by John M. Floyd

Over the past few weeks, I've finished three mystery-writing projects: a 7500-word short story, a 110-page screenplay, and a 90,000-word collection of thirty of my stories. The short story will be submitted soon to one of the mystery magazines, the collection is scheduled to be released by my publisher next year, and the screenplay will probably be used to prop up a table leg--but all three were great fun to put together. What wasn't fun was proofreading my late-to-final drafts. I tend to make silly mistakes when I write, and the sheer volume of those mistakes gave me the idea for this column, which will probably contain even more mistakes. Believe me, I try to find and correct these before they go out into the world, but still . . .

Thorns in my side

Here are some writing errors (some minor, some not-so) that show up a lot in my fiction manuscripts:

Pet phrases. For some reason I apparently enjoy writing things like "she narrowed her eyes," "he scratched his chin," "she plopped into a chair," "his face darkened," etc.--there are a couple dozen of these--and I find myself using them over and over. Why? Who knows. My characters also seem to like sighing, staring, shrugging, and turning. Especially turning. They turn and leave, turn to reply, turn and look out the window, turn to answer the phone, and so on. It's the kind of repetition that annoys me when I discover it in my drafts, and if I left it in it would certainly annoy editors and readers. (Actually, if it bothers the editors it'll never get a

chance to bother the readers.)

Overuse of dashes.

Overuse of dashes. I love dashes. Maybe because it's hard to use one improperly: under the right conditions they can be substituted for semicolons, colons, parentheses, and almost anything else. I use them often for asides--like this--and I also like the notion of "interrupted speech" (because real people interrupt each other all the time when they talk), and dashes are an effective sentence-ending way to indicate that. Even so, too much of anything is not a good thing.

Cliches. Boy do I like cliches. My excuse, I think, is that I use so many in real life it's only natural to want to put them into my writing as well. But if it's not in dialogue, a cliche probably doesn't belong in the story. When/if I come to my senses, I try to locate them and weed them out.

Backward apostrophes. This error occurs only when using certain fonts, but in Times New Roman, an apostrophe before something like em (Round 'em up and cuff 'em) winds up turned in the wrong direction--which looks ridiculous. To correct it, I type a letter immediately before it, then put in the apostrophe, then delete the preceding letter. A good way to remember it: type th'em and then delete the "th."

Too many combined words.

Too many combined words. This is something else I love, probably because it speeds up the pace. Examples: doublecheck, halfwit, ballplayer, dumptruck, kindhearted, mothership, workboots, overanalyze, mumbojumbo, coattails, thunderclap--and especially when they're used as adjectives, like smalltown politics or livingroom furniture or quartermile run. But I have to be careful not to do it when it

really shouldn't be done (bluejeans, divingboard, machinegunfire, etc.). Being innovative goes only so far.

Extra spaces between words. This is pure carelessness. They're hard to catch, and they're distracting if you don't. If, for instance, you prefer to put only one space after a period, you should be consistent and do it every time.

Repetition. Especially in early drafts, I repeat so many things it's hard to believe: ideas, words, phrases (see "pet phrases," above), even locations and character names. In my defense, I think some of this comes from trying to make things extremely clear to the reader--but the truth is, today's readers are smart enough not to require everything spelled out for them in detail, or--to use another cliche--to have writers beat them over the head with something in order for them to understand it. Cutting out repetition is a large part of my self-editing process. It becomes even more important when putting previously published stores together in a collection, because those stories, when first written, weren't expected to ever be read back-to-back with other stories.

Omitted quotation marks (usually close quotes). More carelessness.

Using a for an, and vice versa. Why do I encounter this so often in late drafts, since I truly do know when to use one and when to use the other? Probably because I've gone back and changed things in the manuscript, and when I happen to change a noun that doesn't begin with a vowel sound to one that does, etc., I might've unintentionally created an "a vs. an" error.

Thorn removals

Some of the missteps I seem to have gotten better at avoiding, over the years:

Overuse of semicolons. I think semicolons are a great way to divide two complete sentences that are too closely related to be separated by the finality of a period. But semicolons do look a bit formal in genre fiction (certainly in dialogue), and too many of them can be distracting. These days, I go through my manuscripts-in-progress and try to turn most of my semicoloned sentences into two separate sentences, or add a "comma followed by an and," or substitute one of those overused dashes. But--just shoot me--I still like semicolons.

Too many "ly" adverbs.

Too many "ly" adverbs. There's always been a difference of opinion as to whether this is even a problem, but most writers agree that it's better to use stronger verbs than to have to prop them up with modifiers.

Too many back-and-forth lines of dialogue without identifying the speaker. The reason I don't commit this error as often as I used to, I think, is that it irritates me so to find it in stories/books that I read. Nothing is more maddening to a reader than having to count lines backward to find out who's saying what.

Too many italics. Thank God I'm finally beginning to bring this weakness under control. You don't always need to put emphasis on a word, or italicize an unspoken thought; sometimes it's obvious from the way the sentence or paragraph is written. (Oh no, she thought, flattening her back against the wall. Did anyone see me?)

Overuse of ellipses. Unless you're hesitating . . . and even if you are . . . too many of these can become bothersome.

Unnecessary exclamation points. I almost never use an exclamation point anymore. When I do, it's in dialogue, and it has to be something like Your socks are on fire! or Look out, it's a werewolf!

Overuse of dialect. There's a fine line here. Some writers feel that any use of dialect is overuse. I maintain that using too many misspelled words to convey dialect can be a mistake. Sho nuff.

POV switches. These still sneak through at times, especially in stories with third-person-limited viewpoint. (Example: Judy looked at him, and her face turned red. If we're in Judy's POV, she can't see her own face turn red, even though she might "feel her face grow warm.") Other switches might include, in a third-person-multiple story, two characters having a conversation and jumping from one's POV to the other's too abruptly, without something like a scene break in between.

Afterthoughts

Not that it matters, but here are some things I find fairly easy to write, probably because I like them so much: dialogue, humor, plot twists, weird characters, action scenes, and surprise endings.

Things I find hard to write, probably because I don't like them much: descriptions of people and places, backstory, exposition, unspoken thoughts, flashbacks, and symbolism. I realize how necessary these can be, and I hope I'm getting better at them, but for me they require a lot of effort.

What are your strengths and weaknesses, likes and dislikes? What are some writing errors that constantly seem to find their way into your stories and novels even though you know better? Which ones bother you the most when you encounter them in the writing of others?

Whatever they are, here's to better mysteries and fewer (mys?)steps. For all of us.

1. The Salvation (2014) -- This is an action-packed, revenge-driven movie filmed in (believe it or not) South Africa, and starring actors from France, England, Wales, Sweden, Scotland, the U.S., South Africa, Germany, and Spain. Last but not least, the director, lead actor, and most of the crew were all from Denmark. Featured are Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Sir Jonathan Pryce, and an extremely spooky Eva Green. Directed by Kristian Levring.

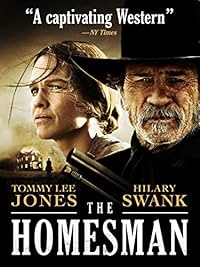

1. The Salvation (2014) -- This is an action-packed, revenge-driven movie filmed in (believe it or not) South Africa, and starring actors from France, England, Wales, Sweden, Scotland, the U.S., South Africa, Germany, and Spain. Last but not least, the director, lead actor, and most of the crew were all from Denmark. Featured are Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Sir Jonathan Pryce, and an extremely spooky Eva Green. Directed by Kristian Levring. 4. The Homesman (2014) -- If there is such a thing, this is a "literary" Western. A great performance by Tommy Lee Jones, as a drifter rescued from the hangman's noose by pious widow Hilary Swank and then hired to escort her and a wagonload of insane women to an institution run by, of all people, Meryl Streep. (How could this movie not be good?) Jones also directed and co-wrote. Filmed in New Mexico.

4. The Homesman (2014) -- If there is such a thing, this is a "literary" Western. A great performance by Tommy Lee Jones, as a drifter rescued from the hangman's noose by pious widow Hilary Swank and then hired to escort her and a wagonload of insane women to an institution run by, of all people, Meryl Streep. (How could this movie not be good?) Jones also directed and co-wrote. Filmed in New Mexico.