[I had thought to preempt this post with remarks about SKYFALL, the newest Bond picture, the best in years, and I decided, not; or to comment about the fall of David Petraeus, but anything I had to say would be speculation at this point.]

Alan Furst, no more than Charles McCarry, shouldn’t need an introduction, or at least I hope not. He was, for a time, something of an acquired taste, but then a hot agent got ahold of him, he jumped publishers, and they turned him into a household name, at least in my household.

He himself names Eric Ambler as a chief influence, and you can easily see it. The darkened Polish railway stations, or perhaps French, the dubious alliances, the quiet men in the shadows who admit no loyalty either way, or the loud patriots that generally don’t survive chapter two. This is the slippery no-man’s-land of real espionage.

The earlier books, NIGHT SOLDIERS, for example, work on a broad canvas: the Iron Guard, the Spanish Civil War, the world war itself, and even after. The later books curl in on themselves, narrower, more hermetic, if no less fluent and convincing, but sideshows of sideshows, Greece, or Norway. The trick is that we know how the war turned out. But in 1939, or 1940, or even 1943, nobody on the ground had any real confidence Hitler was going to be beaten. And his proxies were everywhere, the Fascists going after the Italian press in exile (THE FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT), or a local cop trying to save Jews leaving Germany (SPIES OF THE BALKANS), knowing the Gestapo already have him in their sights. They are often stories about everyday heroism, and if not bravery, then endurance.

THE WORLD AT NIGHT came out in 2002. One reviewer remarked that it was like seeing CASABLANCA for the first time. I think this is pretty much on the money. “These papers have expired…” Paris, the German occupation. Gas rationing, and so on, ordinary and everyday life made inconvenient, if not always for the privileged. The guy at the center of the story is a French movie producer, who keeps working under the Nazis. He makes silly comedies, nothing politically inconvenient. Because he can move easily between France and Portugal, or France and Italy, he comes to the attention of British intelligence, and this of course bodes ill. But the point of the story isn’t the spook shit, it’s his increasing moral burden. It reminds me of André Cayatte’s PASSAGE DU RHIN (TOMORROW IS MY TURN in American release, terrible title), which is also about the occupation of Paris, ambiguous loyalties, and difficult personal choices.

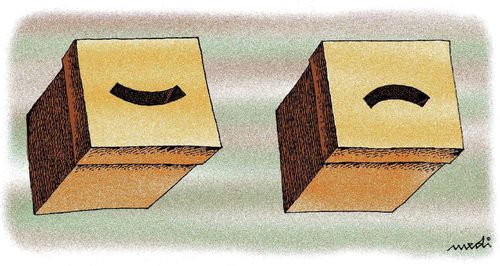

The question posed in THE WORLD AT NIGHT is how we ourselves might behave, not in the face of inhumanity, per se (the Holocaust is far off the page), but in the actual daily humiliation of living under an occupying power. Why and how would we resist, or would we simply accept it? The dog barks, the caravan passes. The lights stay on, the cafés and brasseries are open, the wine gets poured, the choucroute garni is served. “This ought to take the sting out of Occupation,” Sam says in CASABLANCA, lifting his glass to toast Ilsa and Rick. The difference, in Furst’s story, is the lack of romance– Casson, the hero, gets into bed with enough good-looking women, but it’s not romantic in the sense of being a fairytale, of taking place in a world of heightened, and reductive, passions. The book is anchored in very simple, pedestrian realities. What the guy gets sucked into could easily get him killed. (There’s a terrific set-piece of a jailbreak, for instance.) And something else, that his choices are incremental, as ours in life so often are. They aren’t sudden. They don’t add up to a turning of the earth, until it’s too late to go back on them. Casson, essentially, backs himself into a place of no retreat. It feels very real, but also entirely necessary, as if, without foreknowledge, he took the path of least resistance, and found himself, or honor, something he never expected.

The ending is a jaw-dropper, which I won’t give away. Suffice it to say that it seems so uncharacteristic, but when looking back over the book, so utterly characteristic, it takes your breath away. I was flattened by it.

Heroes, like spies, often wear odd uniforms, and change their clothes more than once, if not their stripes. THE WORLD AT NIGHT is about a man who refuses to change his clothes. It’s about the intransigence of human nature, or its resilience. We’re mortal, and of course weak. When we rise to the occasion, as some of us have, it’s generally accident. Here, too. But the occasion of accident doesn’t mean our motives are false. Intentions count for little, in the end. To my mind, this is why THE WORLD AT NIGHT is so compelling: a man’s worth is in what he does, not in who he hopes or imagines himself to be.

S

S