Seriously, these were all the standard medical treatment from ca 200 AD until the first use of antibiotics in the 1940s. Nostalgia isn't what it's cracked up to be. The truth is, standard medical practice between those dates probably killed more people than all the wars in history. And it certainly makes for some interesting possibilities as far as historical murder, because how would you tell a homicide from a treatment?

The reason bleeding, sweating, and purging caught on was because of Galen, the most famous Greek physician of the Roman empire. A legend in his own time, his writings survived the wholesale wreckage of ancient books and learning of the Dark Ages: they were the major source of medical information for Byzantium and the Arabic Abassid Dynasty, and got reintroduced to the West in the 11th century as part of the treasures that the Crusaders brought / sent back to Western Europe. His influence was so great that, when 13th century anatomists found differences between, er, actual anatomy and Galen's theories, they explained that the human body had obviously changed since the ancient world...

Anyway, Galen practiced medicine by humors, which has nothing to do with jokes. According to this theory (which probably started back in ancient Egypt), humans are divided into four types:

|

| 18th c. woodcut - Wikipedia |

- Sanguine (enthusiastic, active, and social) - ruled by their blood, which Galen believed was manufactured in the liver. Element, air; season, spring, infancy - warm and moist

- Choleric (short-tempered, fast, or irritable) - ruled by yellow bile, which came from the spleen. Element, fire; season, summer, youth - warm and dry

- Melancholic (analytical, wise, and quiet) - ruled by black bile from the gallbladder. Element, earth; season, autumn, adulthood - cold and dry

- Phlegmatic (relaxed and peaceful) - ruled by phlegm, made in the brain/lungs. Element, water; season, winter, old age - cold and wet

(There were also astrological aspects to all of this).

Anyway, all your ills, moods, "humors", etc., were based on an imbalance of the blood, bile, phlegm. So the obvious thing to do was the cleanse you so that your body could rebalance. (A lot like the eternal craze for juice fasts, fad diets, and high colonics...) Thus, bleeding, sweating, and purging.

Folks, all I can say is that we are living in the best time to be ill in history. Back during the plague years, one physician infamously said, bleeding patient after patient, "Plague, I will cure you by bleeding!" All the patients died, but he soldiered on, knowing that eventually it would work. And doctors continued on the same path until very modern times. Louis XIV's oldest son, the Grand Dauphin, grandson (the Duke of Burgundy), and his wife, the Duchess, and their oldest son, the Duke of Brittany, all died within a year and a half because their doctor tried to cure smallpox and measles with bleeding. The result was that two entire generations of the royal family were wiped out and the future Louis XV became the Dauphin at the ripe age of five. (This was, in case, you don't know it, a disaster: "Apres moi, le deluge".)

Throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th century, heart attack patients were bled; young girls suffering from "green sickness" were either bled or advised to have sex; Marianne Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility was bled when she obviously had pneumonia. And, aside from illness, it was largely believed that everyone should be bled regularly, to help balance their humors: monks and nuns were bled about four times a year. The only real change over the centuries was that, instead of using leeches, doctors actually performed a phlebotmy using special lancets or knives.

By the 19th century, "One British medical text recommended bloodletting for acne, asthma, cancer, cholera, coma, convulsions, diabetes, epilepsy, gangrene, gout, herpes, indigestion, insanity, jaundice, leprosy, ophthalmia, plague, pneumonia, scurvy, smallpox, stroke, tetanus, tuberculosis, and for some one hundred other diseases. Bloodletting was even used to treat most forms of hemorrhaging such as nosebleed, excessive menstruation, or hemorrhoidal bleeding. Before surgery or at the onset of childbirth, blood was removed to prevent inflammation. Before amputation, it was customary to remove a quantity of blood equal to the amount believed to circulate in the limb that was to be removed." (Wikipedia, Bloodletting)

Throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th century, heart attack patients were bled; young girls suffering from "green sickness" were either bled or advised to have sex; Marianne Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility was bled when she obviously had pneumonia. And, aside from illness, it was largely believed that everyone should be bled regularly, to help balance their humors: monks and nuns were bled about four times a year. The only real change over the centuries was that, instead of using leeches, doctors actually performed a phlebotmy using special lancets or knives.

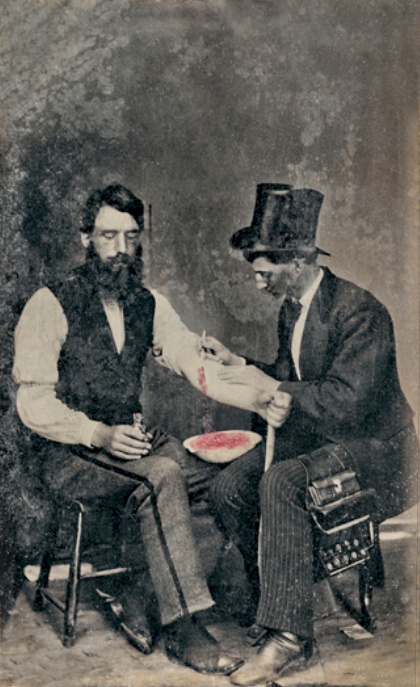

|

| Photo of Bloodletting in 1860 - Wikipedia |

There are fewer references to sweating than to bleeding. The main one I can think of is in Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder, where a naughty little boy gets stung by a whole nest of wasps, and is slathered with mud, and bound up in sheets and left to sweat the poison out. It apparently worked, because he survived. When I was a child, if I had a fever, I had blankets piled up on top of me to make the fever break by sweating it out. And, of course, sweat lodges, hammams, and saunas all operate on the theory of making you sweat, thereby cleansing you, both inside and out.

And purging is everywhere in the literature, from diaries to novels. My mother, born in 1917, believed that in spring you need to eat purging foods and/or take a thorough laxative to cleanse the body. In Jack Larkin's invaluable The Reshaping of Everyday Life 1790-1840, he describes a world of hard work, much fun, and horrifying medicine. "Bleeding and blistering, purging and puking" were the standard remedies for EVERYTHING. And they were the kind of thing that your average frontier citizen in America could do at home, for themselves, using plants, herbs and (sometimes) kerosene. (No, I am not kidding.) Thus when Zadoc Long's wife suffered what was probably a nasty gallbladder attack, he gave her a strong emetic made of thoroughwort to "puke her". (88-92)

What about medicine? Well, there wasn't much. Quinine did work on malaria, but it was also given for almost any "ague", or recurring fever. One of the most widely used drugs was calomel, mercurous chloride, which was used for such things as syphilis and yellow fever. It didn't cure either of them, but it gave wonderful proof that it was strong medicine: mercury [poisoning] made people salivate like a mad dog, then lose their teeth, and perhaps their hair. A thorough purging indeed. And let us not forget alcohol. Whenever you read in the literature about someone being given "cordials" that is some form of alcohol. A lot of people died in a prescribed drunk. Supposedly Oscar Wilde, being prescribed champagne on his deathbed, said, "I am dying as I have lived, above my means".

There were a few things that worked: As I mentioned in a previous blog ("Arsenic and Old Lace") there was opium in its various forms, especially laudanum (alcohol and opium combined - the pause that refreshes and the mother's friend). Cocaine was used as a numbing agent, a stimulate, and even, apparently as a cure for dandruff. There was an effective smallpox inoculation, using live disease material. This was risky, because many patients got smallpox from the inoculation, and some died. Even more effective was Dr. Jenner's vaccination using cowpox, which ran far less risk of infection and death. While smallpox was never eradicated (not enough people were either able to get the vaccination or were willing to run the risks), at least it became rarer.

There were a few things that worked: As I mentioned in a previous blog ("Arsenic and Old Lace") there was opium in its various forms, especially laudanum (alcohol and opium combined - the pause that refreshes and the mother's friend). Cocaine was used as a numbing agent, a stimulate, and even, apparently as a cure for dandruff. There was an effective smallpox inoculation, using live disease material. This was risky, because many patients got smallpox from the inoculation, and some died. Even more effective was Dr. Jenner's vaccination using cowpox, which ran far less risk of infection and death. While smallpox was never eradicated (not enough people were either able to get the vaccination or were willing to run the risks), at least it became rarer.

Basically, before 1945, the best thing to do for your health was to choose your parents wisely. And not get in accidents, wars, or be pregnant. If you could survive birth, infancy, early childhood (all of which wiped out about 50% of the population), and then could manage to not die in accidents (a simple scratch could give you blood poisoning or tetanus), childbirth, epidemics or war, you could become very, very old. And be remarkably healthy the whole time. Eleanor of Aquitaine had 10 children, a complex and busy life, and still managed to live active and healthy until she was 82. The philosopher Fontenelle (1657-1757) was known for his intellect and his womanizing. (He said to Madame Helvetius, when he met her in his late 90s, "Ah Madame, if only I were eighty again!") A medieval letter from a visiting priest to an abbey offered birthday wishes to Brother Narcissus, on the occasion of his 116th birthday.

Good genes? Undoubtedly. And darned little bleeding, sweating, or purging.

And purging is everywhere in the literature, from diaries to novels. My mother, born in 1917, believed that in spring you need to eat purging foods and/or take a thorough laxative to cleanse the body. In Jack Larkin's invaluable The Reshaping of Everyday Life 1790-1840, he describes a world of hard work, much fun, and horrifying medicine. "Bleeding and blistering, purging and puking" were the standard remedies for EVERYTHING. And they were the kind of thing that your average frontier citizen in America could do at home, for themselves, using plants, herbs and (sometimes) kerosene. (No, I am not kidding.) Thus when Zadoc Long's wife suffered what was probably a nasty gallbladder attack, he gave her a strong emetic made of thoroughwort to "puke her". (88-92)

What about medicine? Well, there wasn't much. Quinine did work on malaria, but it was also given for almost any "ague", or recurring fever. One of the most widely used drugs was calomel, mercurous chloride, which was used for such things as syphilis and yellow fever. It didn't cure either of them, but it gave wonderful proof that it was strong medicine: mercury [poisoning] made people salivate like a mad dog, then lose their teeth, and perhaps their hair. A thorough purging indeed. And let us not forget alcohol. Whenever you read in the literature about someone being given "cordials" that is some form of alcohol. A lot of people died in a prescribed drunk. Supposedly Oscar Wilde, being prescribed champagne on his deathbed, said, "I am dying as I have lived, above my means".

There were a few things that worked: As I mentioned in a previous blog ("Arsenic and Old Lace") there was opium in its various forms, especially laudanum (alcohol and opium combined - the pause that refreshes and the mother's friend). Cocaine was used as a numbing agent, a stimulate, and even, apparently as a cure for dandruff. There was an effective smallpox inoculation, using live disease material. This was risky, because many patients got smallpox from the inoculation, and some died. Even more effective was Dr. Jenner's vaccination using cowpox, which ran far less risk of infection and death. While smallpox was never eradicated (not enough people were either able to get the vaccination or were willing to run the risks), at least it became rarer.

There were a few things that worked: As I mentioned in a previous blog ("Arsenic and Old Lace") there was opium in its various forms, especially laudanum (alcohol and opium combined - the pause that refreshes and the mother's friend). Cocaine was used as a numbing agent, a stimulate, and even, apparently as a cure for dandruff. There was an effective smallpox inoculation, using live disease material. This was risky, because many patients got smallpox from the inoculation, and some died. Even more effective was Dr. Jenner's vaccination using cowpox, which ran far less risk of infection and death. While smallpox was never eradicated (not enough people were either able to get the vaccination or were willing to run the risks), at least it became rarer. Basically, before 1945, the best thing to do for your health was to choose your parents wisely. And not get in accidents, wars, or be pregnant. If you could survive birth, infancy, early childhood (all of which wiped out about 50% of the population), and then could manage to not die in accidents (a simple scratch could give you blood poisoning or tetanus), childbirth, epidemics or war, you could become very, very old. And be remarkably healthy the whole time. Eleanor of Aquitaine had 10 children, a complex and busy life, and still managed to live active and healthy until she was 82. The philosopher Fontenelle (1657-1757) was known for his intellect and his womanizing. (He said to Madame Helvetius, when he met her in his late 90s, "Ah Madame, if only I were eighty again!") A medieval letter from a visiting priest to an abbey offered birthday wishes to Brother Narcissus, on the occasion of his 116th birthday.

Good genes? Undoubtedly. And darned little bleeding, sweating, or purging.

Death and Texas

Death and Texas