05 January 2026

What Happened to Living Forever?

Everyone knows the young believe they're going to live forever. Why else do they take the risks they do? The moment teens age out of supervision by adults, many of them drive recklessly, drink to excess, experiment with drugs, try extreme sports, hook up with strangers, and otherwise play Russian roulette with their lives, convinced they'll be the lucky ones who'll always beat the odds and dodge the consequences. As we get older, our beliefs about our own vulnerability to death diverge, depending on a number of factors. As a healthy middle class American from a family that took few risks and had a genetic predisposition to longevity on both sides, I have lived my whole adult life confident that death wasn't coming for me any time soon—in other words, believing that I would live forever.

I was born a couple of years before the Boomer generation, and the world has changed by three paradigm shifts (if you count the one in progress) in my lifetime. As an octogenarian, I no longer say "forever." I tell my dental hygienist, "These teeth have to last another twenty years." I tell my husband, "If I live to be 100, let's go to Paris on my birthday." However, it's no longer up to me, ie how my body, mind, and DNA weather time. For me to live my full span, a couple of other things have to beat the odds. The planet has to refrain from falling apart or boiling over. The human race has to refrain from blowing itself to oblivion. I'm not as concerned for myself as my younger self would have been, having had one helluva run till now. The worst is that time needs to keep rolling out long enough to accommodate my hostages to fortune—my granddaughters.

Here are three poems from my new poetry collection, The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle, that speak to this concern. "Once Upon A Time" and "Dissonance" first appeared in Yellow Mama.

If The Plot Unravels

in 1654 the Montaukett warriors met

at the highest point of the bluff

the Naragansetts won the battle

the Montauketts were defeated

they had already sold land to the settlers

their way of life was about to unravel

today a great boulder marks where they met

Council Rock overlooks the ocean

it anchors Fort Hill Cemetery

a municipal burying ground

where all the dead are welcome

founded thirty years ago, when we

had just acquired our crumb of Hamptons heaven

and were looking for accommodations after death

no graves had yet been dug when we first visited

we walked hand in hand over the wild hill

admired the Rock and the ocean view

joked about how this six-foot double decker bed

was the classiest real estate we’d ever own

later, I wrote a poem about that day, a love poem

it felt like permanence

now the planet is unraveling

the Montauk Point Lighthouse, built

three hundred feet from the cliff’s edge

now stands only one hundred feet

from tumbling onto the rocks below

having reached an age that visits doctors and reads obits

we wonder if our plot will be there when we need it

or by then have fallen to earthquake or tsunami

wildfire or flood, some implacable disaster

one of the many that unspool, relentless

now the world’s no longer tightly wrapped

riding in the limo to my father’s funeral

I heard Aunt Hilda dither: if she sold the country house

should she dig up Uncle Bud’s ashes or leave them in the garden

that’s when I vowed I’d never be cremated

on top of all the movie sight gags, it was the last straw

but the last two in-ground plots in Manhattan went

in 2015 for $350,000, and in 2023 a single grave

in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood runs as high as $26,000

so if Fort Hill is swept away or crumbles into the sea

and the $750 plot in Montauk is a write-off

you might as well send me up in flames

with the rest of the planet, sere as dune grass

ready for a conflagration we can’t stop

Once Upon A Time

once upon a time I walked through Timbuktu

city of sand, its hushed streets sifted fine, its buildings

rounded like sandcastles shaped by tidal winds

long before terrorists destroyed what I remember

passing Tuareg draped in indigo

I watched them drift beside their camels

toward the desert, the stone well and leather bucket

the salt mines that lie beyond the sunset

once upon a time I spent a week in Lahaina

before the fire consumed it, I remember

wearing a white tuberose lei, hearing laughter

the breeze carrying music and the scent of food

sunset tinting the water, slate blue mountains rising

not far from shore, humpback whales and their young

once upon a time I climbed the tower of Nôtre Dame

ancient stone rose into darkness all around me

my young knees made nothing of the winding stair

or if I breathed a little faster at the top

it was worth it to say salut to the gargoyles

and stick out my tongue at Paris

once upon a time in Côte d'Ivoire, in Bouaké

when independence was long fought for, newly won

before the civil war, before the hate and anger

when nobody had a television and the nights

were for drinking and dancing, oh, the dancing

for two years I always fell asleep at night

to talking drums in every courtyard

all across the city chanting lullaby

it's not looking like much of a happily ever after

this grumbling planet is exhausted

me, I'm glad I had my once upon a time

now I'd like to ask for a generation longer

until my granddaughters have had their time

squeezed joy to the last sweet drop

embraced love and laughter and adventure

why is it so hard to hold back the fire and flood

that's been baying for release since they were born

Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological phenomenon that occurs

when a person holds two contradictory beliefs at the same time.

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326738

if they'd only leave us in peace

how we'd relish our longevity

our gift for the unmeasured moment

the giant tortoise, the African elephant

the koi with its splashes of sunset red and gold

and humanity, the genetic booby prize

our extra burden, values and beliefs

responsibilities and ambiguities

who holds as few as two beliefs?

what two values fail to contradict each other?

the dissonance of my choices every day

would crush me if I didn’t push

with all my strength against their weight

I could spend my birthday scanning the news

read how many missiles one country launched

and the other guys shot down

grind eighty-year-old teeth, those that remain

over loss and disappointment, how we fail

and fail and fail to distinguish truth from lies

instead, I will walk in the sun

rejoice in my loves and my adventures

marvel that I've survived until today

when little girls wear fairy wings and tutus

and princess crowns in the New York streets

and grow up to be neurosurgeons and CEOs

and astronauts as if they have forever

I'll wear a sparkling tiara to my birthday dinner

and dance down Columbus Avenue if I want to

as if they have forever

08 December 2025

The thing about fiction and poetry

Decades before I ever wrote a publishable novel or short story, I was writing poems that did the same thing in fewer words. What is “the thing,” you ask?

Some poems tell a story.

on the stage of Carnegie Hall

rich and dark and gleaming

they seem to surround me

each tier’s apex a velvet throat

hidden in the depths, the rows of jaws

yawn wide as if to snap

on this twelve-year old girl

from “Orchestra Class,” first published in Yellow Mama; in my new collection, The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle

Some poems make people think.

I am the daughter of the son of the daughter

of a woman whose name no one remembers

though all the oldest still alive and sane

were there last time I asked

from “I Am the Daughter,” the title poem in

my first collection, I Am the Daughter

Some poems make people laugh.

my mother rejects the unconscious...

her house is clean...

when she visits the optometrist

she peers fiercely at the eye chart

and tries to put her glasses on

she is 20-20 at life

but wants an A in both eyes too.

from “My Mother Rejects the Unconscious,” first published in Sojourner;

in my first collection, I Am the Daughter

Some poems make people cry.

when I sleep in my parents’ house

they make up the bed I traded in my crib for

the pine tree outside my window

still catches stars in its branches

the pine tree is still growing

it frightens me

having so much to lose

from “On Borrowed Time,” in I Am the Daughter

Some poems surprise people.

then there was the day I took them to the zoo

riding the subway up to the Bronx...

we looked as normal as anyone in the car...

three of the paranoid schizophrenics took a ride

on the aerial tram, but I was too scared

of heights to go along

they snapped my picture smiling

from “Outing,” first published in Home Planet News; in my second collection, Gifts and Secrets

Some poems hold up a mirror to our conscious or unconscious selves.

Whether I’m writing a poem, a short story, or a novel, the creative process is the same. Some call it it inspiration or being "in the zone." The process of writing a new short story may begin with what I call “my characters talking in my head.” A novel requires such a long period of sustained effort that it demands a high ratio of slogging to inspiration. But those moments are equally familiar to my inner poet. I wrote about one such moment long before I realized that other writers had the same experience.

it's like The Red Shoes only instead of dancing

I keep getting up to write poems

a dozen times between 3 and 6 AM

I curl back around you in the dark

and pull the blankets up

but then a line tugs at my mind

and I go stumbling through the hall

groping for light and pen

each time I lie back down

the images pop up like frogs

clamoring to be made princes

and you grumble and roll over

as I shuffle into my slippers once again

and go kiss the page

from “Night Poem,” in Gifts and Secrets

For me, the main difference between the two crafts is that, like other fiction writers, I say, “I tell lies for a living,” and I’m only half kidding—well, completely kidding about the “living” part. As a poet, I say, “All of my stories are true.” In my novels and short stories, my goal is to create fictional characters who leap off the page, made-up characters so real that the reader not only believes, but falls in love with them. In my poetry, the ring of authenticity comes from lived experience.

Some poems have something to say.

The poet’s craft is speaking my truth and turning it into art as opposed to hitting you over the head with it. My new book, The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle, took more than two years to write. When I started writing poetry again for the first time in twenty years, I was much too angry at the state of the world to create art rather than polemic. It took everything I’d learned about patience as a novelist and about revision as a short story writer to write good poems that said what I wanted to say. Over that period, as the world got even more chaotic and the future more uncertain, I learned that I also had something to say about hope, connection, love, and peace of mind.

but ah, the whale! there’s a creature of the now

no anxiety, no regret, a vast serenity

in the greater vastness of the sea

singing while we moan about how to fix it all

swimming parallel to our troubled world

from “Afternoon On the Beach,” first published in

Yellow Mama; in The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle

All poems © Elizabeth Zelvin

The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle is available as paperback or e-book.

Liz's other poetry collections, short fiction collections,

and novels are all available as e-books.

Poetry by Elizabeth Zelvin

Bruce Kohler Mysteries

Mendoza Family Saga

10 November 2025

The Old Lady Shows her Mettle

If you're Jewish, you'll get the reference.

"This book" is my new poetry book, The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle.

First, let me tell you my numbers. I'm 81 years old. I've been a writer since I was seven. My first book of poetry was published when I was 37. My first short story was published when I was 63. My first novel was published when I was 64. I've published three poetry books, seven novels, and more than 60 short stories. As a novelist, I've had and been dropped by three agents and five publishers. I've had novels in hardcover and poems in journals that folded before some of you were born.

So why is this book different?

1. The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle is the voice of a vanishing generation. My poems were published widely during the Second Wave of the women's movement. I was a New York Jewish feminist poet. My first book, I Am the Daughter, was about that political sensibility as well as being a young mother and my love life at the time. As I discovered when I looked for old poet friends to ask if they would consider blurbing the book, not many of us are left. In the late 1970s, a group of young mothers traded poetry critique on the Upper West Side. One of us went on to become revered, a household name, a Pulitzer winner. Her assistant wrote she sent best wishes but her health was too poor even to read emails. That's the way it goes when you're over 80.

2. I self-published The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle in print and e-book editions, after shopping it for a year. The poetry world is different from the mystery and crime fiction world I know, so I asked an old friend, a highly regarded award-winning poet, about reading fees. I was surprised when he didn't say he turned up his nose at them. "Not any more,"he said. So I did what I had to and got two offers. The catch was that the contracts were for print books. The publishers insisted on owning the electronic rights but did not intend to issue an e-book.

3. The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle is my only poetry book available in print as well as e-book form. Both I Am the Daughter (1981) and Gifts and Secrets (1999), my mid-life book, which was about my work as a therapist, being a mother, and the beginning of losses—the death of friends and eventually of my parents—were originally published before the digital world existed. But I re-issued them as e-books a few years ago, the rights having reverted, with a few editorial tweaks I'd been longing to make for forty years.

4. The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle is my "Jewish book" in a way that even the Mendoza Family Saga, my Jewish historical adventure series set in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, is not. For one thing, fiction, as we fiction writers like to say, is "telling lies." Poetry, at least for me, is always about the truth. "All my stories are true," I say at readings. Some of these poems tell stories about the emigration of my family from Hungary and what we then called the Ukraine to New York and what happened to those who stayed, those left behind, and any who got homesick and went back. Others, the most difficult to write, were my way of working through the divisive effect that political and environmental events from 2019 to the present have had on the world and various entities and institutions, including publishing, the American left, and the community of Jewish friends on whom I've depended all my life. All this and the rise of anti-Semitism in the US and throughout the world have made me aware of and willing to declare my identity as a Jewish woman in a way that I never have before, certainly not in my poetry.

5. The Old Lady Shows Her Mettle includes grandmother and granddaughter poems that are not about a grandma rocking or hugging the grandchildren or feeding them, cooking, or otherwise confined to the kitchen. While I was looking for places to submit my new poetry, I was horrified that I could find no current poetry by men and little by women portraying grandmothers outside traditional gender-based roles. As these poems attest, my granddaughters and I order in, go out, and talk about stuff that matters.

21 April 2024

The Tintinnitus of the Bells, Bells, Bells

by Leigh Lundin

My parents used to rebuke us: “Enunciate!”

Humph. I didn’t think I spoke badly, but they would’ve instructed the nation with resolutely precise enunciation if they’d had their own Discord and YouTube channels.

A couple of decades later found me in France at a colleague’s dinner table talking about the weather. I mention the harsh winter in Minnesota and my French friend stopped me.

“The harsh what?” he asked.

“Harsh winter,” I said. At his request, repeated it yet again.

He said, “I don’t understand.”

“Spring, summer, autumn, winter.”

He looked puzzled. “I thought winter had a T in it.”

He was right. I wasn’t pronouncing the T. Same with ‘plenty’. Likewise, I pronounced only the first T in ‘twenty’'. Some words with an ’nt’ combination – but not all– lost their ’T’s coming out of my mouth.

Banter and canter, linty and minty seem fine, but I swallow the T in ‘painter’. Returning after a year overseas and more conscious of enunciation, I sounded like a foreigner. “I just love German accents,” said my bank teller, cooing and fluttering her eyelashes.

Language in Flux

By age 8 or so, I’d become adept at soldering and still use the skill for repairs, projects, and mad scientist experiments. Pitifully, it took me decades to realize I didn’t know how to pronounce it.

I’m not sure if it’s a Midwestern thing or an American attribute, but I leave out the bloody letter L. Most people I know pronounce that compound of tin, lead, and silver as “sodder.”

I don’t do that with other LD combinations like bolder, colder, and folder. Even with practice, solder with an L does not trip readily off my tongue.

The Apple electronic dictionary that comes with Macs shows North American pronunciation as [ ˈsädər ]. Interesting… no L. Then I switched tabs to the British English dictionary where I learned it’s pronounced [ ˈsɒldə, ˈsəʊldə ]. Okay, there’s an L. But hello… What’s this? What happened to the R? Whoa-ho-ho.

Speaking of L&R, when was the R in ‘colonel’ granted leave? Kernel I understand; colonel, not so much. What about British ‘lieutenant’? The OED blames the French, claiming ‘lievtenant’ evolved to ‘lieutenant’ but pronounced ‘lieftenant’.

Finally, what happened to the L in could, would, and should? They seem to have broken the mould. The Oxford lords giveth and they taketh away.

Sounds of Silence

I know precisely why another word gave me difficulty. I tended to add a syllable to the word ‘tinnitus’, which came out ‘tintinnitus’. I’ve puzzled an otolaryngologist or two, because I conflated tinnitus with tintinnabulation.

(Otolaryngologist? Speak of words difficult to pronounce!)

Which brings us to a trivia question all our readers should know: How does ‘tintinnabulation’ connect with the world of mystery?†

Rhymes Not with Venatio

Before Trevor Noah became a US political humorist, his career began as a South African standup comic. On one of his DVDs, he altered words to sound snooty and high class, such as ‘patio’ rhymed with ‘ratio’.

Junior high, Bubbles Mclaughlin: nineteen months and three days older than me. Like Trevor, this ‘older woman’ had no idea how to pronounce another word ending in ‘atio’. For years, neither did I, but she could have rhymed it with ‘aardvark’ and I wouldn’t have minded.

C Creatures

I’ve been listening to ebooks recently. Almost all text-to-speech apps claim to use buzzwordy AI, but most don’t, not when ‘epitome’ sounds like ‘git home’. Similarly, ‘façade’ does not rhyme with ‘arcade’.

When making the Prohibition Peepers video, I altered spelling of a few words to get the sound I needed, such as ‘lyve’ instead of ‘live’. What a pane in the AIss.

I wondered if ebook programs would pronounce façade correctly if their closed captions were correctly spelled with C-cédille, that letter C with the comma-looking tail that indicates a soft C. If you stretch your imagination, you can kinda, sorta imagine a cedilla (or cédille) looking a little like a distorted S. (For Apple users employing text-to-speech, a Mac pronounces it correctly either way.)

Our local Publix grocery (when their founder’s granddaughter and heiress isn’t funding riots) spells the South American palm berry drink as ‘acai’, which meant both employees and I sounded it with a K. If they’d spelled ‘açai’ with the C-cédille, I would have learned the word much sooner.

I could say ‘anemone’ before I knew how to spell it. The names of this flower and sea creature are spoken like ‘uh-NEM-uh-nee’, which rhymes with ‘enemy’.

Bullchit

Permit me to introduce you to Rachel and Rachel’s English YouTube channel. She kindly explains we often learn words through reading and don’t learn their sound until much later. I was shocked that three of the words she led with have given me trouble including one I hadn’t realized I was currently mispronouncing– echelon. I was saying it as CH (as in China) instead of SH (as in Chicago).

Those other two words: In grade school, I became confused how to say mischievous and triathlon, requiring more careful attention.

Rachel also discusses how modern usage omits syllables. I say ‘modern’ because my teachers would have rounded smartly on us had we dared abbreviate, so I tend to fully sound out several of her examples. One she doesn’t mention is ‘secretary’, at times said as ’SEK-ruh-tree’.

When is a T not a T?

The phrase ‘can not’ has been shortened and shortened again over time:

- can not

- cannot

- can’t

- can’

What? Rachel enters extreme territory beyond my ken, explaining the ’stop-T’. Listen to what she has to say about it. That’s all for now!

† Answer to trivia question: Edgar Allan Poe famously used the obscure but wonderful word ‘tintinnabulation’ in his poem, ‘The Bells’.

31 March 2024

Nursery Crimes and Grim Fairie Tales

by Leigh Lundin

Last week, we brought you the surprise discovery of Zelphpubb Blish’s L’Histoire Romantique et les Aventures Malheureuses de Jacques Horner Hubbard Ripper Beanstalker Candlesticken Spratt,† also titled Grim Faerie Tayles, a crime story believed lost to the ages.

Thanks to an arrangement with the British Museum non-Egyptian archives at the University of Brisbane in Glasgow, we are pleased to bring you this legendary poem, a work considered to rival William McGonagall’s Scottish translation of Poetic Edda.

The Curiously Murderously Nursery Mysteriosity Atrocity

A Grim Faerie Tale by Zelphpubb Blish (1419-1456)

Happy Easter and April Fool’s Eve.

† Spratt was known to ingest no polyunsaturated fat substitutes rendering poisoning difficult.

‡ Last year, we shared a nursery rhyme about a greedy sister by Australian poet David Lewis Paget.

20 August 2023

English Chaos

by Leigh Lundin

|

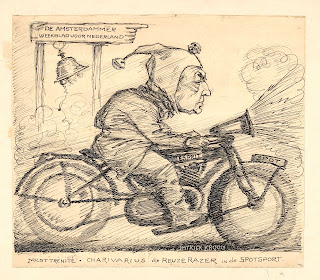

| Sketch of Gerard Nolst Trenité aka Charivarius |

In the spirit of the ‘English, English’ article two weeks ago and recent essays about the madness of the language, I dug out a copy of ‘The Chaos’. Its author, Gerard Nolst Trenité, who went by the nom de plume of Charivarius, was a Dutch writer, traveller, law and political science student, teacher, playwright, and noted contributor to the English language. More than a century ago, he gathered some 800 trickiest English irregularities into a 274 line poem called ‘The Chaos’ as a practice suite for his students.

Subsequent versions were adopted and maintained by the Simplified Spelling Society. Abrupt lapses in style and occasional losses of mètre suggest others may have tinkered with the piece, much like a recipient ‘improves’ an email tidbit before passing it along. Trenité himself dropped and added words in subsequent versions, and popular stanzas have been restored by historians. Any way it’s viewed, the collection impresses readers a hundred years later.

Note: This rendition carries over the formatting and indentation passed down by Trenité. Originally staggered couplets hinted at senses of masculine and feminine as used in other Romance languages, and they can still be comfortably read with alternating male and female voices.

Here now is…

| Dearest creature in Creation, |

| Studying English pronunciation, |

| I will teach you in my verse |

| Sounds like corpse, corps, horse, and worse. |

| I will keep you, Susy,† busy, |

| Make your head with heat grow dizzy; |

| Tear in eye, your dress you'll tear; |

| So shall I! Oh, hear my prayer. |

| Pray, console your loving poet, |

| Make my coat look new, dear, sew it! |

| Just compare heart, beard, and heard, |

| Dies and diet, lord and word. |

| Sword and sward, retain and Britain |

| (Mind the latter, how it's written!) |

| Made has not the sound of bade, |

| Say-said, pay-paid, laid, but plaid. |

| Now I surely will not plague you |

| With such words as vague and ague, |

| But be careful how you speak, |

| Say break, steak, but bleak and streak. |

| Previous, precious, fuchsia, via; |

| Pipe, snipe, recipe and choir, |

| Cloven, oven; how and low; |

| Script, receipt; shoe, poem, toe. |

| Hear me say, devoid of trickery: |

| Daughter, laughter and Terpsichore, |

| Typhoid; measles, topsails, aisles; |

| Exiles, similes, reviles; |

| Wholly, holly; signal, signing; |

| Thames; examining, combining; |

| Scholar, vicar, and cigar, |

| Solar, mica, war, and far. |

| From 'desire': desirable– admirable from 'admire'; |

| Lumber, plumber, bier, but brier; |

| Chatham, brougham; renown but known, |

| Knowledge; done, but gone and tone, |

| One, anemone; Balmoral; |

| Kitchen, lichen; laundry, laurel; |

| Gertrude, German; wind and mind; |

| Scene, Melpomene, mankind; |

| Tortoise, turquoise, chamois-leather, |

| Reading, Reading, heathen, heather. |

| This phonetic labyrinth |

| Gives moss, gross, brook, brooch, ninth, plinth. |

| Have you ever yet endeavoured |

| To pronounce revered and severed, |

| Demon, lemon, ghoul, foul, soul, |

| Peter, petrol and patrol? |

| Billet does not end like ballet; |

| Bouquet, wallet, mallet, chalet. |

| Blood and flood are not like food, |

| Nor is mould like should and would. |

| Banquet is not nearly parquet, |

| Which is said to rhyme with 'darkly'. |

| Viscous, viscount; load and broad; |

| Toward, to forward, to reward, |

| Ricocheted and crocheting, croquet? |

| And your pronunciation's okay. |

| Rounded, wounded; grieve and sieve; |

| Friend and fiend; alive and live. |

| Is your R correct in higher? |

| Keats asserts it rhymes Thalia. |

| Hugh, but hug, and hood, but hoot, |

| Buoyant, minute, but minute. |

| Say abscission with precision, |

| Now: position and transition. |

| Would it tally with my rhyme |

| If I mentioned paradigm? |

| Twopence, threepence, tease are easy, |

| But cease, crease, grease and greasy? |

| Cornice, nice, valise, revise, |

| Rabies, but lullabies. |

| Of such puzzling words as nauseous, |

| Rhyming well with cautious, tortious, |

| You'll envelop lists, I hope, |

| In a linen envelope. |

| Would you like some more? You'll have it! |

| Affidavit, David, davit. |

| To abjure, to perjure. Sheik |

| Does not sound like Czech but ache. |

| Liberty, library; heave and heaven; |

| Rachel, ache, moustache, eleven, |

| We say hallowed, but allowed; |

| People, leopard; towed, but vowed. |

| Mark the difference, moreover, |

| Between mover, plover, Dover, |

| Leeches, breeches; wise, precise; |

| Chalice but police and lice. |

| Camel, constable, unstable; |

| Principle, disciple; label; |

| Petal, penal, and canal; |

| Wait, surmise, plait, promise; pal. |

| Suit, suite, ruin; circuit, conduit |

| Rhyme with 'shirk it' and 'beyond it.' |

| But it is not hard to tell |

| Why it's pall, mall, but Pall Mall. |

| Muscle, muscular; gaol, iron; |

| Timber, climber; bullion, lion, |

| Worm and storm; chaise, chaos, chair; |

| Senator, spectator, mayor. |

| Ivy, privy, famous; clamour |

| And enamour rime with 'hammer.' |

| Pussy, hussy, and possess, |

| Desert, but desert, address. |

| Golf, wolf, countenance, lieutenants |

| Hoist in lieu of flags left pennants. |

| Courier, courtier, tomb, bomb, comb, |

| Cow, but Cowper, some, and home. |

| Solder, soldier! Blood is thicker, |

| Quoth he, 'than liqueur or liquor', |

| Making, it is sad but true, |

| In bravado, much ado. |

| Stranger does not rhyme with anger, |

| Neither does devour with clangour. |

| Pilot, pivot, gaunt, but aunt, |

| Font, front, wont, want, grand, and grant. |

| Arsenic, specific, scenic, |

| Relic, rhetoric, hygienic. |

| Gooseberry, goose, and close, but close, |

| Paradise, rise, rose, and dose. |

| Say inveigh, neigh, but inveigle, |

| Make the latter rhyme with eagle. |

| Mind! Meandering but mean, |

| Valentine and magazine. |

| And I bet you, dear, a penny, |

| You say mani-(fold) like many, |

| Which is wrong. Say rapier, pier, |

| Tier (one who ties), but tier. |

| Arch, archangel; pray, does erring |

| Rhyme with herring or with staring? |

| Prison, bison, treasure trove, |

| Treason, hover, cover, cove, |

| Perseverance, severance. Ribald |

| Rhymes (but piebald doesn't) with nibbled. |

| Phaeton, paean, gnat, ghat, gnaw, |

| Lien, psychic, shone, bone, pshaw. |

| Don't be down, my own, but rough it, |

| And distinguish buffet, buffet; |

| Brood, stood, roof, rook, school, wool, boon, |

| Worcester, Boleyn, to impugn. |

| Say in sounds correct and sterling |

| Hearse, hear, hearken, year and yearling. |

| Evil, devil, mezzotint, |

| Mind the Z! (A gentle hint.) |

| Now you need not pay attention |

| To such sounds as I don't mention, |

| Sounds like pores, pause, pours and paws, |

| Rhyming with the pronoun yours; |

| Nor are proper names included, |

| Though I often heard, as you did, |

| Funny rhymes to unicorn, |

| Yes, you know them, Vaughan and Strachan. |

| No, my maiden, coy and comely, |

| I don't want to speak of Cholmondeley. |

| No. Yet Froude compared with proud |

| Is no better than McLeod. |

| But mind trivial and vial, |

| Tripod, menial, denial, |

| Troll and trolley, realm and ream, |

| Schedule, mischief, schism, and scheme. |

| Argil, gill, Argyll, gill. Surely |

| May be made to rhyme with Raleigh, |

| But you're not supposed to say |

| Piquet rhymes with sobriquet. |

| Had this invalid invalid |

| Worthless documents? How pallid, |

| How uncouth he, couchant, looked, |

| When for Portsmouth I had booked! |

| Zeus, Thebes, Thales, Aphrodite, |

| Paramour, enamoured, flighty, |

| Episodes, antipodes, |

| Acquiesce, and obsequies. |

| Please don't monkey with the geyser, |

| Don't peel 'taters with my razor, |

| Rather say in accents pure: |

| Nature, stature and mature. |

| Pious, impious, limb, climb, glumly, |

| Worsted, worsted, crumbly, dumbly, |

| Conquer, conquest, vase, phase, fan, |

| Wan, sedan and artisan. |

| The TH will surely trouble you |

| More than R, CH or W. |

| Say then these phonetic gems: |

| Thomas, thyme, Theresa, Thames. |

| Thompson, Chatham, Waltham, Streatham, |

| There are more but I forget 'em— |

| Wait! I've got it: Anthony, |

| Lighten your anxiety. |

| The archaic word albeit |

| Does not rhyme with eight-you see it; |

| With and forthwith, one has voice, |

| One has not, you make your choice. |

| Shoes, goes, does. Now first say: finger; |

| Then say: singer, ginger, linger. |

| Real, zeal, mauve, gauze and gauge, |

| Marriage, foliage, mirage, age, |

| Hero, heron, query, very, |

| Parry, tarry fury, bury, |

| Dost, lost, post, and doth, cloth, loth, |

| Job, Job, blossom, bosom, oath. |

| Faugh, oppugnant, keen oppugners, |

| Bowing, bowing, banjo-tuners |

| Holm you know, but noes, canoes, |

| Puisne, truism, use, to use? |

| Though the difference seems little, |

| We say actual, but victual, |

| Seat, sweat, chaste, caste, Leigh, eight, height, |

| Put, nut, granite, and unite. |

| Reefer does not rhyme with deafer, |

| Feoffer does, and zephyr, heifer. |

| Dull, bull, Geoffrey, George, ate, late, |

| Hint, pint, senate, but sedate. |

| Gaelic, Arabic, pacific, |

| Science, conscience, scientific; |

| Tour, but our, dour, succour, four, |

| Gas, alas, and Arkansas. |

| Say manoeuvre, yacht and vomit, |

| Next omit, which differs from it |

| Bona fide, alibi, |

| Gyrate, dowry and awry. |

| Sea, idea, guinea, area, |

| Psalm, Maria, but malaria. |

| Youth, south, southern, cleanse and clean, |

| Doctrine, turpentine, marine. |

| Compare alien with Italian, |

| Dandelion with battalion, |

| Rally with ally; yea, ye, |

| Eye, I, ay, aye, whey, key, quay! |

| Say aver, but ever, fever, |

| Neither, leisure, skein, receiver. |

| Never guess– it is not safe, |

| We say calves, valves, half, but Ralf. |

| Starry, granary, canary, |

| Crevice, but device, and eyrie, |

| Face, but preface, then grimace, |

| Phlegm, phlegmatic, ass, glass, bass. |

| Bass, large, target, gin, give, verging, |

| Ought, oust, joust, and scour, but scourging; |

| Ear, but earn; and ere and tear |

| Do not rhyme with here but heir. |

| Mind the O of off and often |

| Which may be pronounced as orphan, |

| With the sound of saw and sauce; |

| Also soft, lost, cloth and cross. |

| Pudding, puddle, putting. Putting? |

| Yes: at golf it rhymes with shutting. |

| Respite, spite, consent, resent. |

| Liable, but Parliament. |

| Seven is right, but so is even, |

| Hyphen, roughen, nephew, Stephen, |

| Monkey, donkey, clerk and jerk, |

| Asp, grasp, wasp, demesne, cork, work. |

| A of valour, vapid vapour, |

| S of news (compare newspaper), |

| G of gibbet, gibbon, gist, |

| I of antichrist and grist, |

| Differ like diverse and divers, |

| Rivers, strivers, shivers, fivers. |

| Once, but nonce, toll, doll, but roll, |

| Polish, Polish, poll and poll. |

| Pronunciation– think of Psyche!– |

| Is a paling, stout and spiky. |

| Won't it make you lose your wits |

| Writing groats and saying 'grits'? |

| It's a dark abyss or tunnel |

| Strewn with stones like rowlock, gunwale, |

| Islington, and Isle of Wight, |

| Housewife, verdict and indict. |

| Don't you think so, reader, rather, |

| Saying lather, bather, father? |

| Finally, which rhymes with enough, |

| Though, through, bough, cough, hough, sough, tough? |

| Hiccough has the sound of 'cup'. |

| My advice is: give it up! |

† ‘Dearest Creature Susy’ is believed to reference French student Susanne Delacruix.