We’ll get to all of that. But let’s start out with Jesse James.

|

| Jesse and Frank James, 1872 |

After the war, Jesse and Frank, perhaps as early as 1866, began their infamous run of bank and train robberies. By and large the James-Younger gang targeted banks run by Republicans who had stood against the Confederacy during the Civil War, and they didn’t shy away from killing anyone they suspected of Union sentiments. (It’s little wonder that the Kingston Trio’s version of Jesse James added a new line – “Jesse never did a worthwhile thing.”) In any event for years the gang eluded capture with the assistance of Confederate sympathizers in Missouri – indeed, in the 1870s the rivened state legislature only narrowly defeated a bill that would have granted full amnesty to the gang notwithstanding those robberies and murders. But the authorities, outraged by an 1876 robbery of the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota and the accompanying bloodshed, eventually mounted a relentless manhunt. Within weeks most of the gang was either killed or captured; only a very few, including Jesse and Frank, were still alive and at large.

|

| Robert Ford (The Dirty Little Coward) |

And so the story of Jesse James ends, right? Well not quite. Still a few carnivals to go.

|

| Lester B. Dill |

Saltpeter, however, was far from Dill’s interest. He renamed the cave Meramec Caverns, after the Meramec River that flows nearby, and began remodelling the huge cavern, which had earlier been used for dance parties by the residents of Stanton, into a show cave, open, for a fee, to the public. Over the years Dill aggressively sought to expand the caverns, and achieved notable success in this regard in 1941, with a discovery that (at least in Dill’s mind) tied the cave to the exploits of the James Gang. The discovery is explained as follows in an article by Phil Dotree at InterestingAmerica.Com.

The connection between Meramec Caverns and Jesse James remained obscure until the summer of 1941, when a rather severe drought hit the area and the water table dropped. Cave guides noted a change in a small pool of water that spilled out of a “dead end” wall. The ever-inquisitive Lester B. Dill decided to go under the wall, through the water, and see what was on the other side. . . . Dill found yet another large network of subterranean passages that fanned out into the limestone . . . .

Acting on his discovery, Dill immediately began constructing an access tunnel that would allow the new section of the caverns to be opened to the public. Dill also claimed that he had found various artifacts in the new caverns, although it is unclear when that claim was first made. But what is clear is that by 1948 the artifacts and Meramec Caverns were linked to Jesse James when a 100 year old man named J. Frank Dalton woke up one morning in his cabin in Oklahoma and declared that he was in fact Jesse.

|

| J. Frank Dalton (Jesse James?) |

Stanton, Mo. - The old man who looks, acts, and talks like Jesse James, and who claims, at 102 years of age, to be Jesse James, says that the man who was killed and buried as Jesse James was a fellow named Charlie Bigelow.

. . . The old man says he had him a string of runnin' horses, and two come down with distemper. 'I fetched 'em to St. Joe to isolate 'em,' he said. 'I had a house there I was not usin' for a spell - not until after some runnin' races at Excelsior Springs. This fellow Charlie Bigelow looked enough like me to be my twin, and he was huntin' a house. I told him and his wife they could use my place for a spell, until after the races, and he moved in.

One day I was out in the barn doctorin' my horses when I heard a gunshot in the house. When I heerd that gun go off I knowed it wasn't no play-party, because we argued with guns in them days. I run into the house and there was Bob Ford, standing over Bigelow with a gun in his hand and blood on the floor. I said to Ford, 'Looks like you killed him, Bob,' and Bob says, 'Looks like I did, Jesse.' Then I says, 'This is my chance, Bob. You tell 'em its me you killed. You tell my mother to say so, and you take care of that Bigelow woman. I'm long gone.'

The old man says he got on one of his horses - a good horse, a four-mile horse - and he lit out.

Thereafter, according to Dalton, he assumed his new identity, eventually settled in Oklahoma, and lived a relatively peaceful 60 years in anonymity.

| Meramec Caverns brochure from the 1950s featuring Frank Dalton and his story |

Thereafter, the artifacts that Dill claimed to have found in the newly opened section of the caverns were displayed at the entrance of the cave, and they included a strong box purportedly linked to a train robbery the James Gang orchestrated at Gads Hill, Missouri, in 1874. Dill also collected various sheriffs’ reports and eyewitness accounts that purportedly linked Jesse James to the caverns, and began an extensive billboard advertising campaign along old Route 66 -- generally painted, for free, on the roofs of barns along the highway -- proclaiming that Meramec Caverns was, in fact, Jesse James hideout.

Although J. Frank Dalton had various scars consistent with wounds that Jesse had reportedly received, and seemed to know many details about Jesse’s exploits, he ultimately was discredited in the eyes of many by a host of inconsistencies in his story. In the late 1960s Dill's son-in-law Rudy Turilli offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who could prove that Dalton was not Jesse. Relatives of Jesse James, including his daughter-in-law, responded with affidavits from family members who had previously positively identified the man shot by Robert Ford as Jesse. A Missouri court agreed with their proof and ordered Turilli (and presumptively Meramec Caverns) to pay the amount as damages for having falsely used Dalton's story, and Jesse James' "good" name, to advertise the caverns. But Dalton's story, along with legends of lost treasure and secret Confederate societies, continues to run rampant on the internet.

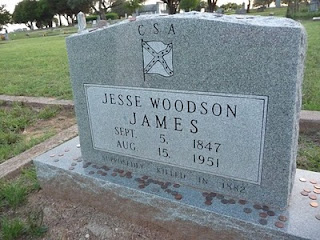

So what happened to Dalton? He eventually left his cabin at Meramec Caverns, traveled to Texas and died there on August 15, 1951 three weeks shy of his 104th birthday. His tombstone, notwithstanding that Missouri court ruling, is inscribed with the name "Jesse Woodson James."

|

| J. Frank Dalton's tombstone |

There have been at least two attempts to exhume Dalton’s body for DNA testing, the first of which, in 1995, purportedly showed a 99.5% chance that Dalton was not Jesse James. Similarly, an early exhumation of Jesse’s body – the one shot by Robert Ford – yielded a DNA sample consistent with that of Jesse’s then-living descendants. But the legitimacy of the DNA tests has been debated feverishly, and the conspiracy theorists persist, as any trip to that same friendly internet will reveal.

Was Dalton’s tale, and Dill’s use of that tale to advertise his cave, pure fiction? As noted above, there is still debate on that subject. What can we as mystery writers and readers add to the discourse? Maybe just a few things. Let’s look at some of the evidence discussed above.

|

| Postcard map of Meramec Caverns. Note Loot Rock at center, previously inaccessible except by swimming under a stone barrier wall |

First, the hideout theory. Dalton claimed, to the joy of cave owner Lester B. Dill, that the James Gang regularly used Meramec caverns as a hideout. Indeed, guided tours of the cave to this day proudly display “Loot Rock,” where Dalton claimed the James gang divided up their ill gotten gains. But take a look at the map on the right, and remember the story of how Dill found the portion of the cave in question in 1941 -- the entrance was under water until a season of heavy drought. And the entrance now used by tourists to get to that portion of the cave was carved out of the rock, by Dill, in the 1940s. So how did Jesse’s gang get to Loot Rock in the 1870s? Guides at the cave, at least in the late 1950s when I toured it as a child, explained that the gang swam under the obstructing rock. Some renditions even claimed this was accomplished on horseback. That would mean diving underwater in pitch dark, in a cave that averages sixty degrees, hoping for air (even they could not hope for light) on the other side. Does this make a lot of sense?

Second, the evidence from the cave. Dill claims that he discovered strong boxes from the Gads Hill robbery in the cave near loot rock. There are basically three possibilities here -- the boxes could have been left in the cave by someone else, they could have been left there by the James Gang, or the whole story could have been concocted after the fact. Which was it? Well, I leave you to guess. There is at least one problem, however, with Dill’s explanation. There seems to be a tendency of some storytellers to lose track of distances in Missouri. Most recently even Missouri native Gillian Flynn did this in her best seller Gone Girl, where her central character drives from Hannibal Missouri to Ladue Missouri, a distance of 107 miles each way, for lunch. Similarly, the distance from Gads Hill Missouri to Stanton, where Meramec Caverns is located, is 100 miles. And the James Gang lacked automobiles and interstates. Does it make a lot of sense that a strong box would be carried, presumably unopened, 100 miles or more in the 1870s, and then toted underwater into a dark cave only then to be opened? You can be the judge here.

Second, the evidence from the cave. Dill claims that he discovered strong boxes from the Gads Hill robbery in the cave near loot rock. There are basically three possibilities here -- the boxes could have been left in the cave by someone else, they could have been left there by the James Gang, or the whole story could have been concocted after the fact. Which was it? Well, I leave you to guess. There is at least one problem, however, with Dill’s explanation. There seems to be a tendency of some storytellers to lose track of distances in Missouri. Most recently even Missouri native Gillian Flynn did this in her best seller Gone Girl, where her central character drives from Hannibal Missouri to Ladue Missouri, a distance of 107 miles each way, for lunch. Similarly, the distance from Gads Hill Missouri to Stanton, where Meramec Caverns is located, is 100 miles. And the James Gang lacked automobiles and interstates. Does it make a lot of sense that a strong box would be carried, presumably unopened, 100 miles or more in the 1870s, and then toted underwater into a dark cave only then to be opened? You can be the judge here.

Third, Dill’s own reputation. Lester Dill used to say that he would do “anything” to promote Meramec Caverns. He invented the bumper sticker -- and the only way to avoid having one plastered on your car advertising Meramec Caverns when you visited the cave back in the 1950s was to leave your sun visor down as a signal to the roving parking lot crew. Dill once sent two men dressed as cavemen to the top of the Empire State Building in New York City where they stated they would remain until everyone in the world had visited Meramec Caverns. He engaged in a heated billboard feud with Onondaga Caverns, several miles down the road, as to which was the better cave, without revealing that he in fact also owned Onondaga and that the "feud" was an orchestrated publicity stunt. This is the man who championed the story that Jesse James survived and that he and his gang had used Meramec Caverns as a hideout.

Oh yeah, Dill’s billboards advertising that “competing” cave, Onondaga, which he also owned, proclaimed that Onondaga had been discovered by Daniel Boone. Sound familiar? The State of Missouri now owns Onondaga, so the cave's advertisements are now a bit more restrained. The cave’s website addresses Dill's Daniel Boone claim as follows: “there is no valid source hinting this may be true.”

Oh yeah, Dill’s billboards advertising that “competing” cave, Onondaga, which he also owned, proclaimed that Onondaga had been discovered by Daniel Boone. Sound familiar? The State of Missouri now owns Onondaga, so the cave's advertisements are now a bit more restrained. The cave’s website addresses Dill's Daniel Boone claim as follows: “there is no valid source hinting this may be true.” Members of the James family who were still alive gave no credence to Dalton’s tale and contested his assertions in that Missouri court case. At the conclusion of the trial of that case, during which Dill had unsuccessfully attempted to prove that Frank Dalton was in fact Jesse James, the following statement from Jesse’s daughter-in-law, then still alive but too frail to attend, was read by her lawyer: "Dalton was probably a derelict all his life, and in his waning years he wanted to get a little publicity."

Regardless of who he was or might have been, in that, at least, J. Frank Dalton succeeded. He got his publicity thanks to Lester Dill, Dill's show cave, and a whole lot of signs painted on the roofs of a whole lot of barns along old Route 66.