Please not yet. Those are the three eternal words. Please not yet.

John D. MacDonald

A Deadly Shade of Gold

As usual the month of February finds me on the gulf shore of Alabama, making a good on a promise my wife and I made to ourselves back when we were still in the work-a-day world: once we retired February would never again find us in Washington, D.C. So we have again traveled south to a rental on the shore. Not the tropics, but also not the frozen east coast of the past several weeks.

| Harper Lee |

Whether we should feel some trepidation as we await the return of Atticus and Scout in the long-withheld Go Set a Watchman has already been the subject of numerous articles. Far be it from me to add another. But aside from such speculations concerning the ultimate merit of the Mockingbird sequel, an interesting sidelight to the pending publication of Harper Lee’s second novel is the reaction of the reading public, which had become resigned to Lee’s oft-articulated position that she would never publish a second work. This had been both accepted and hard to get over -- we had fallen in love with Mockingbird -- and Lee’s resolve to leave it at that had left us feeling a bit like a child allowed but one toy. The anticipation has been overwhelming with the possibility of another now on the horizon.

|

| Arthur Conan Doyle |

But what happens when the series ends for reasons beyond the author’s ability to remedy; when the author is gone but nothing is left behind? Since, as noted, I am gazing out toward the Gulf as I type, what could be more natural than to allow my gaze to linger off toward the east, where 17 miles away Florida beckons? And what is more “Florida” than John D. MacDonald and his iconic literary sidekick Travis McGee?

|

| John D. MacDonald |

This man whom I'd snobbishly dismissed as a paperback writer turned out to be a novelist of the highest professionalism and a social critic armed with vigorous opinions stingingly expressed. His prose had energy, wit and bite, his plots were humdingers, his characters talked like real people, and his knowledge of the contemporary world was -- no other word will do -- breathtaking.

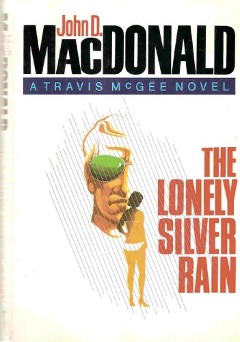

This is not the first time that I have offered up thoughts on MacDonald and McGee in this space. Unlike Harper Lee, who wrote but one book (now, two), John D. MacDonald (like Doyle) was prolific. He wrote almost 80 works of fiction and nonfiction, and 21 McGee novels before his sudden death in 1986. But he still left us hanging. In the last of the Travis McGee series, The Lonely Silver Rain, McGee is confronted with several revelations (no further spoilers here!) but then, given MacDonald’s demise two years later, McGee’s fans are ultimately left to ponder where these revelations might have led.

Like Harper Lee, whose sequel to Mockingbird was known by some friends to have existed, at least at one time, MacDonald, too, was rumored to have a final Travis McGee novel under lock and key. I remember reading as much in a 1975 interview with MacDonald, and Stephen King has stated that before MacDonald's death he had discussed with King the backbone of what would be the final McGee adventure. But all rumors of that final work, usually conjectured to bear the title A Black Border for McGee, were apparently baseless. MacDonald’s heirs have asserted that no such work exists, and have steadfastly refused all requests by other authors -- most notably one from Stephen King -- to continue (and properly end) the series. One caveat, here: there is a little-known novel, The Black Squall, by Lori Stone, which sneaks around the heirs' prohibition by offering a final adventure clearly addressing what might have happened to Travis McGee and his friend Meyer, but doing so without ever using their actual names. But other than that, barring a Harper Lee, or Arthur Conan Doyle-like denouement -- a final work miraculously discovered -- that is it for McGee.

Like Harper Lee, whose sequel to Mockingbird was known by some friends to have existed, at least at one time, MacDonald, too, was rumored to have a final Travis McGee novel under lock and key. I remember reading as much in a 1975 interview with MacDonald, and Stephen King has stated that before MacDonald's death he had discussed with King the backbone of what would be the final McGee adventure. But all rumors of that final work, usually conjectured to bear the title A Black Border for McGee, were apparently baseless. MacDonald’s heirs have asserted that no such work exists, and have steadfastly refused all requests by other authors -- most notably one from Stephen King -- to continue (and properly end) the series. One caveat, here: there is a little-known novel, The Black Squall, by Lori Stone, which sneaks around the heirs' prohibition by offering a final adventure clearly addressing what might have happened to Travis McGee and his friend Meyer, but doing so without ever using their actual names. But other than that, barring a Harper Lee, or Arthur Conan Doyle-like denouement -- a final work miraculously discovered -- that is it for McGee.

So aside from The Black Squall (which, I admit, I have not read) the many fans of Travis McGee have had to look elsewhere over the last thirty years for a fix. And that has sparked a bit of a literary cottage industry among authors seeking to re-capture, and then offer to the reading public, the essence of McGee.

So, pause with me here. What, at base, is the Travis McGee formula? What do readers look for in a Travis McGee novel? The series evolved over time, but viewed in its entirety it seems to me MacDonald's McGee adventures are comprised of the following base elements:

| The Busted Flush, as imagined |

Second, there is the “best friend” buddy who provides an intellectual counterpoint, someone with whom the protagonist can spar during the course of the narrative. This companion must be colorful in his own right, intelligent, and equally detached, but must in some respects stand in independent contrast to the protagonist. McGee’s “buddy” is Meyer, an erstwhile economist, who lives on his nearby book-packed ship, initially The John Maynard Keynes, later (after The Keynes fails to survive an adventure) The Thorstein Veblen.

Third, the stories, at their heart, focus on the strengths, and the largely man-made weaknesses, of the state of Florida. Even when they do not take place there, each Travis McGee adventure displays a love of the natural Florida ecosystems, a disgruntled horror as to what is happening to them, and a matching disdain for those who are “developing” the state out of existence. A kind word is never said about a double wide, a condominium, a jet ski or a Hawaiian shirt. As Florida author Carl Hiassen has written: "Most readers loved MacDonald's work because he told a rip-roaring yarn. I loved it because he was the first modern writer to nail Florida dead-center, to capture all its languid sleaze, racy sense of promise, and breath-grabbing beauty."

Fourth, the adventures must be well written. MacDonald often criticized what he viewed as "hack" writing, and his own works set a high bar with his clean and spare prose, his eye for detail, and his ear for dialog.

With these elements in mind, for those craving a Florida fix, or, more specifically, a Travis McGee fix, there are at least two series that work pretty hard to deliver: The Doc Ford series written by Randy Wayne White, and the Thorn series written by James W. Hall.

Doc Ford, a retired NSA agent and marine biologist, has been the hero of 21 mysteries written by Randy Lee White, with a 22nd, Cuba Straits, due out this March. The similarities to the McGee stories are striking. Ford is decidedly “off the grid,” living in a stilt house above the water on the gulf coast of Florida and ostensibly making his living by peddling marine specimens to collectors and scientists. His best friend and sidekick (like Meyer, always referred to by a single name) is Tomlinson, a frequently stoned philosopher who lives nearby on a Morgan sailboat (also, in a direct nod to MacDonald, named The Thorstein Veblen). And the Doc Ford stories invariably contain impassioned takes on the delicate Florida eco structure and the angry rants of a frustrated environmentalist protagonist as he witnesses what is happening to it.

Another take on the formula is James W. Hall’s series, featuring the loner Thorn. Thorn is also an environmentally-aware protagonist who lives in a Florida shack built above the water and makes his living tying fishing lures. He is an orphan and a maverick, and is usually aided by his (again, one-name) sidekick Sugarman, a Florida policeman (and, eventually, ex-policeman) who serves as Thorn's verbal sparring partner as they fight various injustices, including the abuses rendered to the Floridian land and sea.

Each of these series has its faithful followers, and each is well written. Randy Wayne White has authored over fifty books, fiction and non-fiction, under his own name and several aliases. James W. Hall is both a novelist and an accomplished poet. The reader expects well written prose from these gentlemen and the authors deliver. But having read most of White’s series and the first third of Hall’s, there is still something missing for a reader, such as myself, in search of Travis McGee. Maybe it is the fact that Doc Ford, and (I suspect) Randy Wayne White, at least for me, is a little too right wing for a steady diet. Maybe it’s the fact that entirely too many of the characters in Hall’s series end up dying, and in gratuitous ways unnecessary to the logical progression of the story.

But lets face it: criticism is easy. And, by the same token, concocting a riveting tale and telling the tale as well as MacDonald, by contrast, is hard. It takes a real hand to pull off a Florida series that can be read as a steady diet. I can’t even do that with Carl Hiaasen's novels. When I have read a few I feel the need to come up for air. These books, and other Florida capers, are fine as far as they go, but they still pale when compared to the works of John D. MacDonald, in the words of Stephen King “the great entertainer of our age, and a mesmerizing storyteller.”

|

| The last Travis McGee novel |

For fans of these authors it is not so much how many books were written as it is facing the prospect that there will be no more. It is that prospect that leaves us overjoyed at the unexpected promise of Go Set a Watchman or that final Sherlock Holmes story, and despairing over the fact that McGee's tale is apparently done. The response of many of us to the fact that it is all over is a rift on McDonald’s three eternal words:

“Please, not yet.”

.jpg)