|

| Janet Hutchings photo by Laurie Pachter |

Yesterday we began a series of interviews with the editors of the Dell mystery magazines. We began with Jackie Sherbow, we finish tomorrow with Linda Landrigan. But today we welcome Janet Hutchings.

— Robert Lopresti

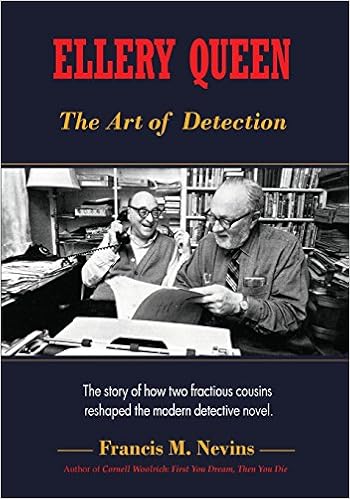

Janet Hutchings has been the editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine since 1991. She is a co-winner of

the Mystery Writers of America’s Ellery Queen Award and the Malice Domestic Convention’s Poirot Award, and in 2003 she was honored by the Bouchercon World Mystery Convention for contributions to the field. Under her editorship, EQMM was named Best Magazine/Review

Publication by Bouchercon 27 and in 2017 was celebrated by Bouchercon 48 for Distinguished Contribution to the Genre.

- Relate a piece of history about your magazine.

- EQMM made history with its very first issue. When founding editor Fred Dannay released the magazine to the world in the fall of 1941 he was offering readers an entirely new type of publication. He’d decided to bring together between the covers of a single magazine stories of such widely different sorts that the combination would create a new type of audience for the mystery short story. Everything from what he called realistic stories of the hardboiled school to classical whodunits in the style of England’s Golden Age of mystery to stories no one would even remotely have considered mysteries before, by mainstream and even literary writers, were to be included. It was all, he said, “frankly experimental.”

Previously there had been the pulps, focused on hardboiled action-based stories, and the slicks, which published about one mystery per issue of a more traditional kind, but there was no single publication for readers who liked both forms—or for those who liked an even wider mix of stories. EQMM’s first issue sold more than 90,000 copies and the magazine soon began to exert an influence not only upon mystery fiction—helping to define the boundaries of the genre as we know it today—but upon the wider culture. At least one recent contemporary scholar has argued that EQMM was one of the many forces that influenced the postmodernist movement in the arts and literature. Modernism had made a clear distinction between art (or what we might call “high art”) and popular culture. Postmodernism rejected that distinction. But rejecting that divide was exactly what Dannay was doing in the early days of EQMM, mixing the high brow and the popular—the “literary” and the genre story. - What is one thing you wish everyone would know about your publication?

- One thing I wish everyone would know not just about EQMM but about short-story magazines in general is that they are not just agglomerations of stories. In recent years various e-publishers and websites have been making individual stories available for sale or for free reading. But what the reader gets by subscribing to a short-story magazine is not simply a collection of individual stories, it is—or should be—a more complex reading experience.

The magazine should be designed to take the reader on a journey, via the juxtaposition of the stories, sometimes also by thematic convergences, and sometimes by means of commentary that may accompany a given story (the most famous example of the latter being Fred Dannay’s lengthy introductory essays for so many of the stories in early EQMMs). A short-story magazine should also seek to broaden readers’ tastes by offering, occasionally, something the readership would not necessarily be expected to like. I hope short-story magazines are never replaced entirely by short stories sold individually, because if that happens, a place in which discovery can occur will be lost. It’s an editor’s job to stretch readers’ horizons. - What does a typical workday for you look like?

There’s no typical day. I’m a little obsessive about keeping up with reading. When I hold a story for more than two or three weeks it’s usually either because something special is going on or because I like the story and hope eventually to find a space for it. Whenever possible, I devote one day a week entirely to reading. In recent months, social media has also been taking up a lot of my time: we now blog, podcast, and post on Twitter and Instagram—in between our primary duties, which are curating, editing, and finalizing each issue for the printer.- Have you always been a fan of mysteries?

- I always read and enjoyed mysteries, from childhood on, but I was not a really dedicated fan until I got a job at the Mystery Guild in the 1980s. We got to read virtually every mystery novel that was published in a given year there, and it was so much fun! Still publishing some of the authors I first read there—such as Simon Brett.

- Aside from short mystery fiction, what other parts of the genre do you enjoy?

I’ve had very little opportunity in recent years (with eyes always tired from reading submissions) to keep up with what’s going on at novel length in the field; nevertheless, I don’t feel out of touch with the genre as a whole. I once wrote that from our small outpost as editors of short-story magazines, we get to see the whole of the broad, fascinating universe of mystery and crime fiction.

I don’t consider the mystery short story to be a single form. It is, it seems to me, a multiplicity of forms in terms of length, and also a multiplicity in terms of structure. There’s everything from the miniature novels that Ed Hoch wrote for EQMM for so many years to the circularly structured twist-in-the-tail story (and much in between). I call the twist story “circular” because when you get to that final twist you see that it is what the whole story had to be leading up to. Flash fiction is another separate form, and in its compression it often has to convey whatever is necessary to the story through imagery; it says a lot in a very few words and in this it can sometimes have a lot in common with poetry. There’s so much more that falls under the mystery short story umbrella than I can mention here.- What great short story or collection have you read recently?

- I am currently reading Joyce Carol Oates’s new collection Night-Gaunts and Other Tales of Suspense. I’ve been a fan of Joyce’s work for decades—long before I came to EQMM!

- What is your personal editorial philosophy?

- This isn’t easy to characterize succinctly. First, although I sometimes offer thoughts about how I think a story might be improved, I see my job as editor as fundamentally different from that of a critic or a teacher. My first responsibility as editor is to our readers. I read as a sort of proxy for them. And reading for them means I have to try to read in the way that they will read the finished magazine—for enjoyment, in other words, and not critically. When I sit down to read submissions, what I’m hoping for, no matter what the subgenre of the story, is to be taken out of my own life and all that surrounds me and be pulled entirely into the world of the story. I like all types of mysteries—indeed, all types of stories. Genre is not very important to me. A story will generally succeed or fail for me depending on how deeply the author is able to immerse me in it. And it isn’t always the best-crafted story that succeeds in doing this. It’s often the inexperienced Department of First Stories author who holds me captive from first page to last. I think this has something to do with passion (perhaps before writing becomes a job) or with the fact that first efforts often draw deeply from experience that has profoundly affected the author.

- When I do attempt to give advice, I try to approach each short story as an organic whole. I know a lot of writers and also teachers of creative writing put a lot of emphasis on the importance of the separate parts of a story. The opening line is something that seems to be given a lot of weight. I often hear writers advised that they need an “attention grabbing” opening line. I think too much emphasis is put on this. A great opening line may be vital to a writer in getting the creative juices flowing. Some writers have told me they have to have an attention-getting opening line as the seed for the story. That’s fine. But from a reader/editor’s perspective what makes the opening line good or bad is how it serves everything that follows it in the story. Endings, it seems to me, are harder. I think an ending should have a sense of inevitability that derives from all that goes before it. But again, it’s the story as a whole—the particular story—that is my focus, not any rules I could formulate.

- What do you love about short stories?

- The tightness of the structure, and the fact that they can be read in one sitting. As Edgar Allan Poe pointed out, what you can read in a single sitting has the potential to have a profound impact. Life does not intervene.

- What’s a place you’ve traveled to that has stuck with you, and why?

- I lived in England for most of my twenties, and since those are formative years, I’m sure the affinity I have for most things British will never leave me. It’s wonderful having so many British writers contributing to EQMM, though that was none of my doing; it must be credited to my predecessor, Eleanor Sullivan. In geographical terms, EQMM’s reach has always been wide. From the earliest days, the magazine has looked for the best in mystery and crime stories from all over the world. There were 13 international contests run in the early years of the magazine and they received submissions from nearly two dozen countries.

One of my favorite departments is Passport to Crime, which we launched in 2003 with a crime story per month in translation. I’m not much of a traveler these days, but two trips I’ll never forget were the Soviet Union in the 1970s—it was like waking up in a war movie from the 1940s, with rationing and not much color and no advertising— and Costa Rica a couple of decades later, where I spent a night in a rain forest in a storm, with the animals seeming to generate as much noise as a NYC street. These days, I let our Passport authors take me where I want to go. - Where did you grow up?

- The Chicago area, “flyover country.” Which is funny because I was once accused by an author whose work wasn’t accepted to the magazine of being an insular New Yorker with no understanding of the Midwest. I love my adopted city and state, but the Midwest will always be a part of me.

Thanks, SleuthSayers, for hosting the Dell Mystery Magazines editors! Tomorrow, Linda Landrigan.