Last Monday, Jan Grape wrote about the Meet My Character Blog Tour. Tagged authors write about their main characters by answering questions on their blogs. The writers then invite one to five other authors to join. Jan tagged me, so here goes:

1. What is the name of your character? Is he or she fictional or a historic person?

The main character of my first six books is fictional Callie Parrish. Her full name is Calamine Lotion Parrish. When her mother died giving birth to their sixth child, Callie's father got drunk--really drunk. This was his first daughter and the only thing female he could think of was the color pink. The only pink that came to mind was Calamine Lotion. Callie frequently thanks heaven that Pa didn't think of Pepto Bismol. If you don't recognize the particular shade of pink in front of me in the above picture, it's a Victoria's Secret pink bag which contained a gift from Jane.

2. When and where is the story set?

Callie's adventures are set in contemporary times and primarily in the fictional town of St. Mary located near coastal Beaufort, SC. In the series, Callie and her BFF, visually handicapped Jane Baker, have encountered murders in other places such as a bluegrass festival on Surcie Island and a casket manufacturer in North Carolina.

4. What should we know about him/her?

Callie works as a cosmetician/Girl Friday at Middleton's Mortuary for her twin bosses, Otis and Odell Middleton. After graduating from St. Mary High School, she left St. Mary to attend the university in Columbia, SC, where she married and worked for several years as a kindergarten teacher. After her husband "did what he did" to make her divorce him, she returned to St. Mary where she spends time with Jane, her daddy, her five brothers, and whoever she's dating. She likes working at the funeral home better than teaching kindergarten because the people she works with at Middleton's lie still instead of jumping around all the time, don't yell or cry, and don't have to tee-tee every five minutes.

Callie's time teaching five-year-olds led her to stop using some of the language she grew up with living in a house with only her father and five older brothers. Instead, she "kindergarten cusses," which consists of "Dalmation!" when she's irritated and "Shih tzu!" when she's extremely annoyed. She has a Harlequin Great Dane dog who's named Big Boy though he acts more like a girl dog. Callie is a talented banjo player and vocalist, but she's not perfect. She can't cook, and she's flat-chested which led her to wear inflatable bras because she's scared of breast-augmentation surgery.

5. What is the personal goal of this character?

In the first books, Callie's goals (besides solving murders and her own personal survival as well as Jane's) were to convince Jane to stop shoplifting and to comfort families by providing peaceful memory pictures of their deceased relatives. She also wanted a closer relationship with her redneck father and to meet a romantic interest as unlike her ex-husband as possible. She achieved these goals except finding the right romantic interest, but she's still looking.

6. Can we read about this character yet?

The six Callie Parrish mysteries are all available electronically. The first three are out-of-print, but used copies can sometimes be found on Amazon. Callie books four through six are available in print and electronically from Bella Rosa Books and on Amazon.

7. Who do you tag?

I've tagged Janice Law, and her Character Blog will appear right here on Monday, September 22, 2014. A surprise Character Blog is scheduled for my first Monday in November. If you're interested in participating in the Meet Your Character Blog Tour, let me know.

Until we meet again, take care of . . . you.

Showing posts with label Janice Law. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Janice Law. Show all posts

08 September 2014

Introducing Callie Parrish

by Fran Rizer

Labels:

books,

Fran Rizer,

Jan Grape,

Janice Law,

publishing

Location:

Columbia, SC, USA

28 July 2014

Moon Over Tangier

by Fran Rizer

Thanks to Janice Law and Leigh Lundin, I spent Friday suffering from self-induced sleep deprivation. When Leigh asked if anyone would like to review Janice Law’s newest novel, I volunteered. It arrived Thursday afternoon, and I didn’t stop reading until I completed it Friday morning. The official release date is the end of August, but I can’t wait to tell you about it. Here’s my review:

Until we meet again, take care of … you (and read this great new book by Janice!)

Moon Over Tangier

|

| Janice Law |

Author Janice Law opens Moon Over Tangier with protagonist/narrator Francis Bacon bruised, bleeding, and wearing little more than fishnet stockings in the muddy Berkshire countryside. David, his partner, has once again erupted into a rage that the artist escaped only by running outside after a well-placed kick forced David to release the knife he held at Bacon’s throat.

Third in the Francis Bacon trilogy following The Fires of London, a finalist in the 2012 Lambda Award for Gay Mysteries; and The Prisoner of the Riviera, winner of the 2013 Lambda Award Best Gay Mystery, Moon Over Tangier will impress many readers as even better than the first two.

Eager to escape his situation and obsessed with David, Bacon follows him to Tangier. David—charming when he’s relaxed and mellowed with a happy level of alcohol intake—invites Bacon to a party where he introduces Bacon to his friend Richard who shows them a Picasso he has purchased. Unfortunately, Bacon realizes the painting is a copy, possibly an outright forgery. His telling Richard this leads to Bacon becoming an unwilling undercover agent for the police and barely escaping with his life after being locked in a closet while another man is killed.

Caught up in murders, art forgery, and espionage, Bacon is captured and tortured physically by foreign agents and mentally by his love for David and David’s treatment of him, which he sums up in the words, “David liked me, but he didn’t love me.”

This reader especially liked Francis Bacon’s witty narrator’s voice and appreciated Law’s treatment of David, “a brave, twisted man, half-ruined by the war and busy completing the destruction.” Law’s word choices are consistent with the post-war forties, and at no place do we see the term PTSD, but David is clearly a victim of that condition. In keeping with the time of the setting, Bacon and David do not flaunt their homosexuality, but they do “cavort,” the narrator’s term for their attraction to handsome beach boys and casual sexual encounters, which are not described in detail.

Janice Law's Francis Bacon, the main character, is based on the real Francis Bacon, an Irish-born British bon vivant known for raw emotional imagery in his paintings. Throughout Moon Over Tangier the fictional character's references to his art are consistent with the real Bacon's isolated male heads of the 1940s and screaming popes of the 1950s. In previous Francis Bacon mysteries, his earlier life and close relationship with his nanny are historically accurate as are the descriptions of locations during the designated time periods in all three books.

It is not, however, necessary to know anything about the real Francis Bacon to appreciate reading about Law's fictional version, nor is it necessary to read the first two novels before Moon Over Tangier. This book works just as well as a stand-alone, though anyone who reads this third in the trilogy first will probably then read The Fires of London and The Prisoner of the Riviera.

Historical fiction has not been my favorite genre, but in Moon Over Tangier, Janice Law weaves in the historical facts so skillfully that I am not distracted from the adventure and mystery of the story. With the talent and expertise that Law has displayed in previous works, her writing captures me and takes me into a less than familiar world where the setting and characters become real and exciting. I read Moon Over Tangier for entertainment, and Janice Law's Francis Bacon entertains me five stars.

Moon Over Tangier

Author: Janice Law

Publisher: Mysterious Press.com/Open Road

ISBN: 978-1-4976-4199-5

Until we meet again, take care of … you (and read this great new book by Janice!)

Labels:

Fran Rizer,

Francis Bacon,

historical fiction,

history,

Janice Law

Location:

Columbia, SC, USA

12 June 2014

Boundaries

by Janice Law

by Janice Law

The first week in June, The Prisoner of the Riviera won a Lambda award for best gay mystery, a very pleasant surprise that has gotten me thinking about proper fictional subjects and about the way that what’s considered suitable is altered over time. Although any writer worth her salt believes implicitly– if not explicitly– in the Muse, that tricky little goddess is not immune to changes in opportunity or fashion.

I doubt very much that she would have offered me Francis Bacon as a good bet when I first started out in the 1970’s, even if the Anglo-Irish painter had been racking up the multi-million dollar sales that now benefit his heirs and fancy galleries. One only has to read Raymond Chandler, whom I otherwise much admire, to see how homophobic and bigoted his Philip Marlowe was. I suspect that Francis, breezy and witty and quite upfront about his recreations, would have been a tough sell.

My Muse, however, did have a wayward streak, and she initially suggested that my Anna Peters – one, I think, of the very first female working class sleuths– be a woman with children. Fortunately, she didn’t push that idea. Although commonplace today, in the late 70’s the world was no more ready for a woman investigator with children than Conan Doyle’s audience was for the Tale of the Giant Sumatra Rat. Anna emerged in print shorn of family and remained childless through nine adventures.

Times change. Certain topics are no longer off limits for women writers. Pat Barker has written gripping novels about World War One and the idea that nice women don’t write about sex has now been dead for at least a generation. During the same time, however, other divisions emerged. Older readers will still remember the uproar that The Confessions of Nat Turner aroused, because Styron was a white novelist writing about a black historical figure. Like attacks on male novelists like Norman Mailer who were seen as misogynistic, the controversy over The Confessions was an attempt by a marginalized group to control, or at least to influence, the way it was being depicted.

With the emergence of best selling authors from a variety of hitherto ignored groups, image control is perhaps a less pressing concern, but it does linger around the fringes of literary life. Who gets to draw the pictures? Who gets to present The Other, whatever that other might be, and how neatly can– or should– any society pigeonhole its writers?

These are questions properly for philosophers and political thinkers. The writer is a different beast altogether and should, I submit, properly stake as much territory as she can get away with. And create as diverse a set of characters as the Muse allows.

So why Francis? Why now?

One, practical concern: historical characters as detectives are currently popular. OK. Once in a while it is good to pay attention to fashion. Two, he started talking to me. Did I ignore him at first? You bet. Did I really want to research gay life in London after the Second World War? Not particularly. Was I enchanted with his work? Not really, although I thought– and still think– it very original and a quite brilliant example of a painter making even his weaknesses work for him. Did I find his sexual habits, not his orientation but his masochistic propensities, intriguing? I did not.

And yet, when you come right down to it, even a man as promiscuous as Bacon, even one as fond of drink and gambling and rough trade spent most of his time in less exotic pursuits. He worked hard and he was a strict critic of his own work. Alas that he destroyed much of his early work, for what survives is immensely interesting, and he slashed inadequate canvases both early and late. He lived with his old nanny and read the crime news to her when her sight started to go. And she, despite incipient blindness, went shop-lifting for them when they were broke.

He had friends, a number of them women, and patrons and artistic enemies. He made acquaintance with the notorious Kray Brothers and dabbled in an underground gambling venture and took holidays in the sun with his respectable lover.

In short, he was a man in full, a complicated human being, and as such he escapes the neat pigeonholes that society favors– and relies on. So, why Francis Bacon?

Why not?

The first week in June, The Prisoner of the Riviera won a Lambda award for best gay mystery, a very pleasant surprise that has gotten me thinking about proper fictional subjects and about the way that what’s considered suitable is altered over time. Although any writer worth her salt believes implicitly– if not explicitly– in the Muse, that tricky little goddess is not immune to changes in opportunity or fashion.

I doubt very much that she would have offered me Francis Bacon as a good bet when I first started out in the 1970’s, even if the Anglo-Irish painter had been racking up the multi-million dollar sales that now benefit his heirs and fancy galleries. One only has to read Raymond Chandler, whom I otherwise much admire, to see how homophobic and bigoted his Philip Marlowe was. I suspect that Francis, breezy and witty and quite upfront about his recreations, would have been a tough sell.

My Muse, however, did have a wayward streak, and she initially suggested that my Anna Peters – one, I think, of the very first female working class sleuths– be a woman with children. Fortunately, she didn’t push that idea. Although commonplace today, in the late 70’s the world was no more ready for a woman investigator with children than Conan Doyle’s audience was for the Tale of the Giant Sumatra Rat. Anna emerged in print shorn of family and remained childless through nine adventures.

Times change. Certain topics are no longer off limits for women writers. Pat Barker has written gripping novels about World War One and the idea that nice women don’t write about sex has now been dead for at least a generation. During the same time, however, other divisions emerged. Older readers will still remember the uproar that The Confessions of Nat Turner aroused, because Styron was a white novelist writing about a black historical figure. Like attacks on male novelists like Norman Mailer who were seen as misogynistic, the controversy over The Confessions was an attempt by a marginalized group to control, or at least to influence, the way it was being depicted.

With the emergence of best selling authors from a variety of hitherto ignored groups, image control is perhaps a less pressing concern, but it does linger around the fringes of literary life. Who gets to draw the pictures? Who gets to present The Other, whatever that other might be, and how neatly can– or should– any society pigeonhole its writers?

These are questions properly for philosophers and political thinkers. The writer is a different beast altogether and should, I submit, properly stake as much territory as she can get away with. And create as diverse a set of characters as the Muse allows.

So why Francis? Why now?

One, practical concern: historical characters as detectives are currently popular. OK. Once in a while it is good to pay attention to fashion. Two, he started talking to me. Did I ignore him at first? You bet. Did I really want to research gay life in London after the Second World War? Not particularly. Was I enchanted with his work? Not really, although I thought– and still think– it very original and a quite brilliant example of a painter making even his weaknesses work for him. Did I find his sexual habits, not his orientation but his masochistic propensities, intriguing? I did not.

And yet, when you come right down to it, even a man as promiscuous as Bacon, even one as fond of drink and gambling and rough trade spent most of his time in less exotic pursuits. He worked hard and he was a strict critic of his own work. Alas that he destroyed much of his early work, for what survives is immensely interesting, and he slashed inadequate canvases both early and late. He lived with his old nanny and read the crime news to her when her sight started to go. And she, despite incipient blindness, went shop-lifting for them when they were broke.

He had friends, a number of them women, and patrons and artistic enemies. He made acquaintance with the notorious Kray Brothers and dabbled in an underground gambling venture and took holidays in the sun with his respectable lover.

In short, he was a man in full, a complicated human being, and as such he escapes the neat pigeonholes that society favors– and relies on. So, why Francis Bacon?

Why not?

Labels:

Janice Law,

Lambda Awards,

Pat Barker,

William Styron

Location:

Hampton, CT, USA

05 March 2014

A Good Day For Bad Days

After I wrote this piece the Short Mystery Fiction Society announced the finalists for this year's Derringer Awards. I am delighted to say that one of them is my "The Present," which appeared in The Strand Magazine. If you are interested I wrote about the story here.

I am pleased to report that the May issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, on newsstands now, features my twenty-third story for that august journal. I am even happier to report that number twenty-four was purchased in February. So I may have a three-Hitchcock year twice in a row.

(And I am delighted to see that two fellow SleuthSayers are on the cover. Congrats John and Janice!)

But let's talk about where the idea for lucky twenty-three came from. Typically a story idea for me comes like a bolt from the blue, or it accumulates a piece at a time. In this case, oddly enough, it did both.

You see, I had an idea for quite some time, but I lacked a place to put it. I needed a setting where a group of strangers would be in close proximity and I couldn't find the right one. Then, one day, I happened to be waiting in line for an estate sale - the very one I described here -- and I realized that that was the perfect setting. I grabbed my notebook and started scribbling down all the possible ways I could use an estate sale in my story.

Then I needed a character, specifically a police officer who would be attending the sale as a customer. And for my story to work he needed to be a specific kind of policeman. Not to put too fine a point on it, I needed a cop who was not very good at his job.

Then I

realized that I already had one. A long time ago I had written a

story called "A Bad Day for Pink and Yellow Shirts." It described

three men getting involved in a disastrous mess and having only a few

minutes to come up with an explanation that made all of them come out

looking good. One of the characters was Officer Kite, a patrolman

who had spent almost as much of his career suspended for various

screw-ups as he had on the beat.

Just the man for the job. I quickly enlisted him and realized that I had the title for my story: "A Bad Day For Bargain Hunters." Like the first tale, this one is also told from multiple viewpoints.

And here is another odd relationship between the stories. "Shirts" appeared in Hitchcock's in May 2004. "Hunters" is showing up ten years later to the month. Odder still is that my last publication is a sequel to a different tale that appeared in Hitchcock's almost exactly ten years earlier. I seem to have a new habit: a decadal series. Decadent? Decimated?

I hope you enjoy the story, anyway.

I am pleased to report that the May issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, on newsstands now, features my twenty-third story for that august journal. I am even happier to report that number twenty-four was purchased in February. So I may have a three-Hitchcock year twice in a row.

(And I am delighted to see that two fellow SleuthSayers are on the cover. Congrats John and Janice!)

But let's talk about where the idea for lucky twenty-three came from. Typically a story idea for me comes like a bolt from the blue, or it accumulates a piece at a time. In this case, oddly enough, it did both.

You see, I had an idea for quite some time, but I lacked a place to put it. I needed a setting where a group of strangers would be in close proximity and I couldn't find the right one. Then, one day, I happened to be waiting in line for an estate sale - the very one I described here -- and I realized that that was the perfect setting. I grabbed my notebook and started scribbling down all the possible ways I could use an estate sale in my story.

Then I needed a character, specifically a police officer who would be attending the sale as a customer. And for my story to work he needed to be a specific kind of policeman. Not to put too fine a point on it, I needed a cop who was not very good at his job.

Just the man for the job. I quickly enlisted him and realized that I had the title for my story: "A Bad Day For Bargain Hunters." Like the first tale, this one is also told from multiple viewpoints.

And here is another odd relationship between the stories. "Shirts" appeared in Hitchcock's in May 2004. "Hunters" is showing up ten years later to the month. Odder still is that my last publication is a sequel to a different tale that appeared in Hitchcock's almost exactly ten years earlier. I seem to have a new habit: a decadal series. Decadent? Decimated?

I hope you enjoy the story, anyway.

Labels:

AHMM,

Alfred Hitchcock,

Floyd,

Janice Law,

mystery magazine,

story

30 January 2014

Review: Voyage of Strangers by Elizabeth Zelvin

by Janice Law

It’s always nice to see writers try something new and different and out of their comfort zone. Elizabeth Zelvin, our Sleuthsayers colleague, has taken a big step away from her very New York detective Bruce Kohler and his friends in therapy and in recovery to tackle the lethal adventures and messy politics of Columbus’s New World voyages.

Most of us learned about Columbus from the famous rhyme and the annual school holiday. The rest of the curriculum on the Conquistadores focused on the clashes with the Aztecs and Mayans and on the destruction of the Inca Empire. But exploitation, pillage and genocide hit the New World earlier, with what became the disastrous landing of the famous flotilla on the Caribbean islands.

So devastating was the meeting between Europeans and the native Taino and Caribe, that very little of their culture now survives. Ironically, a voyage that set out to find the East Indies for trading purposes degenerated into a scramble for gold, and when that proved thin on the ground, for slaves.

Zelvin’s Voyage of Strangers finds a way into this now obscure episode via a character who is a stranger to both the Spanish crew and the natives they encounter. Diego, a teenaged sailor in the Admiral's fleet, has a big secret: he is an unconverted Jew and as such vulnerable to arrest and death at the hands of the Inquisition.

Zelvin says that Diego “came knocking on the inside of my head in the middle of the night, demanding that I tell his story.” The young sailor showed up originally for Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine stories, but he hung around until she gave him a novel of his own. Voyage of Strangers begins with him covertly saying his prayers up in the crow’s nest of the Santa Maria, then returns him to the scarcely less dangerous Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella, where the Moors have recently been defeated and enslaved, and the Jews, the next target, forced to flee, convert or perish at the stake.

Diego is protected by Admiral Columbus, a friend of his father’s, and he hopes to make money in the New World, thus recouping his family’s lost fortune. For the moment, he puts aside some nagging worries about the treatment of Taino friends and focuses on getting his younger sister, Rachel, safely out of Seville and off to their parents living in exile in Florence.

This proves easier said than done. Diego is a paragon of an older brother, but Rachel, though charming in every way, is a handful. She’s sure that she can pass as Christian, having spent some time hiding in a convent; what’s worse is that she’s also sure she can pass as a boy, and she fully intends to accompany Diego on the Admiral’s next voyage.

The novel really is in two parts, the Spanish segment, involved with the preparations for the second and much larger expedition to the New World, the dangers of the Inquisition, and the difficulties of traveling safely with a lively girl of thirteen, and the sea voyage and the delights and terrors of the islands.

The island segment is more gripping and unusual. Zelvin, who has visited in the Caribbean and knows tropical climates well after a time in Côte d’Ivoire as a Peace Corps volunteer, does a good job of imagining the lush island with its spectacular hills and waterfalls, abundant food and generally easy living. Alas, the beauty of the island is soon tarnished by the demands of European military architecture and an obsessive pursuit of gold that eventually corrupts even Diego’s admired Admiral Columbus. For a time, however, the brother and sister enjoy the freedom of the forest and the friendship of the Taino, whose generous and easy going culture will prove no match for rapacious guests operating in a completely different economic system.

Voyage of Strangers is very good on the tragic clash of cultures that ensues. Diego, particularly, is almost preternaturally understanding and broad-minded, although his own experience as a hunted minority does give him an insight into the plight of the Taino.

The story of the young people and their adventures acts somewhat to ameliorate what is otherwise an unrelievedly grim account of the conquest of the Caribbean. Diego and Rachel and their Taino friend Hutia are good company. The island, at least initially, is an adventure playground, and the novel, as well as its quite modern characters, is both suitable and historically enlightening for teen as well as adult readers.

Most of us learned about Columbus from the famous rhyme and the annual school holiday. The rest of the curriculum on the Conquistadores focused on the clashes with the Aztecs and Mayans and on the destruction of the Inca Empire. But exploitation, pillage and genocide hit the New World earlier, with what became the disastrous landing of the famous flotilla on the Caribbean islands.

So devastating was the meeting between Europeans and the native Taino and Caribe, that very little of their culture now survives. Ironically, a voyage that set out to find the East Indies for trading purposes degenerated into a scramble for gold, and when that proved thin on the ground, for slaves.

Zelvin’s Voyage of Strangers finds a way into this now obscure episode via a character who is a stranger to both the Spanish crew and the natives they encounter. Diego, a teenaged sailor in the Admiral's fleet, has a big secret: he is an unconverted Jew and as such vulnerable to arrest and death at the hands of the Inquisition.

Zelvin says that Diego “came knocking on the inside of my head in the middle of the night, demanding that I tell his story.” The young sailor showed up originally for Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine stories, but he hung around until she gave him a novel of his own. Voyage of Strangers begins with him covertly saying his prayers up in the crow’s nest of the Santa Maria, then returns him to the scarcely less dangerous Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella, where the Moors have recently been defeated and enslaved, and the Jews, the next target, forced to flee, convert or perish at the stake.

Diego is protected by Admiral Columbus, a friend of his father’s, and he hopes to make money in the New World, thus recouping his family’s lost fortune. For the moment, he puts aside some nagging worries about the treatment of Taino friends and focuses on getting his younger sister, Rachel, safely out of Seville and off to their parents living in exile in Florence.

This proves easier said than done. Diego is a paragon of an older brother, but Rachel, though charming in every way, is a handful. She’s sure that she can pass as Christian, having spent some time hiding in a convent; what’s worse is that she’s also sure she can pass as a boy, and she fully intends to accompany Diego on the Admiral’s next voyage.

The novel really is in two parts, the Spanish segment, involved with the preparations for the second and much larger expedition to the New World, the dangers of the Inquisition, and the difficulties of traveling safely with a lively girl of thirteen, and the sea voyage and the delights and terrors of the islands.

The island segment is more gripping and unusual. Zelvin, who has visited in the Caribbean and knows tropical climates well after a time in Côte d’Ivoire as a Peace Corps volunteer, does a good job of imagining the lush island with its spectacular hills and waterfalls, abundant food and generally easy living. Alas, the beauty of the island is soon tarnished by the demands of European military architecture and an obsessive pursuit of gold that eventually corrupts even Diego’s admired Admiral Columbus. For a time, however, the brother and sister enjoy the freedom of the forest and the friendship of the Taino, whose generous and easy going culture will prove no match for rapacious guests operating in a completely different economic system.

Voyage of Strangers is very good on the tragic clash of cultures that ensues. Diego, particularly, is almost preternaturally understanding and broad-minded, although his own experience as a hunted minority does give him an insight into the plight of the Taino.

The story of the young people and their adventures acts somewhat to ameliorate what is otherwise an unrelievedly grim account of the conquest of the Caribbean. Diego and Rachel and their Taino friend Hutia are good company. The island, at least initially, is an adventure playground, and the novel, as well as its quite modern characters, is both suitable and historically enlightening for teen as well as adult readers.

Labels:

Caribbean,

Columbus,

Elizabeth Zelvin,

Janice Law,

Taino

Location:

Hampton, CT, USA

02 January 2014

The Prisoner of the Riviera

by Eve Fisher

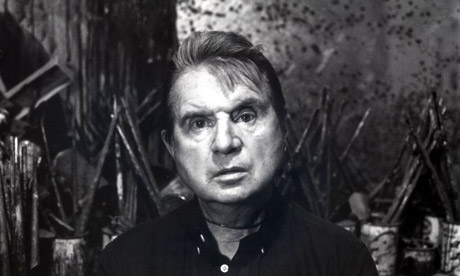

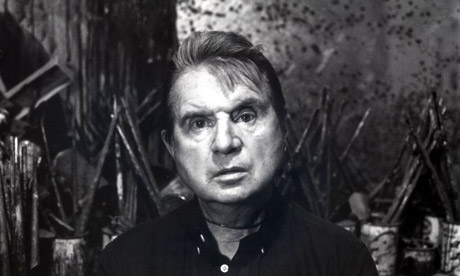

First of all, meet Janice Law:

No, not that one, this one:

No, not that one, this one:

Francis Bacon, artist. Francis Bacon, gambler. Francis Bacon, bon vivant. Francis Bacon, gay, asthmatic, Irish, auto-didact, devoted to his Nanny (who lived with him until her death in 1951), and an absolute mess (his studio, by all accounts, was like something out of "Hoarders"). Francis Bacon, who must be howling over the whopping 142 million pounds paid for his portrait of Lucian Freud last year (the most ever paid for any work of art), especially since he never made anything like that sum in his life, despite his taste for high low life. Let's just say the boy lived above his means, and that's part of what gets him in trouble.

Especially in Janice Law's "The Prisoner of the Riviera", the second of her Francis Bacon series (and if you have not yet read "The Fires of London", go and get it immediately). Francis is back, in all his dark, louche, sardonic, hungry, artistic, reckless glory.

Did I mention he's a gambler? Well, in post-WW2 Britain, it's practically the only fun you can have (all right, there is Albert, his lover...), but Francis' luck hasn't been good. And it doesn't improve when he sees a Frenchman shot in front of him as he and Albert head home. Francis leaps to help, but the man - Monsieur Renard - dies. And then Joubert, the owner of the gambling den, makes Francis an offer he can't refuse: take a package to Madame Renard on the Riviera. In exchange, all of Francis' gambling debts will be forgiven. Well, Francis' debts are high, and he and Albert and Nan had already planned to go to Monte Carlo for a vacation ("A solemn promise, dear boy"), so why not. So off they go, Francis, Albert, and Nan, to eat and drink and gamble and relax in the sun and, eventually, fulfill his commission...

Now, to those of us who know our French fairytales, the name Renard hints that this is not going to be all pate de foie gras and Chateau Lafite, although Francis does his best to consume as much of the good stuff as he can. And indeed, when Francis (eventually) goes to fulfill his commission on a hot, lazy, dusty day, things go south remarkably quickly. The house is sinister, the widow unusual, and two thugs seem to be following him with ill intent. Two days later, he is the prime suspect in the murder of Madame Renard - after all, everyone knows that a foreigner, especially a British foreigner, would be the obvious suspect in a small resort town - even though the dead woman does not look at all like the Madame Renard to whom he handed that mysterious package... And the package has disappeared. And "Renard" used to be the codeword for various operations, some of which had to do with the Resistance... And everyone wants him to "help" them with their inquiries - licit or illicit. Thankfully, the food is good, the wine is wonderful, and Pierre the bicyclist is delightful... until all hell breaks loose. Again.

Now, to those of us who know our French fairytales, the name Renard hints that this is not going to be all pate de foie gras and Chateau Lafite, although Francis does his best to consume as much of the good stuff as he can. And indeed, when Francis (eventually) goes to fulfill his commission on a hot, lazy, dusty day, things go south remarkably quickly. The house is sinister, the widow unusual, and two thugs seem to be following him with ill intent. Two days later, he is the prime suspect in the murder of Madame Renard - after all, everyone knows that a foreigner, especially a British foreigner, would be the obvious suspect in a small resort town - even though the dead woman does not look at all like the Madame Renard to whom he handed that mysterious package... And the package has disappeared. And "Renard" used to be the codeword for various operations, some of which had to do with the Resistance... And everyone wants him to "help" them with their inquiries - licit or illicit. Thankfully, the food is good, the wine is wonderful, and Pierre the bicyclist is delightful... until all hell breaks loose. Again.

Francis quickly discovers that he has walked into a world that is just as haunted by World War II as Britain, only differently. The Riviera spent its war occupied by collaborators and resistance, fascists and communists, counterfeiters and criminals, and far too many of them are still there, still feuding, still fighting, still procuring, masquerading, lying, killing... (the bodies are piling up!) And far too many of them want Francis dead.

"The Prisoner of the Riviera" is a fast-paced ride that has as many twists and turns as a Riviera mountain road. And Francis is just the man to tell the story: witty, sarcastic, honest, an artist whose interest is always in the unusual, a lover who makes no bones about who he is, a man who knows everything about the dark side of life. Read it now, and then wait, breathlessly, for the next installment of Francis Bacon, channeled through Janice Law!

"The Prisoner of the Riviera" is a fast-paced ride that has as many twists and turns as a Riviera mountain road. And Francis is just the man to tell the story: witty, sarcastic, honest, an artist whose interest is always in the unusual, a lover who makes no bones about who he is, a man who knows everything about the dark side of life. Read it now, and then wait, breathlessly, for the next installment of Francis Bacon, channeled through Janice Law!

Secondly, meet Francis Bacon:

No, not that one, this one:

No, not that one, this one:

Francis Bacon, artist. Francis Bacon, gambler. Francis Bacon, bon vivant. Francis Bacon, gay, asthmatic, Irish, auto-didact, devoted to his Nanny (who lived with him until her death in 1951), and an absolute mess (his studio, by all accounts, was like something out of "Hoarders"). Francis Bacon, who must be howling over the whopping 142 million pounds paid for his portrait of Lucian Freud last year (the most ever paid for any work of art), especially since he never made anything like that sum in his life, despite his taste for high low life. Let's just say the boy lived above his means, and that's part of what gets him in trouble.

Especially in Janice Law's "The Prisoner of the Riviera", the second of her Francis Bacon series (and if you have not yet read "The Fires of London", go and get it immediately). Francis is back, in all his dark, louche, sardonic, hungry, artistic, reckless glory.

|

| Monte Carlo Casino |

Now, to those of us who know our French fairytales, the name Renard hints that this is not going to be all pate de foie gras and Chateau Lafite, although Francis does his best to consume as much of the good stuff as he can. And indeed, when Francis (eventually) goes to fulfill his commission on a hot, lazy, dusty day, things go south remarkably quickly. The house is sinister, the widow unusual, and two thugs seem to be following him with ill intent. Two days later, he is the prime suspect in the murder of Madame Renard - after all, everyone knows that a foreigner, especially a British foreigner, would be the obvious suspect in a small resort town - even though the dead woman does not look at all like the Madame Renard to whom he handed that mysterious package... And the package has disappeared. And "Renard" used to be the codeword for various operations, some of which had to do with the Resistance... And everyone wants him to "help" them with their inquiries - licit or illicit. Thankfully, the food is good, the wine is wonderful, and Pierre the bicyclist is delightful... until all hell breaks loose. Again.

Now, to those of us who know our French fairytales, the name Renard hints that this is not going to be all pate de foie gras and Chateau Lafite, although Francis does his best to consume as much of the good stuff as he can. And indeed, when Francis (eventually) goes to fulfill his commission on a hot, lazy, dusty day, things go south remarkably quickly. The house is sinister, the widow unusual, and two thugs seem to be following him with ill intent. Two days later, he is the prime suspect in the murder of Madame Renard - after all, everyone knows that a foreigner, especially a British foreigner, would be the obvious suspect in a small resort town - even though the dead woman does not look at all like the Madame Renard to whom he handed that mysterious package... And the package has disappeared. And "Renard" used to be the codeword for various operations, some of which had to do with the Resistance... And everyone wants him to "help" them with their inquiries - licit or illicit. Thankfully, the food is good, the wine is wonderful, and Pierre the bicyclist is delightful... until all hell breaks loose. Again. Francis quickly discovers that he has walked into a world that is just as haunted by World War II as Britain, only differently. The Riviera spent its war occupied by collaborators and resistance, fascists and communists, counterfeiters and criminals, and far too many of them are still there, still feuding, still fighting, still procuring, masquerading, lying, killing... (the bodies are piling up!) And far too many of them want Francis dead.

"The Prisoner of the Riviera" is a fast-paced ride that has as many twists and turns as a Riviera mountain road. And Francis is just the man to tell the story: witty, sarcastic, honest, an artist whose interest is always in the unusual, a lover who makes no bones about who he is, a man who knows everything about the dark side of life. Read it now, and then wait, breathlessly, for the next installment of Francis Bacon, channeled through Janice Law!

"The Prisoner of the Riviera" is a fast-paced ride that has as many twists and turns as a Riviera mountain road. And Francis is just the man to tell the story: witty, sarcastic, honest, an artist whose interest is always in the unusual, a lover who makes no bones about who he is, a man who knows everything about the dark side of life. Read it now, and then wait, breathlessly, for the next installment of Francis Bacon, channeled through Janice Law!

Labels:

Eve Fisher,

Francis Bacon,

French Resistance,

Janice Law

26 December 2013

Bridges

by Janice Law

Former President Bill Clinton used to like to talk about “bridges to the 21st century,” a rhetorical flourish which usually indicated investment in some new technology or educational technique. This was, of course, back in those simpler and unenlightened days of the 20th century when politicians were keen on building for the future instead of for a retreat to the 19th century or earlier.

However, the idea of bridges to the future got me thinking about bridges in writing, which like the President’s bridges, tend to rely a good deal on imagination and guesswork. In particular, every writer knows the delicate suspension construction that extends between the two commands of imaginative writing: write what you know and write what you want to learn.

In some cases, this particular bridge needs to be exceptionally sturdy. I’m currently reading Adam Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize winning The Orphan Master’s Son, set in North Korea. Even with three big grants and a trip to the Hermit State, conjuring up a plausible protagonist and a plausible Communist Korea must have been a toughie.

In some cases, this particular bridge needs to be exceptionally sturdy. I’m currently reading Adam Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize winning The Orphan Master’s Son, set in North Korea. Even with three big grants and a trip to the Hermit State, conjuring up a plausible protagonist and a plausible Communist Korea must have been a toughie.

Mystery writing has its challenges, too. Although a number of my Sleuthsayers colleagues have worked in either law enforcement, the military, or social work, I would guess that most writers of mysteries, suspense, and thrillers probably lead, like me, distinctly un-thrilling lives. Even those with professional experience must need some little bridges of their own. Consider the thriller which has gone from tales of intrepid secret agents on the lam with the essential microfilm or sub base plans to the present steroidal concoctions where saving the planet is not too big a challenge.

More realistic work branches out in a different way. I recently enjoyed Tuesday’s Gone by the husband and wife team that writes as Nicci French. The book’s strong suit is definitely its fine characterizations, especially of psychotherapist, doctor, and police consultant Frieda Klein. I dare say that the details of the plot, though very satisfying, are implausibly complex if one is being strictly realistic. The book works well, however, because of the strong characterizations. Our interest in the personalities involved and our anxiety to find out what happens carry us nicely over convenient coincidences and timely bursts of sleuthing inspiration. A bridge, indeed.

On a more modest level, I’ve been looking for literary bridges in a new Francis Bacon mystery, the third in what I projected from the start as a trilogy. This one is set in London but also in Tangier, in what was in the 1950’s still the International Zone administered by a coalition of European powers. Problem: I’ve never been there. Solution: a goodly amount of research, plus memories of the French and Italian rivieras, which have a similar landscape and climate.

On a more modest level, I’ve been looking for literary bridges in a new Francis Bacon mystery, the third in what I projected from the start as a trilogy. This one is set in London but also in Tangier, in what was in the 1950’s still the International Zone administered by a coalition of European powers. Problem: I’ve never been there. Solution: a goodly amount of research, plus memories of the French and Italian rivieras, which have a similar landscape and climate.

Was this satisfactory? Only time will tell, as Doonesbury’s Roland Hedley likes to say, but I think moderately satisfactory, since Francis is an urban man without much eye for landscape. He was a painter focused on internal, not external, weather, so it was plausible to keep his focus on his relationships with other people and his observations of their interactions.

Of course, his relationships with other people, particularly the love of his life and his real fatal man, an alcoholic ex-RAF pilot, presented other challenges. In particular, how to write about Francis’s violent masochistic relationship with his lover in such a way as not to destroy the tone of the whole and the emphasis on what is a strictly imaginary adventure.

After what is now three novels about Francis, I think it is safe to say that he has evolved into a fictional character, resembling the real man, but with a tone of his own, which, as befitting my personality, is a bit lighter in spirit than the genius painter of very dark interiors. The real man was said to be camp but tough, very tough, indeed, and though a pessimist, a resolute enjoyer of life’s pleasures.

I’ve written him as cheerful and ironic and given him his late, and much missed, nanny’s voice in his ear. He’s foolish, but no fool, and I guess that sums up the imaginative bridge between what I know about the real Bacon, product of research and looking at his paintings, and the imaginary character, who is free to have bizarre and somewhat absurd adventures among the sorts of thugs and spies whom the real man would probably have enjoyed.

However, the idea of bridges to the future got me thinking about bridges in writing, which like the President’s bridges, tend to rely a good deal on imagination and guesswork. In particular, every writer knows the delicate suspension construction that extends between the two commands of imaginative writing: write what you know and write what you want to learn.

In some cases, this particular bridge needs to be exceptionally sturdy. I’m currently reading Adam Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize winning The Orphan Master’s Son, set in North Korea. Even with three big grants and a trip to the Hermit State, conjuring up a plausible protagonist and a plausible Communist Korea must have been a toughie.

In some cases, this particular bridge needs to be exceptionally sturdy. I’m currently reading Adam Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize winning The Orphan Master’s Son, set in North Korea. Even with three big grants and a trip to the Hermit State, conjuring up a plausible protagonist and a plausible Communist Korea must have been a toughie.Mystery writing has its challenges, too. Although a number of my Sleuthsayers colleagues have worked in either law enforcement, the military, or social work, I would guess that most writers of mysteries, suspense, and thrillers probably lead, like me, distinctly un-thrilling lives. Even those with professional experience must need some little bridges of their own. Consider the thriller which has gone from tales of intrepid secret agents on the lam with the essential microfilm or sub base plans to the present steroidal concoctions where saving the planet is not too big a challenge.

More realistic work branches out in a different way. I recently enjoyed Tuesday’s Gone by the husband and wife team that writes as Nicci French. The book’s strong suit is definitely its fine characterizations, especially of psychotherapist, doctor, and police consultant Frieda Klein. I dare say that the details of the plot, though very satisfying, are implausibly complex if one is being strictly realistic. The book works well, however, because of the strong characterizations. Our interest in the personalities involved and our anxiety to find out what happens carry us nicely over convenient coincidences and timely bursts of sleuthing inspiration. A bridge, indeed.

On a more modest level, I’ve been looking for literary bridges in a new Francis Bacon mystery, the third in what I projected from the start as a trilogy. This one is set in London but also in Tangier, in what was in the 1950’s still the International Zone administered by a coalition of European powers. Problem: I’ve never been there. Solution: a goodly amount of research, plus memories of the French and Italian rivieras, which have a similar landscape and climate.

On a more modest level, I’ve been looking for literary bridges in a new Francis Bacon mystery, the third in what I projected from the start as a trilogy. This one is set in London but also in Tangier, in what was in the 1950’s still the International Zone administered by a coalition of European powers. Problem: I’ve never been there. Solution: a goodly amount of research, plus memories of the French and Italian rivieras, which have a similar landscape and climate.Was this satisfactory? Only time will tell, as Doonesbury’s Roland Hedley likes to say, but I think moderately satisfactory, since Francis is an urban man without much eye for landscape. He was a painter focused on internal, not external, weather, so it was plausible to keep his focus on his relationships with other people and his observations of their interactions.

Of course, his relationships with other people, particularly the love of his life and his real fatal man, an alcoholic ex-RAF pilot, presented other challenges. In particular, how to write about Francis’s violent masochistic relationship with his lover in such a way as not to destroy the tone of the whole and the emphasis on what is a strictly imaginary adventure.

After what is now three novels about Francis, I think it is safe to say that he has evolved into a fictional character, resembling the real man, but with a tone of his own, which, as befitting my personality, is a bit lighter in spirit than the genius painter of very dark interiors. The real man was said to be camp but tough, very tough, indeed, and though a pessimist, a resolute enjoyer of life’s pleasures.

I’ve written him as cheerful and ironic and given him his late, and much missed, nanny’s voice in his ear. He’s foolish, but no fool, and I guess that sums up the imaginative bridge between what I know about the real Bacon, product of research and looking at his paintings, and the imaginary character, who is free to have bizarre and somewhat absurd adventures among the sorts of thugs and spies whom the real man would probably have enjoyed.

12 December 2013

Good Character / Bad Character

by Janice Law

by Janice Law

I’ve been reading Claire Tomalin’s biography of Charles Dickens, and I was once again struck by his emotional reaction to his characters, especially to Little Nell of The Old Curiosity Shop, a typical Victorian saintly child, whose precarious situation and dodgy health provoked transatlantic anxieties. Folks actually met British steamers at the New York docks to get the latest news of this Dickens’ heroine.

Few of us will create such emotional havoc in our readers and today the internet spills the beans via blogs or Twitter. But it got me thinking about writers’ relationships with characters, in particular, with the way that some characters just write like a dream while others resist their translation to print and even when successful represent a long, hard slog.

I can hear the amateur psychologists in the background muttering about covert self portraits and sub-conscious impulses. Frankly, I hope that’s not true, because the characters that I’ve had the most trouble with are the virtuous ones, while certain weird and wicked people just jumped off the page.

Of course, evil is stock in trade for the mystery writer. But even slightly off that homicidal reservation I’ve found that the wicked make good copy. Years ago, I wrote All the King’s Ladies, an historical novel set at the court of Louis XIV and based on the Affair of the Poisons. Two particularly heinous characters, the Abbe LeSage, a defrocked priest, Black Mass celebrant, and pedophile, and Madame Voisin, abortionist, vendor of love potions, and poisoner were among the easiest characters I’ve ever written.

I might have trouble with the King, with his various ambitious ladies, or with the celebrated Police Commissioner De La Reynie but never with LeSage or Voisin, who greeted me each morning with snappy dialogue and wholly unrepentant attitudes. Given their habits, I really think I would have found them unbearable if they hadn’t also possessed a sort of gleeful energy, which makes me think that robust vitality trumps any number of other virtues – at least on the page.

Short mystery stories are the natural habitat of such types. The short story needs punch and compression, and characters need to be sharply drawn if they are to make an impact in the handful of pages allotted to them. For this reason, I have always favored either first person narratives or single point of view for the form.

But even in mysteries, evil needs to be the seasoning, not the main dish. In All the King’s Ladies, LeSage and La Voisin were minor characters, however vital, and I only occasionally, as in The Writing Workshop about a writer’s murderous search for a sympathetic editor, write a story entirely from the point of view of a cold-blooded perpetrator.

More usually, the narrator is either an observer who only gradually realizes that his or her friend or acquaintance is up to no good or else is drawn into crime by circumstances only partly beyond control. And here, I think, personal tastes and interests do sometimes surface. I found the would-be literary writer who moonlights in fantasy novels in The Ghost Writer sympathetic because he had, like most writers, little rituals to help him get into the writing mode.

The drug dealer’s girlfriend in Star of the Silver Screen lived a totally different sort of life from mine, but she shared my taste for old movies and found a surprising hiding place within movie fantasies. On the other hand, I didn’t like the heroine of The Summer of the Strangler, though I was sympathetic to her role as editor for her philandering husband. Still, she wrote very nicely, in part because she lived in the suburban Connecticut town were I spent a quarter of a century.

So what is my relationship with my characters? I don’t love them like Dickens, and I’ve only become fond enough of a couple to keep writing about them. Anna Peters ran to nine novels, and Madame Selina and her assistant Nip Tompkins look set for several more outings in the short story markets.

As for my relations with the rest, they are curious. Some writers create elaborate backstories for their characters and can tell you their genealogies and private histories. Not me. Maybe it’s an exaggerated respect for the privacy of imaginary beings, but I only know what they choose to reveal. Characters start talking to me and telling me things and I write them down. That’s about it.

Sometimes they tell me a lot and they wind up in a novel. Other times their visits are brief and end in fatality; they’re destined for short stories. To me, a good character has a distinctive voice, insinuating ideas, and mild obsession. Plus, a taste for gossiping – with me.

I’ve been reading Claire Tomalin’s biography of Charles Dickens, and I was once again struck by his emotional reaction to his characters, especially to Little Nell of The Old Curiosity Shop, a typical Victorian saintly child, whose precarious situation and dodgy health provoked transatlantic anxieties. Folks actually met British steamers at the New York docks to get the latest news of this Dickens’ heroine.

Few of us will create such emotional havoc in our readers and today the internet spills the beans via blogs or Twitter. But it got me thinking about writers’ relationships with characters, in particular, with the way that some characters just write like a dream while others resist their translation to print and even when successful represent a long, hard slog.

I can hear the amateur psychologists in the background muttering about covert self portraits and sub-conscious impulses. Frankly, I hope that’s not true, because the characters that I’ve had the most trouble with are the virtuous ones, while certain weird and wicked people just jumped off the page.

Of course, evil is stock in trade for the mystery writer. But even slightly off that homicidal reservation I’ve found that the wicked make good copy. Years ago, I wrote All the King’s Ladies, an historical novel set at the court of Louis XIV and based on the Affair of the Poisons. Two particularly heinous characters, the Abbe LeSage, a defrocked priest, Black Mass celebrant, and pedophile, and Madame Voisin, abortionist, vendor of love potions, and poisoner were among the easiest characters I’ve ever written.

I might have trouble with the King, with his various ambitious ladies, or with the celebrated Police Commissioner De La Reynie but never with LeSage or Voisin, who greeted me each morning with snappy dialogue and wholly unrepentant attitudes. Given their habits, I really think I would have found them unbearable if they hadn’t also possessed a sort of gleeful energy, which makes me think that robust vitality trumps any number of other virtues – at least on the page.

Short mystery stories are the natural habitat of such types. The short story needs punch and compression, and characters need to be sharply drawn if they are to make an impact in the handful of pages allotted to them. For this reason, I have always favored either first person narratives or single point of view for the form.

But even in mysteries, evil needs to be the seasoning, not the main dish. In All the King’s Ladies, LeSage and La Voisin were minor characters, however vital, and I only occasionally, as in The Writing Workshop about a writer’s murderous search for a sympathetic editor, write a story entirely from the point of view of a cold-blooded perpetrator.

More usually, the narrator is either an observer who only gradually realizes that his or her friend or acquaintance is up to no good or else is drawn into crime by circumstances only partly beyond control. And here, I think, personal tastes and interests do sometimes surface. I found the would-be literary writer who moonlights in fantasy novels in The Ghost Writer sympathetic because he had, like most writers, little rituals to help him get into the writing mode.

The drug dealer’s girlfriend in Star of the Silver Screen lived a totally different sort of life from mine, but she shared my taste for old movies and found a surprising hiding place within movie fantasies. On the other hand, I didn’t like the heroine of The Summer of the Strangler, though I was sympathetic to her role as editor for her philandering husband. Still, she wrote very nicely, in part because she lived in the suburban Connecticut town were I spent a quarter of a century.

So what is my relationship with my characters? I don’t love them like Dickens, and I’ve only become fond enough of a couple to keep writing about them. Anna Peters ran to nine novels, and Madame Selina and her assistant Nip Tompkins look set for several more outings in the short story markets.

As for my relations with the rest, they are curious. Some writers create elaborate backstories for their characters and can tell you their genealogies and private histories. Not me. Maybe it’s an exaggerated respect for the privacy of imaginary beings, but I only know what they choose to reveal. Characters start talking to me and telling me things and I write them down. That’s about it.

Sometimes they tell me a lot and they wind up in a novel. Other times their visits are brief and end in fatality; they’re destined for short stories. To me, a good character has a distinctive voice, insinuating ideas, and mild obsession. Plus, a taste for gossiping – with me.

Labels:

characterization,

Dickens,

Janice Law

Location:

Hampton, CT, USA

10 December 2013

Nothing Wasted

by Janice Law

by Janice Law

Thanks to Dale Andrews and Terence Faherty, who have kindly given up space so I can announce the publication today, Dec 10, of Prisoner of the Riviera, the second volume of my mystery trilogy featuring that campy bon vivant and artistic genius, Francis Bacon.

Surprisingly, since I rarely plan anything in fiction, I knew from the start that I wanted to do three novels with this character. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the trilogy involved me in the same sort of plot problems that individual novels have caused. Namely, I had a wonderful idea for the beginning: a mystery set against the London Blitz– the Blackouts, sudden death from the sky, spectacular, if dangerous, light effects, and the disorientations of a totally disrupted urban geography. Who could ask for a better setting?

And then Bacon was a character that I found irresistible if rather foreign to my own experience. He was irrepressible and pleasure loving, but hard working, too. And he lived with his old nanny, the detail that convinced me to use him in fiction.

I also had a pretty good idea about the third novel. Painful experience has taught me that it is folly to embark on a project without some idea of the ending. It’s good, if not essential, to know who the killer is, but I find I absolutely need some idea of how the concluding events are going to go down. And I did know, because, just on the cusp of real success, Bacon embarked on his great erotic passion with a dangerous ex-RAF pilot. In Tangiers, no less, the exotic height of romance. How could I go wrong with that?

The problem, as perspicacious readers will have already divined, was the dreaded middle, the getting from the brilliant idea of the opening (for who ever starts a project without the delusive conviction that this idea is really terrific?) to the clever and satisfying (we do live in hope) ending. The solution was not immediately forthcoming and volume 2 might still be just a faint literary hope if not for personal past literary history.

Over every writer’s desk, in addition to Nora Ephron’s mom’s: “Remember, dear, it’s all copy,” I would add, “Remember not every project works out” and “Nothing is wasted.” Years ago, I wrote a novel called The Countess, which borrowed some of the exploits of a real WW2 SOE agent, a Polish countess in exile. I did a lot of research. I read a lot of books. I visited the Imperial War Museum in London. I even made an attempt at beginning Polish.

But just as sometimes a piece one dashes off turns out to be very good, so sometimes one’s heart’s blood is not enough. The Countess was published to small acclaim and smaller sales and I was left with a working knowledge of the French Underground and SOE circuits, plus acquaintance with the toxic politics of Vichy and the right-wing Milice.

Years passed. Although I forgot, as I tend to do, the names of agents and the dates of significant actions, a notion of the infernal complexity of war time France remained, along with the conviction that the post-war must have been a very confusing and often dangerous place.

When I recalled that Francis’s lover had promised him a gambling trip to France after the war, I had the ah-ha moment. The real Bacon, his lover, and his old Nan had actually gone to France. That was good. And what was better was that I could invent a whole range of people who had scores to settle and secrets to hide. What better environment for Francis, who does have a knack for smelling out trouble?

The French setting of Prisoner of the Riviera also enabled me to add one of my passions to the story, as very soon after the war, the French resumed the Tour de France, still the world’s most glamorous bike race. Handsome young men in bike shorts seemed to me to be just the ticket for a vacationing Francis Bacon, and having given him all sorts of obstacles and miseries, it seemed only fair to let him indulge in a little romance.

Finally, we had spent holidays in France, a number of them in the south, and the sights and sounds of the Riviera have lingered in my mind. With both the physical and emotional setting of the novel well in hand, it remained only for me to trust to the Muse to come up with the incidents. She complied and Prisoner of the Riviera, in which in best mystery novel fashion, the hero, having survived Fires of London goes on vacation and finds himself in the soup, was the result.

Thanks to Dale Andrews and Terence Faherty, who have kindly given up space so I can announce the publication today, Dec 10, of Prisoner of the Riviera, the second volume of my mystery trilogy featuring that campy bon vivant and artistic genius, Francis Bacon.

Surprisingly, since I rarely plan anything in fiction, I knew from the start that I wanted to do three novels with this character. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the trilogy involved me in the same sort of plot problems that individual novels have caused. Namely, I had a wonderful idea for the beginning: a mystery set against the London Blitz– the Blackouts, sudden death from the sky, spectacular, if dangerous, light effects, and the disorientations of a totally disrupted urban geography. Who could ask for a better setting?

And then Bacon was a character that I found irresistible if rather foreign to my own experience. He was irrepressible and pleasure loving, but hard working, too. And he lived with his old nanny, the detail that convinced me to use him in fiction.

I also had a pretty good idea about the third novel. Painful experience has taught me that it is folly to embark on a project without some idea of the ending. It’s good, if not essential, to know who the killer is, but I find I absolutely need some idea of how the concluding events are going to go down. And I did know, because, just on the cusp of real success, Bacon embarked on his great erotic passion with a dangerous ex-RAF pilot. In Tangiers, no less, the exotic height of romance. How could I go wrong with that?

The problem, as perspicacious readers will have already divined, was the dreaded middle, the getting from the brilliant idea of the opening (for who ever starts a project without the delusive conviction that this idea is really terrific?) to the clever and satisfying (we do live in hope) ending. The solution was not immediately forthcoming and volume 2 might still be just a faint literary hope if not for personal past literary history.

Over every writer’s desk, in addition to Nora Ephron’s mom’s: “Remember, dear, it’s all copy,” I would add, “Remember not every project works out” and “Nothing is wasted.” Years ago, I wrote a novel called The Countess, which borrowed some of the exploits of a real WW2 SOE agent, a Polish countess in exile. I did a lot of research. I read a lot of books. I visited the Imperial War Museum in London. I even made an attempt at beginning Polish.

But just as sometimes a piece one dashes off turns out to be very good, so sometimes one’s heart’s blood is not enough. The Countess was published to small acclaim and smaller sales and I was left with a working knowledge of the French Underground and SOE circuits, plus acquaintance with the toxic politics of Vichy and the right-wing Milice.

Years passed. Although I forgot, as I tend to do, the names of agents and the dates of significant actions, a notion of the infernal complexity of war time France remained, along with the conviction that the post-war must have been a very confusing and often dangerous place.

When I recalled that Francis’s lover had promised him a gambling trip to France after the war, I had the ah-ha moment. The real Bacon, his lover, and his old Nan had actually gone to France. That was good. And what was better was that I could invent a whole range of people who had scores to settle and secrets to hide. What better environment for Francis, who does have a knack for smelling out trouble?

The French setting of Prisoner of the Riviera also enabled me to add one of my passions to the story, as very soon after the war, the French resumed the Tour de France, still the world’s most glamorous bike race. Handsome young men in bike shorts seemed to me to be just the ticket for a vacationing Francis Bacon, and having given him all sorts of obstacles and miseries, it seemed only fair to let him indulge in a little romance.

Finally, we had spent holidays in France, a number of them in the south, and the sights and sounds of the Riviera have lingered in my mind. With both the physical and emotional setting of the novel well in hand, it remained only for me to trust to the Muse to come up with the incidents. She complied and Prisoner of the Riviera, in which in best mystery novel fashion, the hero, having survived Fires of London goes on vacation and finds himself in the soup, was the result.

Labels:

Francis Bacon,

Janice Law

Location:

Hampton, CT, USA

22 August 2013

Going to Great (or Short) Lengths

by Janice Law

Appearing in a volume of short mysteries, Kwik Krimes has gotten me thinking about writing lengths. Although some of my SleuthSayers colleagues will surely disagree, I am convinced that most writers have a favored length or lengths. Lengths in my case. The Anna Peters novels rarely ran more than 240 pages in typescript; my latest straight mystery, Fires of London, was about the same length and with the new, smaller modern type, printed up to 174 pages. My stand alone novels, on the other hand, are in the 350 page range, while my short stories cluster between 12- 17 pages in typescript, with most in the 14-15 page range.

Why this should be so, I have no idea. I just know that beyond a certain length lies the literary equivalent of the Empty Quarter. The Muse has decamped and taken all my ideas with her. As for the very short, I find it intensely frustrating as the required word limit looms when I’ve barely gotten started.

It seems that the big, multi-generation saga, the weighty blockbuster thriller, and the thousand page romance are not to be in my repertory, nor, at the other end of the spectrum, is flash fiction. I’m not alone in this. Ray Bradbury wrote short; Stephen King writes long. Ruth Rendall is on the short side of the ledger, though the novels of her alter ego, Barbara Vine, run at least a hundred pages more. Elizabeth George’s novels started long and are getting steadily longer; the late, under-rated Magdalen Nabb wrote blessedly short, while my two current personal favorites, Fred Vargas and Kate Atkinson, are in the Goldilocks Belt: moderate length and just right.

Classic novels show a similar pattern. Lampedusa’s great The Leopard is short. So is Jane Austen’s work, although most of the other nineteenth century greats favored long. Except for the Christmas Carol, Dickens’ famous novels are all marathons, as are works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and most of the novels by George Eliot and Charlotte Bronte, although the latter’s sister Emily produced the great, and compact, Wuthering Heights.

Would Emily Brontë have gone on to write the triple decker novels beloved of the 19th century book trade? One hopes not, as changing lengths is not always a happy thing for a writer. Dick Francis, whose early mysteries I love, started out writing short and tight. Novels like Flying Finish and Nerve were not much over 200 pages in length. Alas, with fame came the pressures for ‘big novels.’ I doubt I’m the only fan who has found his later work much less appealing.

Other writers have had a happier fate. Both P.D. James and John Le Carre produced short early books then hit their stride with the longer and more complex works that have made their reputations. In a reversal of this trajectory, Stephen King has profitably experimented with some short works on line.

Still, my own experience has been that I do my best work within fairly strict lengths. I’ve tried a couple of times to manage Woman’s World’s 600 word limit. Neither was a happy experience, although I recycled one story and sold it to Sherlock Holmes Magazine – but only after I’d expanded the material to my favored length.

So why am I now appearing in Otto Penzler’s Kwik Krimes, a little volume of 1000 word mysteries, along with 80 other people who are perhaps more in touch with brevity than I am?

The answer lies in Samuel Johnson territory. The good doctor, himself, a working writer who had to grub for every shilling, famously said that “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” However idealistic a writer is and even however unbusinesslike she may be, the Muse leans to Dr. Johnson’s opinion.

There is something about being asked for a story – how often does that happen!– with the promise of a check to follow that lifts the heart. Most writers’ short stories are composed on spec. They emerge from the teeming brain and are sent on their way with a hopeful query, most likely to be returned with a note that they are “not quite right for us at this time.” One can be sure that they will never will be right at some future time, either.

So, a firm request is a great inspiration. I said I’d give it a try, and voila, an idea presented itself. I proceeded to steal an strategy from one of the greats– only borrow from the very best is my motto– and turned out the 1001 words of “The Imperfect Detective.” A thousand words? Close enough.

Why this should be so, I have no idea. I just know that beyond a certain length lies the literary equivalent of the Empty Quarter. The Muse has decamped and taken all my ideas with her. As for the very short, I find it intensely frustrating as the required word limit looms when I’ve barely gotten started.

It seems that the big, multi-generation saga, the weighty blockbuster thriller, and the thousand page romance are not to be in my repertory, nor, at the other end of the spectrum, is flash fiction. I’m not alone in this. Ray Bradbury wrote short; Stephen King writes long. Ruth Rendall is on the short side of the ledger, though the novels of her alter ego, Barbara Vine, run at least a hundred pages more. Elizabeth George’s novels started long and are getting steadily longer; the late, under-rated Magdalen Nabb wrote blessedly short, while my two current personal favorites, Fred Vargas and Kate Atkinson, are in the Goldilocks Belt: moderate length and just right.

Classic novels show a similar pattern. Lampedusa’s great The Leopard is short. So is Jane Austen’s work, although most of the other nineteenth century greats favored long. Except for the Christmas Carol, Dickens’ famous novels are all marathons, as are works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and most of the novels by George Eliot and Charlotte Bronte, although the latter’s sister Emily produced the great, and compact, Wuthering Heights.

Would Emily Brontë have gone on to write the triple decker novels beloved of the 19th century book trade? One hopes not, as changing lengths is not always a happy thing for a writer. Dick Francis, whose early mysteries I love, started out writing short and tight. Novels like Flying Finish and Nerve were not much over 200 pages in length. Alas, with fame came the pressures for ‘big novels.’ I doubt I’m the only fan who has found his later work much less appealing.

Other writers have had a happier fate. Both P.D. James and John Le Carre produced short early books then hit their stride with the longer and more complex works that have made their reputations. In a reversal of this trajectory, Stephen King has profitably experimented with some short works on line.

Still, my own experience has been that I do my best work within fairly strict lengths. I’ve tried a couple of times to manage Woman’s World’s 600 word limit. Neither was a happy experience, although I recycled one story and sold it to Sherlock Holmes Magazine – but only after I’d expanded the material to my favored length.

So why am I now appearing in Otto Penzler’s Kwik Krimes, a little volume of 1000 word mysteries, along with 80 other people who are perhaps more in touch with brevity than I am?

The answer lies in Samuel Johnson territory. The good doctor, himself, a working writer who had to grub for every shilling, famously said that “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” However idealistic a writer is and even however unbusinesslike she may be, the Muse leans to Dr. Johnson’s opinion.

There is something about being asked for a story – how often does that happen!– with the promise of a check to follow that lifts the heart. Most writers’ short stories are composed on spec. They emerge from the teeming brain and are sent on their way with a hopeful query, most likely to be returned with a note that they are “not quite right for us at this time.” One can be sure that they will never will be right at some future time, either.

So, a firm request is a great inspiration. I said I’d give it a try, and voila, an idea presented itself. I proceeded to steal an strategy from one of the greats– only borrow from the very best is my motto– and turned out the 1001 words of “The Imperfect Detective.” A thousand words? Close enough.

31 July 2013

Vacationing with old friends

by Robert Lopresti

My wife and I vacation in Port Townsend, Washington most years, as I have written before (and before). She spends most of the week taking music lessons and I spend mine communing with the muse, or trying to.

But sometimes the best part of a week off is spending time with old friends. That is certainly true of this trip. Not only did I see various music buddies, but I also ran into two writing friends: Elizabeth Ann Scarborough and Clyde Curley.

However, those aren't the friends I want to write about today.

However, those aren't the friends I want to write about today.

I first met Leopold Longshanks almost thirty years ago in a coffeeshop in Montclair, New Jersey. I didn't really meet him there; I just got an inkling that he existed. It took many years for him to solidify into enough of a character to write a story about.

I spent two days on vacation writing a story about Shanks and his wife and had a great time visiting with them. After a dozen tales, they are like old pals and it is great to catch up with them, see what trouble they are getting into.