droll, wait until you read this week’s clunker.

I admire O Henry’s stories, I really do, but his heavy drinking shows, drinking that led to an early death by liver failure. But that’s just my opinion. These turkeys managed to get published posthumously.

The ‘O’ in William Sydney Porter’s O Henry pseudonym originally stood for Olivier. He used that pen name only once and changed it to simply ‘O’ to disguise the fact he was writing while in federal prison for bank embezzlement. A friend forwarded manuscripts to publishers to further obscure Porter’s whereabouts.

Without doubt, he loved his wife, Athol. Porter married her knowing she suffered from consumption, the disease tuberculosis that would eventually take her life.

Athol encouraged her husband to write, which he began while working in Austin and Houston. After a boy who died in childbirth, Athol bore a daughter, Margaret.

After Porter’s indictment for bank fraud, he fled the country, arriving in Trujillo, Honduras. Porter planned for his wife and daughter to join him, but upon learning she was dying of tuberculosis, Porter returned and gave himself up. While serving three years of a five-year sentence in an Ohio federal prison, he wrote short stories to help support his young daughter, Margaret.

After prison, Porter moved to New York where he commenced his literary career in earnest. These Shamrock Jolnes stories were written shortly before his 1910 death at age 47.

The Sleuths

by O Henry

(© 1911)

In the Big City a man will disappear with the suddenness and completeness of the flame of a candle that is blown out. All the agencies of inquisition – the hounds of the trail, the sleuths of the city’s labyrinths, the closet detectives of theory and induction – will be invoked to the search. Most often the man’s face will be seen no more. Sometimes he will re-appear in Sheboygan or in the wilds of Terre Haute, calling himself one of the synonyms of ‘Smith’, and without memory of events up to a certain time, including his grocer’s bill. Sometimes it will be found, after dragging the rivers, and polling the restaurants to see if he may be waitng for a well-done sirloin, that he has moved next door.

This snuffing out of a human being like the erasure of a chalk man from a blackboard is one of the most impressive themes in dramaturgy

The case of Mary Snyder, in point, should not be without interest.

A man of middle age, of the name of Meeks, came from the West to New York to find his sister, Mrs. Mary Snyder, a widow, aged fifty-two who had been living for a year in a tenement house in a crowded neighborhood.

At her address he was told that Mary Snyder had moved away longer than a month before. No one could tell him the new address.

On coming out Mr. Meeks addressed a policeman who was standing on the corner, and explained his dilemma.

“My sister is very poor,” he said, “and I am anxious to find her. I have recently made quite a lot of money in a lead mine, and I want her to share my prosperity. There is no use in advertising her, because she cannot read.”

The policeman pulled his mustache and looked so thoughtful and mighty that Meeks could almost feel the joyful tears of his sister Mary drooping upon his bright blue tie.

“You go down in the Canal Street neighborhood,” said the policeman, “and get a job drivin’ the biggest dray you can find. There’s old women always getting’ knocked over by drays down there. You might see ‘er among ‘em. If you don’t want to do that you better go ‘round to headquarters and get ‘em to put a fly cop onto the dame.”

At police headquarters, Meeks received ready assistance. A general alarm was sent out and copies of a photograph of Mary Snyder that her brother had were distributed among the stations. In Mulberry Street the chief assigned Detective Mullins to the case.

The detective took Meeks aside and said:

“This is not a very difficult case to unravel. Shave off your whiskers, fill your pockets with good cigars, and meet me in the café of the Waldorf at three o’clock this afternoon.”

Meeks obeyed. He found Mullins there. They had a bottle of wine, while the detective asked questions concerning the missing woman.

“Now,” said Mullins, “New York is a big city, but we’ve got the detective business systematized. There are two ways we can go about finding your sister. We will try one of ‘em first. You say she’s fifty-two?”

“A little past,” said Meeks.

The detective conducted the Westerner to a branch advertising office of one of the largest dailies. There he wrote the following “ad” and submitted it to Meeks.

“Wanted, at once – one hundred attractive chorus girls for a new musical comedy. Apply all day at No.–- Broadway.”

Meeks was indignant.

“My sister,” said he, “is a poor, hard-working, elderly woman. I do not see what aid an advertisement of this kind would be toward finding her.”

“All right,” said the detective. “I guess you don’t know New York. But if you’ve got a grouch against this scheme we’ll try the other one. It’s a sure thing. But it’ll cost you more.”

“Never mind the expense,” said Meeks; “we’ll try it.”

The sleuth led him back to the Waldorf. “Engage a couple of bedrooms and a parlor,” he advised, “and let’s go up.”

This was done, and the two were shown to a superb suite on the fourth floor. Meeks looked puzzled. The detective sank into a velvet armchair, and pulled out his cigar case.

“I forgot to suggest, old man,” he said, “that you should have taken the rooms by the month. They wouldn’t have stuck you so much for em.”

“By the month!” exclaimed Meeks. “What do you mean?”

“Oh, it’ll take time to work the game this way. I told you it would cost you more. We’ll have to wait till spring. There’ll be a new city directory out then. Very likely your sister’s name and address will be in it.”

Meeks rid himself of the city detective at once. On the next day some one advised him to consult Shamrock Jolnes, New York’s famous private detective, who demanded fabulous fees, but performed miracles in the way of solving mysteries and crimes.

After waiting for two hours in the anteroom of the great detective’s apartment, Meeks was shown into his presence. Jolnes sat in a purple dressing gown at an inlaid ivory chess table, with a magazine before him, trying to solve the mystery of “They.” The famous sleuth’s thin, intellectual face, piercing eyes, and rate per word are too well known to need description.

Meeks set forth his errand. “My fee, if successful, will be $500,” said Shamrock Jolnes.

Meeks bowed his agreement to the price.

“I will undertake your case, Mr. Meeks,” said Jones, finally. “The disappearance of people in this city has always been an interesting problem to me. I remember a case that I brought to a successful outcome a year ago. A family bearing the name of Clark disappeared suddenly from a small flat in which they were living I watched the flat building for two months for a clue. One day it struck me that a certain milkman and a grocer’s boy always walked backward when they carried their wares upstairs. Following out by induction the idea that this observation gave me, I at once located the missing family. They had moved into the flat across the hall and changed their name to Kralc.”

Shamrock Jolnes and his client went to the tenement house where Mary Snyder had lived, and the detective demanded to be shown the room in which she had lived. It had been occupied by no tenant since her disappearance.

The room was small, dingy, and poorly furnished. Meeks seated himself dejectedly on a broken chair, while the great detective searched the walls and floors and the few sticks of old, rickety furniture for a clue.

At the end of half an hour Jolnes had collected a few seemingly umintelligible articles – a cheap black hatpin, a piece torn off a theatre programme, and the end of a small torn card on which was the word “Left” and the characters “C 12.”

Shamrock Jolnes leaned against the mantel for ten minutes, with his head resting upon his hand, and an absorbed look upon his intellectual face. At the end of that time he exclaimed, with animation:

“Come, Mr. Meeks; the problem is solved. I can take you directly to the house where your sister is living. And you may have no fears concerning her welfare, for she is amply provided with funds – for the present at least.”

Meeks felt joy and wonder in equal proportions.

“How did you manage it?” he asked, with admiration in his tones.

Perhaps Jolnes’s only weakness was a professional pride in his wonderful achievements in induction. He was ever ready to astound and charm his listeners by describing his methods.

“By elimination,” said Jolnes, spreading his clues upon a little table, “I got rid of certain parts of the city to which Mrs. Snyder might have removed. You see this hatpin? That eliminates Brooklyn. No woman attempts to board a car at the Brooklyn Bridge without being sure that she carries a hatpin with which to fight her way into a seat. And now I will demonstrate to you that she could not have gone to Harlem. Behind this door are two hooks in the wall. Upon one of these Mrs. Snyder has hung her bonnet, and upon the other her shawl. You will observe that the bottom the hanging shawl has gradually made a soiled streak against the plastered wall. The mark is clean-out, proving that there is no fringe on the shawl. Now, was there ever a case where a middle-aged woman, wearing a shawl, boarded a Harlem train without there being a fringe on the shawl to catch in the gate and delay the passengers behind her? So we eliminate Harlem.

“Therefore I conclude that Mrs. Snyder has not moved very far away. On this torn piece of card you see the word ‘Left, the letter ‘C,’ and the number ‘12.’ Now, I happen to know that No. 12 Avenue C is a first-class boarding house, far beyond your sister’s means – as we suppose. But then I find this piece of a theatre programme, crumpled into an odd shape. What meaning does it convey? None to you, very likely, Mr. Meeks; but it is eloquent to one whose habits and training take cognizance of the smallest things.

“You have told me that your sister was a scrub woman. She scrubbed the floors of offices and hallways. Let us assume that she procured such work to perform in a theatre. Where is valuable jewellery lost the oftenest, Mr. Meeks? In the theatres, of course. Look at that piece of programme, Mr. Meeks. Observe the round impression in it. It has been wrapped around a ring – perhaps a ring of great value. Mrs. Snyder found the ring while at work in the theatre. She hastily tore off a piece of a programme, wrapped the ring carefully, and thrust it into her bosom. The next day she disposed of it, and with her increased means, looked about her for a more comfortable place in which to live. When I reach thus far in the chain I see nothing impossible about No. 12 Avenue C. It is there we will find your sister, Mr. Meeks.”

Shamrock Jolnes concluded his convincing speech with the smile of a successful artist. Meeks’s admiration was too great for words. Together they went to No. 12 Avenue C. It was an old-fashioned brownstone house in a prosperous and respectable neighborhood.

They rang the bell, and on inquiry were told that no Mrs. Snyder was known there, and that not within six months had a new occupant come to the house.

When they reached the sidewalk again, Meeks examined the clues which he had brought away from his sister’s old room.

“I am no detective,” he remarked to Jolnes as he raised the piece of theatre programme to his nose, “but it seems to me that instead of a ring having been wrapped in this paper it was one of those round peppermint drops. And this piece with the address on it looks to me like the end of a seat coupon – No. 12, row C, left aisle.”

Shamrock Jolnes had a far-away look in his eyes.

“I think you would do well to consult Juggins,” said he.

“Who is Juggins?” asked Meeks.

“He is the leader,” said Jolnes, “of a new modern school of detectives. Their methods are different from ours, but it is said that Juggins has solved some extremely puzzling cases. I will take you to him.”

They found the greater Juggins in his office. He was a small man with light hair, deeply absorbed in reading one of the bourgeois works of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The two great detectives of different schools shook hands with ceremony, and Meeks was introduced.

“State the facts,” said Juggins, going on with his reading.

When Meeks ceased, the greater one closed his book and said:

“Do I understand that your sister is fifty-two years of age, with a large mole on the side of her nose, and that she is a very poor widow, making a scanty living by scrubbing, and with a very homely face and figure?”

“That describes her exactly,” admitted Meeks. Juggins rose and put on his hat.

“In fifteen minutes,” he said, “I will return, bringing you her present address.”

Shamrock Jolnes turned pale, but forced a smile.

Within the specified time Juggins returned and consulted a little slip of paper held in his hand.

“Your sister, Mary Snyder,” he announced calmly, “will be found at No. 162 Chilton Street. She is living in the back hall bedroom, five flights up. The house is only four blocks from here,” he continued addressing Meeks. Suppose you go and verify the statement and then return here. Mr Jolnes will await you, I dare say.”

Meeks hurried away. In twenty minutes he was back again, with a beaming face.

“She is there and well!” he cried. “Name your fee!”

“Two dollars,” said Juggins.

When Meeks had settled his bill and departed, Shamrock Jolnes stood with his hat in his hand before Juggins.

“If it would not be asking too much,” he stammered , “if you would favor me so far – would you object to ––”

“Certainly not,” said Juggins, pleasantly. “I will tell you how I did it. You remember the description of Mrs. Snyder? Did you ever know a woman like that who wasn’t paying weekly instalments on an enlarged crayon portrait of herself? The biggest factory of that kind in the country is just around the corner. I went there and got her address off the books. That’s all.”

, a popular movie and western television series. The name, although not the plot, was taken from a short story by… O Henry.

1. Maybe I've been here before. Five

years ago in this space (wow, we've been doing this a long time,

haven't we?) I wrote a piece about incidental music in movies and TV,

(and by incidental I mean it wasn't written for that show and is

not being performed by a character). The inspiration was Leonard

Cohen's "Hallelujah" showing up in yet another TV show. I wrote: "It

was about five years ago that I concluded that the FCC had passed a new

rule requiring every TV show to feature 'Hallelujah.'" I now have

evidence that I was right (not about the FCC, but about the frequency

of that song's appearances.)

1. Maybe I've been here before. Five

years ago in this space (wow, we've been doing this a long time,

haven't we?) I wrote a piece about incidental music in movies and TV,

(and by incidental I mean it wasn't written for that show and is

not being performed by a character). The inspiration was Leonard

Cohen's "Hallelujah" showing up in yet another TV show. I wrote: "It

was about five years ago that I concluded that the FCC had passed a new

rule requiring every TV show to feature 'Hallelujah.'" I now have

evidence that I was right (not about the FCC, but about the frequency

of that song's appearances.)

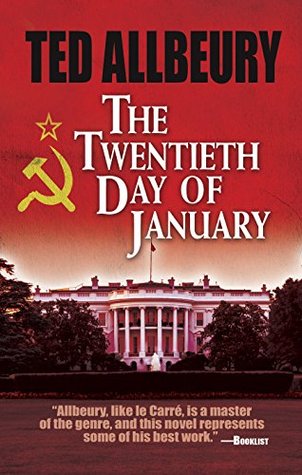

5. Riding a trend? But maybe the most interesting thing in the Strand (and my apologies to John Floyd and the other authors of fiction who appear therein) is a full-page ad for Ted Allbeury's novel The Twentieth Day of January. There

are plenty of ads in the magazine for books, but this one is almost

forty years old. So why bring it back now? Perhaps the plot

description holds a clue:

5. Riding a trend? But maybe the most interesting thing in the Strand (and my apologies to John Floyd and the other authors of fiction who appear therein) is a full-page ad for Ted Allbeury's novel The Twentieth Day of January. There

are plenty of ads in the magazine for books, but this one is almost

forty years old. So why bring it back now? Perhaps the plot

description holds a clue:  "Seemingly out of nowhere, wealthy businessman Logan Powell has become President-elect. But veteran intelligence agent James MacKay uncovers shocking evidence that suggest something might be terribly wrong with the election: is Powell actually a puppet of the Soviet Union?"

"Seemingly out of nowhere, wealthy businessman Logan Powell has become President-elect. But veteran intelligence agent James MacKay uncovers shocking evidence that suggest something might be terribly wrong with the election: is Powell actually a puppet of the Soviet Union?"