In choosing a narrative voice most authors historically have opted for the “third person,” which, in many respects, simplifies the writing process since the voice telling the story can be omniscient and removed from the story itself. The author, as a result, does not need to establish a personality for the narrator or worry about what the narrator knows and does not know.

“First person” narration has always had a somewhat larger presence in the mystery genre however, and there is evidence that it may be on its way to becoming the preferred voice there. There certainly are some interesting advantages in telling the story as a personal narrative of a character. Since a character narrator knows only what that character would, in real life, know, use of the first person adds a complexity to the author's task and to the story’s narration. As such, first person narration calls for some creativity and has often been used as a device for narrative experimentation. It is a voice that can invite the author to get a bit sly. Think of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse 5, in which the narrator, while present throughout the story, is not clearly identified as Vonnegut until the firebombing of Dresden when the narrator is standing next to the central character, Billy Pilgrim, and breaks the fourth wall by saying “[t]hat was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.”

“First person” narration has always had a somewhat larger presence in the mystery genre however, and there is evidence that it may be on its way to becoming the preferred voice there. There certainly are some interesting advantages in telling the story as a personal narrative of a character. Since a character narrator knows only what that character would, in real life, know, use of the first person adds a complexity to the author's task and to the story’s narration. As such, first person narration calls for some creativity and has often been used as a device for narrative experimentation. It is a voice that can invite the author to get a bit sly. Think of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse 5, in which the narrator, while present throughout the story, is not clearly identified as Vonnegut until the firebombing of Dresden when the narrator is standing next to the central character, Billy Pilgrim, and breaks the fourth wall by saying “[t]hat was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.”

The classic example of using the first person in a mystery is, of course, the Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle, in which Dr. Watson is the narrator. And the classic example of experimentation with the first person in the mystery genre is Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, narrated by Dr. James Sheppard, who serves as Hercule Poirot’s assistant. While Dr. Watson, assisting Holmes, is very forthcoming, in Christie’s novel we know only what Poirot's assistant, Dr. Sheppard, wants us to know. While he may be close to omniscient vis-a-vis what is going on in the story, we, the readers, are anything but. Dr. Sheppard is, in fact, one of the earliest examples of the "unreliable narrator."

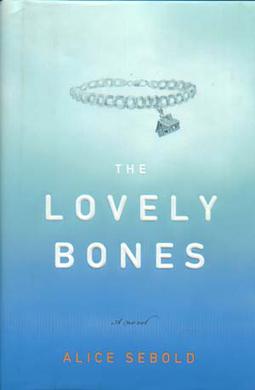

In The Lovely Bones, Alice Sebold tells a haunting story narrated in the first person by the central character, Susie Salmon. Discussing Sebold’s narrative technique requires no spoiler: When the story opens Susie is already dead, the teenage victim of a rape murder. She narrates the story from heaven -- a first person narrative that grants the narrator the omniscience Susie gains from her perspective in heaven, where she grapples with her family’s grief, her own demise, and the quest of everyone to bring down the monster responsible. Little Brown and Company agreed to publish Sebold’s 2002 novel even though their view was that given the premise of the book they would be lucky to sell 20,000 copies. In fact, The Lovely Bones sold well over one million copies and was on The New York Times bestseller list for over a year. Susie's circumstances, so steeped in sorrow and horror, have caused many (my wife, included) to not give the book a try. But I strongly commend it to you. Read it and watch the catharsis that Sebold weaves amidst the sorrow, and watch how she uses Susie’s first person narration to pull it off.

Alice LaPlante’s debut novel Turn of Mind in fact turns any idea of omniscient first person narrative on its head. The central character and first person narrator in Turn of Mind, Dr. Jennifer White, is an Orthopedic surgeon suffering from Alzheimer's disease. She is not our typical unreliable narrator. Rather than holding things back from the reader, here there are simply things that occurred previously that Dr. White, our narrator, no longer remembers. As readers we are imprisoned in her mind, a mind that Dr. White herself describes as:

This half state. Life in the shadows. As the neurofibrillary tangles proliferate, as the neuritic plaques harden, as synapses cease to fire and my mind rots out, I remain aware. An unanesthetized patient.

And, as readers, that is our state as well. Dr. White may or may not have killed her friend and neighbor from down the street. Unlike Dr. Sheppard in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Dr. White holds back no information. But, unlike Susie in The Lovely Bones, she is no where close to omniscient. She, and we, have no idea whether she was involved in her friend’s murder. LaPlante uses this constricted first person narrative to deliver a taut thriller built on a growing fear and paranoia on the part of the narrator as, before our very eyes, she declines into dementia.

Another recent debut novel displays yet another example of a constrained first person narrative. In Before I Go to Sleep, by S. J. Watson, the central character and narrator, Christine Lucas, is a 47 year old woman suffering from a rare but recognized disease -- anterograde amnesia. She awakens every morning with no memory of her previous life. She, in effect, has to re-learn who she is anew every day. The thriller therefore progresses with the reader closer to omniscience than the narrator -- we know all that Christine has discovered in previous days, which, each successive morning, is more than Christine herself knows. John O’Connor, writing in The Guardian says this about S.J. Watson's narrative choice: “The structure is so dazzling it almost distracts you from the quality of the writing. No question, this is a very literary thriller.”

And, finally, let’s end with a more subtle experimentation in first person narrative. In Laura Lippman’s The Most Dangerous Thing all of the flashback chapters, chronicling underlying events that transpired when the central characters in the story were children, are written in the first person. As mystery fans, when you read this book you will doubtless attempt (as did I) to figure out precisely which one of those characters is the unnamed and unidentified narrator of the flashbacks. But if you investigate carefully you will find that for various reasons every single one of the characters can be eliminated -- there is no one in the book who individually could supply the first person narration in the flashback chapters. Lippman hints at what is going on when, in several passages, she refers to the children as having been so close that they were like appendages of a single creature. The strange but inescapable conclusion, then, is that the narrator of these chapters (like the collective narrator in Jeffrey Eugenides The Virgin Suicides) is the entire group, speaking to the reader in first person plural. In an interview following publication of her book Ms. Lippman has confirmed this conclusion and explained her decision to use first person plural narration as follows:

The decision was intuitive at first—that is, I knew it was right, without knowing why it was right. When I finished the book, I realized that these passages are a consensual version of what happened in the past, that the survivors have agreed on what happened and that’s why the story is, at turns, unflattering to each of them. They are working out their level of culpability in several tragedies and they just can’t face this alone. And that voice allowed me to include a subtext of gloom and foreboding—the story is being told by people who know how badly it ends.

All of which goes to show that the choice of narrative voice has a direct effect on how the story is told. The advantages of opting to tell your story in the first person also can mirror the disadvantages. Following a more standard third person narrative approach gives the writer the relatively easy task of telling his or her story from the perspective of omniscience. The narrator need not be given personal characteristics and the author can expect the reader to accept the narration as gospel.

By contrast, the first person narrator is a character that the author must bring to life and then employ consistently. The narrator must speak -- throughout the entire story -- as that character would, and must act with consistency as that carrier also would given his or her background. And particularly in the mystery genre, we have all (thank you, Agatha Christie) been taught to expect the unreliable narrator. The reader may not trust your narrator, or even like him or her very much. But, as the works discussed above illustrate, writing within the constraints imposed by telling the story through the eyes of a first person narrator can spark an author's creativity and can be exhilarating and fun, both for the writer and for the reader.

By contrast, the first person narrator is a character that the author must bring to life and then employ consistently. The narrator must speak -- throughout the entire story -- as that character would, and must act with consistency as that carrier also would given his or her background. And particularly in the mystery genre, we have all (thank you, Agatha Christie) been taught to expect the unreliable narrator. The reader may not trust your narrator, or even like him or her very much. But, as the works discussed above illustrate, writing within the constraints imposed by telling the story through the eyes of a first person narrator can spark an author's creativity and can be exhilarating and fun, both for the writer and for the reader.

Dale, I’m sold on those books, particularly the first three. Thanks for bringing them to our attention.

ReplyDeleteI think I’ve seen a crime thriller some time in the past in which the central character has anterograde amnesia. As I recall, he wrote notes on his arm so he could ‘remember’ what he needed to know.

When it comes to 1st v 3rd person, I believe in the right tool for the job. I’ve seen first person misused, but done write, it offers a personal glimpse.

I rememvber in the ieghth grade reading A SEPERATE PEACE and being stunned when the teacher made a case for the unreliable narrator, although he didn't use that phrase. He argued that it was much more likely (by simple physics) that Phinney had shaken the branch then that the narrator had done it. It had never occurred to me that there could be another explanation for a book...

ReplyDeleteUnreliable narrators are all over history. Diaries are fascinating, but you cannot trust them: even Samuel Pepys didn't include ALL his philandering, and the Duc de St. Simon's presentation of political machinations that make 2013 look like kindergarten is cupped in his own moral rectitude. Memoirs and biographies are full of personal bias - for an example, read Trotsky's bio of Stalin, or whoever wrote the bio of Richard III which has been attributed to Thomas More. Personally, I assume any narrative is somewhat unreliable (it's the historian in me, or is it the pessimist? - humans are humans). But I kind of like that. It allows me to bring my own analysis to the game.

ReplyDeleteI agree that biographies (particularly auto, that is, the first person ones) are notoriously unreliable. As Benjamin Franklin wrote in his, "I dress differently for public than for private."

ReplyDeleteGood post, Dale. I have three quibbles (or addenda). One, nowadays a third-person novel with an omniscient narrator is the exception; the rule is "close third person," in which it's almost as important to tell only what the protagonist knows as in first person. Two, there are quite a number of wonderful unreliable-narrator mysteries. The catch is (and I've thought about this a lot) that if you say the narrator of a book is unreliable, it's already a spoiler and will ruin the impact on the reader you've told who hasn't already read it.

ReplyDeleteThree, anterograde amnesia isn't rare. It's the main symptom for Korsakoff syndrome (what used to be called "wet brain" colloquially), which is common among alcoholics (1 in 8 according to one source). The similar dementia in Alzheimer's patients is also a form of anterograde amnesia. It's as if the "record" button is broken in the affected person's mind, so any new experience is forgotten immediately.

Thanks for a thoughtful defense of the first person point of view, which I've actually read described as a primitive or simplistic form of storytelling, a stage a writer goes through on the way to more serious work. You've shown that first person can be pretty complex. Plus, you've added to my vacation reading list.

ReplyDeleteI take Elizabeth's point about "spoilers" and the fact that identifying an "unreliable narrator" gives away the trick. I think Christie's use of the technique in Ackroyd is so well known that referring to it as such probably gives away nothing more than that which is already common knowledge among mystery buffs. I think the context of the narrative discussion vis-a-vis the other books in the post gives away nothing. The only possible exception to this, I think, is Gone Girl, but (again) the discussion of the narrative device there by the author herself is really wide-spread. And Terry -- these books are some of my favorites! By all means pack them for a vacation. One of the reasons I dealt with all of the books in one post is so as to highlight them without giving away too much of their plot. I HATE the normal book review process where the reviewer reveals 80% of the author's tricks before you have even opened the book!

ReplyDeleteI'll blow the horn here for Robert Bloch's story "Yours Truly Jack The Ripper," a clever use of first person narration.

ReplyDelete