It's Derringer time, and that's prompted me to think about the whole literary jury process. I've been on several, and this guest post below, by my good friend and author Jayne Barnard, really speaks to me. How about you? Have you ever been on a literary jury? Please tell us your experience in the comments below.

We, the Jury...

by J.E. Barnard

When a crime writer hears the 'J' word, they can be forgiven for thinking Twelve Angry Men, A Jury of Her Peers, or any book, movie, or news article about a trial. Maybe our minds veer to Grisham novels about juries or the Richard Jury mysteries by Martha Grimes. Rarely do we consider the other kind of jury: the one that decides on a writers' award. Whether it's the National Book award, the Giller Prize, the Governor General's Award, the CBC or Writers Trust, or--particular favourites of crime writers--the Edgars, Agathas, Daggers. Derringers, Theakston's Old Peculiar, and Canada's own Crime-writing Awards of Excellence (formerly the Arthur Ellis Awards,) there's a jury behind it.

After two decades of serving on writers' juries in the Canada and the USA, for fiction and non-fiction, children and adults, short fiction and long, even for plays and scripts, I've got some thoughts to share about what makes a good juror and why writers would, indeed should, try jury work at least once in their literary career.

Who sits on a writers' award jury?

The fact is, juries are made up mainly of readers and writers like you. Award-winning authors, multi-series authors, one-book authors, true crime authors, short story authors, journalists, bloggers, reviewers. Other seats are filled by those working in the publishing industry, or in libraries, or those with subject area experience like lawyers, prosecutors, criminologists, pathologists, cops. But mainly writers and readers.

What makes a good crime writing juror?

1. Someone who loves crime writing. Writing it, reading it, listening to it, watching it.

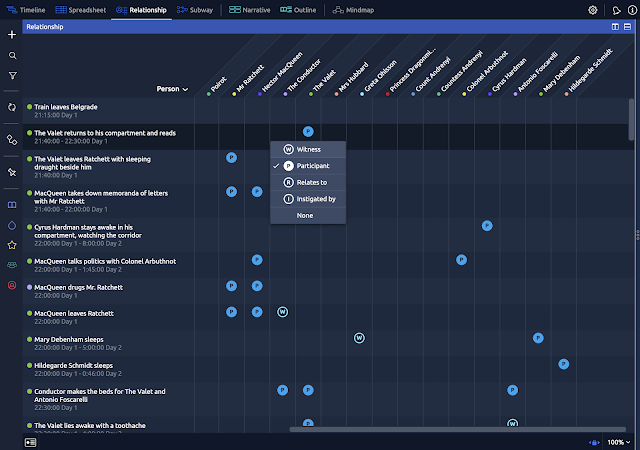

That juror represents all readers of that crime category. Ideally, they're aware of what's hot in crime writing and tropes that are past their prime. The good juror accepts that, as much as they personally may love the Golden Age detective authors like Agatha Christie and Dashell Hammett, the genre has moved on, and the awards moved on with it. The good juror knows that even though they personally love cozy cat mysteries with recipes or serial killer POV scenes in alternating gory chapters, the genre is far wider than both and they must evaluate all entries in their category not on what they personally prefer but on how well the author has executed a work according to its place on the crime writing spectrum.

2. Collaboration. This essential qualification is too often left unstated. It's rare that a single book or story rises to the top of every jury member's list. Any category may include several eminently worthy candidates for the top slot. Jurors need to communicate their shortlist selections clearly to fellow jurors and be able to defend those choices with calm, clear language, while respecting other jurors' alternative perspectives. Only together can jurors develop a short list that reflects the breadth of excellence in that category of writing.

Other qualifications: your writing credentials and your relevant life experience. A working children's librarian or elementary school teacher is better placed to evaluate a Children's and Young Adult category than, say, a retired criminology professor who taught adults and has no regular contact with child and adolescent readers. It's not that the latter couldn't evaluate the writing and the structure, but that they're unfamiliar with what readers in that category are currently consuming and what those readers value in a book or story.

What other qualities does a good juror bring?

Ideally, they're familiar with:

- the award's writing language (in Canada, so far, that means English or French) including a solid grasp of grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

- structural issues of storytelling: plotting, pacing, tension.

- elements of a strong opening and a powerful ending.

Good jurors understand enough about characters and their arcs to tell whether they're introduced or developed poorly or well, and can explain those thoughts to their fellow jurors during the consultation process (and to the author if their jury is one that offers comments/feedback.)

Non-fiction jurors ideally have a grasp of language and storytelling as well as some subject-area expertise.

One reason why juries traditionally have three or more members is to balance overall strengths. A strong writer with two subject experts, or two writers with a lone subject expert, can turn in the strongest possible shortlist if they respect the knowledge and skills each member brings to the reading and discussion process.

Why serve on a jury?

1. To give back to the community of writers that breaks trail, nurtures your skills, and has built the publishing industry and awards processes you already are or hope soon to be competing in.

2. As a master class in what makes some stories, articles or books work better (and win awards) than others.

Trust me on the second one: jury work can revolutionize your writing practice. There are few more concentrated ways to figure out what makes a good first page than by reading twenty or more of them in quick succession to see which ones hold your attention and figure out what makes them stand out. Read twenty opening chapters and you'll have a clearer idea what kind of character introductions, settings, or situations work best - or utterly fail - to pull you into stories you might not otherwise read. Look at twenty endings and some will have a resonance you can feel to your bones while others will be just okay. Take those new or more in-depth understandings and apply them to your own writing, and your odds of seeing your work on an awards shortlist can increase exponentially.

I hope the next time a crime writing award puts out a public or selective call for award jurors, you'll take a moment to consider whether you have some skills, dedication, and desire to learn and to serve. And then apply.

Alberta author J.E. (Jayne) Barnard has two award-winning series – The Maddie Hatter Adventures and The Falls Mysteries – and numerous short

stories involving history, mystery, crime, and punishment. Between writing gigs,

she volunteers for Sisters in Crime and Crime Writers of Canada, and regularly serves

on fiction juries in Canada and the USA. She lives in a vine-covered cottage

between two rivers, keeping cats and secrets. Her most recent winter mystery is

Where the Ice Falls (Dundurn Press 2019). Find her on your favourite platform via Linktree

https://linktr.ee/je_barnard