|

| Richard Helms |

Allow me to introduce my friend and wonderful writer, Richard ‘Rick’ Helms, author of a zillion award-winning novels and short stories, a man who’s received more nominations than an Iowa caucus. A former forensic psychologist, he oozes Southern charm and he’s witty and modest as well.

He and his wife Elaine live in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he still muscles out superb stories. You can find more about him on his web site. Now read on…

— Jan Grape

Bloom Where You’re Planted

by

Richard Helms

“We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.”

— Ernest Hemingway

I wrote my first full-length novel forty years ago. It wasn't published for another eighteen years, after going through dozens of submissions and two different agents. The Valentine Profile is still out there, and—being my first work—it's perfectly horribly awful, and I hang my head in shame every time I think about it. Please don't buy it. Or buy a caseload. You do you.

Despite years of disappointment and an almost legendary number of rejections, I persisted, and wrote four or five more novels, which also weren't published for many years. With each new title, I tried to stretch and improve, and each new book was incrementally better than the last.

I was always reminded of Raymond Chandler’s advice to analyze and imitate. Not surprisingly, most of my first half dozen or so novels are extremely derivative of the authors I was reading at the time—Robert Ludlum, David Morrell, David Hagberg, James Lee Burke, Robert B. Parker, and the like. It takes time to find your voice as an author, so for a while you borrow other people’s voices. There are those who still say—and they aren’t far wrong—that my Eamon Gold private eye series is still just Spenser transported to the west coast.

For years, I didn't even consider writing short stories. I didn't think I had the chops. Like many new writers, I presumed that real authors wrote novels—huge sweeping panoramas of human greed, suffering, conflict, passion, and inevitable death. I earned a Russian Studies minor in college—long story—and might have been influenced a bit by Tolstoy. Somewhere in the recesses of my autistic head, short stories were for quitters who put down Anna Karenina on only page 534.

More than that, though, I was convinced I couldn't say everything I wanted to in only a few thousand words. I thought that was a special skill, like shorthand, and I was playing hooky the day they handed it out.

This is really strange, because my most treasured physical possession is a book of—you guessed it—short stories.

It was my first ‘grown-up’ book. We were moving from Charlotte to Atlanta a week or so after I finished first grade, and our neighbors’ oldest son, who might have been twelve at the time, crossed the street as we were packing our car for the move to Georgia. He handed me a paperback book. He probably said something like, “My mom and dad said you like to read and stuff, and I had this lying around, so you can have it, okay?”

I prefer to remember the moment in the same emotional vein as the Lady in the Lake hefting aloft the mighty Excalibur, presenting it to Arthur. It was a turning point in my young life.

The book was Groff Conklin’s Big Book of Science Fiction. It was an anthology cobbled together from classic pulp science fiction magazines of the 1940s. There were stories by Lester Del Rey, Ray Bradbury, John D. McDonald, Murray Leinster, Fredric Brown, Clifford D. Simak, Theodore Sturgeon, and many more. As we tooled down the blue highways between Charlotte and Atlanta, I huddled in the backseat floor—as kids did sixty years ago—and read about robots and rockets and tiny unconscious homunculi used as currency and a funny alien named Mewhu and a man and a dog transformed into Jupiterian beings and time travel and all sorts of amazing concepts I’d never thought of before.

A lot of it didn’t make sense to me and was confusing, but most of it was amazing and astounding and made my little seven-year-old heart flutter. Groff Conklin’s Big Book of Science Fiction was my gateway drug to adult literature and pulp fiction at the same time. Dick and Jane? I didn’t care if they ran. I wanted to know why they ran. Why were they being chased? What horrible thing did they do? Dick and Jane might have been okay for the other second graders. I yearned for more. Groff Conklin’s Big Book of Science Fiction fed that hunger, and for the first time in my life, I understood that stories didn’t just happen, as Richard Brautigan wrote, like lint. Somebody had to write them.

Groff Conklin’s Big Book of Science Fiction is still my most prized physical possession. It resides in a special place on my bookshelf at home. If the house ever catches fire, I will see that Elaine and the cat are out, and then I’ll rescue the book. Everything else can be replaced. This book can’t, for one reason.

|

Theodore Sturgeon autograph

|

In 1978, I had dinner at UNC-Greensboro with Theodore Sturgeon and his partner, Lady Jayne. He was a guest of honor at a sci-fi convention at the college. He had written the story “Mewhu’s Jet” in my Sacred Book. I brought the by-then tattered paperback with me, and at a probably clumsy moment I thrust it into his hands and told him the story of how this book changed my reading life—and eventually inspired me to become a writer as well. He took one look at it, and said, “This book has been well-loved”, and he signed the first page of his story.

Sturgeon is long gone now, dead for over forty years. His autograph in my book with the added ‘Q’ with an arrow he used to symbolize “Ask the Next Question” can never be replaced. So the book gets rescued.

As illuminating as it was, Groff Conklin’s Big Book of Science Fiction was also intimidating. To me, the authors in those pages were giants, superhumans endowed with powers far beyond the grasp of mortal scribblers. They captured entire universes in five or six thousand words, and I was not worthy to look upon their visages.

So, I wrote novel after novel after novel. Twenty-five now and counting. Some were squibs. Some were award finalists. Not one of them has ever sold more than 1500 copies. That’s probably my fault, as I am much more comfortable tapping on a keyboard than pressing flesh. A born salesman, I am decidedly not.

In 2006, I decided to start a webzine publishing hardboiled and noir short stories, and solicited submissions on all the usual email listservs, the Facebook and Twitter of the day. Within weeks, I was swamped with submissions, a great number of which had been penned by Edgar and Shamus and Anthony Award winners. I was shocked.

Reading all those stories by such distinguished writers gave me an opportunity again to analyze and imitate. I pulled out my old trusty copy of Groff Conklin’s Big Book of Science Fiction, and I read those stories again as well. As I read, I discovered that the stories that had cowed me so completely decades earlier now made sense. I could recognize the use of a three-act structure and the economy of language in them. I had a little peek underneath the magicians’ capes. I thought, perhaps, I might be able to write in this strange, truncated style after all.

In 2006, I was mowing the grass and came up with an idea for my third Eamon Gold novel. Started working on it, and realized there wasn't enough there for a book, but it might make a nice short story. Longtime buddy Kevin Burton Smith published it on his Thrilling Detective Website, ("The Gospel According to Gordon Black") and it went on to win the Derringer Award that year. I had also written a short story for my own webzine, The Back Alley, entitled "Paper Walls/Glass Houses", and darned if it didn't win the Derringer as well.

No shit, dear readers. My first two published short stories were award winners, and made me one of only two authors ever to win the Derringer in two different categories in the same year. (The other is the incredibly prolific and masterful John Floyd.) Nobody was more surprised than I.

So I wrote another one, based on a failed Pat Gallegher novel, and retitled it "The Gods For Vengeance Cry." On a flyer, I sent it in to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and by golly Janet Hutchings bought it! It went on to garner nominations for the Derringer, Macavity, and Thriller Awards, and won the 2011 Thriller Award.

Yeah. My first THREE published short stories won awards. The fourth, "Silicon Kings" was also a Derringer finalist.

Clearly, it was time to reevaluate my writing priorities.

For almost a quarter century, before Kevin kindly published "The Gospel According to Gordon Black", I had always presumed that I was first and foremost a novelist, however obscure and failed. I had been conditioned to believe the fallacy that novels hold an exalted spot in literature. While I had enjoyed some limited critical acclaim with my novels, the sudden shocking success of the short stories left me wondering whether I had wasted thirty years of my writing life.

It’s a good thing I’m not into regrets.

Over the last fifteen years, I've embraced the idea that I might actually be a short story writer who dabbles in writing novels. I have six Shamus Award nominations (and one win) for my novels, but my short stories have garnered a mind-boggling fourteen nominations, and have won the Thriller, Shamus, and Derringer Awards. One story I wrote for anthology editor and master story craftsman Michael Bracken (“See Humble and Die”, in The Eyes of Texas, for Down and Out Books) was selected for the 2020 edition of Houghton-Mifflin-Harcourt’s Best American Mystery Stories, edited by Otto Penzler and C. J. Box.

And the hits just keep coming. Several years ago, the Republican National Convention was held in my hometown of Charlotte, NC. As happens in many cities, Charlotte made a concerted effort to get rid of the many homeless people who cluster each night along uptown Tryon Street, because images of people sleeping on bus stop benches make for bad national TV. I read an article about it in the news, and my first thought was that sweeping the streets of homeless people might make an excellent cover for a murder. Kill a homeless guy, hide the body, and everyone would think he was just given ‘Greyhound Therapy’—a bus ticket and twenty bucks to go somewhere (anywhere) else. I let the idea cook in my head for a week or two, mostly coming up with a compelling protagonist, and then I started typing. I threw in some stories I’d heard about living on the streets from my hippie buddies back in the early 1970s. The resulting story, "Sweeps Week" (EQMM, July August 2021) won the Shamus this year, and is a finalist for the Macavity at Bouchercon next week.

My wife said, “You know, you might have a knack for this.”

Sometimes I have to shake my head when I realize that one story in EQMM is seen (and hopefully read) by more people than have read all my novels put together. That's humbling, but also exciting. Unlike each new book, which might flop or fly, or even go completely ignored, the stories are being read. Nothing is more important to a writer.

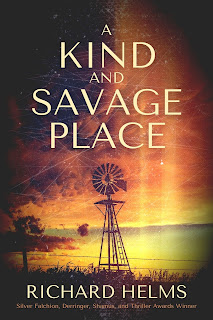

I still write novels. Earlier this year, Level Best Books’ New Arc imprint published A Kind and Savage Place, which traces the evolution of civil rights in the south as experienced by the citizens of a small North Carolina farming community. Next year, their Historia imprint will publish Vicar Brekonridge, a novel based on my Derringer Award-nominated EQMM short story “The Cripplegate Apprehension.” I recently finished a massive novel called 22 Rue Montparnasse, about the Lost Generation in post-WWI Paris, and I’m about ready to set sail on another novel about Laurel Canyon in the 1960s, inspired by the music of the late Nashville songwriter Larry Jon Wilson. None of these, with the possible exception of Vicar Brekonridge, is a traditional mystery story. Writing mystery short stories has freed me to explore other genres in my novel-length works, and to write the more mainstream and historical stories that I’ve back-burnered for years.

For now, though, my plan is to spend 2023 focused mostly on short stories. I’ve discovered that they are intensely rewarding. In what other medium can you come up with an idea on Tuesday, write “The End” on Friday, and people will buy it (hopefully)? In the same way I truly enjoy diving into massive amounts of research for a sweeping historical novel, I love the spontaneous nature of short stories. They’re almost like zen paintings, executed in seconds only after days of contemplation. The typing is only the last stage of storytelling. First, the story has to live inside your head. As Edward Albee once taught me in a master class, “Never put a sentence on the page until it can write itself.”

Living on the autistic spectrum, it would have been easy to stay rigidly glued to the novel-writing path. Comforting, even. Stability, structure, and adherence to a long-standing pattern of behavior is kind of a big deal among my neurodivergent tribe. Gritting my teeth, shutting my eyes, holding my breath, and breaking out and trying something new fifteen years ago turned out to make a huge difference in my writing life, and opened the door to a level of authorly satisfaction I had never known before.

My point is this (and it doesn't apply only to writing): The secret of happiness, I think, is to find your sunny spot and bloom where you're planted. If you beat your head against a door for years without an answer, maybe you're at the wrong door. I spent twenty-five relatively unhappy years working as a clinical/forensic psychologist, but only found career joy when I followed my true calling and became a teacher. Likewise, when I embraced short stories, the flower of my writing career blossomed.

Sometimes, it's a good idea to step back, survey the Big Picture, and figure out exactly where you fit into it, as opposed to where you want to fit. Life has a way of showing you the paths you need to tread, if you’re open to looking for them. A simple jink to the left or right could change your entire life. But, wherever you land, it should be the place that makes you happiest. Living as a tortured literary artist slaving in a dusty garret may be a romantic notion, but it isn’t much fun.

Sometimes, you win by trading one dream for another.