No, this isn't a post about Jimmy Buffett. But I'll tell you this: the topics of my

SleuthSayers columns come from everywhere--books or stories I've read, movies I've seen, music or news I've heard, other writers I've talked with, etc.--and they're sometimes inspired by the columns written by my fellow bloggers at this site (probably because their ideas are better than mine). I was especially intrigued by some of the recent posts by Michael Bracken, Robert Lopresti, O'Neil De Noux, and others who've been reminiscing about their writing careers, their published works, and the way they'd marketed them. So, piggybacking on that subject, here's a quick look into the past . . .

I've been submitting short stories for publication for almost 25 years--longer than some of my colleagues but not nearly as long as others. Most of my stories have been mysteries, and while my so-called writing career is nothing remarkable, I've been able to reach a few of my goals: several awards, an Edgar nomination, two inclusions in

Best American Mystery Stories, an appearance in Akashik Books' "noir" series, and the publication of half a dozen short-story collections.

I've also had some pretty crazy experiences with regard to submissions, sales, dealing with editors, etc,--but more about that in a minute.

Bio-statistics

As for frequency of publication, my hat's off to several of my fellow

SleuthSayers for their many, many short stories in

AHMM and

EQMM. I'm especially impressed with Robert Lopresti's back-to-back stories in the three most recent issues of

Hitchcock. I'm not yet up there with my heroes regarding the two Dell magazines: I've so far sold 16 stories to

AH and two to

EQ. And only once have I had stories in back-to-back issues of

AHMM: May and June 1999, with a story in their March 1999 issue as well. I did, however, have stories in four consecutive issues of

The Strand Magazine (from June 2016 to Sep 2017)--the

Strand's published 16 of my stories--and after the upcoming issue of

Black Cat Mystery Magazine I will have placed stories in the first three issues of

BCMM. I've also been in the past six issues of

Flash Bang Mysteries, I've had stories chosen for three consecutive Bouchercon anthologies, I've made Otto Penzler's top-50-mysteries list for the past four years, and between 2013 and 2015 I had five stories in the print edition of

The Saturday Evening Post.

Though not primarily a mystery market,

Woman's World has been kind to me as well--last week I sold them my 96th story there--and I've appeared in back-to-back issues of

WW five different times. This is ancient history, but to those of you who remember the pubications, I had 17 stories and 20 poems in

Futures Mysterious Anthology Magazine, 8 stories and 17 poems in

Mystery Time, 19 stories at

Amazon Shorts, and 7 stories in

Reader's Break. Other long-defunct markets that featured my stories include

Murderous Intent,

Orchard Press Mysteries,

Red Herring Mystery Magazine,

Crimestalker Casebook,

Enigma,

Detective Mystery Stories,

Heist Magazine,

The Rex Stout Journal, Desert Voices, Ancient Paths,

Crime & Suspense,

Anterior Fiction Quarterly,

Dogwood Tales, and

The Atlantean Press Review. (We won't talk about how many rejections I've received from the above publications, because I honestly don't know the number--but it's a big one. A lot higher than my number of acceptances.)

One last statistic: my collections of short fiction--

Rainbow's End (2006),

Midnight (2008), Clockwork (2010),

Deception (2013),

Fifty Mysteries (2015),

Dreamland (2016), and

The Barrens (coming in 2018)--contain a total of 240 different stories. As for novels, I've written four of them, all of which I like and two of which are out with an agent, but all of them, alas, remain unpublished. My heart's really in the short stuff.

Welcome surprises

In the icing-on-the-cake department, my story "Molly's Plan," which first appeared in the

Strand, was chosen to be part of The New York Public Library's permanent digital collection, and another of my stories, "The Tenth Floor," was recently included in a 600-page book with 108 different authors from 11 countries, which is up for a Guinnesss World Record for the largest short-story anthology ever published. Several stories of mine have also been published in Braille and on audiotape, taught in high schools and colleges, and translated (last month) in Russia's leading literary journal, although I can't say any of those accomplishments were on my wish list. They were what we at IBM used to call "bluebirds": they just happened to fly in through the open window.

Okay, enough tooting of my own horn. The following is the goofy part of all this:

Weird tales

- Twice I've had stories appear in

Woman's World under someone else's byline. Thankfully

WW paid me and not the other writer, but it's strange to look at one of your own stories in print and see an unfamiliar name beside it. I never did find out whether the dastardly impostor liked my stories or not.

Lesson #1: Once you sell a story and it's out of your hands, anything can happen.

- On three different occasions editors have contacted me asking to buy stories I sent them more than two years earlier. On two of those occasions I happily sold them the stories in question; on the third I had already given up and sold it someplace else. None of those editors ever explained why those submissions were still lingering in their records, and I didn't ask. My wife suspects they just fell behind the piano or the refrigerator and stayed there awhile, as some of our important papers at home tend to do.

- I have twice received acceptance letters for stories that I didn't write. In both cases I contacted the editors and said I wish this were me but it's not.

- I once published a short fantasy story, "Chain Reaction," in

Star Magazine, and proudly appeared alongside accounts of alien kidnappings, Bigfoot sightings, and three-headed chickens.

Lesson #2: If you've been paid, don't worry about it.

- I've had at least a dozen stories accepted by magazines that then promptly (before my stories could be published), went out of business.

See Lesson #1.

- Most of my stories seem to be in the 1000- to 4000-word (short story) range, but my three Derringer Awards were in the short-short, long story, and novelette categories. Yes, I know that doesn't make sense.

- I was once told by an editor that the 12-page story I'd submitted "should have ended on page 7."

- I've published poems in better-known markets like

EQMM,

Writer's Digest,

Grit,

The Lyric, Mobius, Capper's, Byline, Writers' Journal,

Farm & Ranch Living, etc.--BUT I've also published poems in V

olcano Quarterly,

The Pipe Smoker's Epheremis,

Barbaric Yawp,

Hard Row to Hoe, Feh!, The Aardvark Adventurer,

Boots,

Creative Juices,

Appalling Limericks,

Tales of the Talisman, Nutrition Health Review,

Mythic Delirium, Smile,

Hadrosaur Tales,

Outer Darkness,

The Shantytown Anomaly,

Decompositions,

StarLine,

Firm Noncommittal,

ACafeBreak,

The Church Musician Today, The Pegasus Review,

Blind Man's Rainbow,

Krax,

Sophomore Jinx, And many other wild and crazy places. For the record, 31 of my poems appeared in

Rural Heritage, 34 in

Rhyme Time, 47 in

Tucumcari Literary Review, 33 in

Laughter Loaf, and 55 in

Nuthouse. (Did I mention that my poetry is more lighthearted than profound? Bet you would've never guessed.) Anyhow, I challenge you to come up with more creative magazine names than some of those above.

- My short fiction has also appeared in publications with strange (and clever) names:

Champagne Shivers,

Mouth Full of Bullets,

Short Attention Span Mysteries,

Antipodean SF,

Ethereal Gazette,

Illya's Honey,

Simulacrum,

Gathering Storm,

Meet Cute,

Scifantastic,

Fireflies in Fruit Jars, Cenotaph, Thou Shalt Not, D

ream International Quarterly,

Sniplits,

T-Zero,

After Death,

The Norwegian American,

Lost Worlds,

Ficta Fabula,

Just a Moment,

Thirteen,

Lines in the Sand, Phoebe, We've Been Trumped,

Horror Library,

Matilda Ziegler Magazine for the Blind,

Pebbles,

Spring Fantasy,

Eureka Literary Magazine,

Spinetingler,

Trust & Treachery,

Penny Dreadful,

Sweet Tea and Afternoon Tales,

Writer's Block Magazine,

Quakes & Storms,

ReadWriteLearn,

Scavenger's Newsletter,

Nefarious,

Short Stuff for Grownups,

Listen,

The Taj Mahal Review, Mindprints, Inostrannaya Literatura,

Mad Dogs and Moonshine, and

Yellow Sticky Notes.

- Years ago I was about to submit a story to

AHMM, and at the last minute I asked my wife to read it first. She did, and said she thought I should change the ending. I changed it completely, sent it in, and it sold, Later, editor Linda Landrigan told me she bought it because of the ending.

Lesson #3: When your spouse speaks, listen. Especially if she's smarter than you are.

- While most of my short stories are mystery/crime, I've also published 57 westerns, 20 romances, 103 SF/fantasy stories, and 23 "literary"/mainstream stories.

- The second story I sold to

AHMM ("Careers") was less than 1000 words; the third story I sold to them ("Hardison Park") was more than 10,000 words.

- I have twice been paid in advance for short stories not yet written. (That doesn't happen often--at least not to me.)

- One of my stories, "The Early Death of Pinto Bishop," came within two weeks of being filmed. The cast and crew were on board, the screenplay was polished and ready, locations had been arranged, I was told to invite friends to the set, original music had been written for it (I still have the CD), and suddenly everything stopped and everyone went home. Sad but true.

Lesson #4: Don't trust the movie business.

- I once won a $30 gift certificate to Amazon in a contest for 26-word stories whose words had to begin with each letter of the alphabet, in order. My story, called "Misson: Ambushable" was

Assassin Bob Carter deftly eased forward, gun hidden in jacket, keeping low, making not one peep. Quietly Robert said, to unaware victim: "Welcome. Xpected you." ZAP. (Hey, what did you expect, in 26 words? Fine literature?)

- I've never published a story written in present tense. I don't mind reading them, but when it comes to my own writing, I guess I prefer the old "once upon a time" approach.

- One of my stories, "A Thousand Words" (

Pleiades), has been reprinted seven times; two other stories, "Newton's Law" (

Reader's Break) and "Saving Mrs. Hapwell" (

Dogwood Tales Magazine), have been reprinted six times each; and at least four of my stories have been reprinted five times each.

Lesson #5: Recycle.

- I once sent the same story to two different publications at the same time, then sent another story to two other publications as the same time. As it turned out, one of the two places I'd sent the first story accepted it, and one of the two places I'd sent the second story accepted that one. So all was well; I just sent withdrawal letters to the two markets that hadn't yet responded. BUT it made me think: What if both those first two places had wanted that first story, or if both the second two places had wanted the second one? I would've had to withdraw an already accepted story, which isn't the best way to get on an editor's good side. This is not really a lesson because everyone's mileage will vary, but ever since that time, I've been reluctant to simultaneously submit my work.

- My payment for one of my early story sales was a lifetime subscription to the magazine.

- When my publisher (Joe Lee, of Dogwood Press) and I were having trouble coming up with a title for my fourth collection of short fiction (Joe has usually given those books the same title as one of the included stories), we solved the problem this way: we changed the name of an as-yet-unpublished story to "Deception," included it in the collection, and made that the title of the book as well.

Lesson #6: Think outside the book-box.

- One of my stories in the

Strand ("Bennigan's Key," 5000 words) featured only one character and had no dialogue.

- My longest published short story ("Denny's Mountain,"

Amazon Shorts) was 18,000 words. My shortest ("Mum's the Word,"

Flashshots) was 55 words.

- At our local Kroger store, I once went through the checkout line with three copies of a magazine that contained one of my mystery stories. The checker said, around a wad of chewing gum, "You got three of these." I told her I knew that. "But they're three of the same issue," she said. "I know," I replied. "Actually"--I stood up a little straighter and lifted my chin--"I have a story in this issue." She gave me a long, blank look and said, "That'll be $4.80."

Lesson #7: You're probably not as big a deal as you think you are.

- One of my stories, "The Garden Club," was written start-to-finish between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. in a room at the Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Francisco, after I woke up sick and feverish and couldn't get back to sleep. I submitted it as soon as I got home from the trip, and the first editor I sent it to bought it. In the acceptance letter she said it had the best ending she and her staff had read in twenty years.

- A producer who was planning to film one of my stories called me and said he needed a logline for it, for marketing purposes. I said I didn't know what a logline was. He told me to find and read an old copy of

TV Guide, and hung up. I found a copy in a back closet, and one of the entries said something like "Little Joe confesses to Hoss and Adam that he's fallen in love with an Indian girl." Understanding dawned, and I came up with what I thought was an effective logline. The producer even liked it. But the movie never got made.

See Lesson #4.

- I once sold a story called "Wheels of Fortune" to an Australian magazine that published only on CD-ROM, and was required to read my story aloud and send it to them as a recording. I still have the magazine-on-CD that they later mailed to me, but I have never listened to my story.

- After my first submission to the

Strand (the story was "The Proposal," the first one I ever sold them), editor Andrew Gulli phoned me and said he liked the story, but his staff was unfamiliar with the kind of poison I had used. I told him that was because it wasn't real--I made it up. He paused just long enough to really scare me, then said, "Okay."

Lesson #8: If something in your story just won't work, invent something that will.

- More than 90% of my published stories were written in third-person POV.

- I appeared in every issue of the magazine

Mystery Time from 1994 until its demise in 2002 (17 issues).

- One of my short stories was rejected almost two dozen times. I later heard that a national magazine was looking for Christmas stories, so I changed the setting of my oft-rejected story from summer to winter, included gloves and icicles and Christmas lights and gifts and carols, and sold it for much more than I would've made at any of the previously-attempted markets.

Lesson #9: Don't give up.

And that's that. If you would, let me know about some of your own strange experiences, in dealing with editors or writing stories or novels or marketing them. What are some of the most unusual or notable things you've had happen to you, as a writer?

Lesson #10 (to myself): Don't write such a long column, next time . . .

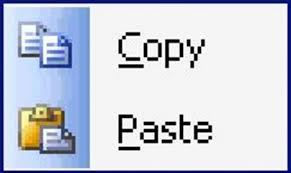

1. Everyone knows about using the keyboard to copy/cut/paste (Ctrl-C, Ctrl-X, Ctrl-V)--but did you know that you can do a "select all" with the shortcut Ctrl-A? Also, if you make a mistake you can undo it without using the dropdown command menu. Just use Ctrl-Z. It'll even back you up more than one occurrence. Hit Ctrl-Z several times, and it'll take you back to whatever previous point you want, repairing missteps as you go. This saved me recently when I was trying to delete a word in a looooooong email I had saved as a draft, and when I hit the delete key my computer thought I was trying to delete the entire email. I wasn't, but it did. I almost panicked, and said some unkind words, and then realized I could hit Ctrl-Z and bring the email back from the ashes. (By the way, for Apple users, the Command key is used instead of Ctrl.)

1. Everyone knows about using the keyboard to copy/cut/paste (Ctrl-C, Ctrl-X, Ctrl-V)--but did you know that you can do a "select all" with the shortcut Ctrl-A? Also, if you make a mistake you can undo it without using the dropdown command menu. Just use Ctrl-Z. It'll even back you up more than one occurrence. Hit Ctrl-Z several times, and it'll take you back to whatever previous point you want, repairing missteps as you go. This saved me recently when I was trying to delete a word in a looooooong email I had saved as a draft, and when I hit the delete key my computer thought I was trying to delete the entire email. I wasn't, but it did. I almost panicked, and said some unkind words, and then realized I could hit Ctrl-Z and bring the email back from the ashes. (By the way, for Apple users, the Command key is used instead of Ctrl.) 5. What's the best way to copy/paste a manuscript into the body of an email? If a market requires the submission of a manuscript as a part of the email rather than as an attachment, it can be hard to paste the story directly into the body of the email without gorking up the spacing and formatting. Here's a good way to do that without risk: save the manuscript first as a plain-text (.txt) file in your Word program, then close it and open it again, and then paste it into your email. It will now be formatted correctly. NOTE: As I mentioned in my post last week, saving a regular manuscript in plain-text will convert everything to Courier 10-point font whether you want it to or not, and will lose any special features like italics and underlining. Emphasized text can be indicated, however, by typing an underscore (_) immediately before and after any text (letter, word, phrase, whatever) that should've been italicized or underlined. If by chance you save it as .txt and it doesn't convert it to 10-point Courier (this sometimes happens, for some reason), you're still okay--just remember that your special characters are still lost, and you'll still need to substitute the underscores.

5. What's the best way to copy/paste a manuscript into the body of an email? If a market requires the submission of a manuscript as a part of the email rather than as an attachment, it can be hard to paste the story directly into the body of the email without gorking up the spacing and formatting. Here's a good way to do that without risk: save the manuscript first as a plain-text (.txt) file in your Word program, then close it and open it again, and then paste it into your email. It will now be formatted correctly. NOTE: As I mentioned in my post last week, saving a regular manuscript in plain-text will convert everything to Courier 10-point font whether you want it to or not, and will lose any special features like italics and underlining. Emphasized text can be indicated, however, by typing an underscore (_) immediately before and after any text (letter, word, phrase, whatever) that should've been italicized or underlined. If by chance you save it as .txt and it doesn't convert it to 10-point Courier (this sometimes happens, for some reason), you're still okay--just remember that your special characters are still lost, and you'll still need to substitute the underscores.