Pamela Beason wrote a piece for us not long ago and I wasn't expecting to have her back so quickly but when I read her novel THE ONLY WITNESS I loved it so much I invited her to write about it ASAP. And here she is. I think you will see why this unique idea appealed to me so much. - Robert Lopresti

When the Gorilla Takes Over

by Pamela Beason

When I began to write my novel The Only

Witness, I didn’t plan for it to be a series. Nor did I plan for Neema

the gorilla to be the protagonist of the book.

I was working as a

private investigator at the time, and I’d worked on several cases where

small children testified as witnesses. Now anyone who has worked with

young children, especially in a legal context, knows that they often

have limited understanding of the reality of what is happening to them

or around them, and we also know how easily they can be persuaded to say

the things that the adults want them to say. So, I had done a lot of

thinking about who can be a credible witness.

In addition to my

interest in investigation and legal issues, I’ve had a lifelong

fascination with animals of all kinds, and I’ve been especially curious

about animal intelligence. I always wondered why humans think we’re so

superior just because we can talk and write. All animals have their own

languages and talents. As a scuba diver, I’m amazed to see so many sea

creatures that can synthesize their own homes (shells) out of the sea

water that surrounds them, and I’m positively astounded to see an

octopus or a chameleon change the colors and patterns of their skins. My

cats can easily jump to the top of a wall that is seven times their

height. Tiny hummingbirds can hover in mid-air and survive the winters

along our coastlines. Animals make me feel inferior a lot of the time.

But

I digress… Getting back to the point, I’ve read all the books and

articles about teaching apes American sign language so we humans can

communicate in the only language we understand: The Education of Koko

and the films and National Geographic articles about the famous

gorillas, Roger Fouts’ Next of Kin, and some others.

So naturally my investigator brain got together with my animal-loving

side and cooked up the idea of having a gorilla, who supposedly has the

IQ of a five-year-old, be the only witness to a baby’s kidnapping. Cool

idea, right? But I resolved to keep the whole story plausible, so I had

to work with an ape’s limitations. A gorilla is never going to say, “You

know, when we were in town at 3 p.m. yesterday, I saw the most curious

incident when a shaggy-haired man…” So Neema’s clues had to be more

along the line of “Snake arm make baby cry. Give banana now.”

I

thought readers would sympathize more with beleaguered Detective Matthew

Finn, who initially cannot find any witness to what actually happened

when an infant vanishes from a car, and then, when he finally deduces

that he does have a witness, she’s a gorilla. How can he find out what

she actually knows? And what does he do with the clues when he finally

figures them out? No court is going to accept the “testimony” of an ape

who constantly bargains to trade questionable descriptions like “skin

bracelet” for yogurt and lollipops (aka “tree candy” in Neema-speak).

Readers

fell in love with Neema the gorilla and wanted more of her. I’m not

sure anyone even remembered my poor detective’s name, nor that of the

scientist (Grace McKenna) who teaches Neema, or even of the teen mom

(Brittany Morgan) whose infant was kidnapped. So then pressure from

readers forced me to write a sequel with gorillas—The Only Clue, in

which Neema, her mate Gumu, and her baby Kanoni all disappear after a

public event. And then, because any author knows that two books do not a

“series” make, I had to rack my brains to come up with a third. But

just how long can an author invent realistic mysteries involving signing

apes? It’s a challenge, let me tell you.

The Only One Left has sort of a

nebulous connection to a crime, because the gorillas discover evidence

in their barn that Detective Finn eventually deduces may have something

to do with a current case he’s assigned to. But readers don’t seem to

care too much about the premise. The gorillas are back! I like to think

that Koko, the real signing gorilla who passed away not so long ago,

lives on through my books.

Gorilla mysteries are also a marketing

challenge. When asked for other mysteries that are similar to my Neema

series, my response is generally, “Uh…” Likewise, when asked what the

next Neema mystery will be about, I’m clueless as to whether there could

even be another.

So, if anyone has any ideas on either of those

subjects, please send them to me right away. In the meantime, I’ll be

working on the next novel in my Sam Westin wilderness series. It’s so

much easier to solve crimes on public lands than to determine what the

heck three gorillas might be up to these days.

28 June 2019

When the Gorilla Takes Over

27 June 2019

A Letter From Middle School

by Brian Thornton

As I've written before, my day gig is teaching middle school history. As a middle school teacher (or as a public school teacher at any level, for that matter), I can attest to the importance of the month of June as both a signpost and a destination: a door into another year, another phase of life.

This is especially true for kids moving from middle to high school.

This year the mother of one of my students informed me that every year since her son was in kindergarten she had asked his teacher to write a letter to him at the end of the year. This year he had SIX different teachers (remember, it's middle school): and she chose to ask me because he had told her many times that I was his favorite teacher.

Phew.

Of course I said yes. No small obligation, because (as any teacher can tell you, the end of the school year is BUSY!

I've posted what I came up with below. Not least because we live in a cynical age, and I find the people I work with, the current generation currently coming into their late teens so heartening to be around. I honestly believe these kids are going to save the planet.

Dear XXXX-

I was honored when your mom told me about your family’s tradition of having a teacher write you a letter for every year of school in your life, and asked that I write this year's letter. Not surprising, I guess, that a history teacher would have an appreciation for tradition, right?

One of the reasons I so enjoy teaching 8th grade is that I get to meet young people on the cusp of adulthood–literally in the act of becoming who they are going to be for the rest of their lives. And I am so happy to have met YOU this year. You, Mr. XXXX, are a fine young man. And it has been my pleasure and my honor to serve as your teacher.

You have so much great stuff ahead of you–not just high school, but your entire life–just remember that this journey you’re on is a marathon (the race, not the Greco-Roman battle! HA! Ancient History joke!), not a sprint, and it’s very important that you take a moment every now and again to look around and take it all in. The memories you make this summer, and in high school, will stay with you, and inform and influence the choices you make and the paths you take in the years to come.

With that in mind, try to surround yourself with good people. We meet all kinds of folks in life- those who fill you up? Try to keep them around. Those who wear you out? Let them go. You’re possessed of a giving nature and a good heart, XXXX- and you deserve to get that back from the people in your life.

Most of all, please remember to be as good to yourself as you are to others. And like I said before, take the time to enjoy this life while you’re living it!

Nearly lastly, please thank your parents for me. First, for sending you to us here at XXXXXXXX, and second for asking that I write you this letter.

And lastly, THANK YOU for everything you’ve done this year. I always end the school year feeling as if my students have taught me more than I have them. After all these years I am still so very grateful for the education.

I am a better person for having known you, XXXX. Thanks for being one of the people who “filled me up” this year!

No longer your teacher, so I’ll just close this as-

Your Friend-

Brian Thornton

****

That's it for now. See you all in two weeks!

As I've written before, my day gig is teaching middle school history. As a middle school teacher (or as a public school teacher at any level, for that matter), I can attest to the importance of the month of June as both a signpost and a destination: a door into another year, another phase of life.

This is especially true for kids moving from middle to high school.

This year the mother of one of my students informed me that every year since her son was in kindergarten she had asked his teacher to write a letter to him at the end of the year. This year he had SIX different teachers (remember, it's middle school): and she chose to ask me because he had told her many times that I was his favorite teacher.

Phew.

Of course I said yes. No small obligation, because (as any teacher can tell you, the end of the school year is BUSY!

I've posted what I came up with below. Not least because we live in a cynical age, and I find the people I work with, the current generation currently coming into their late teens so heartening to be around. I honestly believe these kids are going to save the planet.

Dear XXXX-

I was honored when your mom told me about your family’s tradition of having a teacher write you a letter for every year of school in your life, and asked that I write this year's letter. Not surprising, I guess, that a history teacher would have an appreciation for tradition, right?

One of the reasons I so enjoy teaching 8th grade is that I get to meet young people on the cusp of adulthood–literally in the act of becoming who they are going to be for the rest of their lives. And I am so happy to have met YOU this year. You, Mr. XXXX, are a fine young man. And it has been my pleasure and my honor to serve as your teacher.

You have so much great stuff ahead of you–not just high school, but your entire life–just remember that this journey you’re on is a marathon (the race, not the Greco-Roman battle! HA! Ancient History joke!), not a sprint, and it’s very important that you take a moment every now and again to look around and take it all in. The memories you make this summer, and in high school, will stay with you, and inform and influence the choices you make and the paths you take in the years to come.

With that in mind, try to surround yourself with good people. We meet all kinds of folks in life- those who fill you up? Try to keep them around. Those who wear you out? Let them go. You’re possessed of a giving nature and a good heart, XXXX- and you deserve to get that back from the people in your life.

Most of all, please remember to be as good to yourself as you are to others. And like I said before, take the time to enjoy this life while you’re living it!

Nearly lastly, please thank your parents for me. First, for sending you to us here at XXXXXXXX, and second for asking that I write you this letter.

And lastly, THANK YOU for everything you’ve done this year. I always end the school year feeling as if my students have taught me more than I have them. After all these years I am still so very grateful for the education.

I am a better person for having known you, XXXX. Thanks for being one of the people who “filled me up” this year!

No longer your teacher, so I’ll just close this as-

Your Friend-

Brian Thornton

****

That's it for now. See you all in two weeks!

26 June 2019

The Art of Memory

My pal Keith McIntosh was thinking out loud the other day, that when you're in the library, or a brick-and-mortar bookstore, and you go looking for something, you often find something associated - or even unassociated - by accident. He's not the only one to remark on this, of course, but Keith was wondering why virtual shopping can't be organized in a similar way.

Amazon will show you other stuff you've shopped for or searched out recently, or stuff their algorithm suggests based on your purchase history, but it's market-driven. What about serendipity? You could be looking up the Tudors in the European history section, and stumble on some little-known thing about the Mongols, two shelves over. Same goes for learning basic crochet techniques, or high-altitude baking. It is possible to use the Dewey decimal system, say, to replicate the physical feel of shelves in digital. Or a visual, an imaginary bookstore that somehow leaves room for the accidental. I'm sure someone's thought of it before, and the question is execution: How do you design for the random, or peripheral vision? Engineering logic is linear, it's designed to filter out, to recognize pattern limits, not intuit a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

As it happens, I was re-reading yet again the John Crowley novel Little, Big, first published in 1981 and just as heartbreaking the fourth or fifth time around. Actually, this is one of those books I read all or part of every couple of years, like Mary Renault's Last of the Wine or Len Deighton's Bomber. As if shrugging into a familiar garment, yes, but always finding some new astonishment. I might be reading for technique - how, exactly, did they pull off such-and-such an effect? - but I invariably wind up getting sucked into the story, and I'm not looking for tips and tricks, I'm steering into the next tight turn. The grace and felicity is all.

Crowley develops an elaborate conceit in his book, the Art of Memory. This is in fact a real thing, the study of mnemonics, going back at least to Pythagoras, and later refined by Giordano Bruno. (Crowley has a long fascination with Bruno.) More recently still, there's the Frances Yates book titled The Art of Memory. I'm giving a sort of potted version of this, but the way Crowley explains it, you build a memory house, and people it with artifacts or avatars. You might set aside a room for Youth, a faded rose or a broken mirror to represent a path not taken, but the objects don't require literal consistency, they don't have to be an actual objective representation, they need only conjure up some specific smell, a taste or a time, a character of something, a suggestion, if only a sketch or a gesture.

Now, supposing this house has many rooms, which you've added as needed, and some of those rooms left behind and the memory objects in them gathering dust - let's imagine we turn an unexpected corner and open a different door into that particular gallery, and see those memory objects back to front, a reversed perspective. Would we catch them unawares, surprised to see us, in a state of undress, so to speak?

In other words, what's two shelves over? Memory tends to repeat. Once we start down a train of thought, if it's well-traveled, we stop at the same stations. It may not be a straight line, but we ricochet off the same surfaces. It's almost certainly a hard-wired function. Maybe it's a protective mechanism. It's an almost impossible habit to break. Not only can we not change our personal history, we can't change how we think about it, or escape.

I'm fascinated by the mechanics Crowley imagines, going into the house of memory by the back stairs, and finding a different way to the front. And as you pass by them, things not quite where they're supposed to be, or not how you thought you left them. The truth is, it's not that we pass this way but once, but that we pass this way again and again, and each time we tell ourselves the same story.

Amazon will show you other stuff you've shopped for or searched out recently, or stuff their algorithm suggests based on your purchase history, but it's market-driven. What about serendipity? You could be looking up the Tudors in the European history section, and stumble on some little-known thing about the Mongols, two shelves over. Same goes for learning basic crochet techniques, or high-altitude baking. It is possible to use the Dewey decimal system, say, to replicate the physical feel of shelves in digital. Or a visual, an imaginary bookstore that somehow leaves room for the accidental. I'm sure someone's thought of it before, and the question is execution: How do you design for the random, or peripheral vision? Engineering logic is linear, it's designed to filter out, to recognize pattern limits, not intuit a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

As it happens, I was re-reading yet again the John Crowley novel Little, Big, first published in 1981 and just as heartbreaking the fourth or fifth time around. Actually, this is one of those books I read all or part of every couple of years, like Mary Renault's Last of the Wine or Len Deighton's Bomber. As if shrugging into a familiar garment, yes, but always finding some new astonishment. I might be reading for technique - how, exactly, did they pull off such-and-such an effect? - but I invariably wind up getting sucked into the story, and I'm not looking for tips and tricks, I'm steering into the next tight turn. The grace and felicity is all.

Crowley develops an elaborate conceit in his book, the Art of Memory. This is in fact a real thing, the study of mnemonics, going back at least to Pythagoras, and later refined by Giordano Bruno. (Crowley has a long fascination with Bruno.) More recently still, there's the Frances Yates book titled The Art of Memory. I'm giving a sort of potted version of this, but the way Crowley explains it, you build a memory house, and people it with artifacts or avatars. You might set aside a room for Youth, a faded rose or a broken mirror to represent a path not taken, but the objects don't require literal consistency, they don't have to be an actual objective representation, they need only conjure up some specific smell, a taste or a time, a character of something, a suggestion, if only a sketch or a gesture.

Now, supposing this house has many rooms, which you've added as needed, and some of those rooms left behind and the memory objects in them gathering dust - let's imagine we turn an unexpected corner and open a different door into that particular gallery, and see those memory objects back to front, a reversed perspective. Would we catch them unawares, surprised to see us, in a state of undress, so to speak?

In other words, what's two shelves over? Memory tends to repeat. Once we start down a train of thought, if it's well-traveled, we stop at the same stations. It may not be a straight line, but we ricochet off the same surfaces. It's almost certainly a hard-wired function. Maybe it's a protective mechanism. It's an almost impossible habit to break. Not only can we not change our personal history, we can't change how we think about it, or escape.

I'm fascinated by the mechanics Crowley imagines, going into the house of memory by the back stairs, and finding a different way to the front. And as you pass by them, things not quite where they're supposed to be, or not how you thought you left them. The truth is, it's not that we pass this way but once, but that we pass this way again and again, and each time we tell ourselves the same story.

25 June 2019

If I Should Die Before I Wake

The recent passing of Sandra Seamans, whose blog “My Little Corner” was a must-visit for every mystery short story writer seeking publication, reminds me once again of how important it is to ensure that our families are aware of our writing lives. They often know little about our on-line and off-line publishing activities, the organizations of which we are members, the editors and publishers with whom we engage, and the many friends—some of whom we have never met outside of social media, blog posts, and email—we have in the writing community.

Obituaries are often written in haste by family members who are grieving, and the literary endeavors of the departed are often of little concern to those mourning the death of a spouse, parent, or child. If mentioned at all, these endeavors are likely glossed over.

Certainly, immediate family members, close friends, and employers get notified. Families of those who were members of churches, synagogues, and mosques likely notify the deceased’s religious leaders and their worship community. But who ensures that the writing community learns of the writer’s passing?

Some of us are lucky. We have spouses who are active participants in our writing lives. They attend conventions with us, invite fellow writers into our homes, have met some of our editors, know to which group blogs we contribute, and know of which professional organizations we are members. Not all of us are so lucky.

Especially for those whose family members are not active participants in our writing lives, but also as an aid to those who are, we should prepare a few important documents. The obvious are a medical power of attorney, a will with a named executor familiar with our literary endeavors (some writers more knowledgeable than I recommend a literary executor in addition to the regular executor), and funeral instructions.

May I also suggest a draft of one’s obituary? I just updated mine, ensuring that my writing life is documented appropriately.

Family members will likely remember to notify employers—for those of us with day jobs—but will they know to notify professional organizations such as the Mystery Writers of America and Private Eye Writers of America? May I suggest a list of organizations in which one is a member, including contact information.

Those left behind will likely not understand our record-keeping systems, so an explanation of how to determine what projects are due and will remain undelivered, what submissions are outstanding, what stories have been accepted for publication but have not yet been published, and what might still be required of accepted stories (copyedits, reviews of page proofs, writing of author bios, and so on).

And then there’s the money. We don’t just receive checks in the mail. We also have regular royalty payments deposited directly into our bank accounts, and we receive both one-time and regular royalty payments via PayPal. Can those left behind access our accounts after our demise, and do they understand the financial loss if they close accounts without ensuring that all regular royalty payments and one-time payments are rerouted to the estate’s accounts?

I’m certain there is much more our families need to know about our writing lives, so forgive me if I’ve failed to mention something important. But just looking at what I’ve already outlined lets me know that I have much to do to prepare my family—and I’m one of the lucky writers whose spouse plays an active role in my writing life.

Guns + Tacos launches next month, and y’all don’t want to miss even a single episode of this killer new serial novella anthology series, created by me and Trey R. Barker and published by Down & Out Books. First up: Gary Phillips with Tacos de Cazuela con Smith & Wesson. Then in August comes my novella Three Brisket Tacos and a Sig Sauer, followed each month thereafter by novellas by Frank Zafiro, Trey R. Barker, William Dylan Powell, and James A. Hearn.

|

| Sandra Seamans |

Certainly, immediate family members, close friends, and employers get notified. Families of those who were members of churches, synagogues, and mosques likely notify the deceased’s religious leaders and their worship community. But who ensures that the writing community learns of the writer’s passing?

Some of us are lucky. We have spouses who are active participants in our writing lives. They attend conventions with us, invite fellow writers into our homes, have met some of our editors, know to which group blogs we contribute, and know of which professional organizations we are members. Not all of us are so lucky.

Especially for those whose family members are not active participants in our writing lives, but also as an aid to those who are, we should prepare a few important documents. The obvious are a medical power of attorney, a will with a named executor familiar with our literary endeavors (some writers more knowledgeable than I recommend a literary executor in addition to the regular executor), and funeral instructions.

May I also suggest a draft of one’s obituary? I just updated mine, ensuring that my writing life is documented appropriately.

Family members will likely remember to notify employers—for those of us with day jobs—but will they know to notify professional organizations such as the Mystery Writers of America and Private Eye Writers of America? May I suggest a list of organizations in which one is a member, including contact information.

Those left behind will likely not understand our record-keeping systems, so an explanation of how to determine what projects are due and will remain undelivered, what submissions are outstanding, what stories have been accepted for publication but have not yet been published, and what might still be required of accepted stories (copyedits, reviews of page proofs, writing of author bios, and so on).

And then there’s the money. We don’t just receive checks in the mail. We also have regular royalty payments deposited directly into our bank accounts, and we receive both one-time and regular royalty payments via PayPal. Can those left behind access our accounts after our demise, and do they understand the financial loss if they close accounts without ensuring that all regular royalty payments and one-time payments are rerouted to the estate’s accounts?

I’m certain there is much more our families need to know about our writing lives, so forgive me if I’ve failed to mention something important. But just looking at what I’ve already outlined lets me know that I have much to do to prepare my family—and I’m one of the lucky writers whose spouse plays an active role in my writing life.

Guns + Tacos launches next month, and y’all don’t want to miss even a single episode of this killer new serial novella anthology series, created by me and Trey R. Barker and published by Down & Out Books. First up: Gary Phillips with Tacos de Cazuela con Smith & Wesson. Then in August comes my novella Three Brisket Tacos and a Sig Sauer, followed each month thereafter by novellas by Frank Zafiro, Trey R. Barker, William Dylan Powell, and James A. Hearn.

Labels:

Frank Zafiro,

Gary Phillips,

Michael Bracken,

Sandra Seamans,

William Dylan Powell,

writers,

writing

24 June 2019

The Times, They Are A-changing

by Steve Liskow

Some time ago, I pointed out that writers have to change with the industry, especially if they're self-pubbed.

About ten years ago, I attended a conference where an agent warned the audience that he and his colleagues wouldn't even look at submissions from writers who had self-published. At that time, prevailing wisdom said writers were self-pubbed because their work couldn't meet industry standards.

Mystery writer Joe Konrath and others disputed that claim, saying they were treated badly by the traditional monopoly and could make more money on their own. That argument gained weight when NYT bestseller Barry Eisler turned down a half-million-dollar advance from his traditional house and began publishing his books himself. It's worth noting that because of his successful track record, Eisler had thousands of followers, an advantage the average writer can't claim.

Everything influences everything else, and sometimes that's not a good thing. Self-publishing continues to grow, and it takes a substantial bite out of traditional sales. Last year, nearly a million self-published books appeared. Even if they each only sold one copy, that's a million books that the Big Five didn't sell, and it affects their bottom line.

Traditional markets have consolidated or disappeared. Since there are fewer paying markets, the remaining ones are swamped, for short stories as well as novels. Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine receives over 1000 submissions a week. Even if you read only the first page, 1000 minutes is over 16 hours, which means the slush pile grows more quickly than the rejection letters can go out.

The numbers hamper novelists, too. There are five independent book stores within thirty miles of my condo, and while they all say they support local writers, they do it by charging fees for shelf space and offering consignment splits that range from generous to usurious. They have two reasons for this.

First, self-pubbed authors won't offer the same 60% discount and free shipping and returns for a full refund that traditional publishers do. Bookstores need that break...unless they can stage an event that guarantees lots of sales. If it rains, snows, is too hot, or another event nearby falls on the same day, audience may not show up. a large audience doesn't mean large sales anyway.

Second, traditional publishers take manuscripts that have already been vetted by an agent and will edit them professionally, maybe more than once. It's no longer true that all self-pubbed books are terrible (see Eisler, above), but the only way to find the good ones is to read them. How long would you need to read one million pages to make your choice?

Most libraries follow the same reasoning. I offer a discount and free delivery for libraries that order several of my books, but few accept my offer because their guidelines in the face of annual budget cuts insist they focus on Lee Child and Stephen King because they know the demand is there. It makes sense, but it deprives the patrons of finding new authors to enjoy.

I suggest to those libraries that they buy digital copies of my work because the price is lower and people can borrow several copies simultaneously. That's not making headway either, but I'm trying to offer more options so my work gets read. Besides, if more people read my stuff, I might get more workshop gigs. Those have tapered off because of those same budget cuts. I'm finding new venues and splitting fees, but nobody is making out like Charlie Sheen here.

If your book is on a shelf somewhere, it needs an eye-catching cover. My cover designer does brilliant work. He's also my largest set expense, and I'm not selling enough books at events to break even.

More change...More adjustments...

My next novel, due out at the end of this year, will probably be my last paper book.

I have four stories at various markets and four more in progress. By the end of the year, I may be releasing the unsold stories in digital format. I'm studying GIMP so I can design my own covers.

When you're a writer, you always live in interesting times.

What are you doing differently now?

About ten years ago, I attended a conference where an agent warned the audience that he and his colleagues wouldn't even look at submissions from writers who had self-published. At that time, prevailing wisdom said writers were self-pubbed because their work couldn't meet industry standards.

Mystery writer Joe Konrath and others disputed that claim, saying they were treated badly by the traditional monopoly and could make more money on their own. That argument gained weight when NYT bestseller Barry Eisler turned down a half-million-dollar advance from his traditional house and began publishing his books himself. It's worth noting that because of his successful track record, Eisler had thousands of followers, an advantage the average writer can't claim.

Everything influences everything else, and sometimes that's not a good thing. Self-publishing continues to grow, and it takes a substantial bite out of traditional sales. Last year, nearly a million self-published books appeared. Even if they each only sold one copy, that's a million books that the Big Five didn't sell, and it affects their bottom line.

Traditional markets have consolidated or disappeared. Since there are fewer paying markets, the remaining ones are swamped, for short stories as well as novels. Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine receives over 1000 submissions a week. Even if you read only the first page, 1000 minutes is over 16 hours, which means the slush pile grows more quickly than the rejection letters can go out.

The numbers hamper novelists, too. There are five independent book stores within thirty miles of my condo, and while they all say they support local writers, they do it by charging fees for shelf space and offering consignment splits that range from generous to usurious. They have two reasons for this.

First, self-pubbed authors won't offer the same 60% discount and free shipping and returns for a full refund that traditional publishers do. Bookstores need that break...unless they can stage an event that guarantees lots of sales. If it rains, snows, is too hot, or another event nearby falls on the same day, audience may not show up. a large audience doesn't mean large sales anyway.

Second, traditional publishers take manuscripts that have already been vetted by an agent and will edit them professionally, maybe more than once. It's no longer true that all self-pubbed books are terrible (see Eisler, above), but the only way to find the good ones is to read them. How long would you need to read one million pages to make your choice?

Most libraries follow the same reasoning. I offer a discount and free delivery for libraries that order several of my books, but few accept my offer because their guidelines in the face of annual budget cuts insist they focus on Lee Child and Stephen King because they know the demand is there. It makes sense, but it deprives the patrons of finding new authors to enjoy.

I suggest to those libraries that they buy digital copies of my work because the price is lower and people can borrow several copies simultaneously. That's not making headway either, but I'm trying to offer more options so my work gets read. Besides, if more people read my stuff, I might get more workshop gigs. Those have tapered off because of those same budget cuts. I'm finding new venues and splitting fees, but nobody is making out like Charlie Sheen here.

If your book is on a shelf somewhere, it needs an eye-catching cover. My cover designer does brilliant work. He's also my largest set expense, and I'm not selling enough books at events to break even.

More change...More adjustments...

My next novel, due out at the end of this year, will probably be my last paper book.

I have four stories at various markets and four more in progress. By the end of the year, I may be releasing the unsold stories in digital format. I'm studying GIMP so I can design my own covers.

When you're a writer, you always live in interesting times.

What are you doing differently now?

Labels:

markets,

novels,

self-publishing,

short stories,

Steve Liskow

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

23 June 2019

When Showing Tells

by Leigh Lundin

Addicted to the Hard Stuff

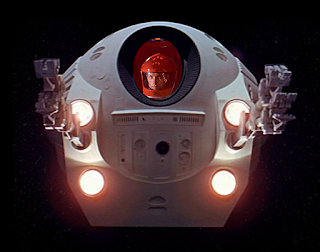

From about age eight, I devoured science fiction with a passion. If I’d read Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The Sentinel’ then, I didn’t recall. Certainly I wouldn’t have guessed it would inspire arguably the finest science fiction film of the past half century. I didn’t make the connection at the time.

Nothing was going to stop this impecunious Greenwich Village student from seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey. For one thing, few critics and even fewer directors understand ‘hard science’ fiction. Those meager numbers unsurprisingly thin as a shrinking percentage of the populace take science itself seriously.

Back in April 1968, articles and advance marketing drove the buzz in New York City. Writers droned on and on about the beauty of the space ballet. Computer trade journals discussed the technology of HAL. Gossip columnists debated how to pronounced the lead actor’s name. New York’s theatre scene gushed that the chimps were portrayed by dancers. Much later we’d learn they were acted out by professional mimes.

Within days, the excited film talk turned to disillusion and disappointment. Even SF fans emerged from the premier saying, “Huh?”

WTF?

Foremost, the original cut fell victim to that movie-goer tendency to rush from a theatre before the first credit rolls. (The credits stampede has become such an annoying phenomenon that some directors reward fans who sit through until the end with further scenes.) Back then, fatigued by 2001’s seemingly endless ‘acid trip’, theatres emptied moments before the crux of the story revealed itself. Audiences missed the entire point of the story.

Stanley Kubrick sliced and diced the ‘acid trip’ (now called ‘star gate’) and reworked the production’s final few minutes. Even so, readers had to wait for Clarke to finish the novel written in parallel to piece together the entire affair. Clarke’s earlier 1948/1951 short story wouldn’t prove helpful at all.

Down the Wrong Path

As a penniless student, I refused to miss a second of the film’s original two hours, forty minutes. Although I remained through the ending, I left confused for a different reason. Not until the book came out did I realize a common story-telling technique misled me:

To demonstrate I wasn’t the only person led astray, I quote Wikipedia:

That happened, but that’s not what happened. To flesh in more detail:

That key led some to a false conclusion:

The monolith triggered violence and aggression.

The writers had intended the scene to show:

The monolith precipitated evolution.

No one knows how many viewers interpreted the scene wrongly. Between that problem and the abortive rush-out-the-door ending, Kubrick and Clarke managed to confuse an entire city and probably an entire nation.

Afterword

I hazard the filmmakers became blinded by proximity– they’d grown too close to that vignette to realize it could lead to misunderstanding. A fix could have been easy.

Afterward

Nonetheless, I love 2001. Revisions have clarified and far more answers are available now than on opening day.

Months later, I would see another of my favorites in that same theatre district, Silent Running. About the same time while still on a student budget, a faded poster lured me to spend a couple of hours in a drab Greenwich Village dollar theatre, an elephant graveyard of soon-to-be-forgotten films. Filmed on a shoestring budget, that obscure celluloid strip turned out a gem in the rough. THX-1138 was the product of an unknown 24-year-old writer/director… George Lucas.

Arthur C Clarke’s short story? After seventy years, it shows its age, but it’s worth reading. We’re pleased to bring you ‘The Sentinel’ PDF and MP3/M4B audiobooks. You can also read or listen to 2001: A Space Odyssey provided for free by the thoughtful people at BookFrom.net. To listen or download, don't be misled by the nearby ‘Text-to-Speech’ icon, but click on the Listen 🔊 link in the upper right corner of the page.

From about age eight, I devoured science fiction with a passion. If I’d read Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The Sentinel’ then, I didn’t recall. Certainly I wouldn’t have guessed it would inspire arguably the finest science fiction film of the past half century. I didn’t make the connection at the time.

Nothing was going to stop this impecunious Greenwich Village student from seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey. For one thing, few critics and even fewer directors understand ‘hard science’ fiction. Those meager numbers unsurprisingly thin as a shrinking percentage of the populace take science itself seriously.

Back in April 1968, articles and advance marketing drove the buzz in New York City. Writers droned on and on about the beauty of the space ballet. Computer trade journals discussed the technology of HAL. Gossip columnists debated how to pronounced the lead actor’s name. New York’s theatre scene gushed that the chimps were portrayed by dancers. Much later we’d learn they were acted out by professional mimes.

Within days, the excited film talk turned to disillusion and disappointment. Even SF fans emerged from the premier saying, “Huh?”

WTF?

Foremost, the original cut fell victim to that movie-goer tendency to rush from a theatre before the first credit rolls. (The credits stampede has become such an annoying phenomenon that some directors reward fans who sit through until the end with further scenes.) Back then, fatigued by 2001’s seemingly endless ‘acid trip’, theatres emptied moments before the crux of the story revealed itself. Audiences missed the entire point of the story.

Stanley Kubrick sliced and diced the ‘acid trip’ (now called ‘star gate’) and reworked the production’s final few minutes. Even so, readers had to wait for Clarke to finish the novel written in parallel to piece together the entire affair. Clarke’s earlier 1948/1951 short story wouldn’t prove helpful at all.

Down the Wrong Path

As a penniless student, I refused to miss a second of the film’s original two hours, forty minutes. Although I remained through the ending, I left confused for a different reason. Not until the book came out did I realize a common story-telling technique misled me:

Showing, Not Telling

To demonstrate I wasn’t the only person led astray, I quote Wikipedia:

| “ | In an African desert millions of years ago, a tribe of hominids is driven away from its water hole by a rival tribe. They awaken to find a featureless black monolith has appeared before them. Seemingly influenced by the monolith, they discover how to use a bone as a weapon and drive their rivals away from the water hole. | ” |

|---|

That happened, but that’s not what happened. To flesh in more detail:

| Following the unveiling of the monolith, these ancestral apes take up long bones as clubs. In a slow-motion orgy of destruction, they bash discarded skulls into shards. In the next scene, they enthusiastically wield clubs to kill their hated enemies. |

That key led some to a false conclusion:

The monolith triggered violence and aggression.

The writers had intended the scene to show:

The monolith precipitated evolution.

No one knows how many viewers interpreted the scene wrongly. Between that problem and the abortive rush-out-the-door ending, Kubrick and Clarke managed to confuse an entire city and probably an entire nation.

Afterword

I hazard the filmmakers became blinded by proximity– they’d grown too close to that vignette to realize it could lead to misunderstanding. A fix could have been easy.

- The primates drive away sabre-tooth tigers or woolly mammoths, not a warring primate clan.

- The primates learn to dig, devise, or divert water using their evolving brains, not brawn.

Afterward

Nonetheless, I love 2001. Revisions have clarified and far more answers are available now than on opening day.

Months later, I would see another of my favorites in that same theatre district, Silent Running. About the same time while still on a student budget, a faded poster lured me to spend a couple of hours in a drab Greenwich Village dollar theatre, an elephant graveyard of soon-to-be-forgotten films. Filmed on a shoestring budget, that obscure celluloid strip turned out a gem in the rough. THX-1138 was the product of an unknown 24-year-old writer/director… George Lucas.

Arthur C Clarke’s short story? After seventy years, it shows its age, but it’s worth reading. We’re pleased to bring you ‘The Sentinel’ PDF and MP3/M4B audiobooks. You can also read or listen to 2001: A Space Odyssey provided for free by the thoughtful people at BookFrom.net. To listen or download, don't be misled by the nearby ‘Text-to-Speech’ icon, but click on the Listen 🔊 link in the upper right corner of the page.

Labels:

2001,

Arthur C. Clarke,

Leigh Lundin,

lessons,

writing

22 June 2019

Ten Minutes of Comedy at the Arthur Ellis Awards Gala (and they even let me stay on stage...)

The Crime Writers

of Canada went loco, and asked me to emcee the Arthur Ellis Awards this

year. Somehow they learned I might have

done standup in the past. Or maybe not,

because they even paid me. It may be

more than my royalties this quarter.

I dug back into

my Sleuthsayer files to decide what might appeal to a hardened (read soused)

group of crime writers en mass, with an open bar. This is what resulted, and I’m happy to say

the applause was generous. You may

remember some of this.

Arts and Letters

Club, Toronto, May 23, 2019, 9PM

Hello! Mike said I could do a few minutes of comedy

this evening as long as I apologized in advance.

My name is

Melodie Campbell, and it’s my pleasure to welcome here tonight crime writers,

friends and family of crime writers, sponsors, agents, and any publishers still

left out there.

Tonight is that

special night when the crime writing community in Canada meets to do that one

thing we look forward to all year: which

is get together and bitch about the industry.

Many of you knew

my late husband Dave. He was a great

supporter of my writing, and of our crime community in general. But many times, he could be seen wandering

through the house, shaking his head and muttering “Never Marry a crime writer.”

I’ve decided,

here tonight, to list the reasons why.

Everybody knows

they shouldn’t marry a crime writer.

Mothers the world over have made that obvious: “For Gawd Sake, never

marry a marauding barbarian, a sex pervert, or a crime writer.” (Or a

politician, but that is my own personal bias.

Ignore me.)

But for some

reason, lots of innocent, unsuspecting people marry authors every year. Obviously, they don’t know about the

“Zone.” (More obviously, they didn’t

have the right mothers.)

Never mind: I’m

here to help.

I think it pays

to understand that crime writers aren’t normal humans: they write about people

who don’t exist and things that never happened.

Their brains work differently.

They have different needs. And in

some cases, they live on different planets (at least, my characters do, which

is kind of the same thing.)

Thing is, authors

are sensitive creatures. This can be

attractive to some humans who think that they can ‘help’ poor writer-beings (in

the way that one might rescue a stray dog.)

True, we are easy to feed and grateful for attention. We respond well to praise. And we can be adorable. So there are many reasons you might wish to

marry a crime writer, but here are 10 reasons why you shouldn’t:

The basics:

1 Crime Writers are hoarders. Your house will be filled with books. And more books. It will be a shrine to books. The lost library of Alexandria will pale in

comparison.

2 Crime Writers are addicts. We mainline coffee. We’ve also been known to drink other

beverages in copious quantities, especially when together with other writers in

places called ‘bars.’

3 Authors are weird. Crime Writers are particularly weird (as

weird as horror writers.) You will hear all sorts of gruesome research details

at the dinner table. When your parents

are there. Maybe even with your parents

in mind.

4 Crime Writers are deaf. We can’t hear you when we are in our offices,

pounding away at keyboards. Even if you come in the room. Even if you yell in our ears.

5 Crime Writers are single-minded. We think that spending perfectly good

vacation money to go to conferences like Bouchercon is a really good idea. Especially if there are other writers there

with whom to drink beverages.

And here are some worse reasons why you

shouldn’t marry a crime writer:

6 It may occasionally seem that we’d rather

spend time with our characters than our family or friends.

7 We rarely sleep through the night. (It’s hard to sleep when you’re typing. Also, all that coffee...)

8 Our Google Search history is a thing of

nightmares. (Don’t look. No really – don’t. And I’m not just talking about ways to avoid

taxes… although if anyone knows a really fool-proof scheme, please email me.)

And the really

bad reasons:

9 If we could have affairs with our beloved

protagonists, we probably would. (No!

Did I say that out loud?)

10 And lastly, We know at least twenty ways to

kill you and not get caught.

RE that last

one: If you are married to a crime

writer, don’t worry over-much. Usually

crime writers do not kill the hand that feeds them. Most likely, we are way too focused on

figuring out ways to kill our agents, editors, and particularly, reviewers.

Finally, it seems appropriate to finish with the first joke I ever sold, way back in the 1990s:

Recent studies show that approximately 40% of writers are manic depressive. The rest of us just drink.

Melodie Campbell can be found with a bottle of Southern Comfort in the True North. You can follow her inane humour at www.melodiecampbell.com

Labels:

Arthur Ellis,

awards,

Canada,

comedy,

crime,

crime writers,

humor,

humour,

publishers,

writers,

writing

21 June 2019

Power Pop with a Bullet –S.W. Lauden's That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist

|

| That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist |

On the other side of the dial is punk rock, the world that author S.W. Lauden traverses in his Gary Salem punk PI trilogy of novels. Lauden switches stations and embraces the best of rock's most melancholy medium in his newly released novelette, That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist. It's a tale of rock 'n' roll redemption, a crime story that explores power pop's yearning and burning while cranking up the suspense.

Brothers (and bandmates) Jack and Jamie Sharp's heist of $100,000-worth of vintage guitars would've been a success if Jack hadn't stopped to strum a sweet '59 Les Paul Standard. Instead, Jack got busted, Jamie got the guitars, and their band is tossed in the dollar bin indefinitely. That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist opens three years later as Jack steps out of the Oklahoma State Pen on parole, looking to get his $50,000 cut of the burglary. He's packing heat in case anyone, including family, stands in his way.

Jack is too much of a badass to admit it, but he's also bugged that neither Jamie nor his little sister Jenna came to visit him while he was locked up. This familial diss picks at a long-festering wound in Jack's soul: Jack's father abandoned the family, without explanation, when Jack was twelve.

|

| S.W. Lauden dares you to say no to more cowbell. |

Power pop, a passion for both brothers, is a non-stop topic of conversation for the Sharps. It's a way the brothers (and the reader, if you remember the '70s) can reference their common past. It's also the novelette's perpetual, handcrafted soundtrack. Unlike the mindless hedonism of the worst of arena rock (there's more than one way to rock, Sammy-a lot more), power pop often invokes yearning, loss, and melancholy. The music plays out-loud the feelings that Jack, forced since childhood to be tough-as-nails, can never openly express. It's a brilliant device, like a Greek chorus amplified through a Fender Bassman.

|

| 20/20's debut album |

Fans of power pop, reading to see to see if their fav bands are mentioned, won't be disappointed.

How about the highly underrated 20/20, who had a minor hit with "My Yellow Pills"?

They're in.

The tragically doomed Bad Finger?

In.

Big Star, adored by critics, ruined by their record label?

In.

|

| The Bob's Big Boy Beatle Booth plaque. From The Maddox Archives |

I feel That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist was tailor-made for me. I've been in bands, slowed down vinyl to learn guitar solos, and consider Lester Bangs a twentieth century giant. I still get a pang of excitement when I'm seated at the Beatles Booth at the Toluca Lake Bob's Big Boy, a corner section where John, Paul, George and Ringo (power-pop godfathers) sat in the summer of '65.

|

| Raspberries give you one of rock's greatest 45s. |

I love crime fiction where bad deeds are just a shadow play of bigger issues at work; issues like personal reckoning and, as is the case here, family reconciliation (or lack thereof). Ross McDonald made a brilliant career of this, and his best work reads like mini-Greek tragedies. Lauden offers an alternative, a song of hope for the broken and abandoned. Jack may never get the payback he wants, but you'll root for him to get the family he deserves. Easily a one-sitting read, That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist is power pop with a bullet, and will shoot to the top of your playlist.

Two of my favorite topics of conversation are rock music and crime fiction. S.W. Lauden lives and breathes both, so naturally I had a few questions.

Lawrence Maddox: Punk is key to your Greg Salem PI trilogy. Greg is a detective by day, and in a punk band by night. Was it hard going from punk to power pop?

|

| The Greg Salem punk PI trilogy |

Then, in the midst of doing research on the history of power pop, I read about this super rare single by the pre-Beatles band called The Quarrymen (featuring Paul McCartney, George Harrison and John Lennon–among others–covering the Buddy Holly song). That's when my crime writer brain kicked in.

LM: Your fictional band Bad Citizens Corporation (from the Greg Salem trilogy) also began as a band of brothers. Why is brotherhood an important theme for you?

|

| The original line-up of The Kinks in 1965. Pete Quaife, Dave Davies, Ray Davies, Mick Avory. |

Secondly, I had older brothers growing up who were musicians (a bass player and a guitarist) who started a heavy metal band when they were in high school (and I was in elementary school). The original reason I chose drums as an instrument was so I could join their band one day (never happened–single tear).

Third, the brothers in the Greg Salem punk rock PI novels and Jack and Jamie in That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist are their own characters, but they're also two extremes of my own personality–one is more self-loathing/self-destructive and the other is more of an egomaniac.

I feel emotionally drained. Happy now?

|

| Keith Morris' autobiography My Damage. |

SWL: How much time do you have?

Speaking of The Kinks, I just read Ray Davies' batshit crazy autobiography from the 90s, X-Ray. I loved it. I also recently read Boys Don't Lie about the Zion, Illinois power pop band The Shoes (power pop royalty and a band featuring brothers!), and A Man Called Destruction about Alex Chilton. I loved Trouble Boys about The Replacements (the Stinson brothers!), as well as John Doe and Tom DeSavia's book about the original LA punk scene, Under the Big Black Sun. What else?

The Closer You Are, about Robert Pollard and Guided By Voices, was pretty great. So was The Beastie Boys Book, and the 33 1/3 book about Big Star's Radio City. A super weird one that I highly recommend is Supernatural Strategies for Making a Rock 'n' Roll Group by Ian Svenonius. That one's in a category all its own.

|

| S.W. Lauden recording for The Brothers Steve. That's a Murder & Mayhem t-shirt btw. |

SWL:Well, they say write what you know...

I just played drums on an album with an LA-based garage rock/power pop band called The Brothers Steve. It's the first full-length album I've played on in a few years. The self-released vinyl comes out in late July, but a few songs will pop up here and there before then. And we're playing at Molly Malone's in Los Angeles on Saturday, July 27, as part of the International Pop Overthrow festival. Good times.

That'll Be the Day: A Power Pop Heist is available on Amazon. As mentioned earlier, S.W. Lauden is the author of the Greg Salem punk PI trilogy (Bad Citizen Corporation, Grizzly Season and Hang Time). His Tommy & Shayna novellas include Crosswise and Crossbones. S.W. Lauden is the pen name for Steve Coulter, drummer for Tsar and The Brothers Steve. Check him out at swlauden.com.

I'm the author of Fast Bang Booze (Shotgun Honey). Publishers Weekly said "Fans of offbeat noir will have fun." I'm currently working on the sequel.

I'm the author of Fast Bang Booze (Shotgun Honey). Publishers Weekly said "Fans of offbeat noir will have fun." I'm currently working on the sequel.Want to discuss power pop to punk? The secret behind Bob's Chili Spaghetti? Come hang out at the Beatles Booth or find me on Twitter, LawrenceMaddox@madxbooks.

20 June 2019

Ancestry and Me

by Eve Fisher

by Eve Fisher

As many of you, beloved readers, know, I was adopted to this country from Greece back when I was 2 1/2 years old, and have lived here ever since. I was naturalized by my parents when I was five. I was told I was adopted when I was about ten, and I took it better than you might expect. For one thing, I was starting to grasp that my red-haired, Scotch-Irish, blue-eyed mother was probably not a direct genetic link. (Still not sure about Daddy, but that's another story...) For another, things were already getting strange in the Velissarios household, and - eventually - it was good to know I didn't have to be like that. It wasn't in my gene pool.

As many of you, beloved readers, know, I was adopted to this country from Greece back when I was 2 1/2 years old, and have lived here ever since. I was naturalized by my parents when I was five. I was told I was adopted when I was about ten, and I took it better than you might expect. For one thing, I was starting to grasp that my red-haired, Scotch-Irish, blue-eyed mother was probably not a direct genetic link. (Still not sure about Daddy, but that's another story...) For another, things were already getting strange in the Velissarios household, and - eventually - it was good to know I didn't have to be like that. It wasn't in my gene pool.

But, inevitably, the question arises, what is? Other than thalassemia minor and arthritis?

Now growing up, I'd been told three different stories about how I'd ended up in the orphanage.

Anyway, a few years after my parents died, I thought I'd look into it. There were a couple of reasons why I finally decided to do this:

(1) I finally had all the adoption documents which my father had saved but never let me see before. Included: a Certificate that I "was taken over by the Athens Municipal Foundling Home of Athens on the 6th of July, 1955, and entered into our records under register serial number 44627." (We will be coming back to this.)

(2) Loneliness. You see, my parents had successively cut themselves off, through travel (when we moved to California, my father never contacted any of his relatives in NYC again), quarrels (my mother and her only brother didn't speak for the last 20 years of their lives), and a general indifference to family which I've never understood. And that cut me off too. Plus I'd done quite a bit of moving myself. The end result was that somewhere in my 50s I realized that the only family I had was my husband and friends -

But I felt like I was standing on the end of a thin wedge of rock hanging over an abyss. So, being me, I decided to try to do something about it. The research began.

And the first thing I found was a number of news stories about black market adoptions from Greece to America back in the 1950s. (See New York Times, LA Times, and many more; just Google Greek black market adoption.)

Basically, what happened is that a very poor post-war Greece figured out that they could make a lot of money from selling babies to Americans. And they were stealing them from poor Greek families - telling the mothers of twins that one of them had died in childbirth, or that their baby had died, period, or just taking them - and then laundering the babies through places like the Thessaloniki Orphanage or the Athens Municipal Foundling Home. And then selling them to desperate American families for $1,000 and up (which back in the 1950s was a fairly large sum of money). And telling the Americans back-stories about their new little toddlers like her biological parents died in an earthquake. And giving almost all the little girl toddlers the same damn name as is on my original Greek passport: Mariana. (Emphasis mine.)

Well, after I gasped for a while like a fish on the bottom of a boat, I went to one of the websites that existed to reunite [perhaps] black-market adoptees with their birth mothers, and began the process. It was all remarkably swift, and did not end happily. I never spoke or wrote directly to my supposed birth mother; instead it was filtered through an intermediary. At the end, I sent photos of myself in the orphanage and now. The last response I got was "That is not my child. Leave me alone."

And so I have. Thinking back on it all, I don't know if any of it was true or not. Whether the woman who did the search was actually in contact with anyone, or just answering out of her own head, for some obscure reason. (No money exchanged hands, which makes it even weirder.) Whether the supposed biological mother told the truth - she lost a child, but it wasn't me - or if she was lying because she did not want me back in her life.

But I never reopened that can of worms. Instead, I moved on to the next one: Genetics.

My first genetics test was with National Geographic Genographic Project, and the results were that I was 53% Greek, 24% Tuscan Italian, and 21% Northern (Asian) Indian. It was the last that surprised me - Greeks and Italians have commingled for millennia, but what ancestor picked up a Kashmiri bride/groom? Although it might have occurred back at the same time that my ancestors - a randy lot - were commingling with any hominid they could find. My genome is 3% Neanderthal, 3.7% Denisovian, and 93.3% Cro-magnon, and if you'll look at the "Evolution and Geographic Spread of Denisovians" map above, you'll see what I'm talking about.

But that wasn't good enough. As the lady said - and I hesitate to repeat it here, for fear of giving Stephen Miller more evil ideas - "Just because you were in a Greek orphanage does not mean that you are Greek." I told her I had a DNA test, but she was not interested in that. Only the names of the biological father and mother would do. I asked how orphans were supposed to come up with that information when they had been abandoned at an orphanage? Not her problem. What about the fact that apparently the Greek government had jurisdiction enough to sell me off for adoption and ship me overseas? Irrelevant. I finally asked her if that meant that Greek orphans in Greece had to apply for citizenship when they came of age, and at that point the conversation came to an end. She suggested that if I had a problem with it, I should get a Greek lawyer, in Greece, and pursue it. So there you go. The ultimate Catch-22 for orphans, and how appropriate for the @#$^&! age we live in.

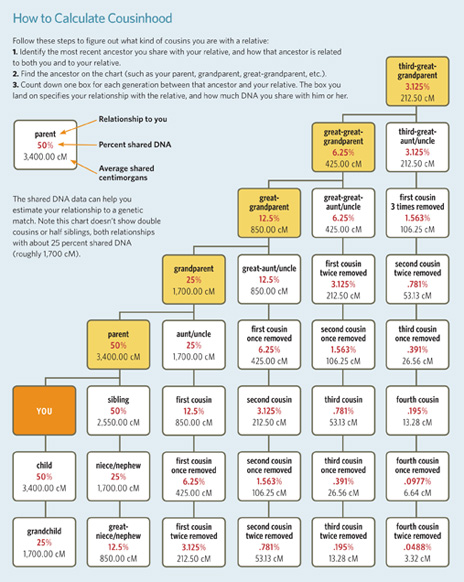

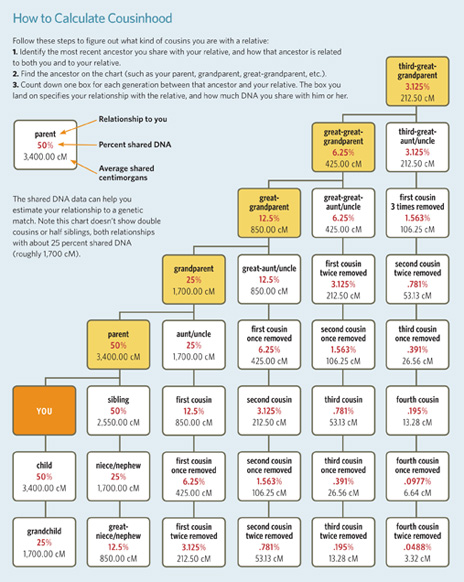

So, after that, I thought, what the hell, I'll do Ancestry.com's DNA test because they match you up with genetic relatives as well as the general heritage. First off, they disagreed with National Geographic: according to them, I'm 85% Greek/Balkan, and only 13% Italian. The rest is kind of vague... But here's the kicker. I went to the list of DNA matches... and I have none. The closest I get is a short list of people who might be my 4th to 6th cousins. What this means - looking at the chart below - is that while we might have crossed paths at an airport, no living relatives have shared bread, wine, or talk for probably 100 years.

My first reaction was that I was like a fox, looking for a hole in a fox hunt, and all the earths are stopped.

My second, was that I was back on that effing wedge of rock.

My third was that the universe was being very clear, and while I didn't like it, I was going to have to accept it.

And then, as Mr. Edwards said to Dr. Johnson, "Cheerfulness breaks in."

I called a dear friend of mine and told her the latest, and she said, "Oh my God! You really are an alien! You really are from some other planet!" And we laughed our heads off.

So, now I have decided to embrace the truth: Sometime after the Neanderthal/ Denisovian encounter, or at the latest after the little trip to the Kashmiri serai, my gene pool carriers took off somewhere else. And then - after some trouble in that particular space-time continuum - dropped me off at the Athens Municipal Foundling Home. Or so they say...

Will keep you posted. Oh, and if anyone out there knows who the little girl below used to be, please let me know.

As many of you, beloved readers, know, I was adopted to this country from Greece back when I was 2 1/2 years old, and have lived here ever since. I was naturalized by my parents when I was five. I was told I was adopted when I was about ten, and I took it better than you might expect. For one thing, I was starting to grasp that my red-haired, Scotch-Irish, blue-eyed mother was probably not a direct genetic link. (Still not sure about Daddy, but that's another story...) For another, things were already getting strange in the Velissarios household, and - eventually - it was good to know I didn't have to be like that. It wasn't in my gene pool.

As many of you, beloved readers, know, I was adopted to this country from Greece back when I was 2 1/2 years old, and have lived here ever since. I was naturalized by my parents when I was five. I was told I was adopted when I was about ten, and I took it better than you might expect. For one thing, I was starting to grasp that my red-haired, Scotch-Irish, blue-eyed mother was probably not a direct genetic link. (Still not sure about Daddy, but that's another story...) For another, things were already getting strange in the Velissarios household, and - eventually - it was good to know I didn't have to be like that. It wasn't in my gene pool.But, inevitably, the question arises, what is? Other than thalassemia minor and arthritis?

Now growing up, I'd been told three different stories about how I'd ended up in the orphanage.

|

| Me, in the orphanage, looking as happy as I was going to get. |

- The first one was that there had been an earthquake in my home town of Karditsa, my parents had died in it, and I - plucky little orphan that I was - was found in the rubble.

- The second was that I was illegitimate, and my biological mother had to put me in the orphanage because in 1950s Greece, there were no decent unmarried mothers. (This sounded more real than the last one.)

- The third was that there was a female relative of my father's family who'd gotten in trouble, and I ended up in the orphanage.

Anyway, a few years after my parents died, I thought I'd look into it. There were a couple of reasons why I finally decided to do this:

(1) I finally had all the adoption documents which my father had saved but never let me see before. Included: a Certificate that I "was taken over by the Athens Municipal Foundling Home of Athens on the 6th of July, 1955, and entered into our records under register serial number 44627." (We will be coming back to this.)

(2) Loneliness. You see, my parents had successively cut themselves off, through travel (when we moved to California, my father never contacted any of his relatives in NYC again), quarrels (my mother and her only brother didn't speak for the last 20 years of their lives), and a general indifference to family which I've never understood. And that cut me off too. Plus I'd done quite a bit of moving myself. The end result was that somewhere in my 50s I realized that the only family I had was my husband and friends -

AND I AM EXTREMELY GRATEFUL FOR EACH AND EVERY ONE OF YOU!!!!

But I felt like I was standing on the end of a thin wedge of rock hanging over an abyss. So, being me, I decided to try to do something about it. The research began.

And the first thing I found was a number of news stories about black market adoptions from Greece to America back in the 1950s. (See New York Times, LA Times, and many more; just Google Greek black market adoption.)

Basically, what happened is that a very poor post-war Greece figured out that they could make a lot of money from selling babies to Americans. And they were stealing them from poor Greek families - telling the mothers of twins that one of them had died in childbirth, or that their baby had died, period, or just taking them - and then laundering the babies through places like the Thessaloniki Orphanage or the Athens Municipal Foundling Home. And then selling them to desperate American families for $1,000 and up (which back in the 1950s was a fairly large sum of money). And telling the Americans back-stories about their new little toddlers like her biological parents died in an earthquake. And giving almost all the little girl toddlers the same damn name as is on my original Greek passport: Mariana. (Emphasis mine.)

Well, after I gasped for a while like a fish on the bottom of a boat, I went to one of the websites that existed to reunite [perhaps] black-market adoptees with their birth mothers, and began the process. It was all remarkably swift, and did not end happily. I never spoke or wrote directly to my supposed birth mother; instead it was filtered through an intermediary. At the end, I sent photos of myself in the orphanage and now. The last response I got was "That is not my child. Leave me alone."

And so I have. Thinking back on it all, I don't know if any of it was true or not. Whether the woman who did the search was actually in contact with anyone, or just answering out of her own head, for some obscure reason. (No money exchanged hands, which makes it even weirder.) Whether the supposed biological mother told the truth - she lost a child, but it wasn't me - or if she was lying because she did not want me back in her life.

But I never reopened that can of worms. Instead, I moved on to the next one: Genetics.

|

| John D. Croft at English Wikipedia |

My first genetics test was with National Geographic Genographic Project, and the results were that I was 53% Greek, 24% Tuscan Italian, and 21% Northern (Asian) Indian. It was the last that surprised me - Greeks and Italians have commingled for millennia, but what ancestor picked up a Kashmiri bride/groom? Although it might have occurred back at the same time that my ancestors - a randy lot - were commingling with any hominid they could find. My genome is 3% Neanderthal, 3.7% Denisovian, and 93.3% Cro-magnon, and if you'll look at the "Evolution and Geographic Spread of Denisovians" map above, you'll see what I'm talking about.

BTW, I am inordinately proud of my alternate hominid ancestry. For one thing, it explains my unusual ability to spot wildlife wherever I go. I was also pretty darn good at tracking before my knees gave out. Plus I'm a great believer in diversity. In my book, if all you've ever known is one thing - you're missing out.And then there's the story about the Greek Consulate. At one point, I was thinking about going to Greece and searching, so I wanted to know a few things, like how long can you stay in Greece without them kicking you out and do I still have Greek citizenship? After all, I still have the Greek passport that I came in with (along with a vintage TWA bag from 1957 that I have been offered serious money for). So I was talking to them about this, and they said that it was just a travel passport, but did not prove my citizenship. And, to confirm whether or not I was a Greek citizen, they would need the names of my biological father and mother. I explained that I was an orphan, and I had been in the Athens Municipal Foundling Home. That I had all the paperwork from the adoption and would be happy to FAX that to them, including the above-referenced Certificate.

But that wasn't good enough. As the lady said - and I hesitate to repeat it here, for fear of giving Stephen Miller more evil ideas - "Just because you were in a Greek orphanage does not mean that you are Greek." I told her I had a DNA test, but she was not interested in that. Only the names of the biological father and mother would do. I asked how orphans were supposed to come up with that information when they had been abandoned at an orphanage? Not her problem. What about the fact that apparently the Greek government had jurisdiction enough to sell me off for adoption and ship me overseas? Irrelevant. I finally asked her if that meant that Greek orphans in Greece had to apply for citizenship when they came of age, and at that point the conversation came to an end. She suggested that if I had a problem with it, I should get a Greek lawyer, in Greece, and pursue it. So there you go. The ultimate Catch-22 for orphans, and how appropriate for the @#$^&! age we live in.

So, after that, I thought, what the hell, I'll do Ancestry.com's DNA test because they match you up with genetic relatives as well as the general heritage. First off, they disagreed with National Geographic: according to them, I'm 85% Greek/Balkan, and only 13% Italian. The rest is kind of vague... But here's the kicker. I went to the list of DNA matches... and I have none. The closest I get is a short list of people who might be my 4th to 6th cousins. What this means - looking at the chart below - is that while we might have crossed paths at an airport, no living relatives have shared bread, wine, or talk for probably 100 years.

My first reaction was that I was like a fox, looking for a hole in a fox hunt, and all the earths are stopped.

My second, was that I was back on that effing wedge of rock.

My third was that the universe was being very clear, and while I didn't like it, I was going to have to accept it.

And then, as Mr. Edwards said to Dr. Johnson, "Cheerfulness breaks in."

I called a dear friend of mine and told her the latest, and she said, "Oh my God! You really are an alien! You really are from some other planet!" And we laughed our heads off.

So, now I have decided to embrace the truth: Sometime after the Neanderthal/ Denisovian encounter, or at the latest after the little trip to the Kashmiri serai, my gene pool carriers took off somewhere else. And then - after some trouble in that particular space-time continuum - dropped me off at the Athens Municipal Foundling Home. Or so they say...

Will keep you posted. Oh, and if anyone out there knows who the little girl below used to be, please let me know.

Labels:

adoption,

black market,

Eve Fisher,

Greece,

Neanderthal

19 June 2019

It's So Crazy It Might Just... Be Crazy

|

| The author (R) with lampshade. |

At one point a character said: "That is absurd."

And my reaction was: "Wow. Nice piece of lampshade-hanging."

I discussed this concept in passing once before. It refers to a method of coping with a particular authorial dilemma.

Let's say your story involves a plot twist or coincidence so outlandish you are afraid the readers will roll their eyes and throw the book across the room. That happens. If you can't change the plot, how can you change the reader's reaction to it?

Well, one method is to "hang a lampshade on it." This means that, instead of trying to draw attention away from the problem, you actually have a character point it out. This seems counter-intuitive, but it often works. Maybe you are indicating to the readers that you know how smart they are.

As the wonderful web site TV Tropes points out, the ol' Bard of Avon could hang a lampshade as neatly as any pulp magazine hack: Fabian: If this were play'd upon a stage now, I could condemn it as an improbable fiction. (Twelfth Night)

A related method is known as So Crazy It Just Might Work. Do I have to explain what that means? You've read it/seen it in a thousand action movies. It is practically Captain James Kirk's middle name.*

But I would suggest you can divide SCIJMW into two types: Physics and People. One is better than the other, I think.

Physics: "There's no way the ship's engines can pull us out of the Interplanetary Squid Forest, so let's go full speed ahead straight in! It's so crazy etc."

People: "They have hundreds of armed guards hunting for us everywhere. The one thing they'll never expect us to do is walk up to the prison and sign in as visitors. It's so crazy etc."

Both are crazy (although not as crazy as an Interplanetary Squid Forest) but the second one seems more reasonable to me because it is based on reverse psychology. And hey, that sometimes works in real life. Remember the event that was the basis for the movie Argo? Who would expect the CIA to sneak people out of the country by setting them up as a film crew?

SPOILERS AHEAD.

Another way of grappling with an improbable plot point is foreshadowing. I think it was Lawrence Block who pointed out my favorite example of that technique. In The Dead Zone Stephen King has a lightning rod salesman show up at a bar and try to convince the owner to buy, pointing out the building's location makes it a perfect target for boom. The owner turns him down and the salesman drives off, his service to literature complete. When lightning strikes the bar at the very moment the plot requires it the reader, instead of saying "How unlikely!", says "Ha! The salesman was right!"

Of course, foreshadowing can be used for different purposes.

In the brilliant TV series I, Claudius there is a scene where a seer witnesses what appears to be an omen. He interprets it to mean that young Claudius will grow up to be the rescuer of Rome. Claudius's sister Livilla scornfully says that she hopes she will be dead before that happens. Their mother says "Wicked girl! Go to bed without your supper." Guess when and how Livilla dies?

So if you are a writer how do you deal with an attacks of the Unlikelies? And if you are a reader (and I know you all are) which types bother you the most?

* Yes, I know Captain Kirk's middle name is Tiberius. Now go over there and sit down.

Labels:

Blacklist,

Claudius,

foreshadowing,