|

| Alexander Woollcott |

So I was rereading Woollcott's While Rome Burns, and - thinking of us, dear SleuthSayers and fans! - headed straight for the section "It May be Human Gore". I struck the motherlode. The following - from the chapter "By The Rude Bridge" - is one of my favorite murders of all time.

Let's just start off by saying that in September, 1929, Myrtle Adkins Bennett, Kansas City housewife, shot her husband, John G. Bennett, to death over a hand of contract bridge. Where's the mystery, you ask? Well, read on:

*********************

(From While Rome Burns.)"The Bennett killing, which occurred on the night of September 29, 1929, was usually spoken of, with approximate accuracy, as the Bridge-Table Murder. The victim was a personable and prosperous young salesman whose mission, as representative of the house of Hudnut, was to add to the fragrance of life in the Middle West. He had been married eleven years before to a Miss Myrtle Adkins, originally from Arkansas, who first saw his photograph at the home of a friend, announced at once that she intended to marry him, and then, perhaps with this purpose still in mind, recognized and accosted him a year later when she happened to encounter him on a train. That was during the war when the good points of our perfume salesman’s physique were enhanced by an officer’s uniform. They were married in Memphis during the considerable agitation of November 11, 1918. The marriage was a happy one. At least, Senator Jim Reed, who represented Mrs. Bennett in the trying but inevitable legal formalities which ensued upon her bereavement, announced in court—between sobs—that they had always been more like sweethearts than man and wife.

"On Mr. Bennett’s last Sunday on earth, these wedded sweethearts spent the day playing a foursome at golf with their friends, Charles and Mayme Hofman... After dark and after an ice-box supper at the Bennetts’, the men folk professed themselves too weary to dress for the movies, so the four settled down to a more slatternly evening of contract bridge. They played family against family at a tenth of a cent a side. With a pretty laugh, Mayme Hofman on the witness stand referred to such a game as playing for “fun stakes,” though whether this was a repulsive little phrase of her own or one prevalent in the now devitalized society of a once rugged community, I do not know.

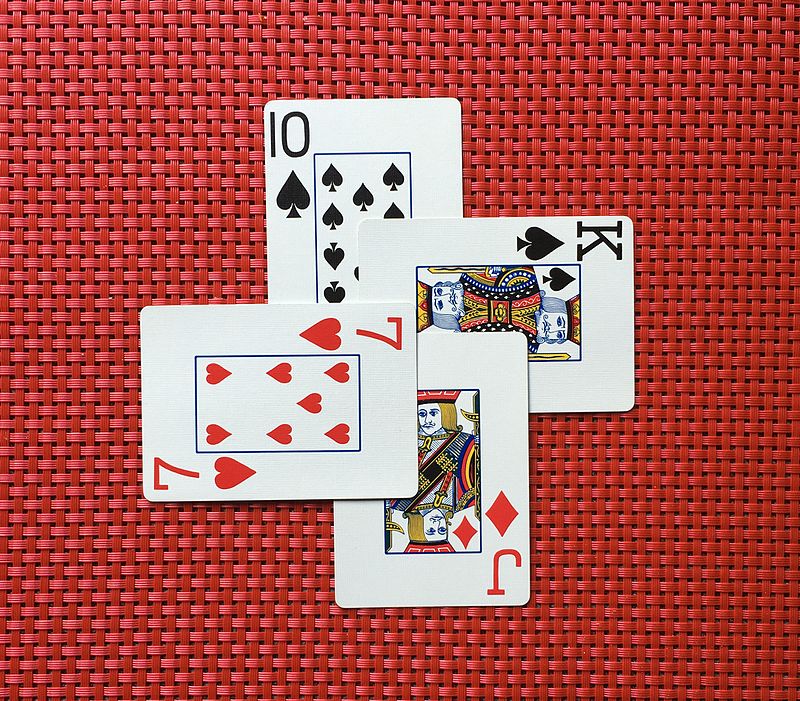

"On Mr. Bennett’s last Sunday on earth, these wedded sweethearts spent the day playing a foursome at golf with their friends, Charles and Mayme Hofman... After dark and after an ice-box supper at the Bennetts’, the men folk professed themselves too weary to dress for the movies, so the four settled down to a more slatternly evening of contract bridge. They played family against family at a tenth of a cent a side. With a pretty laugh, Mayme Hofman on the witness stand referred to such a game as playing for “fun stakes,” though whether this was a repulsive little phrase of her own or one prevalent in the now devitalized society of a once rugged community, I do not know."They played for some hours. At first the luck went against the Hofmans and the married sweethearts were as merry as grigs. Later the tide turned and the cross-table talk of the Bennetts became tinged with constructive criticism. Finally, just before midnight, the fatal hand was dealt by Bennett himself and he opened the bidding with one spade. Hofman hazarded two diamonds. Mrs. Bennett leaped to four spades. Discreet silence from Mrs. Hofman. Stunned silence from Bennett. Hofman doubled. That ended the bidding and the play began.

|

| https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/User:Newwhist |

“Myrtle put down a good hand,” she said staunchly, “it was a perfectly beautiful hand.”

"In any event, while she was dummy, Mrs. Bennett retired to the kitchen to prepare breakfast for her lord and master, who would be leaving at the crack of dawn for St. Joe. She came back to find he had been set two and to be greeted with the almost automatic charge that she had overbid. Thereupon she ventured to opine that he was, in her phrase, “a bum bridge player.” His reply to that was a slap in the face, followed by several more of the same—whether three or four more, witnesses were uncertain. Then while he stormed about proclaiming his intention to leave for St. Joe at once and while Mr. Hofman prudently devoted the interval to totting up the score, Mrs. Bennett retired to the davenport to weep on the sympathetic bosom of Mayme Hofman:

“No one but a cur would strike a woman in the presence of friends.”

|

| James Thurber, The New Yorker via Pinterest (Link) |

"He soon learned.

"There were four shots, with a brief interval after the second. The first went through the hastily closed bathroom door. The second was embedded in the lintel. The next two were embedded in Mr. Bennett, the fourth and fatal shot hitting him in the back.

"The next day the story went round the world. In its first reverberations, I noticed, with interest, that after her visit to the mortuary chapel Mrs. Bennett objected plaintively to her husband’s being buried without a pocket-handkerchief showing in his coat. To interested visitors, she would make cryptic remarks such as “Nobody knows but me and my God why I did it,” thus leaving open to pleasant speculation the probable nature of her defense.

[Seventeen months passed, and finally Woollcott asked a Kansas City friend what happened to the case?]

“Oh!” the good doctor replied, “she was acquitted. It seems it was just an unfortunate accident.”

|

| Natty couple in 1929 Wikipedia Source |

"The defense was materially aided by the exclusion on technical grounds of crucial testimony which would have tended to indicate that at the time Mrs. Bennett had told a rather different story. It was also helped no little by the defendant herself who, in the course of the trial, is estimated to have shed more tears than Jane Cowl did in the entire season of Common Clay. Even the Senator was occasionally unmanned, breaking into sobs several times in the presence of the jury. “I just can’t help it,” he replied, when the calloused prosecutor urged him to bear up.

"The Reed construction of the fatal night’s events proved subsequently important to Mrs. Bennett, in whose favor her husband had once taken out a policy to cover the contingency of his death through accident. Some months after the acquittal a dazed insurance company paid her thirty thousand dollars.

"Footnote: Protesting as I do against the short-weight reporting in the Notable British Trials series, it would ill become me to hoard for my private pleasure certain postscripts to the Bennett case which have recently drifted my way. It looked for a time as if we all might be vouchsafed the luxury of reading Myrtle’s autobiography, but this great work has been indefinitely postponed. I understand she could not come to terms with the local journalist who was to do the actual writing. That ink-stained wretch demanded half the royalties. Mrs. Bennett felt this division would be inequitable, since, as she pointed out, she herself had done all the work.

"Then it seems she has not allowed her bridge to grow rusty, even though she occasionally encounters an explicable difficulty in finding a partner. Recently she took on one unacquainted with her history. Having made an impulsive bid, he put his hand down with some diffidence. “Partner,” he said, “I’m afraid you’ll want to shoot me for this.” Mrs. Bennett, says my informant, had the good taste to faint."

************

Back to my musings:

For the more curious among us: What bridge hand could be that bad? See Snopes' reconstruction HERE.

|

| Source: https://www.rosewoodhotels.com/en/the-carlyle-new-york/gallery |

Final Note: According to Woollcott, "It was Harpo Marx who, on hearing the doctor’s hasty but spirited résumé of the case, suggested that I make use of it for one of my little articles. He even professed to have thought of a title for it. Skeptically I inquired what this might be and he answered “Vulnerable.”"

But personally, I prefer the title "Revoked."

I must look up Alexander Wolcott!

ReplyDeleteJanice, two of his books, While Rome Burns and Long, Long Ago are available on fadedpage.com.

ReplyDeleteThere's a mystery fiction connection to Woolcott. He claimed to be the inspiration for Nero Wolfe, hich Rex Stout denied, but in 1943 he was on Rex Stout's radio show, discussing the war, when he wrote "I am sick" and left the studio. Died hours later. Most likely this inspired a similar scene in Stout's And Be A Villain.

ReplyDeleteRob, I've heard that story before. From Wikipedia notes:

ReplyDelete"In September 1935 Woollcott phoned Rex and invited him to dinner at the Lambs' Club. Until then the two men had never met. Woollcott wanted to meet Rex because he had just read The League of Frightened Men and was convinced the character of Wolfe was modeled on himself." Woollcott refused to accept Stout's denials, and as their friendship grew he settled into the legend."

But yes, I'm sure Stout modeled "And Be A Villain" on Woollcott's death.