Again, first off, a disclaimer. This is not a political rant any more than my previous post. Last time, I went after Michael Flynn for his lack of deportment. This time, I'm inviting you into the Twilight Zone.

We have a habit, in this country, of thinking we're the center of attention. In other words, Trump's issues with his Russian connections are all about American domestic politics. There's another way to look at this. What if it turns out to be about Russian domestic politics?

Bear with me. Filling in the background, we have Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. This appears not to be in dispute. There's a consensus in the intelligence community. Fairly obviously, Hillary Clinton wasn't the Russians' first choice, and she seems to have inspired Vladmir Putin's personal animus. It's not clear whether the Russians wanted simply to weaken Clinton's credibility and present her with an uncertain victory or if they thought they could engineer her actual defeat.

Deception and disinformation are tools of long standing. Everybody uses them, and the Russians have a lot of practice. They've in fact just announced the roll-out of a new integrated platform for Information Warfare, and under military authority (not, interestingly, the successor agencies to KGB). Their continuing success in controlling the narrative on the ground in both Ukraine and Syria, less so in the Caucasus, demonstrates a fairly sophisticated skill-set. To some degree, it relies on critical mass, repeating the same lies or half-truths until they crowd out the facts. Even if they don't, the facts become suspect.

Now, since the Inauguration, we've had a steady erosion of the established narrative. Beginning with Gen. Flynn, then Sessions, former adviser Page Carter, Jared Kushner. Consider the timeline. Nobody can get out in front of the story, because the hits just keep coming. They're being blind-sided. "They did make love to this employment," Hamlet says, and none of them seem to realize they could be fall guys, or that it's not about them.

The most basic question a good lawyer can ask is cui bono. Who benefits? If the object was to have a White House friendlier to the Kremlin than the one before, that doesn't appear to be working out. But perhaps the idea is simply to have an administration in disarray, one that can't cohesively and coherently address problems in NATO, say, or the Pacific Rim. Short-term gain. Maybe more.

Let's suppose somebody is playing a longer game. We have a story out of Russia about the recent arrests of the director of the Center for Information Security, a division of the Federal Security Service, and the senior computer incident investigator at the Kaspersky Lab, a private company believed to be under FSB discipline - both of them for espionage, accused of being American assets, but both of them could just as plausibly be involved in the U.S. election hack. What to make of it? Loose ends, possibly. Circling the wagons. Half a dozen people have dropped dead or dropped out of sight lately, former security service personnel, a couple of diplomats. Russians have always been conspiracy-minded, and it's catching. You can't help but think the body count's a little too convenient, or sort of a collective memory loss.

Here's my thought. This slow leakage and loss of traction, the outing of Flynn and Sessions and the others - and waiting for more shoes to drop - why do we necessarily imagine this has to come from the inside? Old rivalries in the intelligence community, or Spec Ops, lifer spooks who didn't like Mike Flynn then and resented his being booked for a return engagement later. Just because you want to believe a story badly doesn't make it false. But how about this, what if the leaks are coming from Russian sources?

Remove yourself from the equation. It's not about kneecapping Trump, it's about getting rid of Putin, and Trump is collateral damage. There are factions in Russia that think Putin has gotten too big for his britches. He's set himself up as the reincarnation of Stalin. And not some new Stalin, either. The old Stalin. None of these guys are reformers, mind you, they're siloviki, predators. They just want to get close enough with the knives, and this is protective coloration. Putin, no dummy he, is apparently eliminating collaborators and witnesses at home, but somebody else is working the other side of the board.

If the new administration comes near collapse, because too many close Trump associates are tarred with the Russian brush, the strategy's going to backfire, and the pendulum will swing the other way. The scenario then has the opposite effect of what was intended. Putin will have overreached himself, embarrassed Russia, and jeopardized their national security. That's the way I'd play it, if it were me, but I'm not the one planning a coup.

This is of course utterly far-fetched, and I'm an obvious paranoid. Oh, there's someone at the door. Must be my new Bulgarian pal, the umbrella salesman.

08 March 2017

The Ghost in the Machine

Labels:

David Edgerley Gates,

deception,

disinformation,

election,

information,

KGB,

Kremlin,

warfare

07 March 2017

PTSD and Human Remains

by Melissa Yi

“I hate how Miss Marple solves murders and remains completely unaffected by them,” said my friend Jessica. “I like that Hope is real.”

Dr. Hope Sze is real to me, too.

The problem is that Hope has gotten a little too real in my latest book, Human Remains.

After the hostage-taking in Stockholm Syndrome, Hope has post-traumatic stress. Which means I have a few problems, as a writer.

1. PTSD may not be compelling to read about. Hope is numb and antisocial and angry. Not the cute little pixie detective your average reader might want to get to know.

2. Hope has a lot of backstory. For starters, I have to mention the hostage-taking and the fact that she has two boyfriends, without too many spoilers.

3. Normal writer concerns: I try to set up character, setting, and a problem in the first paragraph, ideally in the first sentence. I also need to establish that she’s an Asian female physician and that the story is set in current-day Ottawa, Canada, just before Christmas. Finally, I have a clear voice for Hope.

Here are the first 201 words.

Next, I'm coding it based on these three main concerns.

You may argue about how successfully I've accomplished my goals, and how well I'm telling a story, which is the ultimate bar for a novel, but one of the things I like about writing is the problem-solving. You get more skilled, but there's always another part of the craft that needs work.

The "My name is Hope Sze" paragraph is not my first choice, because I prefer subtlety in explaining the hostage-taking backstory, but in the end, clarity and accessibility to new readers were more important than my poet's sensibility. Also, I feel like it's a tribute to Sue Grafton, because I would smile in recognition when she'd start off, "My name is Kinsey Millhone..."

I generally have to add setting in afterward. Mysteries are all about plot, to me; I already have Hope's character and voice; but especially for this one, where she works in a stem cell lab, I had to tour Dr. Bill Stanford's stem cell lab, quiz him and Dr. Lisa Julian, and still ask questions months later. Even then, Michelle Poilly, a local college science teacher, asked me pertinent questions about adding shakers to the virology lab or explaining plasmids differently.

I don't pretend to be a PTSD expert, either, but at the Writers' Police Academy last summer, I had the opportunity to meet Paul M. Smith and his service dog, Ted. Paul is a counsellor for traumatized officers and their families. Paul suffers from PTSD himself, so he has a service dog named Ted. At one point, when students surrounded Paul with questions, Ted came up to Paul, reared up on his rear legs, placed his paws on Paul’s shoulders, and looked him in the eyes, grounding him.

Maybe that's why Hope befriends a dog named Roxy in this book. I believe animals are a wonderful way to rebuild ourselves.

What about you? How do you balance all the information you have to convey with the story you must tell to hook the reader?

MD/Ph.D. Dr. Stephen M. Stahl points out that PTSD is an increasing problem. Of the soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, he estimates 1 in 1000 died, and 1 in 100 were injured, but as many as 1 in 5 ended up with a mental illness (PTSD, depression, or suicide). Twenty to thirty veterans die from suicide every day.

As writers and readers and citizens, how do we acknowledge these terrible realities, yet continue to create and shape a better world?

Dr. Hope Sze is real to me, too.

The problem is that Hope has gotten a little too real in my latest book, Human Remains.

After the hostage-taking in Stockholm Syndrome, Hope has post-traumatic stress. Which means I have a few problems, as a writer.

1. PTSD may not be compelling to read about. Hope is numb and antisocial and angry. Not the cute little pixie detective your average reader might want to get to know.

2. Hope has a lot of backstory. For starters, I have to mention the hostage-taking and the fact that she has two boyfriends, without too many spoilers.

3. Normal writer concerns: I try to set up character, setting, and a problem in the first paragraph, ideally in the first sentence. I also need to establish that she’s an Asian female physician and that the story is set in current-day Ottawa, Canada, just before Christmas. Finally, I have a clear voice for Hope.

Here are the first 201 words.

You may argue about how successfully I've accomplished my goals, and how well I'm telling a story, which is the ultimate bar for a novel, but one of the things I like about writing is the problem-solving. You get more skilled, but there's always another part of the craft that needs work.

The "My name is Hope Sze" paragraph is not my first choice, because I prefer subtlety in explaining the hostage-taking backstory, but in the end, clarity and accessibility to new readers were more important than my poet's sensibility. Also, I feel like it's a tribute to Sue Grafton, because I would smile in recognition when she'd start off, "My name is Kinsey Millhone..."

I generally have to add setting in afterward. Mysteries are all about plot, to me; I already have Hope's character and voice; but especially for this one, where she works in a stem cell lab, I had to tour Dr. Bill Stanford's stem cell lab, quiz him and Dr. Lisa Julian, and still ask questions months later. Even then, Michelle Poilly, a local college science teacher, asked me pertinent questions about adding shakers to the virology lab or explaining plasmids differently.

I don't pretend to be a PTSD expert, either, but at the Writers' Police Academy last summer, I had the opportunity to meet Paul M. Smith and his service dog, Ted. Paul is a counsellor for traumatized officers and their families. Paul suffers from PTSD himself, so he has a service dog named Ted. At one point, when students surrounded Paul with questions, Ted came up to Paul, reared up on his rear legs, placed his paws on Paul’s shoulders, and looked him in the eyes, grounding him.

Maybe that's why Hope befriends a dog named Roxy in this book. I believe animals are a wonderful way to rebuild ourselves.

What about you? How do you balance all the information you have to convey with the story you must tell to hook the reader?

And how do you talk about the serious issues in the world?

MD/Ph.D. Dr. Stephen M. Stahl points out that PTSD is an increasing problem. Of the soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, he estimates 1 in 1000 died, and 1 in 100 were injured, but as many as 1 in 5 ended up with a mental illness (PTSD, depression, or suicide). Twenty to thirty veterans die from suicide every day.

As writers and readers and citizens, how do we acknowledge these terrible realities, yet continue to create and shape a better world?

06 March 2017

Last Writes

by Steve Liskow

by Steve Liskow

A few weeks ago, I attended the funeral of a former colleague. I have to admit that I'm approaching an age where I--and several of my friends--find this happening more often than we like. But it made me stop and think for the first time how many of my own works involve funerals, too. So far, eight of my eleven novels have funeral scenes or scenes in which characters talk about a funeral. So do both my current WIPs and at least one short story.

That made me try to recall "great literary works" that have funerals in them, and I immediately thought of Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, Wuthering Heights, The Loved One, Hamlet, As I Lay Dying, and Antigone. There must be dozens of others, especially when you think of all the "great literary works" I've managed to avoid reading.

This makes sense because if a story doesn't have something at stake, the reader will stop reading and the audience will stop watching or listening. The two main issues that put something at stake are love and death because they cause irrevocable change. Love changes everything. Where would Romeo and Juliet be without it? Well, alive, you say. Exactly, I say.

Most of us in the crime writing biz focus on murder, not jaywalking or littering because it has a more profound effect on the people. My funeral scenes remind me--and my readers--that killing someone affects the survivors, too, the ones who have to carry on without that person who has been taken away. The protagonist has to figure out how and why so order can be restored, albeit differently. The friends no longer have that shopping companion or tennis partner. The lover no longer has his or her other half. The child(ren) no longer have that parent. The parent no longer has that child.

I sometimes use the funeral scene to provide a clue to the crime, but more often than not, I focus on the inner life of the characters for whom the landscape has changed. These people have to reinvent themselves in order to go on. We all do that many times in our lives (See Judith Viorst's Necessary Losses and Gail Sheehy's Passages for examples), but we crime writers grapple with it every time we put words on paper.

Maybe that's why I get annoyed when people look down at crime writers or romance writers as "mere genre fiction." Take away love and death, and what do you have left?

A few weeks ago, I attended the funeral of a former colleague. I have to admit that I'm approaching an age where I--and several of my friends--find this happening more often than we like. But it made me stop and think for the first time how many of my own works involve funerals, too. So far, eight of my eleven novels have funeral scenes or scenes in which characters talk about a funeral. So do both my current WIPs and at least one short story.

That made me try to recall "great literary works" that have funerals in them, and I immediately thought of Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, Wuthering Heights, The Loved One, Hamlet, As I Lay Dying, and Antigone. There must be dozens of others, especially when you think of all the "great literary works" I've managed to avoid reading.

This makes sense because if a story doesn't have something at stake, the reader will stop reading and the audience will stop watching or listening. The two main issues that put something at stake are love and death because they cause irrevocable change. Love changes everything. Where would Romeo and Juliet be without it? Well, alive, you say. Exactly, I say.

Most of us in the crime writing biz focus on murder, not jaywalking or littering because it has a more profound effect on the people. My funeral scenes remind me--and my readers--that killing someone affects the survivors, too, the ones who have to carry on without that person who has been taken away. The protagonist has to figure out how and why so order can be restored, albeit differently. The friends no longer have that shopping companion or tennis partner. The lover no longer has his or her other half. The child(ren) no longer have that parent. The parent no longer has that child.

I sometimes use the funeral scene to provide a clue to the crime, but more often than not, I focus on the inner life of the characters for whom the landscape has changed. These people have to reinvent themselves in order to go on. We all do that many times in our lives (See Judith Viorst's Necessary Losses and Gail Sheehy's Passages for examples), but we crime writers grapple with it every time we put words on paper.

Maybe that's why I get annoyed when people look down at crime writers or romance writers as "mere genre fiction." Take away love and death, and what do you have left?

Labels:

death,

Funerals,

stakes in stories,

Steve Liskow

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

05 March 2017

Behind Closed Doors

by Leigh Lundin

B. A. Paris’ Behind Closed Doors represents another in a long series of HIM— ‘husband is monstrous’— novels, also known as HIS, HIT, HIC (husband is sociopath, toxic, cruel) etc. They’re everywhere. The last one I read (and saw as a film) was The Girl on the Train. Both were recommended by my writer/editor friend Sharon.

It comes as no surprise that half the population devour these books with glee. The key to bridging the gender gap in Women Good / Men Bad literature is whether the author can bring the bad guy convincingly to life. Therein lies the strength of Closed Doors but also its main shortcoming.

Behind Closed Doors is the story of a woman whose nightmare begins when she marries a lawyer. Bad first move of course, but matters immediately grow worse, much worse. No matter how stepfordized she becomes, her situation can never improve but only deepen and darken.

I didn’t fall easily into the story. I wrote Sharon,

The part about ‘said’ refers to speech tags, which Rob Lopresti calls unnecessary stage directions. Fancy speech tags ‘tell, not show.’ In other words, if the dialogue is strong enough, a writer shouldn’t have to sit down with a thesaurus and tell the reader what to think or feel. The rule isn’t absolute, so we’re taught if we must use supplemental speech tags, to make certain they actually mean to communicate, to pass on words through talking. ‘Frowned’ and ‘smiled’ fail that test but it didn’t stop the author from employing them.

Right about now, the author is probably sticking voodoo pins in a Leigh doll ($5.99 at the SleuthSayers store), but bear with me, our policy is to write why we like books. Besides, this is a first-time author, so getting a book out in this market is a success in itself.

After finishing the book, I wrote to Sharon again,

For once, I would have loved to know more about secondary characters, especially Esther, but as we discover, Esther isn’t merely a secondary character.

Unlike The Girl on the Train, the author doesn’t play around trying to fool us. From the outset, we learn this man who came into her life is one sick, well… I can’t think of a sufficiently awful word to describe him.

Paris has created one of the most evil antagonists ever, one who makes Gregory Anton / Sergius Bauer / Jack Manningham (Gaslight) seem like a maladjusted schoolboy. For someone who breaks a heart for enjoyment, there should be a special Dantean subcircle, but this fiend goes several levels worse. I reached a point I felt no ill could match what this guy deserved.

Shortly past the halfway mark, I began to see how this must end. The payoff was worth the trip. In approval, I sipped a glass of sherry, a special red from the Montilla region of Spain. Taste the story; I think you’ll like it.

It comes as no surprise that half the population devour these books with glee. The key to bridging the gender gap in Women Good / Men Bad literature is whether the author can bring the bad guy convincingly to life. Therein lies the strength of Closed Doors but also its main shortcoming.

Behind Closed Doors is the story of a woman whose nightmare begins when she marries a lawyer. Bad first move of course, but matters immediately grow worse, much worse. No matter how stepfordized she becomes, her situation can never improve but only deepen and darken.

I didn’t fall easily into the story. I wrote Sharon,

“I’m finding Behind Closed Doors … well, uncomfortable. 160 pages in, I keep looking for a place to grab hold, mainly a character to really like. It’s not that I dislike the protagonist but it’s taking time to reveal her. … The writing is a bit high-schoolish with godawful word substitutions for ‘said’. One I remember was “Blah, blah, blah,” he smoothed. But I’m trusting the plot will pay off.”Eventually it did.

The part about ‘said’ refers to speech tags, which Rob Lopresti calls unnecessary stage directions. Fancy speech tags ‘tell, not show.’ In other words, if the dialogue is strong enough, a writer shouldn’t have to sit down with a thesaurus and tell the reader what to think or feel. The rule isn’t absolute, so we’re taught if we must use supplemental speech tags, to make certain they actually mean to communicate, to pass on words through talking. ‘Frowned’ and ‘smiled’ fail that test but it didn’t stop the author from employing them.

Right about now, the author is probably sticking voodoo pins in a Leigh doll ($5.99 at the SleuthSayers store), but bear with me, our policy is to write why we like books. Besides, this is a first-time author, so getting a book out in this market is a success in itself.

After finishing the book, I wrote to Sharon again,

“The payoff in the last chapter was worth it– I really liked how Esther involved herself. The writing became stronger as it neared the end, where her internal dialogue of her fear and hope takes over as events wrap up in Thailand and she rehashes everything in her mind during the flight home.”As I touched upon earlier, characterization proves to be the author’s weakness and great strength. Until the final fifth of the book, I found it difficult to identify with the narrator/heroine. I’m ashamed to say I couldn’t quite decide why– after all, she’s a devoted sister and a potentially loving wife. Yet one gem leapt out to bring our protagonist into focus. As an artist, she created a large painting for her fiancé, literally kissing the canvas using differing shades of lipstick. That’s a lovely hint what she’s like and I wanted more. This is why I stayed with the book despite early reservations.

| Behind the Door |

|---|

| Behind Closed Doors is another in a series of novels brought to my attention by my friend Sharon– teacher, editor, writer, my friend Steve’s inamorata. She analyzes recommendations from magazines, the Oprah Book Club, and featured reads from her local library web site. Of her choices, Gone Girl remains my favorite. |

Unlike The Girl on the Train, the author doesn’t play around trying to fool us. From the outset, we learn this man who came into her life is one sick, well… I can’t think of a sufficiently awful word to describe him.

Paris has created one of the most evil antagonists ever, one who makes Gregory Anton / Sergius Bauer / Jack Manningham (Gaslight) seem like a maladjusted schoolboy. For someone who breaks a heart for enjoyment, there should be a special Dantean subcircle, but this fiend goes several levels worse. I reached a point I felt no ill could match what this guy deserved.

Shortly past the halfway mark, I began to see how this must end. The payoff was worth the trip. In approval, I sipped a glass of sherry, a special red from the Montilla region of Spain. Taste the story; I think you’ll like it.

Labels:

B.A. Paris,

husbands,

Leigh Lundin,

wives

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

04 March 2017

Let's Do the Twist

by John Floyd

by John M. Floyd

In his book Spunk & Bite, author and publisher Arthur Plotnik says, "Readers love surprise. They love it when a sentence heads one way and jerks another."

In his book Spunk & Bite, author and publisher Arthur Plotnik says, "Readers love surprise. They love it when a sentence heads one way and jerks another."How true. And what works in language/style also seems to work--at least in this case--in plots. Readers, and viewers too, like it when the story takes a sudden and unforeseen turn. Sometimes it's just a side street that eventually leads us back to the freeway, but occasionally it's a major roadblock that sends us off in a totally different direction, or even headed back the way we came.

Off-balancing act

FYI, I'm not talking specifically about surprise endings, like those in Shutter Island, Primal Fear, The Sixth Sense, Fight Club, Planet of the Apes, Presumed Innocent, The Usual Suspects, "The Lottery," "The Gift of the Magi," etc. The reversals I'm talking about can also occur earlier in the story.

Nobody who reads fiction (or watches movies) wants the characters to have an easy, carefree ride. We want our hero or heroine to be challenged, and not only with that initial "call to adventure." We want him or her weighted down with burdens and decisions and constantly-changing threats. And the main thing, here, is changing. Since we as human beings are always worried about changes in our own lives, we as readers are worried when characters face changes--illness, death, divorce, a new job, loss of a job, a new location, strangers who come to town, and so forth--and have to deal with them. It adds to the "uncertainty of outcome" that's such an integral piece of storytelling. This happens in all good stories, but a part of that, especially in genre fiction, is injecting twists and turns throughout the tale.

Shock treatment

I always enjoy movies and novels that contain those in-flight reversals. There are many examples, but the following stories--all of them are films and most were books as well--come to mind because they feature a sudden 180-degree switcheroo in or near Act II: A Kiss Before Dying, Psycho, L.A. Confidential, Executive Decision, Ransom, Gone Girl, Deep Blue Sea, Marathon Man, etc. And I don't mean a slight swerve off the path; I mean a clap-your-hands-over-your-mouth and bug-out-your-eyes stunner that completely changes the course of the story.

The reversals in the movie versions of Psycho and L.A. Confidential were especially memorable because--in each case--the best-known actor in the cast was unexpectedly killed in the middle of the story (early middle in Psycho, late middle in LAC). That also happened when the most famous actor in Game of Thrones bit the dust (well, his severed head did) in the final episode of the very first season. It left viewers thunderstruck, and understandably wondering what other off-the-charts events might happen, and when. If long-term tension is what you're trying to create (as a writer/director) and what you enjoy (as a reader/viewer), this is a pretty effective plot device.

It occurred to me, while I was writing this, that one definition of the word reversal is "a setback, or a change of fortune for the worse"--as in, I suppose, a deep dip in the Dow Jones--and I think that definition holds true for today's topic as well. Reversals in fiction are often for the worse, and that can help the story. More conflict, and more agony for the protagonist, means more suspense.

A sense of misdirection

Other tales that had big mid-story twists: The Maze Runner, Reservoir Dogs, The Departed, "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," Life of Pi, Sands of the Kalahari, A History of Violence, The Hateful 8, Blood Simple--and almost any short story by Roald Dahl and any novel by Harlan Coben. Those two authors were/are masters of the plot reversal.

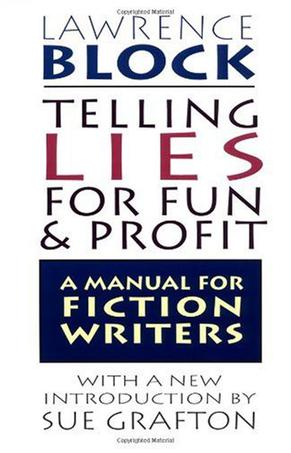

With regard to endings, Lawrence Block had an interesting observation about that in his book Telling Lies for Fun and Profit. He said, "The best surprise endings don't merely surprise the reader. In addition, they force him to reevaluate everything that has preceded them, so that he views the actions and the characters in a different light and has a new perspective on all that he's read."

With regard to endings, Lawrence Block had an interesting observation about that in his book Telling Lies for Fun and Profit. He said, "The best surprise endings don't merely surprise the reader. In addition, they force him to reevaluate everything that has preceded them, so that he views the actions and the characters in a different light and has a new perspective on all that he's read."At the risk of repeating myself, I think the same thing applies to twists and reversals during the course of the narrative. If you're good enough, you can use reversals to keep a reader off-balance and still maintain the central storyline. The diversions, when included, should be there for a reason, and not just for shock value and entertainment. The twists should fit in and be logical, and should--ideally--make the journey more interesting to the traveler.

Questions

Do you agree? Is that something you try to do in your own writing, or look for in your reading and/or viewing? What are some of your favorite reversals in movies, novels, and stories? Can you think of some that didn't work well? Which ones surprised you the most? I think I actually spilled Coke on the people around me in the theater when Janet Leigh met her fate in the Bates Motel (that bombshell seemed to drop almost as soon as I got settled into my seat), and I choked on my popcorn when the guy pushed his date off the roof of the building in the first half of A Kiss Before Dying. I'll remember those scenes always. And that's more than I can say for a lot of the novels I've read and the movies I've seen lately.

In real life, certainty and security are comforting. In fiction, the future is always unpredictable.

Or should be.

03 March 2017

Reviewing the Reviewers

by Art Taylor

By Art Taylor

One of the courses I'm teaching this semester at George Mason University is titled "Crafting and Publishing Reviews," and we've been looking not only at the various types of reviews out there (a big difference between a lengthy essay in The New York Review of Books, for example, and a three-paragraph review in Entertainment Weekly) but also at the longer history of reviewing and the larger landscape of questions about how reviews are read and how they should be written. I've been fortunate to contribute reviews to a number of publications over the years, including the Washington Post, the Washington Independent Review of Books, and Mystery Scene, just as a sampling, and I've been grateful during this course to welcome the voices of even more experienced critics into the classroom via Google Hangouts, including Washington Post critic Ron Charles and freelance critic Mark Athitakis so far; next week, we'll host Kristopher Zgorski of BOLO Books to talk about book blogging and book advocacy, and more guests are on the syllabus ahead.

This past Wednesday's class was focused on the ethics of reviewing, and I'll share links to some of that reading here (click on the titles to reach the articles):

I'm not sure how the nuanced and troubling the students found the readings (the view from my side of the class discussion likely much different from their view), but I was struck by many of the conflicts and even contradictions in different viewpoints.

The column on John Updike's rules champions the "role social responsibility of the critic" by building on E.B. White's call for writers to "life people up, not lower them down." A couple of the columns stressed the need for fairness in reviewing—not only in terms of being fair to the book being reviewed by specifically by avoiding conflicts of interest in several directions: reviewers shouldn't be friends with the authors they're reviewing, nor should they be enemies, perhaps for obvious reasons.

And yet in contrast, there are concerns that too much politeness might lead, in Julavits' words, to "dreckish handholding" and a "trumpeting of mediocrity," and Shafer said more frankly, "The point of a book review isn't to review worthy books fairly, it's to publish good pieces"—and he pointed to the "British model" of assigning "lively-but-conflicted writers" to create greater tension (and perhaps draw more readers).

Perhaps most interesting to my mind was the idea of how to approach a book in the first place. An earlier reading from our syllabus—Lynne Sharon Schwartz's "The Making of a Reviewer" from the collection Book Reviewing, edited by Sylvia E. Kamerman—championed the idea of treating a new book as a "strange new geological treasure" to be judged for "its intrinsic, living qualities" (a contrast to what Schwartz called "negative criticism," the idea of appraising a book "on the basis of what it has failed to accomplish, with these failings usually derived from the critic's own notion of how he or she would have handled the subject"). In Julavits' essay, however, New Yorker critic James Wood is praised for his "idealism":

Approach a new book with some naivete or innocence? or with the full force of your belief system behind you?

I recognize that not all readers here are reviewers, but we are indeed readers—and I'm curious how you approach a new novel. Filled with expectations and armed with standards? Or willing to see where the author might take you? Or can there be overlap between those approaches?

One of the courses I'm teaching this semester at George Mason University is titled "Crafting and Publishing Reviews," and we've been looking not only at the various types of reviews out there (a big difference between a lengthy essay in The New York Review of Books, for example, and a three-paragraph review in Entertainment Weekly) but also at the longer history of reviewing and the larger landscape of questions about how reviews are read and how they should be written. I've been fortunate to contribute reviews to a number of publications over the years, including the Washington Post, the Washington Independent Review of Books, and Mystery Scene, just as a sampling, and I've been grateful during this course to welcome the voices of even more experienced critics into the classroom via Google Hangouts, including Washington Post critic Ron Charles and freelance critic Mark Athitakis so far; next week, we'll host Kristopher Zgorski of BOLO Books to talk about book blogging and book advocacy, and more guests are on the syllabus ahead.

This past Wednesday's class was focused on the ethics of reviewing, and I'll share links to some of that reading here (click on the titles to reach the articles):

- “John Updike’s 6 Rules for Constructive Criticism,” reprinted in The Atlantic

- “The Book Review: Who Critiques Whom—And Why?” by Byron Calame, The New York Times, December 18, 2005

- “Fair is Square: The Case for Hiring Biased Book Reviewers,” by Jack Shafer, Slate, August 12, 2005

- A Case Study: Dale Peck, Rick Moody & More:

- “The Moody Blues” by Dale Peck, a review of Rick Moody’s The Black Veil, The New Republic, July 1, 2002

- “Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!” by Heidi Julavits, The Believer, March 2003

- “The Good of a Bad Review” by Clive James, The New York Times, September 7, 2003

I'm not sure how the nuanced and troubling the students found the readings (the view from my side of the class discussion likely much different from their view), but I was struck by many of the conflicts and even contradictions in different viewpoints.

The column on John Updike's rules champions the "role social responsibility of the critic" by building on E.B. White's call for writers to "life people up, not lower them down." A couple of the columns stressed the need for fairness in reviewing—not only in terms of being fair to the book being reviewed by specifically by avoiding conflicts of interest in several directions: reviewers shouldn't be friends with the authors they're reviewing, nor should they be enemies, perhaps for obvious reasons.

And yet in contrast, there are concerns that too much politeness might lead, in Julavits' words, to "dreckish handholding" and a "trumpeting of mediocrity," and Shafer said more frankly, "The point of a book review isn't to review worthy books fairly, it's to publish good pieces"—and he pointed to the "British model" of assigning "lively-but-conflicted writers" to create greater tension (and perhaps draw more readers).

Perhaps most interesting to my mind was the idea of how to approach a book in the first place. An earlier reading from our syllabus—Lynne Sharon Schwartz's "The Making of a Reviewer" from the collection Book Reviewing, edited by Sylvia E. Kamerman—championed the idea of treating a new book as a "strange new geological treasure" to be judged for "its intrinsic, living qualities" (a contrast to what Schwartz called "negative criticism," the idea of appraising a book "on the basis of what it has failed to accomplish, with these failings usually derived from the critic's own notion of how he or she would have handled the subject"). In Julavits' essay, however, New Yorker critic James Wood is praised for his "idealism":

Wood is peevish, even occasionally mean, but never snarky. He is perpetually disappointed with “us,” (if you’re a writer, even one he’s never written about, you cannot help but feel you’ve let him down)—which is certainly better than being too jaded to be much more than dismissively irritated, too disdainful of fiction to do much more than toss clichéd disparagements around... and call it criticism. Wood makes people hopping mad, yes, but despite his grumbly excoriations there’s usually room for a dialogue with Woods, which indicates there’s something to wrangle over, i.e., his claims are based on a strongly-held (and felt) belief system, and he’s an intellectual, which means he likes to be forced to defend that belief system.

Approach a new book with some naivete or innocence? or with the full force of your belief system behind you?

I recognize that not all readers here are reviewers, but we are indeed readers—and I'm curious how you approach a new novel. Filled with expectations and armed with standards? Or willing to see where the author might take you? Or can there be overlap between those approaches?

02 March 2017

"L'Etat, C'est Moi"

by Eve Fisher

|

| Louis XIV, in his glory |

Louis XIV (1638-1715) became king when he was five years old. Of course, they didn't let him actually rule at that age - he had a minister, Cardinal Mazarin. (Suspected by some of being his mother's lover and/or husband. But not by me: Anne of Austria was a true European aristocrat, who would sooner have eaten merde as have anything physical to do with a jumped-up Italian.) Mazarin, according to Louis XIV, kept him living in poverty, barely educated. It could be true.

NOTE: Children, even royal children, weren't as prized back in the day as they are now. Classic example, Charles Maurice Talleyrand-Perigord, the eldest son of his house, who was put out to nurse in the countryside for his first few years. He returned lame. His parents then made his younger brother the heir, and put our boy into the Church, where he became the most dissolute, loose-living, atheistic Bishop of Autun since... who knows when. (Eventually, he joined the French Revolution, managed to switch sides with such persistent effectiveness that he survived everything, from the Reign of Terror to Napoleon to the Bourbon Restoration...)

SECOND NOTE: Louis XIV's only sibling, his younger brother Philippe, who was universally called Monsieur, had a VERY interesting upbringing. He was deliberately raised to be a homosexual, or at the very least a transvestite; his mother and her ladies encouraged him to dress up in women's clothing, make-up, jewelry and hairstyles. He was deliberately kept from any formal education other than the 3 r's, and any knowledge of statecraft. All of these were so that he'd never be a rival for his brother. The result was a man who was bisexual, surprisingly martial, and through his two marriages, became the "grandfather of Europe", ancestor of every Roman Catholic royal house in Europe. You never know...Back to Louis, who would have been infuriated by that digression. Louis' childhood influenced him in many ways, but it was the Fronde (1648-1653) that created his ruling style. The Fronde was a multiplicity of rebellions that had no order, rhyme, or reason to any of it. Of, by, and for the nobility, the Fronde's goal was to return to the good old days when a nobleman could rule his lands and provinces as a petty king, with absolute power. And there had been no jumped-up clergymen (Richelieu and Mazarin) to try and make them knuckle under to some Bourbon king.

NOTE: Part of the problem was that in class-ridden pre-modern Europe, the Bourbons weren't that old a family. One of Louis' mistresses, Madame de Montespan, often bragged to his face that her family, the House of Rochechouart was MUCH older than his, and it was. Hers went back to the 800s; his only to the 1200s.

|

| Episode of the Fronde at the Faubourg Saint-Antoine by the Walls of the Bastille (i.e., when the royal family had to flee Paris. See below) |

- The nobility will have no role in government at all.

- All non-military government roles, positions, and titles will be given to the bourgeoisie (that way, Louis can fire them whenever he wants).

- Parlement's only role will be to rubber-stamp his decisions.

- Paris can rot.

- He, Louis XIV, will rule personally, absolutely, with no prime minister, all his life.

And the key to doing that, successfully, was:

- to appoint good bourgeois officers (Jean-Baptist Colbert, Comptroller-General; Michel le Tellier, and his son, Louvois, both Ministers of War and Chancellor, among others).

- to personally work like a horse, non-stop, day in and day out

- to distract the nobility with endless perks, entertainment, prizes, all dependent upon HIS favor.

Welcome to Versailles.

Versailles was the old hunting lodge of Louis XIII, 12 miles south of Paris. Louis XIV loved it, despite the fact that it was in the middle of a swamp. He had it remodeled - in fact, it was being remodeled for his entire reign, and some say that the construction is still on-going - and announced, early on, that Versailles was the seat of government. If you wanted to be close to the king (and who didn't?) you went to Versailles. And everyone who could went.

|

| The Duc de Saint-Simon |

But things were different then. Comfort, so important to us today, was held in contempt. The mark of a man of quality was "indifference to heat, cold, hunger and thirst." Magnificence was the order of the day. The nobility lived in chateaus that were drafty, cold, smoky, and reeked of human and animal waste (there was no indoor plumbing). But the rooms looked beautiful. The nobility wore velvets and satins and brocades in summer as well as winter, and the clothes always stank because they couldn't be washed, and people generally stank because they didn't bathe, just kept pouring on the perfume. Louis himself just got rubbed down with scented alcohol every day. But by God they looked marvelous.

Versailles almost bankrupted Paris. Louis never went there. He frowned on any nobility who went there. When the court needed a change of air, they went to Fontainebleau and Marly. Paris was ignored. For decades. But their revenge would come in 1789...

Versailles almost bankrupted Louis (although he never admitted it, and burned the receipts)...

Versailles bankrupted the nobility.

- Living at Versailles meant, for one thing, that the country estates (and in France, being noble meant you had a large country estate that supplied you with an income) were managed by someone else, who certainly wasn't going to send you all the money.

- The King expected his nobles to be well-dressed, and the velvets, silks, and satins, with gold and silver embroidery did not come cheap. And he expected to see new outfits for weddings, births, Feast Days, parties, etc. The Duc de Saint-Simon spent 800 louis d'or for new outfits for himself and his wife for the Duc de Bourgogne's wedding - that was equivalent of $96,000.00 in today's money.

- While much of the constant entertainment at Versailles was free (watching Louis was the major entertainment, from his morning rub to his official coucher with the Queen), including hunting, music, plays, concerts, dances, and the usual amount of drink, drugs, and sex (all right, sometimes more than the usual amount) there was also gambling almost every night. They played vingt-et-un, which is blackjack, as well as roulette and dice. (The King preferred billiards. He generally won.) The stakes could run exceedingly high: Madame de Montespan (of the excellent bloodline) lost 3 million francs in one evening.

- You have to have servants, sedans, dogs, horses, hunting equipment, stable rent, bribes, and... let's put it this way, books of the day said that a single man of wealth and nobility should have at least 36 servants, 30 horses, etc.... Of course, if you married, expenses doubled, and if you had children...

And Louis was always present. How he lived his life I do not know. Louis spent his entire day, from 7:45 a.m. to midnight, in public. (We know where he was every second of every day, because he followed a time-table as rigid as that of a German railroad.) He had an iron constitution, an iron will, an iron work ethic, and he was always on stage. He was never alone, even when he was sleeping, using the toilet or having sex. Not only was someone there, there were a lot of people there, perhaps discreetly looking away. (Probably not.) This was rule by King as rock star, the first total celebrity, the first reality TV show. To see him, to be seen by him, to watch him eat, drink, dress, dance, walk, ride, hunt, etc., was everyone's obsession. And it was considered as much of an honor, if not more, to attend him while he was using the bathroom as when he was holding full court.

And Louis was always present. How he lived his life I do not know. Louis spent his entire day, from 7:45 a.m. to midnight, in public. (We know where he was every second of every day, because he followed a time-table as rigid as that of a German railroad.) He had an iron constitution, an iron will, an iron work ethic, and he was always on stage. He was never alone, even when he was sleeping, using the toilet or having sex. Not only was someone there, there were a lot of people there, perhaps discreetly looking away. (Probably not.) This was rule by King as rock star, the first total celebrity, the first reality TV show. To see him, to be seen by him, to watch him eat, drink, dress, dance, walk, ride, hunt, etc., was everyone's obsession. And it was considered as much of an honor, if not more, to attend him while he was using the bathroom as when he was holding full court.NOTE: To show how great the obsession with Louis was - and how tough a bird he was - in 1686, he underwent an operation, without anesthesia, on an anal fistula. In public. Amazingly, he survived. Even more amazingly, a huge number of nobles went to the doctor to be checked to see if they had an anal fistula, and those who did boasted about it! Now THAT's toadying.

|

| Portrait sculpture of 18th C. French peasants, by artist George S. Stuart Museum of Ventura County |

In case you're wondering, this was an age in which it was assumed, by everyone, that government had nothing to do with and no obligations towards the common people (peasants and artisans, who made up 95% of the population, along with a smattering of merchants), other than to collect taxes from them. The wealthy paid no taxes at all. Neither did the Church. The peasants paid for everything. They got nothing. Any improvements, in roads, bridges, canals, etc., were paid for either by the goodness of the local lord or a whim on the part of the king. There were no social services, no pensions, no health care, nothing. Peasants worked until they dropped, and then died. Government was there to support the king, the nobility, the Church, and to wage war.

|

| William of Orange defeating Louis XIV at Naarden |

Louis succeeded in what he wanted to do. He kept the nobility powerless and he kept himself absolute monarch for 72 years. But he almost destroyed France in the process. He came to the throne of the most powerful, most populous, most wealthy country in Europe, and left it in debt, surrounded by enemies, crippled by a tax system that, depending as it did entirely on the poor, was so bad that in, 70 years, it would spark a revolution.

Much the same results came from all the absolute monarchs of the 17th and 18th centuries - endless wars, fighting over and over and over again over the same territories, bankrupting entire countries, and leading, finally, to the almost constant revolutions of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The pursuit of war and glory - by leaders who cannot be told "No" - and its results can be summed up by Thomas Gray:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

- Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, 1751

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)