Sixteen years later, we've seen many rise and fall. The Big Click, an online with subscriptions edited by Nick Mamatas. ThugLit, edited by Todd Robinson, which had many stories chosen for The Best American Mystery Stories, and my Jay Desmarteaux yarn "The Last Detail." Spinetingler, an online magazine that had a brief Kindle edition (my story "Two to Tango" appears in it) and they have announced a print edition. All Due Respect, which was online, and now gone, published "White People Problems," which later became "Mannish Water," published in Betty Fedora, which is still around, publishing irregularly. A newcomer is Down & Out Magazine, by the press of the same name (my publisher) which has published two print issues. Another is Black Cat Mystery Magazine, from Wildside Press, which just published its first issue.

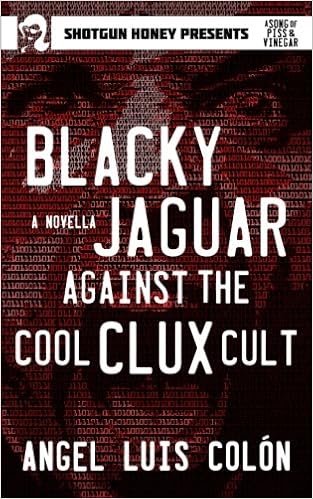

There are many more that have come and gone. Needle, a Magazine of Noir. Shotgun Honey, the forefront of flash fiction, remains publishing. Powder Burn Flash, Hardboiled Magazine, started in 1985 by Wayne D. Dundee and taken over by Gary Lovisi, a print-only pulp, shuttered a year or so ago. Murdaland (RIP), Manslaughter Review (alive, a yearly publication), Plots With Guns (I can't tell, they're like the killer in a slasher movie, never count them out), The Flash Fiction Offensive, Out of the Gutter, Dark City. There's also The Strand and Suspense Magazine in print, but I've never gotten a response from either editor for stories or interview queries. I know The Strand publishes one new story a month, so they're a tough one to break into, but you'll be among the legends if you do.

One mag that came up, in bitter memory, was the short-lived NOIR Magazine that raised $36,000 by crowdfunding for a digital-only release on iPad. I was a contributor. With such a limited market, iPad owners, I didn't understand how they would last. I read it on my mom's iPad. It was buggy and I couldn't read it. And then NOIR Magazine was gone. I hope the authors were paid well, because that was a big chunk of change for one issue. Gamut Magazine was multigenre and raised $55,000 - Editor Richard Thomas just announced they're shuttering after a SINGLE YEAR. After a 30% increase in subscriptions. I'm not sure they had a sustainable business model if a 30% jump in subs wasn't enough to keep it afloat. It's rough out there. If you read on, you'll see that getting $2.99 an issue for a magazine that produced regular award-winners can be like pulling teeth.

What's the deal?

Another thing that hasn't changed is that some pay pro or semi-pro rates, others don't pay at all, and a few pay the Mystery Writers of America minimum of $25, which lets them be anointed as official markets and be considered for the Edgars. If you write a 2500 word story, that's a penny a word. Considered pulp rate in the '30s, maybe you can buy lunch with it these days. No offense to the magazines who pay this rate, but I wish the MWA looked toward the SFWA and set a higher bar for professional rates. It would shrink the pool of "official markets," yes. But wouldn't it be nice to be paid a nickel a word? But to do that, you have to sell copies. And fewer and fewer are sold these days. I couldn't find Alfred Hitchcock or Ellery Queen at Barnes & Noble. You can get them at The Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, or you can subscribe.

So I wanted to get an idea of what could be done to enrich the short story market for crime fiction, so I asked six editors a few questions about the state of things. My questions in bold.

Carla Coupe, Black Cat Mystery Magazine (in print and accepting submissions)

Carla Coupe has been at Wildside Press for over 7 years, and co-edits Black Cat Mystery Magazine, their newest publication. Her short stories have appeared in several anthologies, and two were nominated for Agatha Awards. One of her Sherlock Holmes pastiches, "The Book of Tobit," was included in The Best American Mystery Stories of 2012. (Read her full interview with Barb Goffman here.)

Why do you think a market should pay, and does the MWA minimum have a bearing on your payment structure?

Markets should pay because writers are talented artists who deserve payment for their works. We pay a competitive per word rate, so the total amount depends on story length.

How much do you charge for an issue, and did raising or lowering the price have a severe impact on readership?

Paper copies are $10 each, plus shipping (but if you subscribe you get a price break), and the e-versions are $3.99 each (ditto regarding subscriptions). We want to keep both versions affordable and set our prices with that in mind.

Do you think the free online magazines cut into sales?

They probably do to some degree, but just as important is that they set the expectation that everything on the web should be free. It's very frustrating for many artists, authors, and musicians.

Does paying for a story raise the bar of quality of what you'll accept?

We've been very fortunate to receive many amazing stories--more than we can include in the next two issues--so that isn't an issue for us.

What has been your experience running a magazine in the crime genre, and why do you think there are fewer paying markets in Mystery than SF and Horror?

Since we have just started Black Cat Mystery Magazine, we don't have a lot of experiences to share yet. So far it's been very positive, if a bit hectic. We're fortunate that we have such a large pool of talented writers to draw from, and time will tell regarding our success in the marketplace. I'm not sure why there are fewer paying markets in the mystery and crime field -- perhaps because there are so many crime shows on TV? It could be that fans of the genre can get their mystery fix on the box, and/or don't have the time or inclination for reading. But that's just a guess.

Nick Mamatas, The Big Click (defunct, but back issues are online)

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including The Last Weekend, I Am Providence, and Hexen Sabbath. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories, Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy, Tor.com, and many other venues. Nick has also co-edited several anthologies, including Haunted Legends with Ellen Datlow, The Future is Japanese, Phantasm Japan, and Hanzai Japan with Masumi Washington, and Mixed Up with Molly Tanzer. His fiction and editorial work has variously been nominated for the Hugo, World Fantasy, Bram Stoker, Locus, and International Horror Guild awards.Why do you think markets should pay, and does the MWA minimum have a bearing on your payment structure?

I think MWA's minimum is too low. It should be higher. A minimum of $100 per story is essential.

How much did you charge for an issue, and do you think raising or lowering the price would have a severe impact on readership?

We were a free online magazine that sold advertising, and also sold ebook editions of our issues for $2.99 each. We also offered subscriptions via Weightless Books. Once upon a time, Amazon allowed for direct subscriptions via Kindle, but small magazines with no print component are no longer allowed in that program. The ones you can subscribe to are grandfathered in.

Do you think the free online magazines cut into sales?

No, it's a different model. Does radio cut in to live music ticket sales? Maybe in some abstract sense, but they're really just two different ways of making money from songs.

Does paying for a story raises the bar of quality of what you'll accept?

No, it raises the ceiling on the quality of story we received though.

What has been your experience running a magazine in the crime genre, and why do you think there are fewer paying markets in Mystery than SF and Horror?

The sense I got was that the novel is so important to the genre that short fiction was always ever a sideline. One thing we categorically refused to take was the "enhancement" story about some side adventure of a novelist's series character, which agents often encourage their writers to produce. We didn't want afterthoughts. We were offered many many afterthoughts.

I think SF and horror have more paying markets because of organized fandom in those genres—it's generally fans with a little money to burn who start magazines these days, and they do it because of their love of the genre and to become prominent in the "scene." The various awards in SF and horror have multiple short fiction categories, which also encourages writers to participate more. Crime/mystery doesn't have nearly the same level of organized fan activity.

Jack Getze, Spinetingler Magazine (in print and accepting submissions)

Former newsman Jack Getze is Fiction Editor for Anthony-nominated Spinetingler Magazine, one of the internet's oldest websites for noir, crime and horror short stories. His screwball mysteries -- BIG NUMBERS, BIG MONEY, BIG MOJO, and BIG SHOES -- were published by Down and Out Books, as is his new thriller, THE BLACK KACHINA. His short stories have appeared online at A Twist of Noir, Beat to a Pulp, The Big Adios, and several anthologies.

Why do you think a market should pay, and does the MWA minimum have a bearing on your payment structure?

We like to think everything we do is for the newer writers, including the small payment of $25. Getting paid for fiction meant a lot to Sandra and I when we started, and I think writers appreciate the token payment today as well. We'd like to raise that number if future sales allow it. The MWA minimum has not been a factor.

How much do you charge for an issue, and did raising or lowering the price have a severe impact on readership?

We've been online only, and thus free, for almost a decade, but we've just re-launched our print magazine in November. We're charging $5.95 for the ebook and $10.95 for the printed copy. Down & Out Books, our contract publisher, had considerable input on pricing. It could change in the future. Can't answer the second part because we haven't had enough time to gauge readership.

Do you think the free online magazines cut into sales?

No, personally I don't. I don't think readers buy a ton of short stories unless they're already interested in the writer. I might be wrong. Many people think it's the format, that apps and shorter stories you can read quickly on the telephone might be a more salable product. That takes money and investment that Spinetingler doesn't have right now. When Sandra calls me Spinetingler's "owner," it's because I get to pay the bills.

Does paying for a story raises the bar of quality of what you'll accept?

No. We've paid since inception, and my criteria is pretty simple: I buy the stories I personally enjoy reading.

What has been your experience running a magazine in the crime genre, and why do you think there are fewer paying markets in Mystery than SF and Horror?

We run some horror at Spinetingler, although not as much as crime, suspense and mystery. I'd run more horror if I saw stories I liked because our readers enjoy the it, but many submissions seem too gory for me. I had to call a fairly well known writer once and apologize. The writing was so good, the story intriguing, but damn it was gory with lots of body parts and blood. I couldn't finish, told the man somebody else would buy. Not me.

I believe sci-fi and horror have captured young readers' hearts more than mystery. Not sure why, but my guess is the tired image of Sherlock Holmes dooms the genre to a sitting room where old people sit and drink tea. Solving crimes is not as much fun as running from zombies. Every young person I know personally -- anybody under 50 is young to me -- loves sci-fi, horror and speculative fiction. I hope mystery isn't on the way out but I worry whenever I attend a mystery conference. Not many young readers.

Eric Campbell and Rick Ollerman, Down & Out Magazine (in print and accepting submissions)

Eric Campbell is the founder and publisher of Down & Out Books. After spending twenty-five years in healthcare finance, Eric started Down & Out Books as an avenue to help develop and build “lost” authors. Since then, the company has published over 200 books and is home to several imprints including All Due Respect, Shotgun Honey and ABC Documentation. The company specializes in the crime, thriller and suspense genres.

Rick Ollerman was born in Minneapolis but moved to more humid pastures in Florida when he got out of school. He made his first dollar from writing when he sent a question into a crossword magazine as a very young boy. Later he went on to hold world records for various large skydives, has appeared in a photo spread in LIFE magazine, another in The National Enquirer, can be seen on an inspirational poster shown during the opening credits of a popular TV show, and has been interviewed on CNN. He was also an extra in the film Purple Rain where he had a full screen shot a little more than nine minutes in. His writing has appeared in technical and sporting magazines and he has edited, proofread, and written numerous introductions for many books. He’s never found a crossword magazine that pays more than that first dollar and in the meantime lives in northern New Hampshire with his wife, two children and two Golden Retrievers.

Eric: To get good stories from top name authors, yes, we need to pay. They've taken time to write the story and, while the payment is pretty small, I hope to see that grow over time. If we get the the big names then we should be able to submit to MWA for consideration. So yes, the minimum did come was discussed when Rick and I first talked about launching the magazine.

Rick: The MWA minimum has a huge bearing on payment. The minimum is not large but it does several things: it makes each story we buy a professional transaction for the writer, it makes their work eligible for awards consideration (which would be wonderful for circulation), and as Eric says later, free does not work as a business model in the book and magazine business. If we don’t respect your work enough to pay for it, how willing are you going to be to work with me on the editing—some of which gets extensive, I’m not just a pass/fail type editor (two stories in the new issues have endings from me, and a story in the next issue will as well. Why do that much work for free? It’s because we’re all bonded by the desire to make each of these stories the best they can be). I only wish we could start out paying a per word rate like the two biggies in the field.

Interestingly, most of the writers have been surprised they get paid at all, even though it’s clearly stated on our submissions web page. They just want a story in our magazine. Which is another recurring thing I heard at Bouchercon: I want a story in your magazine. When Eric and I first talked about this and he asked, what should we call it, I immediately said, “Down & Out: The Magazine. D&O Books already has the image and identity you want to put out there. It would be up to us to put out a magazine worthwhile enough to bear the name.” And there’s no doubt in my mind we’re doing it, even though we’re young. I can tell you as editor I am uncompromising as to the stories that I’ll buy. And the idea is to get magazine readers to discover a writer’s books—which a number of people have told has happened with your own—and vice versa. We’re hoping contributing authors will publicize the existence of their work in the magazine, too.

How much do you charge for an issue, and did raising or lowering the price have a severe impact on readership?

Eric: The cost of each issue is $11.99 for TP and $5.99 for EB for a number of reasons. First, the authors are names you know and have been paid for their efforts. Second, until readership reaches a reasonable number to justify a print run, the book is POD so the cost to publish is a little higher. Third, the stories have been professionally edited and proofread. Bottom line, Down & Out: The Magazine is a high quality product with well-written stories. While lowering the price may result in a few add'l purchases, I don't think it would be substantial.

Rick: If you made the book free, or two dollars, the consumer values it lower than they would a competitive magazine with inferior stories that carries a higher retail price. Free doesn’t work. Occasional free can work wonderfully, occasional cheap can give you a nice boost in the arm and build loyalty from your customers, but an all the time free or cheap project simply means that’s the place your product will occupy in the consumer’s mind—at the bottom.

Show me one of the new magazines that has an all-new Moe Prager story by Reed Farrel Coleman? Or one that has a new Sheriff Dan Rhodes story by Bill Crider? In the next issue it’s a new Jim Brodie story by Barry Lancet? It doesn’t happen anywhere else.

Other magazines have used public domain short stories to fill pages because they’re cheap but we actually curate the stories we reprint and pay the entity that currently owns Black Mask. The short essays I write to introduce those stories should give readers an interesting peek into how we got here from there, then they get to read a story that may use language a bit looser than we do today but they’ll see that, damn, they’re fun to read.

Do you think the free online magazines cut into sales?

Eric: Free hurts everything we do. At some point though, free isn't sustainable. If you don't pay for content, then what kind of content will be available to you, the reader? As a publisher, you pay for the cover, edits, proofreading, layout, etc. and if something is free, then how to you recoup your costs and, more importantly, pay the author for their hard work.

Rick: Free also robs the spirit and the heart out of what we do. What a sad state for poets who get paid with a contributor’s copy of the digest that took their poem. There’s no payment, token though it may be, the magazine doesn’t sell much, so it’s not like they’re looking at a hot growth curve, so they muddle along. No, what we do is exciting. And so very hard. Working with writers whose stories may almost work but not quite, or don’t have an adequate ending, or are too fat in the middle, or have a twist ending that you can guess from the first page—these are all problems we work on in the editing if despite these problems there’s an actual story there. By the time the issue’s almost done, all the stories have run together in my mind and they all start to read the same. Why do I do that? Because I am going to make this thing a success. And that’s something more than that weekly 8-pager they hand out at the grocery store on Fridays.

Does paying for a story raises the bar of quality of what you'll accept?

Eric: Absolutely, without a doubt.

Rick: It does, but more it’s the reputation of Down & Out, it’s the personal invitations I extend to writers (because face it, us writers don’t get a ton of love that way), and there’s a sense out there that this is going to be something and they want to be a part of it.

What has been your experience running a magazine in the crime genre, and why do you think there are fewer paying markets in Mystery than SF and Horror?

Eric: Thus far we've published two issues and we're still crawling. We're trying to get the word out and grow this into a sustainable venture. It takes a lot of hard work from numerous folks to pull it together. Each issues will consist of 7 or 8 stories so if we do 4 issues a year, you're really talking about putting out 2 anthologies a year. That's a TON of work. I think there are fewer paying markets because total readership is down due to the aforementioned free content. Again, I don't believe that's sustainable when no one is making a penny. As much as we love what we do, you've still gotta eat.

Rick: I have no idea of the number of paying vs. non-paying magazines among different genres. I do know that for a while I was buying all the new magazines because I wanted to support not only the magazines, but my friends who were writing stories for them. But I found what I think most people find—I don’t like most of the stories. I just don’t. Maybe the writing’s okay but the poor endings ruin the experience. Or the writing’s just plain weak, on more of a high school level. Or the ideas are non-original and we’ve seen this story innumerable times before. Whatever. But I’d read these things and when I’d finish I’d have this funny twisted up feeling in my brain, like I’d just read something nobody had any business asking me to put down money for. That what I’d just read had been inconsistent. Three mediocre stories and one bad one can give me a feeling as though I’ve thrown away an entire day.

Everything we’re doing here is all aimed at accomplishing one thing: No. Bad. Stories. Not everyone can like every story. I can see one in particular in this second issue that is a good story but it is dark. And it’s that way because sometimes you just write a dark story. The point is, it’s good, and even if you read it and say, “That’s too dark for me, honey turn on all the lights,” you’ve already read it, it’s over, and you know you read a good story. Although you might not read that one again.

Todd Robinson, ThugLit (defunct, though back issues are available at Amazon)

Todd Robinson created and ran THUGLIT magazine for over a decade. He's not shilling anything in this bio. Sure, he wrote a couple of novels, but let's save us both the embarrassment of having to pretend you give a flying fuck.Hi, Todd! That's Todd. Because like Conan, Cimmerian, he will not cry (or shill) I will shill for him. The Hard Bounce and Rough Trade are his Boo Malone mysteries, about a bouncer in Boston who runs an investigative agency called 4DC (as in Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap) with his buddy. Good reads, Have at 'em.

Why do you think a market should pay, and did the MWA minimum have a bearing on your payment structure?

A market should pay, because any artist should be paid for their work. Even when we were a free online mag, I paid the writers with a t-shirt. And this was when we generated NO income whatsoever. It cost me almost three-hundred dollars per issue to produce the mag.

And while I think the offer of exposure is utter bullshit, we did legitimately give the authors that. I would never claim that it was a reason to submit to us (if you can get paid, you sure as shit should do so), but over time, the proof was in the pudding with regards to how many of our authors moved up the ladder by getting pubbed by us as a starting point. We worked our asses off to make sure as many people saw the work as possible. And that's a pride I still carry with me today. Every time I see a book on a shelf that started with the author having been published in Thuglit, Bitterness takes a short coffee break and allows Pride to have a small "Fuck, yeah" moment.

MWA made no impact whatsoever on our pricing. I'm not a member. The organization and I aren't friends. Part of it is that they even HAVE a fucking minimum, as though the price paid for a story is an indication of quality. Check the bookshelves, Best American Mystery Stories, the Anthony Awards, The MacCavity Awards…fuck it, ALL the awards (except the Edgars) to see if we presented amazing work from truly talented writers. According to the MWA, those stories aren't worth shit because of monetary ratios.

How much did you charge for an issue, and did raising or lowering the price have a severe impact on readership?

I started with the lowest price point at $0.99, and our readership dropped ninety-six percent. Apparently, thirteen cents a story was too much to ask. Once we rocketed up to six percent of the original readership, I raised the price to $1.99 and raised the author pay. Our readership dropped another third, and kept dropping until we were almost operating in the red in order to maintain the pay rate, and I shaved a decade off my life stressing daily about why we got all the acclaim, all the "love" and no sales.

Do you think the free online magazines cut into sales?

Absolutely. But like I said, we were free for years. And some of those free e-zines offer great material from editors who truly care about presenting quality fiction. Some just operate as a Mutual Admiration Society for authors to self-publish their own writing along with the works of their friends in order to impress their knitting circles. Those are usually fly-by-night productions that don't last six months, or whenever the jackasses realize how much work goes into it.

I made a lot of enemies with rejections, and never published a friend for being a friend. You can ask any writer that I'm close with personally. If the story wasn't good enough, it didn't get in. Period. Don't give a fuck who you are—or more importantly, who the fuck you thought you were. To do so would be a disservice to the few loyal readers we had, and a disservice to the writers themselves by presenting what amounted to a piece that didn't represent their talents to the fullest of their abilities.

I've said it before—we live in a society that would rather go to a free turd buffet with the off-chance that there's a shrimp hiding under a mountain of shit, than pay two bucks for a curated meal from a restaurant that built a reputation for high quality. I thought that over the years, we'd built a status that would have earned both us and the writers that much.

HOO boy, was I wrong.

Did paying for a story raise the bar of quality of what you'll accept?

Not at all. It increased the number of submissions we received, but the over/under on how many stories were quality over those that didn't live up to our standard remained the same. Our bar was set high with issue one. It never lowered. I never accepted a story from a "name writer" because I thought it would increase sales at the expense of a story I though was better. Would that have made sense business-wise? Sure. Am I as smart as I sometimes like to think I am? Fuuuuuuuck no.

What has been your experience running a magazine in the crime genre, and why do you think there are fewer paying markets in Mystery than SF and Horror?

It sucked. It was exasperating as hell. When I put up a video stating that I was ending the magazine, the goddamn thing got 7000 views in ten days, along with the wailing and gnashing of teeth that always accompanies a mag when it goes down. Problem was, we didn't move 7000 units of the magazine during the two years prior. If everyone who watched the video was willing to pony up what amounted to a buck a month, they wouldn't be watching that video!

I think it was that realization at the end that pushed me from straight-up frustration in to outright bitterness. Writers love having a market, but don't support them while they're in operation. But they sure will bitch and moan when they're gone.

The markets are disappearing because nobody wants to pay for the magazines. Fewer and fewer people read. Even fewer want to pay for it. That's the beginning, the middle, and the end of the problem. Writers can't get paid from a magazine when nobody is buying the magazine. Even the writers themselves.

Chris Rhatigan, All Due Respect (defunct)

Chris Rhatigan is a freelance editor and the publisher of All Due Respect Books.

Why do you think a market should pay, and does the MWA minimum have a bearing on your payment structure?

I don't think there's any particular amount a market should pay. It's nice if the magazine can at least send a contributor's copy. If the magazine is just a website, then there's no way in hell it's making any money, so it's a bit unreasonable to expect payment. MWA had no bearing on our payment structure.

How much do you charge for an issue, and did raising or lowering the price have a severe impact on readership?

We charged $2.99. When we did promos at 99 cents, we would sell triple the number of copies. The problem is Amazon's payment structure--you make 66% at $2.99 and up, but 33% at 99 cents. Of course, the idea is that you "hook new readers" with the lower prices, but I'm not convinced that ever happened.

Do you think the free online magazines cut into sales?

No. I've never perceived the short fiction market as a zero-sum game. Many of the free sites I used to read are gone now and I highly doubt this has caused an uptick in readership for paying magazines.

Does paying for a story raises the bar of quality of what you'll accept?

Yes. ADR was a website that didn't pay writers for a few years. Later, we decided to release a magazine (Amazon and POD) and pay writers $25 a story. We received about ten times as many submissions. We ended up turning down some excellent stories.

What has been your experience running a magazine in the crime genre, and why do you think there are fewer paying markets in Mystery than SF and Horror?

I enjoyed running the magazine and that's why it grew into All Due Respect Books. We still publish short stories in the form of collections by individual authors. About two years ago, it became clear that the magazine was taking up a significant amount of our time but was losing money. People in the crime fiction community were enthusiastic when we started and our first few issues sold a lot of copies. That didn't last. It was also a question of time. Running a magazine and a publishing house at the same time wasn't going to work. We chose the publishing house and that was the right choice. I think we have a long future ahead of us publishing excellent crime fiction while not going bankrupt. That's been my goal all along.

To respond to the second part of your question, SF and horror sound like the exception to the rule. It's difficult to run a magazine that pays writers. I don't know anyone who reads short story magazines who isn't a writer. And writers often submit work to publications they've never read. I don't want to blame anyone here--writers, readers, editors, "the industry," etc.--but, for whatever reason, short story publications have a tiny audience, and I don't see that changing.

Takeaways:

"Free hurts everything we do."

I agree. I've heard it time and time again, readers who wait for a book to drop to free or 99 cents. BookBub has made a living at it. But unless readers buy the next book at a profitable price, writing is not sustainable.

"I hope mystery isn't on the way out but I worry whenever I attend a mystery conference. Not many young readers."

This will be the subject of a future post. Bouchercon may not be the perfect con to become the "Comicon of Crime" ... but we NEED a "Comicon of Crime," that is hosted in one place or by one group.

"Crime/mystery doesn't have nearly the same level of organized fan activity."

This needs to change, but how to do it?

"I wanted to support not only the magazines, but my friends who were writing stories for them. But I found what I think most people find—I don’t like most of the stories."

This is a big problem. When I read EQMM or AHMM even the stories that aren't my cup of joe are of high quality. I can't say that about every magazine. You need a place to cut your teeth, but that doesn't mean the story should be published. There are sites like Fictionaut and others where you can share your work and get feedback.

"The markets are disappearing because nobody wants to pay for the magazines. Fewer and fewer people read. Even fewer want to pay for it."

Big problem. But it ties into the quality issue. I loved ThugLit's high quality level and bought print issues from Amazon (I hate reading e-books now that I need glasses). But it wasn't easy to subscribe. If a mag can't do print subs--and I get it, it's a LOT of work--they need an email mailing list, minimum, to alert readers of new issues.

"writers often submit work to publications they've never read."

Much to editors' chagrin. Live and learn, writers.

I went through the trouble of interviewing these editors to generate a discussion. Let's keep it civil, but what solutions do you see for these problems? Or do you think there's no problem at all?