Last week, my short story "The Bridesmaid's Tale" appeared in Black Cat Weekly, and I shared the news with all three of my friends. Later that same day, one of them congratulated me on how well I captured the thought process of the female lead/narrator. I thanked him, but I'm not sure I really did it that well.

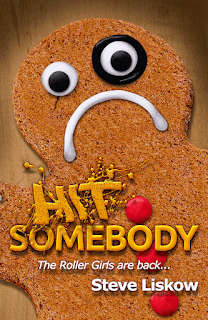

His comment made me curious enough to go back and look at all my published work, though, which took about five minutes. Most of my novels use multiple-third point of view, and the majority of those characters are male. There are exceptions, of course: both Roller Derby novels have several scenes in the POV of various skaters, and Megan Traine and Beth Shepard get screen time in the novels with their partners. Words of Love has three female POV characters, more than any other book, but if you read it, you'll see why.

Strong female characters abound in my short stories, whether they're the POV character or not. I grew up in a family of strong intelligent women, and during my theater years, I usually worked with a female stage manager and often a female producer. My favorite lights designer was a woman who began as a stage manager and became a good director, too. She also wrote at least one good play that I remember.

Women are more interesting because the still prevalent glass ceiling forces them to be more resourceful and flexible to succeed in various professions. They also need more sense of humor to cope with the crap. Many of my characters take a hard look at themselves and understand how they have to change to solve the current problem. Medically, we know women have a higher threshold of pain and a higher resistance to disease (Otherwise, the race would have died out long ago), and they may have a higher IQ.

I've sold sixteen short stories with a female narrator (four not yet published), and many others have a woman who drives the action even if she doesn't tell the story. Women narrate five of the ten stories currently floating in Submission Limbo, too.

It's easier to masquerade as a woman in a short story because the length gives you less room to make a mistake. I try to convey an attitude through dialogue and thought process, and sometimes using kinesthetic perceptions makes that easier. That's psych and teacher jargon, so let me mansplain here.

We process information through one of three primary modes. About 80% of the population is visual, so they watch and look and read to gain their information. Another 10-12% are auditory and listen well. These people remember a lecture or can follow instructions easily (Many of them become teachers). The remaining few are kinesthetic, who learn from doing, a combination of muscle memory and experience. These are the kids who take the game or toy apart on Christmas morning without reading the instructions and figure out how it works by trial and error. Many of them can call up the emotions they felt during an experience long after it happened. These people are often dancers, athletes, or actors.

Most of my women characters are empaths and have a kinesthetic streak. They're aware of their bodies and feel emotions and slights deeply.

Angie, narrator of "The Bridesmaid's Tale," knows that her older sister Bethesda (the Bride) is taller and curvier than she is, AND is Daddy's favorite. Angie accepts that she'll look terrible in the bridesmaids' gowns Bethesda selected for her taller, bustier friends, and takes the hit for the team. Unlike Bethesda, though, Angie doesn't live off the family fortune. She's in med school at Tufts, studying to become a veterinarian, and her academic strengths help drive the plot.

So does her attitude. She and Bethesda have been at each other's throats since they were old enough to walk, but blood still trumps everything else. Angie won't let her sister be put in danger. She's resourceful, devious, and funny. She tells us she was in her teens before she learned her sister (Whom she refers to as "Bitch-G," for "Bitch-Goddess") was named after their mother's city of birth. Before that, she checked the family medicine cabinet to see if she was named after a pill. She learned that "Bitch" was a handy word in a girl's vocabulary when she saw Mom's reaction to it the first time she said it.

My list says nine stories have been sold that will probably appear by the end of 2023, three of them by June of this year. A woman drives the plot in five of them, solving the mystery, doing bad stuff, or sometimes narrating.

Using a person like yourself as the protagonist (or narrator) runs the risk of taking values and ideas for granted and omitting them from the story. Barnes and Guthrie have elements of me, but not many. Featuring women forces me to pay attention. For what it's worth, readers know more about the families (we've met both of them) and backstory of Beth Sehpard, Tori MacDonald and Megan Traine than they do about Zach Barnes, Trash Hendrix, or Woody Guthrie.

P.S. My wife (wearing the green jacket in the photo) closed Saturday night in The Trouble with Space Cannibals, a weird and wacky play, sort of Star Trek meets The Office. The male playwrights made all the officer on the starship LeVAR BurTONNE female and mentioned the glass ceiling that holds men down. My wife played Science Officer Wendy Mansplain…