by John M. Floyd

I'm not much of a goal-setter, in my writing. Like all of us, I try to do a good job of writing stories and submitting them to markets--but beyond that, I don't feel there's much I can do. If something gets published, great. If something good happens

after it's published (awards, other recognition, etc.), that's icing on the cake, and I'm honored and grateful if/when it does. But that's out of my control.

Having said that, I think there are certain things that most mystery writers have on their bucket lists. One might be to win an Edgar, or even to be nominated. Or to win other writing awards, or to have a story picked up for a film. If you're a writer of short mysteries, an additional dream might be to appear in the annual MWA anthology or an Akashic noir anthology.

I've been fortunate enough to grab a few of these golden rings, as have most of you. One of my fantasies was realized last year, when I had a story chosen for

The Best American Mystery Stories 2015.

The B.A.M.S. file

I would guess that almost all of us have looked through volumes of

Best American Mystery Stories at one time or another. For those who might be interested, here's a quick overview of the series, and the procedure by which the included authors are selected.

The

B. A. M. S. anthologies began in 1997 and have always been published by Houghton Mifflin (later Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). In his introduction to the debut edition, series editor Otto Penzler explained that he identified and read all the mysteries published during the previous calendar year--1996--and chose the best fifty, which he then turned over to a guest editor. That editor, Robert B. Parker in this case, selected what he thought were the best twenty stories for the publication; the remaining thirty were listed in a close-but-no-cigar honor roll in the back of the book, called "Other Distinguished Mystery Stories of 1996." This process has been continued every year since. Those lucky enough to be in the "top 20" are notified, early in the year, that their stories will be featured in the book. Contracts are then sent out, the writers are paid, and the anthology is published in the fall.

Where does Otto go to find all this original fiction? "The most fruitful sources," he said in the

B.A.M.S. 1997 intro, "are the mystery specialty magazines, small literary journals, popular consumer publications, and an unusually bountiful crop from anthologies containing all or some original work." Apparently the field consisted of around 500 stories at first, and has now expanded to become 3,000 to 5,000 stories a year. His colleague Michele Slung apparently does most of the initial culling, and is, according to Otto, "the fastest and smartest reader I have ever known."

The names of all the guest editors can be found in the opening pages of every edition, but they're so impressive I'll list them here as well:

1997 - Robert B. Parker

1998 - Sue Grafton

1999 - Ed McBain

2000 - Donald Westlake

2001 - Lawrence Block

2002 - James Ellroy

2003 - Michael Connelly

2004 - Nelson DeMille

2005 - Joyce Carol Oates

2006 - Scott Turow

2007 - Carl Hiaasen

2008 - George Pelecanos

2009 - Jeffery Deaver

2010 - Lee Child

2011 - Harlan Coben

2012 - Robert Crais

2013 - Lisa Scottoline

2014 - Laura Lippman

2015 - James Patterson

2016 - Elizabeth George

20/50 vision

As I mentioned earlier, the stories featured in the anthology are the top twenty of the year, chosen by the guest editor. Those named in the Distinguished Mysteries list in the back of the book are the runners-up, the "rest" of the top fifty that were originally chosen by Otto Penzler.

I restated that because most folks don't know about it--including, until recently, me. At the 2012 Bouchercon I had the opportunity to meet Lee Child, one of my favorite authors. I remember saying to him (babbling, probably), "I saw that one of my stories was listed as "distinguished" in

The Best American Mystery Stories 2010 . . . and, well, since you were guest editor that year, I'd like to thank you for that honor." He said something kind and gracious and we both went on our way. What I didn't realize at the time was that my story was in the "distinguished" list because it was one of the fifty that Otto had selected, not one of the final twenty that Child chose. What I'd done, essentially, was thank him for

not picking my story to be in the book. Good grief.

An SS/B.A.M.S. history

From looking at my own editions of the series, snooping on the Internet, and pestering my fellow mystery writers for information I couldn't find elsewhere, I have created the following unscientific report of current and former

SleuthSayers who have wound up either in

Best American Mystery Stories or named in its "Other Distinguished Mystery Stories" list. Please forgive me, and correct me, if I've overlooked anyone.

year included in book (top 20) named in "distinguished" list (the rest of the top 50)

1997 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1998 ----Janice Law--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1999 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2000 ----David Edgerley Gates-------------------John Floyd----------------------------------------------------

2001 ----------------------------------------------------David Edgerley Gates-------------------------------------

2002 ----David Edgerley Gates-------------------R.T. Lawton---------------------------------------------------

2003 ----O'Neil De Noux--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2004 ----------------------------------------------------O'Neil De Noux, David Edgerley Gates----------------

2005 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2006 ----------------------------------------------------O'Neil De Noux-----------------------------------------

2007 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2008 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2009 -----------------------------------------------------Dixon Hill-------------------------------------------------

2010 -----------------------------------------------------Art Taylor, John Floyd-----------------------------------

2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2012 -----------------------------------------------------Eve Fisher, Janice Law, John Floyd--------------------

2013 -----O'Neil De Noux, David E. Gates-----Janice Law, B.K. Stevens-----------------------------------

2014 -----------------------------------------------------David Dean, Elizabeth Zelvin--------------------------

2015 -----John Floyd---------------------------------David E. Gates, Rob Lopresti, Art Taylor--------------

2016 -----Rob Lopresti, Art Taylor-----------------David E. Gates, R.T. Lawton, John Floyd--------------

Observations

Here are some things I found interesting about the above chart:

- As you can see, not one but TWO

SleuthSayers have stories that made it to the top 20 and into the book this year: Rob Lopresti and Art Taylor. Both are tremendously deserving of the honor, and--not surprisingly--neither of them is a stranger to the limelight. Both have been recognized with multiple awards and honors over the past several years.

(Art Taylor and I seem to have a strange connection: This year, when he made it into the book, I made the "Other Distinguished Mystery Stories" list; the year I managed to get in, he was in the "distinguished" list; and one year both he and I had stories listed as "distinguished." In other words, I always root for Art all the more, because if he's involved I seem to have a better chance of sneaking somewhere into the picture as well.)

- For the first 18 years of the series (before the 2015 edition of

B.A.M.S.), only three

SleuthSayers had stories featured in the book (top 20): David Edgerley Gates three times (2000, 2002, and 2013), O'Neil De Noux twice (2003 and 2013), and Janice Law once (1998). And only recently have

two SleuthSayers been in the top 20 in the

same year--O'Neil and David in 2013 and Rob and Art in 2016.

- When you combine the

SSers included in the book and those named in the "distinguished" list, David Edgerley Gates has made the top 50 an astounding

seven times (2000, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2013, 2015, 2016), I've made it five times (2000, 2010, 2012, 2015, 2016), O'Neil four (2003, 2004, 2006, 2013), Janice three (1998, 2012, 2013), Art three (2000, 2015, 2016), R.T. twice (2002, 2016), Rob twice (2015, 2016), and Dixon Hill, Eve Fisher, Bonnie Stevens, David Dean, and Liz Zelvin once each.

- David Edgerley Gates's stories were either included or named in the "distinguished" list in four out of five consecutive editions (2000-2004) and in another three out of four (2013-2016). Also, O'Neil De Noux's stories were either included or distinguished in three out of four consecutive years (2003-2006). A lot of fine stories over short stretches of time.

- In only six years out of

B.A.M.S.'s 20-year history have no

SleuthSayers been included in either the anthology or the "Other Distinguished Mystery Stories" list--but in one of those no-

SS years (1997)

Criminal Briefer Melodie Johnson Howe was featured in the book, and in another year (2011)

CBer Angela Zeman appeared in the "distinguished" list. And by the way, Angela was also included in the book in 2004 and

Criminal Brief founder James Lincoln Warren made the "distinguished" list in 2010. (I couldn't resist mentioning those colleagues;

Criminal Brief was the forerunner to

SleuthSayers, and Rob, Leigh, Janice, and I were all

CBers in a previous life.)

- In the before-I-forget department: Frequent

SS guest-blogger Michael Bracken was named to the "Other Distinguished Mystery Stories" list in 2005.

That's my take on

Best American Mystery Stories and its connection with our blog. If nothing else, it might steer you to some

SleuthSayers' stories in the old volumes you might already have on your bookshelves. (In the course of putting this column together, I wound up going back and reading a

lot of them.) May ALL of us be represented often in

B.A.M.S.'s pages in the future.

Many thanks to Otto Penzler, to his assistant(s) and his guest editors, and to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, not only for providing us with outstanding reading material but for giving some of us the opportunity, and the great honor, to be a part of the series.

Here's to another twenty years!

No, not that one, this one:

No, not that one, this one:

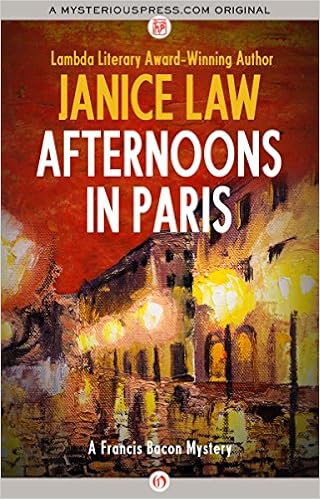

Yes, my favorite gay artist adventurer is back in Janice Law's "Afternoons in Paris". Francis is 18 and in the City of Lights, and very glad to be there after the craziness of Berlin (read Janice's "Nights in Berlin": the book and David Edgerley Gates' review). Now he's on his own, working for a decorator/designer by day (the somewhat susceptible Armand), visiting galleries with the motherly Madame Dumoulin, and cruising the city by night with the totally unreliable Pyotr, a Russian emigre who, like Francis, has a taste for quick hook-ups and rough trade.

Yes, my favorite gay artist adventurer is back in Janice Law's "Afternoons in Paris". Francis is 18 and in the City of Lights, and very glad to be there after the craziness of Berlin (read Janice's "Nights in Berlin": the book and David Edgerley Gates' review). Now he's on his own, working for a decorator/designer by day (the somewhat susceptible Armand), visiting galleries with the motherly Madame Dumoulin, and cruising the city by night with the totally unreliable Pyotr, a Russian emigre who, like Francis, has a taste for quick hook-ups and rough trade.