To My Comrades in Nicaragua

I dedicate this effort to do justice to their acts and motives: To the living, with the hope that we may soon meet again on the soil for which we have suffered more than the pangs of death– the reproaches of a people for whose welfare we stood ready to die: To the memory of those who perished in the struggle, with the vow that as long as life lasts no peace shall remain with the foes who libel their names and strive to tear away the laurel which hangs over their graves.

– William Walker, prefatory dedication for The War in Nicaragua (1860)

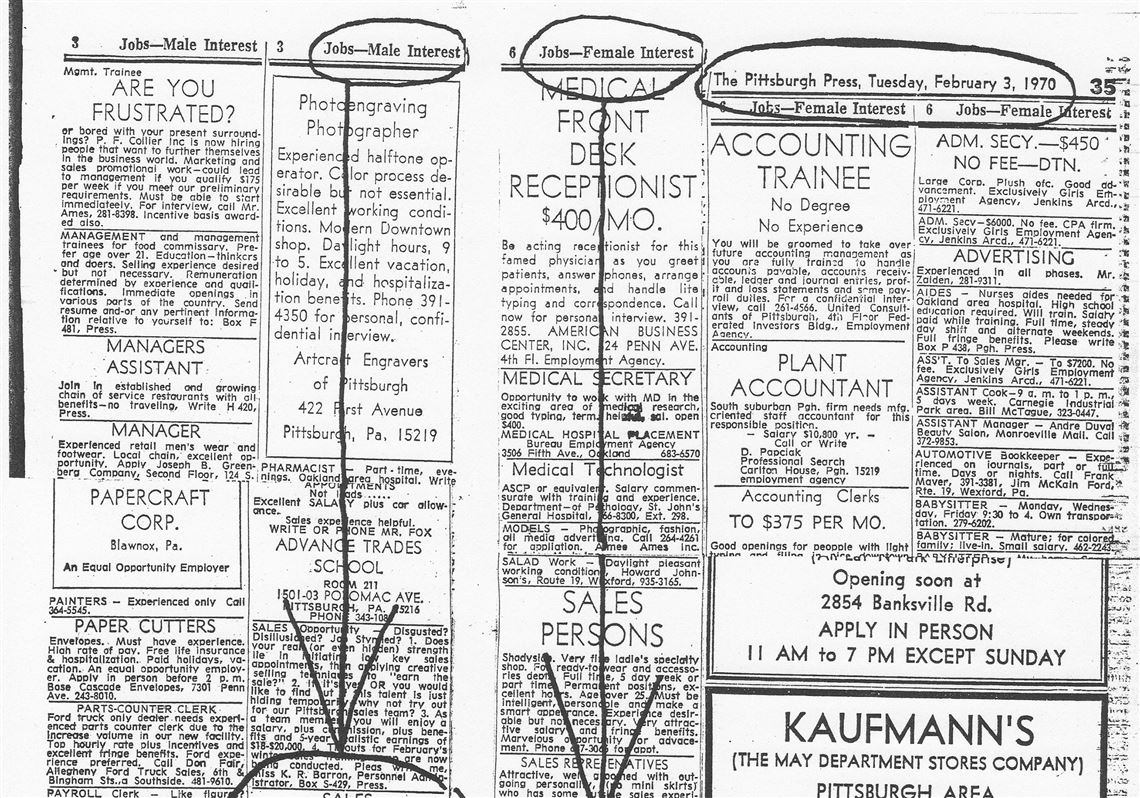

|

| So, not THIS type of filibuster... |

filibuster - Informal term for any attempt to block or delay Senate action on a bill or other matter by debating it at length, by offering numerous procedural motions, or by any other delaying or obstructive actions.

The term "filibuster," as defined above, is likely to evoke passionate responses both

for and

against its existence and frequent use in legislative bodies such as the U.S. Senate. And this is an election year, and we are less than six months from Election Day 2020,. And while it might be both timely and informative to discuss this Senate rule which has been around since 1806, and yes, we are definitely going to talk about "filibusters" as today's topic.

We're just not going to talk about a political maneuver which uses words as weapons.

|

| THIS type. |

Instead we're going to talk about the kind of filibusters which use

actual weapons as weapons. So, "military filibusters." Why the confusing use of the same word to mean vastly different things?

Well.

The word itself comes to English by way of both French ("

filibustier") and Spanish ("

filibustero") words derived from the Dutch

vrijbuiter, which means "robber," "thief," or "pirate," and which has also directly entered the English language as "freebooter."

In each of these iterations there is a strong subtext that attaches notions of subterfuge, even sabotage, to the word. This presumption underlies our best guess as to how the word "filibuster" managed to also morph into a political term: a "filibuster" is literally used in an attempt to sabotage the potential passage of a piece of legislation which appears about to be voted into law.

But about those other filibusters. Imagine looking out your window, and seeing dozens of armed, men in paramilitary gear, almost never bearing any official insignia, armed to the teeth, and clearly wanting something and willing to at least

show force in order to get it.

Oh, and they're almost

always American citizens.

If it's 2020, and you live across the street from, say, the Michigan state capitol, those are citizens exercising their constitutional right to assemble and protest against something their governor is doing (or, maybe not doing?). They have every right to do this, no matter how scary or lawless it looks (which, I think, is usually the point of "packing" when showing up to a protest. I wouldn't actually know, because every time I've attended a protest, I've been unarmed.).

If, however, it's the 1840s or 1850s, or even later, throughout much of the second half of the 19th century (with four years off for the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865), and you're

somewhere abutting the Caribbean Basin, whether it be Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, or any of a number of the smaller Central American republics that had recently won their freedom from Spain and you suddenly find a bunch of armed

Norteamericanos on your doorstep, your neighborhood is likely on the receiving end of

this type of "filibuster."

The vast majority of these expeditions were launched with a single intent: conquest. Granted, if the guys doing the actual filibustering, to say nothing of the money men back in the good old U.S. of A., managed to enrich themselves at the expense of the peoples they were bent on conquering (usually in advance of some hazy, poorly thought-out and never-executed plan to petition the United States for admission,

a la Texas), well then, so much the better.

|

| Aaron Burr – Original Filibuster? |

In fact the first American filibusters followed the example of Aaron Burr, the brilliant, erratic former vice-president of the United States. Burr, whose career began with such promise, eventually left office in disgrace (after killing his long-time rival Alexander Hamilton in a duel), only to reappear on the national stage late in life, and attempt to swipe a big chunk of what is now the American South and inland Midwest. His apparent intention: setting himself up as some sort of potentate there. Since there is no "Empire of Burrlandia" to found anywhere within the continental United States, you can guess how

that went. (Fun fact: the Senate procedural rule that eventually came to be known as a "filibuster" was created in 1806, by the Senate's presiding officer. Can you guess who that was? Yep: then-Vice-President Aaron Burr.).

And in truth the practice pretty much started

with Texas. As early as 1810, when a Mexican priest started a revolt against Spain, colorful characters came out of the woodwork to invade Texas. Men such as Augustus Magee–a distinguished West Point graduate who resigned his commission in the U.S. Army to raise and lead a band of American ex-soldier "volunteers" into Texas in ostensible support of the Mexican Revolution, only to die of one of the following: either consumption, malaria, or possibly even poisoning by his own troops. And then there was Virginia-born James Long. In 1819, Long raised and led a group of armed Americans into Texas, seized Nacogdoches, declared the establishment of a "Republic of Texas," and had himself made president.

He met

his end in a Mexican prison three years later, shot by a prison guard under mysterious circumstances.

But it wasn't just Texas. Wave after wave of armed civilians left ports in the southern United States (usually, but not always, New Orleans) for places with Spanish names and "emerging" governments. Countries (with the exception of Cuba, which remained a Spanish colony until 1898 when the United States military helped liberate the island.) newly freed of Spain's colonial yoke, without an established tradition of self-government, and vulnerable to the predations of small groups of armed men, bent on looting, and, if possible, conquest.

None of these "unofficial" military actions was sanctioned by the United States government. Which is not to say that "filibusters" were unpopular with Americans. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Portrayed by many American newspapers as intrepid adventurers interested in safeguarding the vulnerable, while also potentially expanding the territory of the United States at the expense of "foreigners," filibusters succeeded in capturing the imagination of a mostly admiring American public.

|

| James K. Polk – Official Filibuster? |

This is unsurprising in light of the overwhelming success of what might be termed a "sanctioned" filibustering expedition: the annexation of Texas and the subsequent invasion of Mexico by U.S. troops, including some pretty irregular "militia," during the mid-to-late 1840s. The diplomatic conflict over territorial claims to Texas, and the war that quickly followed on its heels, was engineered (some would say "masterminded") by Tennessean James K. Polk. Polk ran for president making territorial expansion of the United States his central campaign promise. And when he ascended to the presidency, he more than made good on that promise.

While it's true that the so-called "Mexican War" (hint: that's

NOT what they call it in Mexico) was extremely popular in certain parts of the United States, there was widespread opposition to it in other sections of the country . These states (especially in the industrial Northeast) opposed the territorial expansion of the nation through the addition of slave territory, and most of the new territory was delegated as slave territory, especially Texas, where it was already widely practiced.

All of the millions of acres of new land acquired by the successful conclusion of the MexicanWar did nothing to sate the taste for filibustering in the American South. If anything the 1850s proved to be the high point of the practice, with expeditions organized and mounted under the leadership of Mexican War veterans such as former Mississippi governor (and late general of volunteers) John Quitman, whose well-financed proposed expedition to "liberate" Cuba and add her to the Union as a new slave state was called off at the last minute under sudden and surprising pressure from the federal government, So Quitman ran for Congress instead. And won. He served until his death in 1858, and chaired the House Committee on Military Affairs.

But if the 1850s were the high tide of the practice of filibustering, the decade also witnessed the rise of the greatest and most successful of these filibusters: the man quoted at the beginning of this post, another "brilliant and erratic" American, William Walker of Tennessee.

Born in Nashville in 1824 and trained in Philadelphia as a physician (if he ever practiced, there's no record of it), Walker seems to have been preternaturally restless. Roaming throughout Europe for two years before catching gold fever and making his way to California in 1849, Walker was living in Sacramento when he first hit upon the notion of turning his hand to filibustering.

In 1853 he sailed from San Francisco one step ahead of the U.S. Army (They wanted to arrest him for plotting to violate the Neutrality Act–a crime of which he was

clearly guilty.) with less than fifty followers. He soon landed in what is now Baja California, where he stole provisions from the locals, seized the state capitol city of La Paz and set up a "Republic of Lower California." Then Walker tried (and failed) to annex the neighboring state of Sonora, saw his "republic" collapse, and crossed the border at San Diego, where he surrendered to the army garrison there one step ahead of some of the Mexican landholders he'd robbed upon first arriving in the region two months previously.

As it turned out, this was little more than a dress rehearsal. In 1854 Walker was tried in California on a charge of violating the Neutrality Act. Public opinion was so completely behind him that it took the jury less than ten minutes to acquit him.

Walker benefitted from some very good press back home in the United States, especially in the South. This was in part because one of his first official acts as "president" of his spurious and never-recognized "republic" in Baja was the legalization of slavery. This action endeared him to Southerners still convinced that the best way to preserve the institution of slavery was through its extension throughout out the continent. With abolitionist opposition to the institution on the rise, the sections drawing up sides for a brewing civil war, Walker found himself a folk hero, dubbed the "Grey-Eyed Man of Destiny" by a fawning press.

All of this good PR led to hundreds of would-be filibusters seeking out Walker in California as he immediately began preparing for another expedition south. In 1855 he once again set sail from San Francisco, this time bound for Nicaragua.

|

| Walker's next stop. |

|

| Henningsen the Butcher |

Initially allying himself with the country's liberals, Walker took advantage of the country's political instability and played several of the factions there off against each other. Within a year he'd gotten himself "elected" president.

Having achieved power, Walker proved ruthless in his attempts to keep it. Alongside pointless show legislation intended to be popular back in the United States (One such piece of legislation changed Nicaragua's official language from Spanish to English,) he also immediately legalized slavery, and set about putting down dissent within the country by turning his troops on the populace. In one particularly horrifying instance Walker sent a detachment of his followers under one of his officers, the English-born Charles Frederick Henningsen, to put down unrest in the city of Granada. Henningsen's men killed many of the residents, burned the city and then retreated with several thousand Honduran soldiers in hot pursuit. He left behind a sign marking the smoking ruin of the city with the phrase “

Aquí fue Granada” (“Here was Granada”).

|

| The "Commodore" |

By 1857 Walker had worn out his welcome. Not only had he made thousands of local enemies, he had also incurred the enmity one of the richest men in the world: American millionaire “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt. Vanderbilt's company did a brisk trade running people and cargo via a network of rail lines and lake steamers from the Gulf of Mexico, across the huge Lake Nicaragua, and downslope to steamboats waiting in Corrinto on Nicaragua's Pacific coast, to take travelers the rest of the way to California.

When Walker nationalized Vanderbilt’s lake steamers, the “Commodore” set a collection of well-financed, professional "problem-solvers" the task of ousting Walker and securing the return Vanderbilt’s property. In face of such resources of men, money and weapons as Vanderbilt could muster, Walker's "government" collapsed virtually overnight. Once again one step ahead of his pursuers, Walker surrendered to the captain of an American warship, returned to a hero’s welcome in New York, and wrote a book (quoted above) about his exploits. Within a year he had hatched a scheme to return to power in Nicaragua.

This time Walker’s luck had run out. He landed in Honduras in 1860, and instantly found himself in the custody of the British navy. Rather than return Walker to the US, the British—who controlled Honduras’ neighbor British Honduras, now Belize—turned him over to the Honduran government as a gesture of good will. A firing squad executed Walker on the site of what is now a hospital in the port city of Trujillo, on September 12, 1860. He was just thirty-six years old, and missed the American Civil War by a mere three months.

The Civil War hardly ended American incursions into the long-suffering countries of Latin America and the Caribbean Basin, though. If anything it intensified them and made them more official. By ending the age of filibusters, and running the French out of Mexico after the cessation of hostilities in the War Between the States, the U.S. government took the first steps toward Great Power status, and that included moving to limit the activities of European world powers in the Western Hemisphere.

So the

Norteamericanos continued to invade countries such as Mexico, Nicaragua, Cuba, and others for decades after the end of the Civil War. But they were no longer privately-organized irregular troops. They were usually United States Marines. And their presence in the interest of "securing American lives and property in the region" usually included propping up a succession of tin-pot local strongmen and their descendants, such as the Somozas in Nicaragua. The Sandinista rebels who overthrew this regime after decades of despotic rule, did so in spite of continued U.S. government assistance even after the Somozas were out of power.

And that's how things like "Iran-Contra" happened.

|

| United States Marines posing with a captured rebel flag in Nicaragua, 1932 |

Followers of this blog (

BOTH of you!

*rimshot*) may see how this post ties in with my most recent previous one written a couple of weeks back and dealing with the

white supremacist underpinnings of the wave of Confederate memorial monuments erected from the 1890s through the 1930s as a way to remind African Americans of their "place" in American society. I say the following as a patriot who loves his country, who does his best to see the ugly truths contained within the American experience while also not forgetting the positive, aspirational nature embedded at the core of our shared national identity. To be an American is to be a practitioner of hope.

But if we are going to move forward as a people from the moment in which we now find ourselves, we, as a people, must be willing to cast an unblinking gaze upon our stained legacy. Only then can we do better.

After all, as History shows us, we have already done worse.