audience, bloodthirsty as they come, is enthralled by his realism.) He chases her around the stage, they fight, and he stabs her to death. With her dying breath she calls "Silvio!" and, as Silvio fights his way up onto the stage, Canio/Pagliacci grabs him and stabs him to death, too. And then turns to the audience and cries, "La commedia è finita!" – "The comedy is finished!" Short, sweet, violent.

Pagiliacci, Cavallere Rusticana, and other operas were all part of the versimo movement of the late 1800's. Naturalism! Realism! Lots of violence! Lots of sex! Bodies piled up on the stage! (like that hadn't been done before - hadn't they ever noticed the Shakespearean body count?) And, of course, everyone is no good. Very much like film noir. The literature of the day was the same: whenever you want a good, depressing time among adulterers, thieves, murderers, whores and corrupt politicians, try Emile Zola's brilliant, harrowing, brutal Therese Raquin, Nana, and La Cousine Bette.

Pagiliacci, Cavallere Rusticana, and other operas were all part of the versimo movement of the late 1800's. Naturalism! Realism! Lots of violence! Lots of sex! Bodies piled up on the stage! (like that hadn't been done before - hadn't they ever noticed the Shakespearean body count?) And, of course, everyone is no good. Very much like film noir. The literature of the day was the same: whenever you want a good, depressing time among adulterers, thieves, murderers, whores and corrupt politicians, try Emile Zola's brilliant, harrowing, brutal Therese Raquin, Nana, and La Cousine Bette. But if that wasn't enough excitement for you - not enough sex, not enough violence, not enough B&D, S&M - you went to the Grand Guignol, where the old tradition of violence on stage was revived. Blood Feast, eat your heart out. Even Titus Andronicus didn't quite reach the levels of violence porn that the Grand Guignol did in its theater on the Rue Pigalle. From 1897 to 1962, they presented such upscale entertainment as Andre de Lorde's:

|

| Grand Guignol, 1932 |

- Le Laboratoire des Hallucinations: When a doctor finds his wife's lover in his operating room, he performs a graphic brain surgery rendering the adulterer a hallucinating semi-zombie. Now insane, the lover/patient hammers a chisel into the doctor's brain.

- Un Crime dans une Maison de Fous: Two hags in an insane asylum use scissors to blind a young, pretty fellow inmate out of jealousy.

- L'Horrible Passion: A nanny strangles the children in her care. (Synopses thanks to Wikipedia.)

(On the other hand, even the Grand Guignol didn't reach the heights of ancient Rome, where wealthy diners could and were treated to the entertainment of live gladiator contests, and theatergoers would be treated, in "The Death of Hercules", to an ending that included condemned criminal being burned to death in front of them. Humans do love violence porn...)

And they also love magic, dance, and romance. Which is also at the heart of Pagliacci. The Harlequinade that Canio and Nedda perform in Act 2 is straight from the commedia dell'arte, a staple and source of European entertainment for centuries, which always involved romance and sometimes murder. Characters from the commedia show up in Mozart operas, Shakespearean plays, and innumerable other operas and ballets. And mysteries: Sir Peter Wimsey dressed as Harlequin for half the plot of Murder Must Advertise, and Agatha Christie used the commedia over and over again as a trope or theme or a plot point, and at one point even a character - Harley Quin, who appeared in at least a dozen short stories.

And they also love magic, dance, and romance. Which is also at the heart of Pagliacci. The Harlequinade that Canio and Nedda perform in Act 2 is straight from the commedia dell'arte, a staple and source of European entertainment for centuries, which always involved romance and sometimes murder. Characters from the commedia show up in Mozart operas, Shakespearean plays, and innumerable other operas and ballets. And mysteries: Sir Peter Wimsey dressed as Harlequin for half the plot of Murder Must Advertise, and Agatha Christie used the commedia over and over again as a trope or theme or a plot point, and at one point even a character - Harley Quin, who appeared in at least a dozen short stories.The original commedia dell'arte was all about lovers (innamorate) who wanted to marry, but were hindered by elders (vecchio) and helped by servants (zanni). In the old companies (old being 1500-1700s) there would be 10 characters: two vecchi (old men), four innamorati (two male/female couples, one noble or at least middle class, the other lower class or downright clowns), two zanni, a Captain and a servetta (serving maid). That gave plenty of characters to interfere with the two classes of lovers.

|

| Papageno and Papagena |

BTW, this structure of thwarted/thwarting/attempting to thwart lovers, operating on two levels, is an old plot device. In "As You Like It", Rosalind and Orlando, the noble lovers, are balanced off by Touchstone and Audrey, the comic relief. In "The Magic Flute", the noble lovers Tamino and Pamina are balanced by Papageno and Papagena. In Anthony Trollope's "Can You Forgive Her?" there's a series of triangles: in the noble group, Plantagenet Palliser and Burgo Fitzgerald vie for Lady Glencora (PP's wife), in the middle-class group, George Vavasor and John Gray vie for Alice Vavasor, and in the lower-class group, Captain Bellfield and Squire Cheesacre vie for the Widow Greenow, and the latter three (the most hilarious) are straight out of the classic comic commedia dell'arte: smart woman, miser, and the captain.Anyway, the characters and plot lines went all the way back to ancient Greek and Roman plays, and were continually updated and remade. The major characters were:

Harlequin (a/k/a Arlecchino) - in love with and the beloved of Columbine. Originally, Harlequin - and this is what makes him very interesting - was an emissary of the Devil, and was played with a red and black mask and the motley costume that the demon(s) used to wear in the old Medieval Mystery Plays. An athletic, acrobatic trickster, he was transformed over time into a more romantic figure. But he remained a magician, and he could either be hilariously clever or diabolically deadly... Even to Columbine...

Harlequin (a/k/a Arlecchino) - in love with and the beloved of Columbine. Originally, Harlequin - and this is what makes him very interesting - was an emissary of the Devil, and was played with a red and black mask and the motley costume that the demon(s) used to wear in the old Medieval Mystery Plays. An athletic, acrobatic trickster, he was transformed over time into a more romantic figure. But he remained a magician, and he could either be hilariously clever or diabolically deadly... Even to Columbine...Columbine - beautiful, witty, often the wife of Pierrot (Pagliacci), but always in love with Harlequin, and always the smartest person in the room. She was usually the only person seen on stage without a mask or clown make-up.

Pierrot (a/k/a Pagliacci) - a clown who somehow got Columbine to marry him. In the 18th century, he (almost) gave up Columbine, because he had his own Pierrette. But Pierrette often died young, leaving Pierrot always, always grieving - the sad clown.

Scaramouche - a clown, but "sly, adroit, and conceited". Later he became swashbuckling, mainly because of the Rafael Sabantini novel in which a swashbuckling nobleman's bastard hides out (in a plot twist) in a commedia troupe. BTW, the novel "Scaramouche" opens with the great line: "He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad."

Pulcinella a/k/a Punchinella a/k/a Punch (as in Punch and Judy) - a mean, crafty, hunchbacked clown who pretends to be stupider than he really is. He is also incredibly violent: with his "slapstick" (a stick as long as himself), he beats the living crap out of everyone, especially Judy.

Pulcinella a/k/a Punchinella a/k/a Punch (as in Punch and Judy) - a mean, crafty, hunchbacked clown who pretends to be stupider than he really is. He is also incredibly violent: with his "slapstick" (a stick as long as himself), he beats the living crap out of everyone, especially Judy.As it says in the novel Mrs. Miniver: "[Punch's] baby yelled and was flung out of the window; Judy scolded and was bludgeoned to death; the beadle, the doctor, and the hangman tried in turn to perform their professional duties and were outrageously thwarted; Punch, cunning, violent and unscrupulous, with no virtues whatever except humour and vitality, came out triumphant in the end. And all the children, their faces upturned in the sun like a bed of pink daisies, laughed and clapped and shouted with delight." Perfect childhood fun.

|

| "The Last of the Summer Wine" - Foggy's in back |

Il Capitano - The soldier, who boasts constantly (while being an arrant coward), knows everything, and is always getting into fights he has no real intention of fighting. Il Capitano is still a major stock character in everything from Dickens (Nathaniel Winkle in the Pickwick Papers), Agatha Christie (think of Major Palgrave in "A Caribbean Mystery"), E. F. Benson's Major Benjy, Flashman, and Foggy in the long-running comedy, "Last of the Summer Wine".

Actually, as I think about it, these are all stock characters, still used all the time. You could say that Harlequin today is someone like Jack Reacher, Patrick Jane, Spenser, etc., and Columbine is Emma Peel, Elizabeth Swann, perhaps even Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Make your own list. But keep your eyes open: the cast of the commedia dell'arte shows up in all sorts of times and places. And where they come... death often follows.

29 April 2015

The Golden Age of Murder

A special treat today. I lucked into an advance copy of a terrific nonfiction book and when I realized the official release date was this week I invited the author to tell us about it. Martin Edwards is the author of eighteen novels, and eight non-fiction books. Plus he's edited two dozen anthologies. He has won the Crime Writers' Association Dagger and the Margery Allingham prize for short stories. I highly recommend his book, which has taught me a lot about the writers of the so-called Golden Age, and especially WHY they wrote what they did. — Robert Lopresti

The Golden Age of Murder

by Martin Edwards

Crime fans know better than anyone that appearances can be deceptive. And that idea is at the heart of The Golden Age of Murder, my just-published study of the British crime novelists who dominated the genre between the two world wars. There’s a widely held view that those writers were cosy, conventional folk who wrote cosy and conventional books. But the more I researched the men and women who wrote the best Golden Age mysteries, the more I became convinced that the truth was rather different – and much more enthralling.

I write crime novels set in the here and now, but I’ve always loved the ingenious traditional murder mysteries. Like so many other people around the world, my introduction to adult fiction was through the books of Agatha Christie, a writer whose work I still love. From her I graduated to Dorothy L. Sayers, and then other great names of the era, such as Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, and Anthony Berkeley.

Later I discovered that those writers, and a good many others whose books I enjoyed, were members of the Detection Club, a select and rather mysterious organisation which exists to this day. Led by Berkeley (who founded the Club) and Sayers, members yearned to raise the standard of crime writing, and strove to ensure that their own work was fresh and inventive.

Sayers, for example, wanted to take the genre in a new direction, and with a fellow Club member, Robert Eustace, she produced The Documents in the Case, an ambitious book in which Lord Peter Wimsey did not appear. Writing as Francis Iles, Berkeley became the standard-bearer for the novel of psychological crime – the first Iles book, Malice Aforethought, remains a genre classic, and the second, the dark and deeply ironic Before the Fact, was filmed by Alfred Hitchcock. But Club members also remained true to the game-playing spirit of the times. They collaborated in “round-robin” mysteries such as The Floating Admiral, each writing a chapter in turn. The book enjoyed critical and commercial success, which was repeated when it was republished recently

I became fascinated by the relationships between the writers – long before the days of blogs, Twitter and Facebook, the Detection Club was a remarkable social network. Seven years ago, I was elected to membership of the Club myself, and was asked to look after the Club’s archives. But since very little had been retained over the years, really I had to become a detective, finding out about the Club’s history. I talked to experts across the world, and travelled around, tracking down descendants of those early Club members.

Fresh mysteries kept arising, crying out for a solution. The Club’s members obsessed about their personal privacy, and many of them hugged dark and disturbing secrets. One pioneering novelist even made diary entries in an unbreakable code, so nobody could decipher what was in his mind. Clever people, well-versed in the art of mystification, Detection Club members deployed their skills to obscure the trail for anyone seeking to learn more about them. Agatha Christie’s controversial eleven-day disappearance in 1926 is by far the most high profile of the numerous disasters that befell Club members, and affected their writing as well the future course of their lives.

In The Golden Age of Murder, I’ve set out to solve the mysteries of the writers who in many ways were responsible for inventing the modern detective novel. It’s been an engrossing quest, and my greatest hope is that it will encourage people who have, in the past, been dismissive of traditional detective fiction to think again. Of course, plenty of bad books were written in the Golden Age, as in every age, but the best work of the time was exhilarating, innovative - and unforgettable.

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

Dorothy Sayers,

Lopresti,

Martin Edwards

11 April 2015

Go Away, Space Angel! I'm Trying to Write Crime

by Melodie Campbell

A funny thing happened on the way to the crime book: it

became a comic sci-fi spy novella.

That’s the frustrating thing about being a fiction

writer. Sometimes you don’t pick your

characters – they pick you.

I was sitting at my desk, minding my own business, when…no,

that’s not how it happened.

It was far worse.

“Write a spy novel!” said the notable crime reviewer (one of

that rare breed who still has a newspaper column.) We were yapping over a few drinks

last spring. “A funny one. Modesty

Blaise meets Maxwell Smart, only in modern day, of course.”

“Sure!” I said, slurping Pinot by the $16 glass. After all, crime is my thing. I was weaned on Agatha Christie. I had 40 crime short stories and 5 crime books published to date. This sounded like the perfect 'next series' to write.

And I intended to.

Truly I did. I tried all summer.

I even met with a former CSIS operative to get the scoop on the spy biz (think

CIA, but Canada – yes, he was polite.)

Wrote for two months solid. The

result was…kinda flat. (I blame the

Pinot. Never take up a book-writing dare

with a 9 oz. glass of Pinot in your hand. Ditto good single malt. THAT resulted in a piece of erotica that shall

forever be known under a different name…

But I digress.)

Back to the crime book.

I started to hate it.

Then, in the middle of the night (WHY does this always

happens in the middle of the night?) a few characters started popping up. Colourful, fun characters, from another time.

They took my mind by siege. “GO AWAY,” I

told them. “I’m trying to write a crime book!”

They didn’t. It was a

criminal sit-in. They wouldn’t leave

until I agreed to write their tale.

So the modern day spy novel became a futuristic spy novel. Modesty Blaise runs a bar on a space-station,

so to speak. Crime in Space, with

the kind of comedy you might expect from a descendent of The Goddaughter.

Two more months spent in feverish writing. Another two in rewrites. Then another, to convince my publisher that

the project had legs.

CODE NAME: GYPSY MOTH

is the result. Yet another crossing the

genres escapade.

Written by me, and a motley crew of night visitors.

Now hopefully they will keep it down in there so I can

sleep.

CODE NAME: GYPSY MOTH

“Comedy and Space Opera – a blast to

read” (former editor Distant Suns magazine)

“a worthy tribute to Douglas

Adams” (Cathy Astolfo, award-winning author)

It isn't easy being a female barkeep in the final frontier...especially when you’re also a spy!

Nell Romana loves two things: the Blue Angel Bar, and Dalamar, a notorious modern-day knight for hire. Too bad he doesn't know she is actually an undercover agent. When Dalamar is called away on a routine job, Nell uncovers a rebel plot to overthrow the Federation. She has to act fast and alone.

Then the worst happens. Her cover is blown…

The Toronto Sun called her Canada’s “Queen of Comedy.” Library Journal compared her to Janet

Evanovich. Melodie Campbell got her

start writing standup. She has over 200

publications and nine awards for fiction.

Code Name: Gypsy Moth (Imajin

Books) is her eighth book.

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

comedy,

crime,

Douglas Adams,

fiction,

Get Smart,

humor,

Maxwell Smart,

Modesty Blaise,

novels,

Sherlock Holmes,

space opera,

spy,

suspense

25 January 2015

Slip Sliding Away?

by Dale Andrews

[The Doctor] gave me the route map: loss of memory, short- and long-term, the disappearance of single words -- simple nouns might be the first to go -- then language itself, along with balance, and soon after, all motor control, and finally the autonomous nervous system. Bon voyage!

Atonement: A Novel

Ian McEwan

Over the holidays I read several mystery novels, each set in Florida or the Gulf Coast, all in a row. I don’t know why I did this -- maybe the gray skies over Washington, D.C. and the promise (threat?) of more winter on the horizon had something to do with it, or maybe it was just a simple reaction to my impending return to SleuthSayers and the prospect of sharing space on a new day with my friend and inveterate Floridian Leigh. More on those Florida books later -- perhaps next month.

But after that steady southern diet I started to feel a little swampy, which led me to Ian McEwan’s Atonement in search of something different. A great book, by the way. And in it the above quote, from an author character who, near the end of Atonement, confronts the onset of dementia, struck a chord. Confronting and dealing with dementia in the context of mystery novels has been a recurring theme, both lately and historically.

But after that steady southern diet I started to feel a little swampy, which led me to Ian McEwan’s Atonement in search of something different. A great book, by the way. And in it the above quote, from an author character who, near the end of Atonement, confronts the onset of dementia, struck a chord. Confronting and dealing with dementia in the context of mystery novels has been a recurring theme, both lately and historically.

In an earlier article discussing first person narration I referenced Alice LaPlante’s debut novel Turn of Mind, where the central character and first person narrator, Dr. Jennifer White, is an Orthopedic surgeon suffering from Alzheimer's disease. LaPlante skillfully allows the reader to know only what Jennifer knows, and the story progresses only through her distorted view. As readers we are imprisoned in her mind, a mind that Dr. White herself describes as:

This half state. Life in the shadows. As the neurofibrillary tangles proliferate, as the neuritic plaques harden, as synapses cease to fire and my mind rots out, I remain aware. An unanesthetized patient.

Another recent mystery utilizing the same technique -- a narrator disabled by dementia -- is Emma Healing’s ambitious mystery Elizabeth Is Missing. Here, too, the first person narration is by the central character, Maude, who speaks through her dementia, and all we know of the mystery at hand, and the clues to its solution, are told to us through her filter.

Tough stuff, writing a mystery under such constraints. But what about the tougher task -- writing a mystery when it is the author who is struggling with the real-life constraint? That may be precisely what Agatha Christie did when she penned her last mysteries.

I began to read Christie late, after I had exhausted all of the Ellery Queen mysteries that were out there. And that early obsession with Queen tripped me up a bit as I approached Christie. With Queen I found that I liked the later mysteries best, those from the mid-1940s on. I particularly liked the final Queen volumes, beginning with The Finishing Stroke. And that led me to a mis-step. I began reading Christie by starting with her most recent works, specifically, Postern of Fate and Elephants Can Remember. Oops.

Postern of Fate, the chronologically last book that Christie wrote, features Tommy and Tuppence Beresford. This, on its own, is a sad way to end things -- they were hardly Christie’s best detective characters. But that is not the real problem. The reader uncomfortably notes from the beginning of the book that conversations occurring in one chapter are forgotten in the next. Deductions that are relatively simple are drawn out through the course of many pages. Clues are dealt with multiple times in some instances, in others they are completely ignored. The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English, tags the work as one of Christie’s "execrable last novels" in which she "loses her grip altogether."

Elephants Can Remember, written one year earlier, fares no better. The Cambridge Guide also ranks this as one of the “execrable last novels.” More specifically, English crime writer, critic and lecturer Robert Bernard had this to say:

Another murder-in-the-past case, with nobody able to remember anything clearly, including, alas, the author. At one time we are told that General Ravenscroft and his wife (the dead pair) were respectively sixty and thirty-five; later we are told he had fallen in love with his wife's twin sister 'as a young man'. The murder/suicide is once said to have taken place ten to twelve years before, elsewhere fifteen, or twenty. Acres of meandering conversations, hundreds of speeches beginning with 'Well, …' That sort of thing may happen in life, but one doesn't want to read it.

Speaking of reading, are we perhaps reading too much into all of this? Could it just be that Christie had run out of inspiration? Younger writers (Stephen King comes to mind) display peaks and valleys in their fiction output. Could Christie have just ended in a valley? Unlikely. There is almost certainly more to Christie’s problem than just un-inspired plots.

Ian Lancashire, an English professor at the University of Toronto wondered about the perceived decline in Christie’s later novels and devised a way to put them to the test. Lancashire developed a computer program that tabulates word usage in books, and then fed sixteen of Agatha Christie’s works, written over fifty years, into the computer. Here are his findings, couched in terms of his analysis of Elephants Can Remember, and as summarized by RadioLab columnist Robert Krulwich:

When Lancashire looked at the results for [Elephants Can Remember], written when [Christie] was 81 years old, he saw something strange. Her use of words like "thing," "anything," "something," "nothing" – terms that Lancashire classifies as "indefinite words" – spiked. At the same time, [the] number of different words she used dropped by 20 percent. "That is astounding," says Lancashire, "that is one-fifth of her vocabulary lost."

But to her credit, Christie was likely battling mightily to produce Elephants and Postern. Lancaster hypothesizes as much, not only from the results of his computer analysis of vocabulary, but also based on a more subjective analysis of the plot of Elephants.

Lancashire told Canadian current affairs magazine Macleans that the title of the novel, a tweaking of the proverb "elephants never forget", also gives a clue that Christie was defensive about her declining mental powers. . . . [T]he protagonist [in the story] is unable to solve the mystery herself, and is forced to call on the aid of Hercule Poirot.

"[This] reveals an author responding to something she feels is happening but cannot do anything about," he said. "It's almost as if the crime is not the double-murder-suicide, the crime is dementia."

In any event Christie likely should have stopped while the stopping was good, which she did after Postern. Her final mysteries, Curtain and Sleeping Murder, while published in the mid-1970s, were in fact written in the 1940s.

Christie’s plight is a bit uncomfortable for aging authors (I find myself standing in the queue) to contemplate. But thankfully Christie’s road as she reached 80 is not everyone’s. Rex Stout still had the literary dash at about the same age to give us Nero Wolfe slamming that door in J. Edgar Hoover’s face in The Doorbell Rang. There, and in his final work Family Affair, written in 1975 when Stout was in his late 80s, there are certainly no apparent problems. Time’s review of Family concluded "even veteran aficionados will be hypnotized by this witty, complex mystery." I recently read Ruth Rendell’s latest work, The Girl Next Door, written during Rendell's 84th year, and it is, to use Dicken’s phrase, “tight as a drum.” Similarly, the last P. D. James work, Death Comes to Pemberley, a Jane Austen pastiche written when James was well into her 90s, received glowing reviews, most notably from the New York Times, and has already been adapted into a British television miniseries. And when James’ works were analyzed by the same computer program to which Christie’s novels were subjected, the results established that James’ vocabulary, even in her 90s, was indistinguishable from that employed in her earlier works.

So if you are both writing and contemplating the other side of middle age, watch out! But on the other hand don’t needlessly descend into gloom. Keep your fingers crossed and remember the advice of Spock, as rendered by Leonard Nimoy (also in his 80’s): Live long and prosper!

Labels:

Agatha Christie,

Dale C. Andrews,

dementia,

Ian McEwan

Location:

Chevy Chase, Washington, DC

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)