There are probably as many Rules for Writers as there are writers. Maybe more. The rule I’m thinking of today goes like this: Don’t show your research.

A good author of fiction will often do a lot of digging before they write. Does that type of pistol have a safety? What symptoms does that poison cause? How much wood would a woodchuck—Never mind.

These details can make a story more believable and more interesting. But it has to look natural. If the reader thinks they have stumbled into a college lecture they may fall asleep out of sheer habit.

I try to avoid this trap but I must admit that sometimes, darn it, I want you to notice my research. This is partly because I am a recovering librarian, but mainly because when I write a historical mystery it is important to be clear when I am not just making things up.

| |

| Bandon, OR |

I have a story coming out in the next issue of Black Cat Mystery Magazine called “The Night Beckham Burned Down.” It was inspired by the actual tragic events that occurred in Bandon, Oregon in 1936.

Editor Michael Bracken was kind enough to let me put an Author’s Note at the end pointing out that many of the bizarre anecdotes in my story really happened. (For example, some people survived the wildfire by submerging themselves in a cranberry bog.) I simply imposed the true events on a group of fictional characters and, naturally, added a murder.

So that’s one way of handling the see-my-research problem. I used a different trick in my story in the November/December issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. “Christmas Dinner” is part of my series set in Greenwich Village in 1958, and there is an important clue based on something that really happened back then.

I thought it was important to make that clear. Why? Well, imagine the master detective announcing: “I knew John Fictional was the murderer because his middle name is Tyrone. That fact was never mentioned in this novel, but I just happened to know it.” You wouldn’t cheer; you’d probably throw the book away. Vigorously.

So I wanted the reader to know that my clue was based on an obscure fact but a genuine one. My solution was to have my detective, the beat poet Delgardo, announce the clue and then say “This is true. Look it up.” He is supposedly talking to his friends, but in reality I am having him speaking to my audience, hopefully without breaking the fourth wall.

I doubt if any of the readers really will look that fact up but at least they know they could.

Let’s get slightly off topic. Until I started writing this piece I had thought Delgardo said “You could look it up,” so I want to look at that longer phrase.

I easily found a website that credits the phrase to Yogi Berra, the legendary New York Yankees catcher and manager. He was also known as an amazing phrase-maker so it is not surprising that the term gets attributed to him, considering its baseball connection (What baseball connection? We will get to that.).

Berra’s talent was coming up with phrases that seemed to be half-incoherent and half-Zen koan. My favorite: “If the people don’t want to come out to the ballpark, nobody’s going to stop them.” And: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.” Believe me, I could go on.

But “You can look it up” is hardly a phrase worthy of the master. So it is not surprising that I found another website indignantly insisting that the creator was actually Casey Stengel, a legendary pitcher and manager.

Sorry, folks. He didn’t say it either.

|

| Eddie Gaedel |

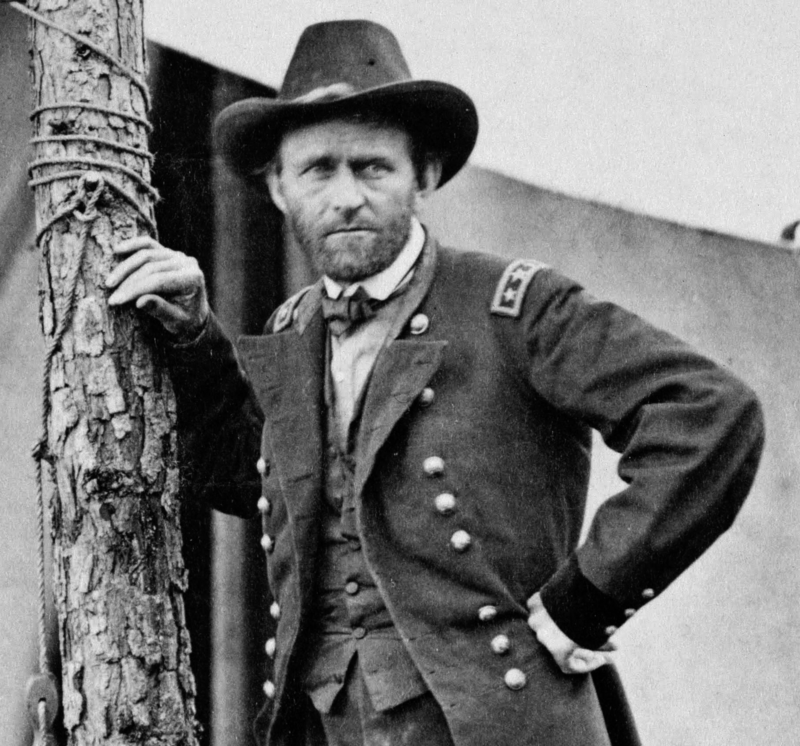

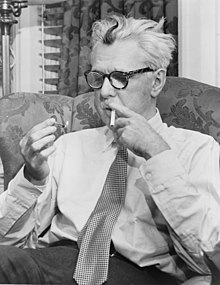

James Thurber (also legendary, but as an author not a ballplayer) wrote “You Could Look It Up,” a story which appeared in Saturday Evening Post in 1941. The narrator (who sounded a lot like Stengel, actually) told a wild tale about a baseball manager hiring a little person (Thurber said midget but that term is frowned on now) because “I wanted to sign up a guy they ain’t no pitcher in the league can strike him out.”

And here is where the fact and fiction coalesce again. In 1951 Bill Veeck, the owner of the famously awful and unlucky St. Louis Browns, hired Eddie Gaedel, a little person, as a pinch hitter for publicity's sake. He claimed he had forgotten about Thurber’s story until his man came up to bat.

Back to fiction. One more thing about my story “Christmas Dinner.” I suspect that if any readers complain it will not be about the aforementioned clue. If they do gripe will be about something else that occurs in the tale. “That’s not how X happens!” they will exclaim.

Ah, but I have a link to a website that proves that the way I describe X is exactly how it happened back in 1958.

And if they don’t believe me, they can look it up.