I was so awed by Disney’s television adaptation of the first Hardy Boys mystery, originally published as The Tower Treasure, that I immediately went out in search of Hardy Boys books that I could devour on my own.

Naturally, the first place I tried was the library. But when I summoned up the courage to ask the librarian where I might find the library's collection of Hardy Boy books she looked aghast. Her eyes widened, she snorted and then, looking down over the tops of those half spectacles, informed me that the Hardy Boys series was simply not the sort of book that one found in a library.

This was astonishing to me at seven. Why would the library refuse to stock an entire series of books? Particularly a popular series written for kids? But no matter. I was on a mission. I persevered.

This was astonishing to me at seven. Why would the library refuse to stock an entire series of books? Particularly a popular series written for kids? But no matter. I was on a mission. I persevered.

|

| Stix, Baer and Fuller, Clayton Missouri circa 1956 "Second floor, Books." |

The neighborhood bookstore also did not carry the Hardy Boys, and I sensed in them, too, a degree of disdain when I asked about the books. But this was the 1950s, a time when department stores were truly stores with departments. So the next time I went shopping with my parents at the neighborhood Stix, Baer and Fuller department store (a St. Louis fixture back then) I headed straight for the book department. And there they were. Row after row of hardcover Hardy Boy mysteries, each for sale for $1.00. I immediately purchased the first three books in the series, exhausting my saved allowance funds, even though my mother warned me that, at age 7, I probably would have an extremely difficult time reading them.

I didn't. As soon as we got home I wedged myself into the corner of the living room sofa and was lost in the marvelous adventures of Frank and Joe Hardy. I think that it was those books that really taught me the joy of reading for pleasure.

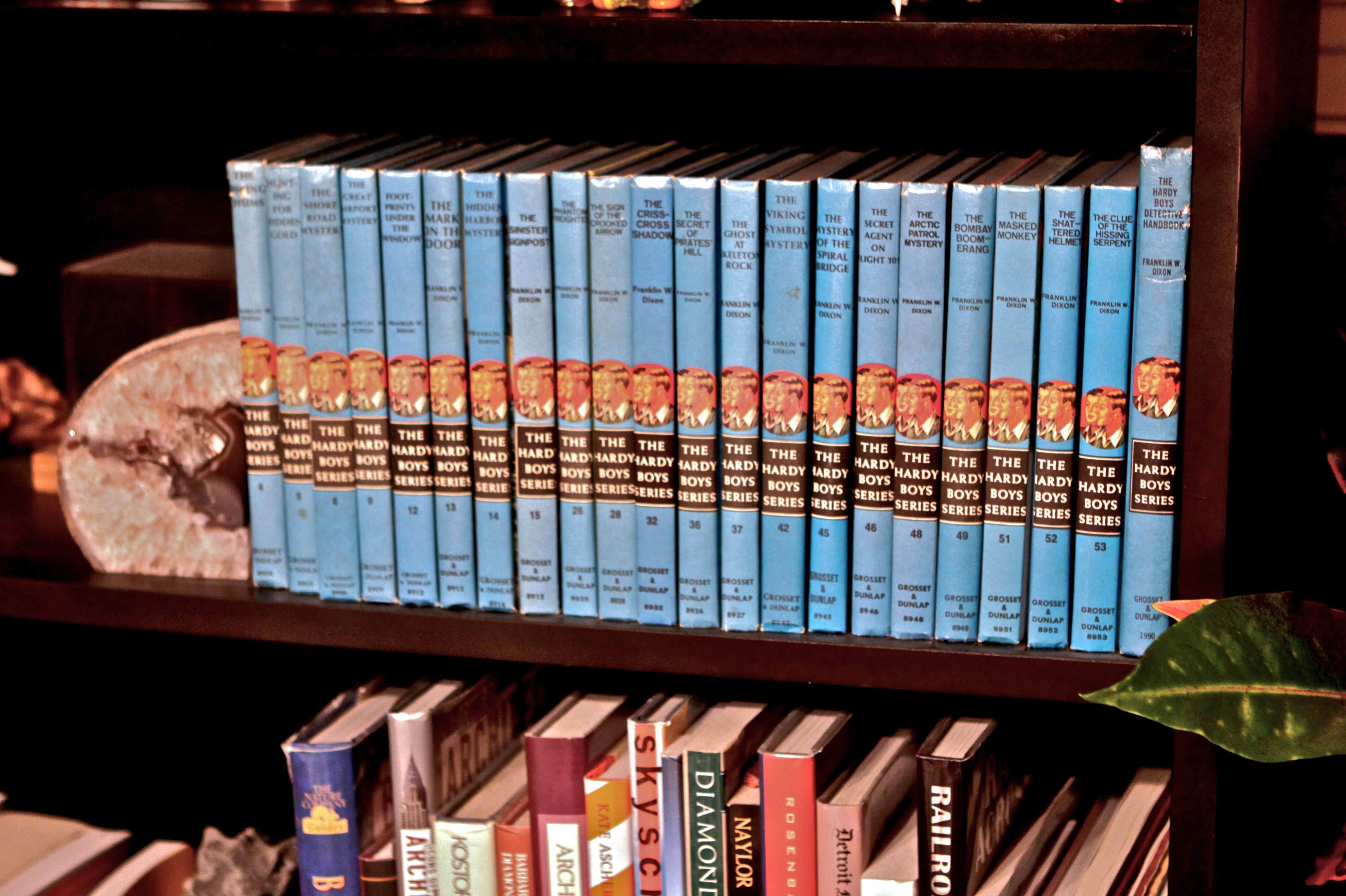

For the next several years Hardy Boy mysteries topped every one of my birthday and Christmas wish lists. But as I got deeper into the series things began to bother me. How could Frank and Joe remain, respectively, 16 and 15 years old in each mystery? And who was this “Franklin W. Dixon” who had written the marvelous series, beginning way back in the 1920s?

As time passed, like every other fan of the Hardy Boys, I began to grow up. My taste for mysteries had been whetted and more and more my collection of Hardy Boy books sat gathering dust on the bottom shelf of the bookcase as I turned to Arthur Conan Doyle, Ellery Queen and others. But I never forgot about Frank and Joe, and if asked, I would readily volunteer that my thirst for detective fiction, in fact my appetite for reading fiction, began with, and was fueled by, their exploits.

If the theme of my last article, on pseudonyms, was John Steinbeck’s admonition that “we can’t start over,” the theme of this one must be Thomas Wolfe’s “you can’t go home again.”

Have any of you tried to go back, as adults, and re-read a Hardy Boys book? Or a Nancy Drew mystery? It is only when I attempted this myself that I finally understood the librarian's aghast look as she stared down at me over her half specs when I was seven. No two ways about it, the Hardy Boys are repositories of atrocious writing.

Back in 1998 Gene Weingarten, staff writer for The Washington Post (and a very funny man) reached the same conclusion in a wonderful article chronicling his own adult-rediscovery of the works of Franklin W. Dixon:

Now, through my bifocals, I again confronted The Missing Chums [which is the fourth volume of the series]. Here is how it begins:

"You certainly ought to have a dandy trip."

"I'll say we will, Frank! We sure wish you could come along!"

Frank Hardy grinned ruefully and shook his head. . . .

"Just think of it!" said Chet Morton, the other speaker. "A whole week motorboating along the coast. We're the lucky boys, eh Biff?"

"You bet we're lucky!"

"It won't be the same without the Hardy Boys," returned Chet.

Dispiritedly, I leafed through other volumes. They all read the same. The dialogue is as wooden as an Eberhard Faber, the characters as thin as a sneer, the plots as forced as a laugh at the boss's joke, the style as overwrought as this sentence. Adjectives are flogged to within an inch of their lives: "Frank was electrified with astonishment." Drama is milked dry, until the teat is sore and bleeding: "The Hardy boys were tense with a realization of their peril." Seventeen words seldom suffice when 71 will do:

"Mrs. Hardy viewed their passion for detective work with considerable apprehension, preferring that they plan to go to a university and direct their energies toward entering one of the professions; but the success of the lads had been so marked in the cases on which they had been engaged that she had by now almost resigned herself to seeing them destined for careers as private detectives when they should grow older."

Physical descriptions are so perfunctory that the characters practically disappear. In 15 volumes we learn little more than this about 16-year-old Frank: He is dark-haired. And this about 15-year-old Joe: He is blond.

These may be the worst books ever written.

Gene Weingarten captures perfectly the surprise and disappointment that a returning reader encounters when cherished childhood memories are found to have been premised not on greatness but on hack mediocrity. His reaction (and my own) to discovering, as an adult, the shortcomings of the mystery series we loved as children is not uncommon. It is, in fact, almost universal among those who attempt to “go home again” to those Franklin W. Dixon volumes that highlighted our childhood.

When Benjamin Hoff, bestselling author of The Tao of Pooh re-read the Hardy Boys as an adult he felt compelled, like Pygmalion, to try to set things right. Mr. Hoff went so far as to re-write the second book in the series, The House on the Cliff and published his re-imagined story, re-titled The House on the Point, complete with two appended essays analyzing the original Franklin W. Dixon work. A noble attempt to re-build that childhood home that he had returned to only to find in shambles.

But ultimately you can’t do it. Here is what Austin Chronicle reviewer Tim Walker wrote of Hoff’s futile attempt:

But ultimately you can’t do it. Here is what Austin Chronicle reviewer Tim Walker wrote of Hoff’s futile attempt:

Benjamin Hoff's loving tribute to his boyhood heroes the Hardy Boys recalls The House on the Cliff, the second installment of the original series. As one would hope, Hoff's book is executed with a literary sensibility far superior to the original's. While the narrative seldom attains the gentle flow of Hoff's The Tao of Pooh, its many historical and physical details lend fine verisimilitude, and Hoff has drawn its characters with a real human depth that is absent from the stories that have been selling strongly for 75 years.

[But] any Hardy Boys tribute will run up against the thorny fact of the originals' bad writing. The plots make little sense, the wooden dialogue is in some way an improvement on the cardboard-cutout characters, and the boys themselves take on lethal dangers with barely a second thought in an otherwise sober setting that doesn't make the fantasy element of the book clear. . . . Hoff's book is worth reading, but if it fires you up to re-read the Hardy Boys, understand that you'll be doing it only for nostalgia.

|

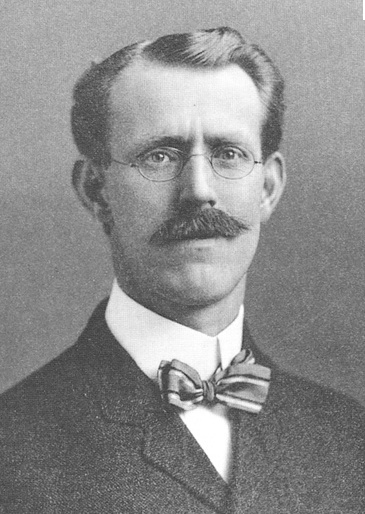

| Edward Stratemeyer |

So. Who was this Franklin W. Dixon, and how could he have produced such a popular but, at base, awful series of books? The answer to that question is pretty much common knowledge now.

In fact, there never was a “Franklin W. Dixon.” The name is a pseudonym utilized by a number of contract writers who produced the Hardy Boys series and the Nancy Drew series ("written" by the equally fictional Carolyn Keene), for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a self-proclaimed “packager’ of books established in 1905 to provide reading material for young adults (and to make money along the way). The syndicate was the brainchild of Edward Stratemeyer, who wrote the first Bobbsey Twin book before realizing that producing series of childrens’ books under different pseudonyms, ghostwritten by hired writers, would play better in the marketplace. This assumption proved entirely correct. By 1930, the Stratemeyer Syndicate had sold over 5 million copies of its ghosted books and basically controlled the U.S. market for childrens’ books.

In fact, there never was a “Franklin W. Dixon.” The name is a pseudonym utilized by a number of contract writers who produced the Hardy Boys series and the Nancy Drew series ("written" by the equally fictional Carolyn Keene), for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a self-proclaimed “packager’ of books established in 1905 to provide reading material for young adults (and to make money along the way). The syndicate was the brainchild of Edward Stratemeyer, who wrote the first Bobbsey Twin book before realizing that producing series of childrens’ books under different pseudonyms, ghostwritten by hired writers, would play better in the marketplace. This assumption proved entirely correct. By 1930, the Stratemeyer Syndicate had sold over 5 million copies of its ghosted books and basically controlled the U.S. market for childrens’ books.

One of Stratemeyer’s greatest successes was the Hardy Boys. The original series consisted of 58 installments, and was followed by several related series, re-imagining Frank and Joe in more modern times. The latest, The Hardy Boys Adventures, was launched in 2013, and new volumes are currently being published in that series. From the date of the original publication of The Tower Treasure in 1927 there has never been a year when the Hardy Boys series was out of print.

|

| Leslie McFarlane |

McFarlane, like all subsequent Hardy Boys authors, toiled in secrecy in return for a pittance. He was required to sign a confidentiality agreement obligating him never to divulge his authorship of Franklin W. Dixon books. In return he, and the later writers, were paid “princely” sums ranging from $75.00 to $100 per book in the early years to produce new installments in the series, each rigidly premised on outlines supplied by the Stratemeyer Syndicate. The Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew and Tom Swift series were all written under the same arrangements. Attempts by McFarlane and subsequent authors to vary from the script, or to breathe life into the characters reportedly were dealt with quickly and ruthlessly by the editorial pens of the syndicate.

Did all of this grate on McFarlane? You bet. Gene Weingarten’s article collects and analyzes entries from the detailed diaries that McFarlane kept over the years.

Did all of this grate on McFarlane? You bet. Gene Weingarten’s article collects and analyzes entries from the detailed diaries that McFarlane kept over the years.

“The Hardy Boys" [series] is seldom mentioned by name [in McFarlane’s diaries], as though he cannot bear to speak it aloud. He calls the books "the juveniles." At the time McFarlane was living in northern Ontario with a wife and infant children, attempting to make a living as a freelance fiction writer.

Nov. 12, 1932: "Not a nickel in the world and nothing in sight. Am simply desperate with anxiety. . . . What's to become of us this winter? I don't know. It looks black."

Jan. 23, 1933: "Worked at the juvenile book. The plot is so ridiculous that I am constantly held up trying to work a little logic into it. Even fairy tales should be logical."

Jan. 26, 1933: "Whacked away at the accursed book."

June 9, 1933: "Tried to get at the juvenile again today but the ghastly job appalls me."

Jan. 26, 1934: "Stratemeyer sent along the advance so I was able to pay part of the grocery bill and get a load of dry wood."

Finally: "Stratemeyer wants me to do another book. . . . I always said I would never do another of the cursed things but the offer always comes when we need cash. I said I would do it but asked for more than $85, a disgraceful price for 45,000 words."

He got no raise.

McFarlane eventually gritted his teeth and abandoned the series when he realized that the pressures of grinding out new installments had driven him to alcoholism. After shaking that addiction at a treatment center McFarlane never wrote another Hardy Boys book and instead went on to a relatively successful career as a novelist and screenwriter. But the ghosts of Frank and Joe continued to haunt him. Reportedly when McFarlane was near death in 1977 he would awaken from a diabetic coma screaming, having hallucinated that upon his death he would only be remembered for writing the Hardy Boys.

So, what's the take away here? Were we all just wrong as kids? And what about the fact that after reading the Hardy Boys, or the "sister" Nancy Drew series, most of us went on, and graduated to better books, doing so with an instilled love of reading, and of mysteries?

A funny thing about trying to re-live parts of one’s childhood. Through an adult’s eyes things just don’t look the same. Returning to our earliest literary loves can be as unpalatable as returning to Gerber's baby food. If you try this anyway (the literature, not the baby food), be prepared for some disappointment, or worse. But at the same time remember that what we saw, and did, as children, and what inspired and molded us, made us what we are today. No matter how bad those Hardy Boy books may be when viewed through adult eyes -- our own now, or that aghast librarian’s I encountered in 1956 -- Frank and Joe (and Nancy Drew) for many of us provided that initial flame, the catalyst that ignited a lifelong interest in mystery fiction.

So, well done, Franklin W. Dixon (and everyone behind his curtain). Poorly written, but still, in the end, well done!

So, well done, Franklin W. Dixon (and everyone behind his curtain). Poorly written, but still, in the end, well done!

Lawrence Block wrote an excellent article on procrastination in his book, Telling Lies For Fun And Profit. The book is a collection of the columns Mr. Block wrote for Writer's Digest. In the article he talks about Creative Procrastination, the time we sometimes spend doing things other than writing. Not always, but often that time is really when our subconscious works on our story. Yes, really. Of course, that's not always the case. Often writers just put off writing and doing other things. I've vacuumed floors, cleaned bathrooms, done laundry, taken a walk or a shower just to keep from sitting down and working on my WIP (work in progress.) But he isn't saying to become a sloth either. What you have isn't necessarily writer's block.

Lawrence Block wrote an excellent article on procrastination in his book, Telling Lies For Fun And Profit. The book is a collection of the columns Mr. Block wrote for Writer's Digest. In the article he talks about Creative Procrastination, the time we sometimes spend doing things other than writing. Not always, but often that time is really when our subconscious works on our story. Yes, really. Of course, that's not always the case. Often writers just put off writing and doing other things. I've vacuumed floors, cleaned bathrooms, done laundry, taken a walk or a shower just to keep from sitting down and working on my WIP (work in progress.) But he isn't saying to become a sloth either. What you have isn't necessarily writer's block.