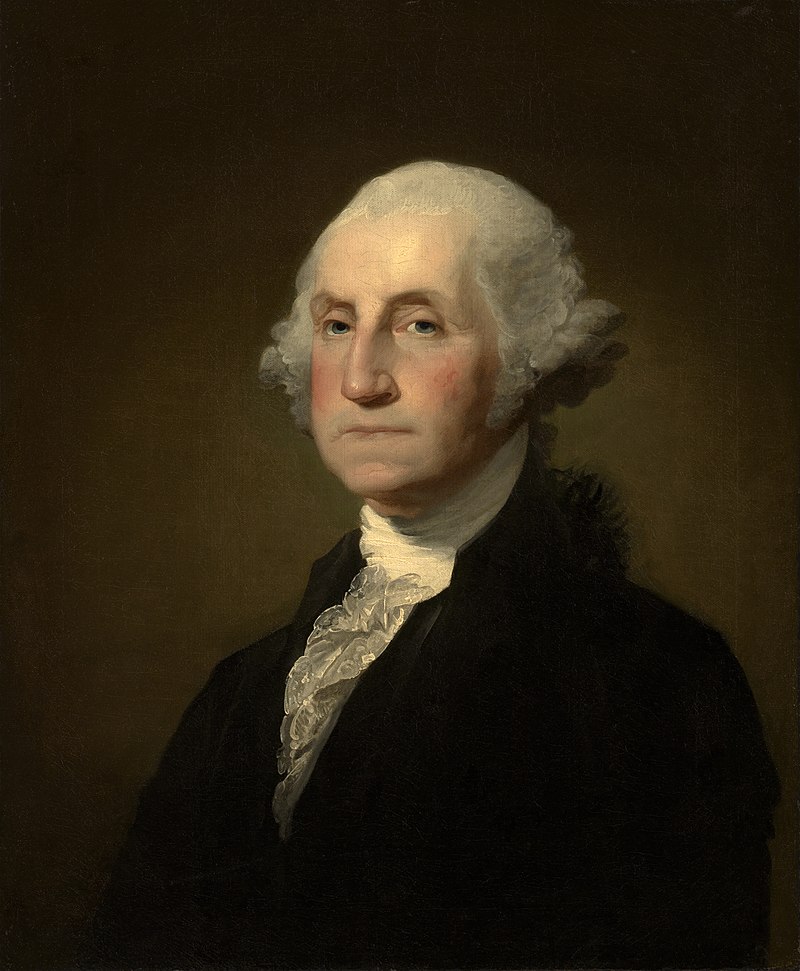

My father, the Big Band man, had a record in his collection that I heard quite a bit growing up. His 1971 album featured three pieces by the composer Aaron Copland, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra: Fanfare for the Common Man, Appalachian Spring, and Lincoln Portrait.

Lincoln Portrait is a fifteen-minute, music and spoken-word piece that is, as of this writing, eighty-four years old. Tradition calls for actors and other individuals of prominence to read the 400-word text. The recording I heard was performed by the actor Henry Fonda, who played the president in Young Mr. Lincoln and who subsequently ruined all other narrators for me. When I recently queued up Lincoln Portrait read by

Copland composed Portrait in 1942 when asked by the Russian-American composer Andre Kostelanetz to create a work that would celebrate a prominent American. World War II was on, and creative people of all types were being pressed into service to create art that would keep American minds on task. Copland suggested Whitman, but Jerome Kern had already picked Twain. Kostelanetz suggested Copland choose someone else—a statesman, not a writer. “[A]ny personality that is to be expressed with music should have some kind of humane aspect,” Copland would later tell an interviewer, “which is precisely what attracted me to Lincoln.”

As a subject, Lincoln was the perfect figure for that time, and always. Composers well before Copland had penned musical tributes to the gangly lawyer from Springfield. From the early part of the 20th century politicians of every stripe trotted him out, regardless of their persuasion. Progressives, leftists, radicals, Republicans and Democrats alike. FDR invoked him, suggesting that the Great Emancipator would have embraced the New Deal.

Copland had seen people suffer during the Depression; he was drawn to the plight of workers and the ideology of Communism, of all things, which would haunt his career after the war. But he, like others, believed Lincoln spoke for the common man (sans fanfare), the downtrodden, the masses. The words he selected from Lincoln’s writing hammered home principles that everyone who lived on the continent in that era had presumably agreed to embrace: freedom and democracy.

The historian Pauline Maier, in her book, American Scripture, discusses this at length. Lincoln’s genius was taking a forgotten document written in 1776 and linking it to a troubled moment in the mid 1800s, enshrining it as the nation’s critical founding document. The Constitution was the law of the land, but the Declaration was gospel. Lincoln had a flair for making political language sound sacrosanct.

In my thirties, I had a coach who loved smashing icons. He hated Democrats mostly, but for a born-and-bred Kentuckian he took strange aim at Lincoln. “You know,” he said once during a break in our sparring, “there is no evidence that he ever read a book.”

Bullshit, I thought then, and I stand by that today. Even before I knew about the sources he had drawn upon for his famous Cooper Union speech in 1860, it was obvious to me that Lincoln had read at least one tome: the King James Bible. Parallelism...chiasmus...he was all over it.

Copland incorporated five Lincoln texts in his Portrait. I’ve heard the piece so many times that I can practically quote them from memory. This week I went back and looked at the originals, in part to see what Copland left out.

In the selections that follow, I am bolding the lines Copland used. Copland did not preserve Lincoln’s underlines, which historians usually render as italics. The narrators of Lincoln Portrait are always given latitude to speak the lines as they see fit. The italics show which words Lincoln probably stressed.

Here’s the first, taken from the Annual Message to Congress, dated December 1, 1862, about a month before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation:

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We -- even we here -- hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free -- honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just -- a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.”You don’t have to go far, even in this selection, to see that its writer has wholly mastered that Biblical tone. When he uses an adverb, he makes it work. Words are not repeated unless they do double duty.

“We shall nobly save, or meanly lose…”

“In giving freedom…we assure freedom…”

He could have ended the graf with “and God must bless forever,” but then it would not so nicely echo “will forever applaud.” Ask yourself: is it a politician who has commanded our attention—or a preacher?

“fiery trial…”

“Plain, peaceful, generous, just…”

“Will light us down…”

Gotta admit, Coach: this is damn fine writing from a fellow who never cracked a book. We should all be so illiterate.

Copland’s second quote is taken from earlier in this very same message to Congress:

“The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise -- with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

I love this:

“quiet past…stormy present…”

“….is new, think anew, act anew.”

I have always liked the use of the word disenthrall in this sentence, but I needed to research what historians think he was really saying. They read it as tearing ourselves away from a system that we know is no longer working.

Copland’s third textual choice comes from the final debate with Stephen Douglas (October 15, 1858), in which Lincoln framed their senate race—as so many have—as a battle between good and evil, right and wrong. His oft-quoted “a house divided cannot stand” from this speech is paraphrased from the book of Matthew. But that’s not what Copland chose to quote. He went straight for the graf that would find favor with modern listeners:

“It is the eternal struggle between these two principles -- right and wrong -- throughout the world. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, 'You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.' No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.”

Earlier that year, Lincoln had made the same point, with similar phraseology, in another speech. Only then, instead of referring to this paradigm as "the same tyrannical principle," he dubbed it "the same old serpent."

A while back I learned that when Apple’s founder Steve Jobs was drafting a speech, for weeks he would tap out and shoot short emails to himself with a flurry of sentences and ideas that occurred to him. Lincoln did the same: he grabbed a sheet of paper and wrote short notes to himself. The three-line scrap that follows was found among his personal effects. He never inserted it into a speech, and his secretaries were unable to shed much light on their origin or intended use. Copland works it in as his third quote. And by now, coming after the tyrannical principle line above, two underlined words take on enlarged meanings. Again, these are Lincoln’s italics.

“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”Copland ends with the final 71 words of the Gettysburg address. I’ll spare you the lines. You can probably hear them in your soul.

Of the people, by the people, for the people.

He spoke those words on a battlefield after a far more famous orator intoned his way through a two-hour speech. Lincoln rose, spoke for two minutes, and later confided to friends that he had utterly botched it. “It is a flat failure,” he told his bodyguard.

Well, sure: what can we expect from such a bookless wonder?

During the Portrait’s premieres in 1942, Kostelanetz observed that the piece was received differently depending on the news of the day. When newspapers were filled with news of American victories abroad, thunderous applause. When the news was somber, audiences left hushed, perhaps struck by the long road ahead and the work democracy demands of us. And for a few years after World War II, Copland endured his own fiery trials at the hands of McCarthy.

And yes, I suppose I understand what Coach was getting at…maybe. Lincoln was no saint. Go back and read some of the fourth debate with Douglas. For the first half of the speech, he’s playing African Americans for laughs, bending over backward to reassure his audience that he doesn’t really think a black person will ever be the equal of a white person. Once he gets them on his side, he hammers home that if he had his druthers, he would change this one little thing about American life. But it’s an ugly windup.

But then, at Gettysburg, he again rescued that one word, equal, from a document many of his colleagues had either forgotten, maligned, or had willfully misremembered, insisting that we regard this dirty, five-letter word as the prime directive of the American experiment. One can see why historians find it hard to disenthrall themselves from his words and actions, even today. They probably never will.

A while back, when she spoke at the Abraham Lincoln Association in Springfield, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin told her audience:

“It’s not just that he was a great president, that he won the war, ended slavery, and saved the Union. It was his kindness, his sensitivity, his empathy, his willingness to let those past resentments go. I had the feeling that he had the normal human emotions of envy and anger and jealousy, but somehow he would say, ‘You have to damp them down because they’ll fester if you allow them inside. They’ll poison you.’”

She spoke those words in 2018. She was describing an imperfect human being who was, if nothing else, a well-read, mature adult. Even in 2018, the thought of a president who actively worked to shun resentment must have seemed quaint to her audience of Lincoln admirers in Springfield.