Red Dawn was released 35 years ago this August. I think it's aged pretty well. The silly stuff is just as silly as it was back then, and the good parts still hold up.

If you don't know the premise, here it is: Russia invades the U.S. Proxy forces from Cuba and Nicaragua come boiling up the middle of the country, between the Rockies and the Mississippi, the Soviets reinforce across the Bering Strait and down into the Great Plains. Caught by surprise, small pockets of resistance spring up, and in a small Colorado town, a bunch of high school kids learn evasion and ambush techniques, and take the fight to the occupying troops. If it all sounds faintly ridiculous, it is.

The writer/director John Milius got raked over the coals for what was widely seen as a Red-baiting, loony Right fantasy, but in spite of the fact that Gen. Al Haig loved it, Red Dawn is deeper than it seems, at first blush. It's not really about Colorado teenagers at all. To me, it was obvious from the get-go that Milius was making a picture about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the kids were stand-ins for the mujahideen.

Aside from that, or in spite of it, or any and all of the above, I'm always drawn in by the sheer exhilaration of the movie-making. Once you swallow the set-up, the rest of it is inevitable, fated and austere. It's beautifully shot, by Ric Waite, the New Mexico locations framed in wide ratio. The score, Basil Poledouris. The rigorous structure, and the kinetic pacing, but at the same time a sense of natural rhythms, the movement of the seasons, the shape of silence. For an action picture, it's got its fair share of stillness and melancholy.

And for all that it's about the kids, it's actually the grown-ups who put it in sharper relief. Powers Boothe, the American pilot who bails out over occupied territory. "Shoot straight for once, you Army pukes," has got to be one of the great exit lines. Bill Smith, the Spetsnaz colonel brought in to exterminate the Wolverines. "You need a hunter. I am a hunter." (Bill Smith speaking his own Russian, a bonus.) Ron O'Neal, the Cuban revolutionary who loses his faith. "I can't remember what it was to be warm. It seems a thousand years since I was a small boy in the sun."

Corny? You bet. Affecting? Absolutely.

Red Dawn wears its heart on its sleeve. Its innocence, or lack of guile, is suspect, even embarrassing. But it has an unnervingly specific authenticity. It respects the conventions, and yet - I can't quite put my finger on it. The picture is subversive. It's not about glory, that's for damn sure. It's about loss, although it might be about redemption, too, but it doesn't promise us much comfort.

*

Some years later, I wrote a spy story called The Bone Harvest, set in the early onset of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. I have to wonder, the way we do, how much was I influenced by Red Dawn? Which might seem like a dumb question, but let's be honest, we pick up all kinds of stuff, attracted by its texture or reflection, like beach glass or bottle caps. Hemingway once said no decent writer ever copies, we steal.

If in fact I took something away from Red Dawn for my own book, I hope it was a certain naive muscularity, the notion that you can will something to happen. I don't mean this in the meta-sense of getting a book written, I mean that the story I wanted to tell was how raw determination could put boots on the ground. Stubbornness a virtue, not playing well with others. If that's the lesson, it's not just the story arc of Red Dawn, it pretty much defines John Milius' career, but you could have a worse role model.

Showing posts with label alternative history. Show all posts

Showing posts with label alternative history. Show all posts

28 August 2019

Red Dawn

Labels:

alternative history,

Cold War,

David Edgerley Gates,

wars

05 October 2016

The Way It Wasn't

A month ago I noticed that my wife was reading The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. What made that particularly interesting was that I was reading Underground Airlines by Ben H. Winters.

Both of them fall into the genre of Alternative History (AH), which is usually considered part of science fiction. Science fiction, more than most forms of fiction, is all about "What if?" and AH asks "What if events didn't turn out as they did?"

The oldest example of AH we know of is about 2100 years old. The Roman author Livy pondered the question: What if Alexander the Great had gone west (toward the still developing city of Rome) instead of east?

Let's jump ahead past a few medieval examples and land in 1931 when John Squires published If It Had Happened Otherwise, a collection of essays by different authors, speculating on how various turning points of history could have turned out differently. One of them, "If Lee Had Not Won At Gettysburg," is a double twist (as you can probably tell), being written from the point of view of a historian in a world in which the South did win the Civil War. He tries to speculate how things would have turned out if the North had conquered.

You may have heard of the author of that clever essay. He later won the Nobel Prize for Literature, but Winston Churchill was better known for other accomplishments.

You may be surprised that an Englishman like Churchill should have chosen the American Civil War as his subject but that event seems to have an obsessive interest for alternative historians. Remember those books my wife and I were reading? Even The New Yorker recently took note of our country's obsession with the Underground Railroad.

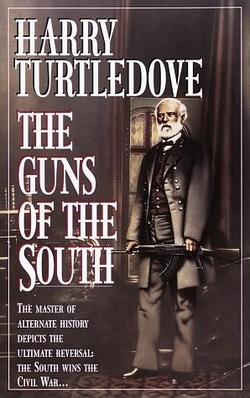

My favorite AH writer is Harry Turtledove and he was inspired to get a PhD in Byzantine History by an AH novel by L. Sprague De Camp called Lest Darkness Fall. Turtledove's masterpiece is The Guns of the South (Yup, that War Between the States again). It starts with a real event: Robert E. Lee writing to Jefferson Davis in 1864 to say the Confederacy could not win. Except in Turtledove's book the letter is interrupted by some strangers with funny accents who want to sell the South some new weapons called AK-47s. You see, some Afrikaaners got their hands on a time machine and decided to nip Black aspirations in the bud by saving slavery.

You can argue that that is not pure alternative history since it involves a science fiction concept like time travel. In that case you might prefer another Turtledove novel - and it's a mystery! - The Two Georges, co-written with, of all people, the actor Richard Dreyfuss. The heroes are cops in the 1960s, but in this world King George III never went mad and when his colonies started protesting his policies he invited the leaders to England to discuss it. The result is that George Washington became the first Governor-General of British North America.

Some of you may have seen the recent TV series, The Man in the High Castle, which is based (loosely, I hear) on a classic AH novel by Philip K. Dick. It explores a world in which the Axis beat the Allies.

To my mind, there are two essential elements to an AH fiction: How did things turn out this way (as opposed to the way we know they did)? And what would happen if they had? At its best, AH becomes a thought experiment: If Nixon beat Kennedy, how would the sixties have changed? What if the Spanish Armada had won?

I have had three fantasy stories published and while none of them are pure AH they all, shall we say, partake of its nature.

I have had three fantasy stories published and while none of them are pure AH they all, shall we say, partake of its nature.

After George W. Bush became president, Edward J. McFadden III and E. Sedia proposed Jigsaw Nation, a book of stories that asked: What if the blue states seceded from the nation? My story, "Down in the Corridor," takes place in the narrow strip of land between Mexico and the Pacific States of America, connecting the USA with the Pacific. Yes, it's a crime story, but it's not true AH because it was imaging an alternative near future, not a past. (Recently Andrew MacRae came up with a similar idea for an anthology about post-current events.)

"Letters to the Journal of Experimental History" appeared in a short-lived humor webzine called The Town Drunk. It's based on the multi-verse theory of time travel; that is, if you go back in time and, say, kill Hitler, it doesn't change our universe, it merely kickstarts a new one. You can read it here.

"Letters to the Journal of Experimental History" appeared in a short-lived humor webzine called The Town Drunk. It's based on the multi-verse theory of time travel; that is, if you go back in time and, say, kill Hitler, it doesn't change our universe, it merely kickstarts a new one. You can read it here.

And then there is "Street of the Dead House," which appeared in nEvermore! (and has been reprinted in Best American Mystery Stories 2016 and Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror 2016, he said modestly.) This one is Alternative Literature, reinterpreting (without changing) a classic Edgar Allan Poe story.

Anyone out there like this genre? If so, tell me your favorites.

Both of them fall into the genre of Alternative History (AH), which is usually considered part of science fiction. Science fiction, more than most forms of fiction, is all about "What if?" and AH asks "What if events didn't turn out as they did?"

The oldest example of AH we know of is about 2100 years old. The Roman author Livy pondered the question: What if Alexander the Great had gone west (toward the still developing city of Rome) instead of east?

Let's jump ahead past a few medieval examples and land in 1931 when John Squires published If It Had Happened Otherwise, a collection of essays by different authors, speculating on how various turning points of history could have turned out differently. One of them, "If Lee Had Not Won At Gettysburg," is a double twist (as you can probably tell), being written from the point of view of a historian in a world in which the South did win the Civil War. He tries to speculate how things would have turned out if the North had conquered.

You may have heard of the author of that clever essay. He later won the Nobel Prize for Literature, but Winston Churchill was better known for other accomplishments.

You may be surprised that an Englishman like Churchill should have chosen the American Civil War as his subject but that event seems to have an obsessive interest for alternative historians. Remember those books my wife and I were reading? Even The New Yorker recently took note of our country's obsession with the Underground Railroad.

My favorite AH writer is Harry Turtledove and he was inspired to get a PhD in Byzantine History by an AH novel by L. Sprague De Camp called Lest Darkness Fall. Turtledove's masterpiece is The Guns of the South (Yup, that War Between the States again). It starts with a real event: Robert E. Lee writing to Jefferson Davis in 1864 to say the Confederacy could not win. Except in Turtledove's book the letter is interrupted by some strangers with funny accents who want to sell the South some new weapons called AK-47s. You see, some Afrikaaners got their hands on a time machine and decided to nip Black aspirations in the bud by saving slavery.

You can argue that that is not pure alternative history since it involves a science fiction concept like time travel. In that case you might prefer another Turtledove novel - and it's a mystery! - The Two Georges, co-written with, of all people, the actor Richard Dreyfuss. The heroes are cops in the 1960s, but in this world King George III never went mad and when his colonies started protesting his policies he invited the leaders to England to discuss it. The result is that George Washington became the first Governor-General of British North America.

Some of you may have seen the recent TV series, The Man in the High Castle, which is based (loosely, I hear) on a classic AH novel by Philip K. Dick. It explores a world in which the Axis beat the Allies.

To my mind, there are two essential elements to an AH fiction: How did things turn out this way (as opposed to the way we know they did)? And what would happen if they had? At its best, AH becomes a thought experiment: If Nixon beat Kennedy, how would the sixties have changed? What if the Spanish Armada had won?

After George W. Bush became president, Edward J. McFadden III and E. Sedia proposed Jigsaw Nation, a book of stories that asked: What if the blue states seceded from the nation? My story, "Down in the Corridor," takes place in the narrow strip of land between Mexico and the Pacific States of America, connecting the USA with the Pacific. Yes, it's a crime story, but it's not true AH because it was imaging an alternative near future, not a past. (Recently Andrew MacRae came up with a similar idea for an anthology about post-current events.)

And then there is "Street of the Dead House," which appeared in nEvermore! (and has been reprinted in Best American Mystery Stories 2016 and Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror 2016, he said modestly.) This one is Alternative Literature, reinterpreting (without changing) a classic Edgar Allan Poe story.

Anyone out there like this genre? If so, tell me your favorites.

Labels:

alternative history,

Livy,

Lopresti,

science fiction,

Winston Churchill

14 August 2013

Fatherlands

by David Edgerley Gates

We were just walking out of CASABLANCA, the new picture starring Ronald Reagan and Ann Sheridan....

I always thought this would be a cool opening line for a story, setting up the alternate history angle from the get-go. (There are plenty of these might-have-beens. The original casting Peckinpah wanted for THE WILD BUNCH, for example, was Lee Marvin and Brian Keith.) In the case of CASABLANCA, though, this was a misleading Warners PR plant: Bogart always had a lock on the part.

Alternate history is an interesting genre, usually lying somewhere on the outskirts of SF or even fantasy. The first one I remember reading was packaged in an Ace double novel, and I've forgotten the title, to my chagrin, but the premise was that the Spanish Armada had successfully invaded England, so Spain became the dominant European and New World power for the next four centuries. Often the key to alternate history is just such a defining event. If typhus hadn't ravaged Hannibal's armies in Italy, Rome would have remained a provincial backwater, and Carthage taken control of the Mediterranean trade routes.

What if the Germans had won WWII? This being an enduring subset of the genre, and a fascinating one. Len Deighton's SS-GB takes place in an occupied Great Britain, after the RAF loses the air war. Robert Harris hit the ground running with FATHERLAND, an enormously spooky thriller, hinging on the plausibility that all evidence of the Holocaust could be destroyed, and the memory of mass murder erased from the historical record. The precursor of both these books is Philip K. Dick's THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE.

Japan occupies the West Coast, to the Rockies, Germany the East Coast, to the Mississippi. A weak buffer state exists between them. The engine of the story is the struggle of the two great Axis powers against each other, worldwide, a Cold War that's about blow wide open, and there are also factions and succession rivalries, inside the Reich. The conspiracies, though, are the backdrop to more intimate and familiar characters, and the mechanisms they develop for living in a police state---the Japanese hegemony is nowhere near as brutal, on a daily basis, as the German.

Three dramatic devices surface and resurface all through the book. The first is historicity, the quality an object or an artifact has to absorb and embody the past, a Zippo lighter Franklin Roosevelt may have had in his pocket, say, when he was assassinated in 1932. The play between the counterfeit and the authentic mirrors the storyline. Are we imagining all this? (And there's a huge black market in fakes, such as Zippo lighters.) The second meta-device is a novel within the novel, an alternate history, in which the Allies turn out to have won the war. But this fiction isn't quite the world as we now know it, either. It's skewed in other, odd ways, so again, 'reality,' or authenticity, is slippery, a construct, really, and not immutable. This idea is doubled on itself with the third device, which I think is utterly inspired. Every character in the book consults the I CHING, and the fall of the yarrow stalks or the coins establishes fate. In fact (or, in 'fact'), the novel within the novel is written using the I CHING, each fictional historical development a roll of the dice, in effect. Or to put it another way, pay every attention to the man behind the curtain.

None of this is meant to suggest THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE is self-indulgent, or some elaborate post-modernist prank. It's mischievous, and often deceptive, but always highly entertaining, and entertains the unexpected. Nobody in the story is flat, or arbitrary. Everybody holds their own as a fully-fleshed person, and each of them holds their own future in trust, however the yarrow stalks may fall. The great strength of the book is probably that character is fate, and nothing is fated. There will always be defining events, but history is accident. The choices we make are only inevitable in hindsight. For there to be an alternate reality, we have to decide first which fiction we believe.

We were just walking out of CASABLANCA, the new picture starring Ronald Reagan and Ann Sheridan....

I always thought this would be a cool opening line for a story, setting up the alternate history angle from the get-go. (There are plenty of these might-have-beens. The original casting Peckinpah wanted for THE WILD BUNCH, for example, was Lee Marvin and Brian Keith.) In the case of CASABLANCA, though, this was a misleading Warners PR plant: Bogart always had a lock on the part.

Alternate history is an interesting genre, usually lying somewhere on the outskirts of SF or even fantasy. The first one I remember reading was packaged in an Ace double novel, and I've forgotten the title, to my chagrin, but the premise was that the Spanish Armada had successfully invaded England, so Spain became the dominant European and New World power for the next four centuries. Often the key to alternate history is just such a defining event. If typhus hadn't ravaged Hannibal's armies in Italy, Rome would have remained a provincial backwater, and Carthage taken control of the Mediterranean trade routes.

What if the Germans had won WWII? This being an enduring subset of the genre, and a fascinating one. Len Deighton's SS-GB takes place in an occupied Great Britain, after the RAF loses the air war. Robert Harris hit the ground running with FATHERLAND, an enormously spooky thriller, hinging on the plausibility that all evidence of the Holocaust could be destroyed, and the memory of mass murder erased from the historical record. The precursor of both these books is Philip K. Dick's THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE.

Japan occupies the West Coast, to the Rockies, Germany the East Coast, to the Mississippi. A weak buffer state exists between them. The engine of the story is the struggle of the two great Axis powers against each other, worldwide, a Cold War that's about blow wide open, and there are also factions and succession rivalries, inside the Reich. The conspiracies, though, are the backdrop to more intimate and familiar characters, and the mechanisms they develop for living in a police state---the Japanese hegemony is nowhere near as brutal, on a daily basis, as the German.

Three dramatic devices surface and resurface all through the book. The first is historicity, the quality an object or an artifact has to absorb and embody the past, a Zippo lighter Franklin Roosevelt may have had in his pocket, say, when he was assassinated in 1932. The play between the counterfeit and the authentic mirrors the storyline. Are we imagining all this? (And there's a huge black market in fakes, such as Zippo lighters.) The second meta-device is a novel within the novel, an alternate history, in which the Allies turn out to have won the war. But this fiction isn't quite the world as we now know it, either. It's skewed in other, odd ways, so again, 'reality,' or authenticity, is slippery, a construct, really, and not immutable. This idea is doubled on itself with the third device, which I think is utterly inspired. Every character in the book consults the I CHING, and the fall of the yarrow stalks or the coins establishes fate. In fact (or, in 'fact'), the novel within the novel is written using the I CHING, each fictional historical development a roll of the dice, in effect. Or to put it another way, pay every attention to the man behind the curtain.

None of this is meant to suggest THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE is self-indulgent, or some elaborate post-modernist prank. It's mischievous, and often deceptive, but always highly entertaining, and entertains the unexpected. Nobody in the story is flat, or arbitrary. Everybody holds their own as a fully-fleshed person, and each of them holds their own future in trust, however the yarrow stalks may fall. The great strength of the book is probably that character is fate, and nothing is fated. There will always be defining events, but history is accident. The choices we make are only inevitable in hindsight. For there to be an alternate reality, we have to decide first which fiction we believe.

Location:

Santa Fe, NM, USA

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)