Poor Aristotle. According

to Dorothy L Sayers, he was born at the wrong time, forced to make do

with the likes of Sophocles and Euripides while truly craving, as she

puts it, "a Good Detective Story." In "Aristotle on Detective Fiction," a

1935 Oxford lecture, Sayers takes a look at the philosopher's

definition of tragedy in the

Poetics and decides it fits the modern detective story nicely. If Aristotle had been able to get a copy of

Trent's Last Case, maybe he would have skipped all those performances of

Oedipus Tyrannus and

The Trojan Women.

It

doesn't do, of course, to challenge Dorothy Sayers on the nature of the

detective story. But her lecture seems more than a little tongue in

cheek, and her attempt to equate the detective story with tragedy falls

short. At its heart, the detective story is more comic than tragic. And

I'm willing to bet Sayers knew it.

She begins her

lecture by identifying similarities between detective stories and

tragedies. Aristotle says action is primary in tragedies, and that's

true of detective stories, too. Keeping a straight face, not

acknowledging she's made a tiny change in the original, Sayers quotes

the

Poetics: "The first essential, the life and soul, so to

speak, of the detective story, is the Plot." Aristotle says tragic plots

must center on "serious" actions. That's another easy matchup, for

"murder," as Sayers observes, "is an action of a tolerably serious

nature." According to Aristotle, the action of a tragedy must be

"complete in itself," it must avoid the improbable and the coincidental,

and its "necessary parts" consist of Reversal of Fortune, Discovery,

and Suffering. Sayers has no trouble proving good detective stories

adhere to all these principles.

When

she comes to Aristotle's discussion of Character, however, Sayers has

to stretch things a bit. Referring to perhaps the most familiar passage

in the

Poetics, Sayers cites Aristotle's contention that the

central figure in a tragedy should be, as she puts it, "an intermediate

kind of person--a decent man with a bad kink in him." Writers of

detective stories, Sayers says, agree: "For the more the villain

resembles an ordinary man, the more shall we feel pity and horror at his

crime and the greater will be our surprise at his detection."

True

enough. The problem is that when Aristotle calls for a character

brought low not by "vice or depravity" but by "some error or frailty,"

he's not describing the villain. To use phrases most of us probably

learned in high school, he's describing the "tragic hero" who has a

"tragic flaw." So the hero of a tragedy is like the villain of a

mystery--hardly proof that tragedy and mystery are essentially the same.

This

discrepancy points to the central problem with Sayers's argument, a

problem of which she was undoubtedly aware. The principal Reversal of

Fortune in a tragedy is from prosperity to adversity--but that's just

the first half of a detective story. To find a complete model for the

plot of the detective story, we must look not to tragedy but to comedy.

(Please note, by the way, that Sayers was talking specifically about

detective stories, not about mysteries in general. So am I. Thrillers,

noir stories, and other varieties of mysteries may not be comic in the

least--including some literary mysteries that borrow a few elements of

the detective story but really focus on proving life is wretched and

pointless, not on solving a crime.)

Unfortunately,

Aristotle doesn't provide a full definition of comedy. Scholars say he

did write a treatise on comedy, but it was lost over the centuries. The

everyday definition of comedy as "something funny" won't cut it. The

Divine Comedy

isn't a lot of laughs, but who would dare to say Dante mistitled his

masterpiece? Turning again to high-school formulas, we can say the

essential characteristic of comedy is the happy ending. As the standard

shorthand definition has it, tragedies end with funerals, comedies with

weddings.

For a more extended definition of comedy, we can look to Northrup Frye's now-classic

Anatomy of Criticism

(1957). Comedy, Frye says, typically has a three-part structure: It

begins with order, dissolves into disorder, and ends with order

restored, often at a higher level. Simultaneously, comedy moves "from

illusion to reality." Using a comparison that seems especially apt for

detective stories, Frye says the action in comedy "is not unlike the

action of a lawsuit, in which plaintiff and defendant construct

different versions of the same situation, one finally being judged as

real and the other as illusory." Along the way, complications arise, but

they get resolved through "scenes of discovery and reconciliation."

Often, toward the end, comedies include what Frye terms a "point of

ritual death," a moment when the protagonist faces terrible danger. But

then, "by a twist in the plot," the comic spirit triumphs. Following a

"ritual of expulsion which gets rid of some irreconcilable character,"

things get better for everyone else.

How well does the

detective story fit this comic pattern? Pretty darn well. (Frye himself

mentions "the amateur detective of modern fiction" as one variation of a

classic comic character.) The detective story usually starts with

order, or apparent order--the deceptively harmonious English village,

the superficially happy family, the workplace where everyone seems to

get along. Then a crime--usually murder--plunges everything into

disorder. Complications ensue, conflicts escalate, the wrong people get

suspected, dangers threaten to engulf the innocent, the guilty evade

punishment, and illusion eclipses reality. But the detective starts to

set things right during "scenes of discovery and reconciliation." Often

after surviving a "point of ritual death" (which he or she may shrug off

as a "close call"), the detective identifies the guilty and clears the

innocent. The villain is rendered powerless through a "ritual of

expulsion"--arrest, violent death, suicide, or, sometimes, escape. Order

is restored, and a happy ending is achieved "by a twist in the plot."

To find a specific example, we can turn to Sayers's own detective stories.

Gaudy Night

makes an especially tempting choice. In the opening chapters, order

prevails at quiet Shrewsbury College, and also in the lives of Lord

Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane. He proposes at set intervals, and she

finds tactful ways to say no. The serenity on campus, however, is more

apparent than real. Beneath the surface, tensions and secrets churn.

Then

a series of mysterious events shatters the tranquility, and Harriet and

Lord Peter get drawn into the chaos. Incidents become increasingly

frightening, tensions soar as suspicion shifts from don to don and from

student to student, and truth seems hopelessly elusive. Harriet

undergoes a "point of ritual death" when she encounters the malefactor

in a dark passageway. But "scenes of discovery and reconciliation"

follow as Lord Peter unveils the truth, as relationships strained by

suspicion heal. Illusions are dispelled, realities recognized. A "ritual

of expulsion"--a gentle one this time--removes the person who caused

the disorder. And, in the true, full spirit of comedy, the detective

story ends with order restored at a higher level, with the promise of a

wedding.

How

many detective stories end with weddings, or with promises of weddings,

as lovers kept apart by danger and suspicion unite in the final

chapter? A number of Agatha Christie's works come to mind, along with

legions of recent ones that bring together a police officer (usually

male) and an amateur sleuth (usually female). Of course, if the author

is writing a series and wants to stretch out the sexual tension, the

wedding may be delayed--Sayers herself pioneered this technique. Still,

the wedding beckons from novel to novel, enticing us with the prospect

of an even happier ending after a dozen or so murders have been solved.

Romance isn't a necessary element, either in comedies or in detective

stories. But it crops up frequently, for it's compatible with the

fundamentally optimistic spirit of both.

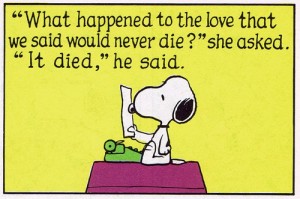

Humor, too, is

compatible with an optimistic spirit, and it's nearly as common in

detective stories as in comedies, from Sherlock Holmes's droll asides

straight through to Stephanie Plum's one-liners. To some, it may seem

tasteless to crack jokes while there's a corpse in the room. On the

whole, though, humor seems consistent with the tough-minded attitude of

both comedies and detective stories. Neither hides from life's

problems--there could be no story without them--but neither responds

with weeping or wringing hands. In both genres, protagonists respond to

problems by looking for solutions, sustained by their conviction that

problems can in fact be solved. The humor reminds both protagonists and

readers that, even in the wake of deaths and other disasters, life isn't

utterly bleak. Things can still turn out well.

Some

might say the comparison with comedy works only if we stick to what is

sometimes called the traditional detective story. Yes, Dupin restores

order and preserves the reputation of an exalted personage by finding

the purloined letter, and Holmes saves an innocent bride-to-be by

solving the mystery of the speckled band. But what of darker detective

stories? If we stray too far from the English countryside and venture

down the mean streets of the hard-boiled P.I. or big-city cop, what

traces of comedy will we find? We'll find wisecracks, sure--but they'll

be bitter wisecracks, reflecting the world-weary attitudes of the

protagonists. In these stories, little order seems to exist in the first

place. So how can it be restored? How can an optimistic view of life be

affirmed?

The Maltese Falcon looks like a

detective story that could hardly be less comic. The mysterious black

figurine turns out to be a fake, Sam Spade hands the woman he might love

over to the police, and he doesn't even get to keep the lousy thousand

bucks he's extracted as his fee. It's not a jolly way to end.

Even

so, in some sense, order is restored. Spade has uncovered the truth.

He's made sure the innocent remain free and the guilty get punished. He

has acted. As he says, "When a man's partner is killed he's supposed to

do something about it." Spade has done something.

Maybe,

ultimately, that's the defining characteristic of comedy, and of the

detective story. Protagonists do something, and endings are happier as a

result--maybe not blissfully happy, but more just, more truthful,

better. In detective stories, and in comedies, protagonists don't feel

so overwhelmed by the unfairness of the universe that they sink into

passivity and despair.

Maybe that's the real thesis of

"Aristotle on Detective Fiction." In some ways, Sayers's playful

comparison of tragedies and detective stories seems unconvincing.

Probably, though, her real purpose isn't to argue that the detective

story is tragedy rather than comedy. Probably, her purpose is to enlist

Aristotle as an ally against what she describes as "that school of

thought for which the best kind of play or story is that in which

nothing particular happens from beginning to end." That school of

thought remains powerful today, praising literary fiction in which

helpless, hopeless characters meander morosely through a miserable,

meaningless morass, unable to act decisively. Sayers takes a stand for

action, for saying the things human beings do make a difference, for

saying we are not just victims. Both comedy and the detective story

could not agree more.