We've played this game three times before. Below you will find

ten familiar figures from popular culture. But where did they start

their careers? In many cases you may know the answer, but they will turn

out to be more complicated than you expect.

We've played this game three times before. Below you will find

ten familiar figures from popular culture. But where did they start

their careers? In many cases you may know the answer, but they will turn

out to be more complicated than you expect.

See the white box on the side? Your choices lie within.

Frankie and Johnny

Little Orphan Annie

Lassie

Frank Furillo

Humpty Dumpty

Columbo

Peter Pan

Jimmy Valentine

Maynard G. Krebs

Gilgamesh

And here are the answers:

Frankie and Johnny. Real life. The classic murder ballad was inspired by the real killing of Allen (Albert) Britt by his sweetheart Frankie Baker in St. Louis, in 1899. She shot him after finding him with a prostitute but was found not guilty, pleading self-defense. Bill Dooley wrote a song called "Frankie Killed Albert." In 1912 Bert and Frank Leighton revised that to "Frankie and Johnny" and Albert has gone by that name ever since. It has been recorded too many times to count.

|

| Mary Alice Smith |

Little Orphan Annie. Comic Strip. Harold Gray created the comic strip in 1924. It ran until 2010, spawning a Broadway musical and a bunch of movies. But the name, or a variation thereof, is even older. James Whitcomb Riley wrote a poem in 1885 called "The Elf Child." In later editions he changed the title to "Little Orphant Allie" but a typesetter thought otherwise and the protagonist has been Annie ever since.

The poem is about a young orphan who comes to live with a family and tells the children scary stories that encourage good behavior. "The goblins will get you if you don't watch out."

Riley based the poem on Mary Alice Smith, who lived with his family growing up. So the real little Allie inspired the poem which led to the comic strip. Got it?

Lassie. Short story. Ah, but which one? British author Elizabeth Gaskell wrote "The Half-Brothers" in 1859 in which a female collie leads a search party to two boys lost in the snow. Sound familiar?

But in 1938 Eric Knight wrote a story called "Lassie Come-Home" about a doggie making a long journey to her master. This led to a novel of the same name. Several movies followed, followed by a radio show, and finally the TV series many of us remember. Dave Barry complained that the family in that show spent so much time trapped in wells that they only survived on federal farm subsidies, and Lassie had to fill out the applications.

Frank Furillo. Television. But you can get a good argument going about it. Lieutenant Furillo was the protagonist of the classic series Hill Street Blues. But some people claimed the show was, let's say, heavily indebted to Ed McBain's 87th Precinct novels, which starred a cop named Carella.

I don't see it myself. McBain's books are all about a detective squad while the series covered all levels of a precinct.

What did McBain himself think? In his novel Lightning he has a character furiously argue that the show is based on the lives of him and some of his associates. But in a brilliant bit of fourth-wall-bending, the author manages to have his cake and eat it too.

You see, the complainer is Fat Ollie Weeks, a bigoted cop and hardly the first person whose opinion you would trust. So is McBain mocking the theory of the connection?

Not quite. Steve Carella, definitely a reliable voice, is skeptical about Ollie's view but he says that saying the name Ollie Weeks is like (TV character) Charlie Weeks is similar to claiming that the name (TV character) Howard Hunter is like Evan Hunter.

Evan Hunter is Ed McBain's real name. And Hunter/McBain thought about suing the producers, but decided it was too expenaive.

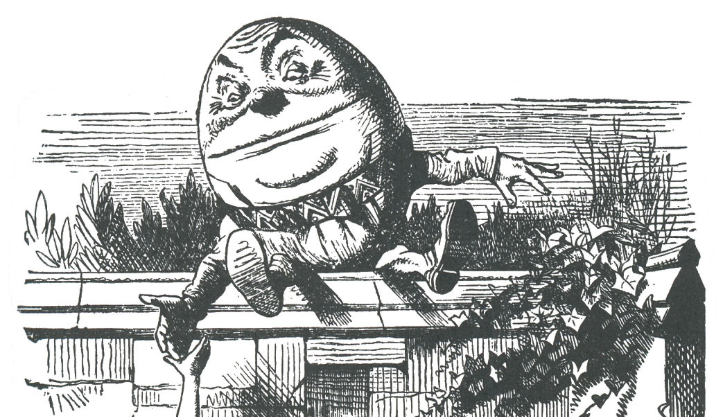

Humpty Dumpty. Nursery rhyme. I have run into people who think ol' H.D. started life in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass. He first appeared a century earlier, 1791, in a nursery rhyme. John Tenniel in Looking Glass gave him his familiar appearance. while Carroll, gave him his the obnoxious personality many of us remember:

"When I use a word," Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, "it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less."

"The question is," said Alice, "whether you can make words mean so many different things."

"The question is," said Humpty Dumpty, "which is to be master—that's all."

That argument has been quoted by judges in more than 200 legal decisions.

By the way, it is generally agreed that the nursery rhyme was meant to be a riddle. It was identified as such by at least 1843. It is easy to forget that it is a riddle because we all know the answer so well. In the same way, the surprise twist of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has not surprised anyone in a very long time

Columbo. Television. But much earlier

than you might think. Richard Levinson and William Link wrote "Enough

Rope," which in 1960 appeared as an episode of The Chevy Mystery Show. It included Bert Freed as the famously inquisitive cop.

In 1962 L&L turned their TV episode into a play, Prescription: Murder. In 1968 the story that wouldn't die was turned into a TV movie. But who would play the hero? Lee J. Cobb was not available. Bing Crosby (!) was considered but he thought it sounded like too much work. Then came Peter Falk who said he would kill to play the part. If he had, I'm sure Columbo would have caught him.

The show was a huge hit, of course, and the show went onto a long but irregular career: There were almost 70 episodes, spread out over more than 30 years.

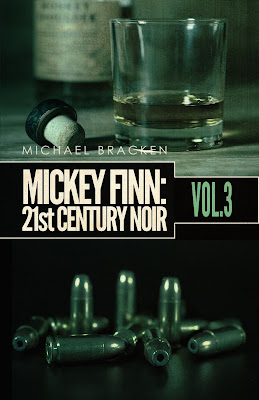

Oh, one more detail: Remember I said Columbo began on TV? Technically true, but back in 1960 Levinson and Link published a story in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine called "Dear Corpus Delecti." Their original title was "May I Come In?" which should give you a hint about one of the characters. But the police lieutenant in this story was named Fisher.

And speaking of names, What was Columbo's given moniker? It is never mentioned in the show but sharp-eyed viewers noticed that his police ID said it was Frank.

Not surprising that no one called him by his first name. The man, especially in early years, was practically a phantom. I theorized that he wasn't a cop at all but a nut who had gotten his hands on a badge. I mean, in the first episodes we never saw him in a police station and he had to introduce himself to every police officer he encountered...

Peter Pan. Novel. The Little White Bird is an adult novel by J.M. Barrie (1902) about an aging bachelor trying to establish a relationship with a young boy. I hasten to add that "adult novel" only means that it was not aimed at children. Let's not take this the wrong way.

In the middle of the book Barrie wrote an odd section about a week-old baby who travels to Kensington Gardens where he is taught to fly by fairies and birds. This baby's name is... Frank Columbo.

Sorry. Got my notes mixed up. It was Peter Pan. Two years later Barrie returned to the character with the play Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up, which brought in Wendy, the lost boys, Neverland, Captain Hook, etc. Then there was a novel, and who can keep up with all the variations that followed...

Jimmy Valentine. Short story. The most famous safecracker in fiction is sort of like Professor Moriarty, in that he has taken on a much larger life than his creator ever dreamed or intended. O. Henry wrote precisely one tale about Valentine, "A Retrieved Reformation," but it is such a classic that it has led to five movies and a radio show. Stick to the short story; it's a treat.

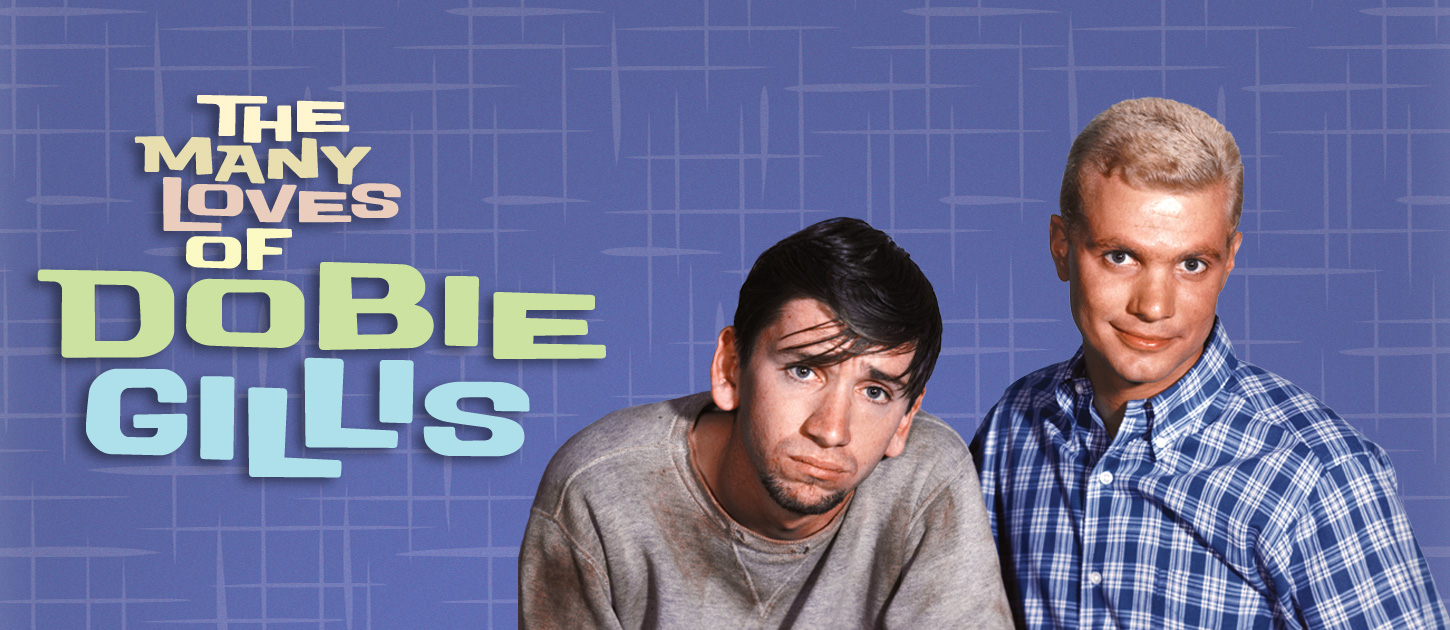

Maynard G. Krebs. TV. The lovable beatnik, played by Bob Denver, who shrieked in horror at the sound of the word "work," appeared on the TV series The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, which was based on the novel of the same name by Max Shulman. Maynard, however, does not appear in the novel. He is a creation of the scriptwriters and is probably television's first example of a breakout character, paving the way for Fonzie and Steve Urkel, among many others.

Gilgamesh. Real life? Now, hear me out. Certainly Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, slayer of monsters, and seeker after immortality, was the legendary protagonist of an epic poem, one of the oldest surviving works of literature . But once again, it's more complicated than that. What follows is from David Damrosch's excellent The Buried Book.

We have a list of the kings of the Sumerian region. The recent (and by "recent" I mean about 3,000 years old) kings are recorded to have ruled for reasonable lengths of time, say six to thirty years. But the oldest kings supposedly ruled for hundreds of years.

Unless you believe those early monarchs had a really fabulous health care system, we can assume that they are mythical, or no more than names the chroniclers dutifully recorded.

Now guess who stands squarely between the mythical old and the realistic new? Gilgamesh, supposedly ruling for 126 years. Which suggests to many scholars that he was the first king for whom they had authentic records. But I doubt he really slayed the bull of heaven. That sounds like p.r.

Interestingly, the Epic of Gilgamesh vanished from the record for two millennium until 1872 when George Smith, an engraver and self-taught amateur scholar, translated the cuneiform tablets in the British Museum. Victorian England was shocked that the epic included the story of a world flood which only one man's family survived - and the man's name was not Noah.

And that's enough. As Little Orphan Annie probably never said, see you in the funny papers.