2010, Aix-en-Provence, and I'm standing at a velvet rope in the Musée Granet. The rope is the only thing between me and a manual inspection of any painting in the gallery. I could have a right good art appreciation lesson before the guards swarmed. I stayed lawful and legit, but what if someone hadn't? What exactly would swarm? A story idea was born, and it started me on an unexpected path.

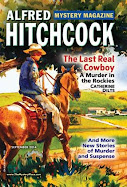

My first crime story. My first good crime story submitted, anyway. And my first acceptance in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.. There are ten more AHMM acceptances since that museum caper and 29 others out or headed your way. If by now you're thinking there will be math in this post, you're right.

|

| That first AHMM (2014) |

In all honesty, I didn't start out writing stories with any count goal in mind.

I was drafting an ambitiously doomed novel and hoping for credits to pad my queries. A fine plan, other than the doomed novel part.

The novel is shelved. The stories still trickle out a few per year. A person learns a few things on a path like that. The stories get better, I hope, or the author gets smarter. Talent is a factor in acceptance, but I'm being honest here. Luck gets involved. Tons of talented writers are out there writing tons of great stories. Not all of those catch an editor's eye.

Which mean it's important to share the wisdom. Math-style. Buckle up.

WORD COUNT IS NO ACCIDENT

We're a crime blog, so I'll filter the acceptances down to crime stories. I prefer to read printed stuff, so I'll filter again down to crime stories run or contracted to run in a print edition. I'll filter a third time for paying markets plus a conference anthology with charity proceeds. I want to see y'all printed and paid.

A print edition means print production costs. These constraints should inform a submission strategy. Precious few crime markets--or any markets--take novellas and novelletes these days. AHMM is one of those, to include the annual Black Orchid Award. Still, magazines have only so much room for magnum opus novellas. And for every long story, a print market needs multiple shorter stories to balance the issue. Not too short. Flash stories can create inverse balance issues. I go for the middle ground.

Oh, that Goldilocks zone, 3500 to 4500 words. Convert that word count to time, and you have a ten-ish minute, single-sitting read--nicely suited for my kind of character build and high note.

The average length in this group is 4,200 words. The eleven AHMM stories average 4,500, mostly off two longer stories featuring the same character. The eight in other markets average 3,800. Long pieces wear me out (more below), and shorter pieces are hard for me to nail. I don't spend much time on either.

READING IS CARING

Often, what goes without saying should be said most. Print markets have sample issues, either the current one or a back issue. Read them. Reading a market is essential to submission prep, or else I don't give the submission much chance. Respect-wise, markets can and should have editorial tastes. Not to sense a given market's taste is to be unprepared. As for AHMM, Managing Editor Linda Landrigan recently gave a lengthy interview to Jane Cleland here that is gold for anyone wanting to submit.

I'm molasses-in-winter slow at getting a piece ready. Six to nine months is warp speed. For AHMM, I'm usually in the eighteen month range before I feel confident enough to submit. Why rush something when AHMM prints six editions each year?

The numbers in red above are earlier manuscript versions floated to anthologies. These calls can be great motivators to get a draft finished. Deadlines are a thing with anthologies, whether I'm ready ready or not. Those early rejects did me a huge solid. A version of the French caper story went first to a MWA call. Rejection provided a chance to slow down and rewrite my AHMM breakthrough story.

STORIES OF DISTINCTION

Here's the thing about story variety: You have to be a varietal. At least bring a twist on something not done to death. If you're playing it tried and true, other someones have already bombarded these markets with a similar idea. I mean, distinctiveness is to break through that crowd. By side-stepping it.

Avoid–avoid–the first or easiest thoughts. People have been writing stories for a lo-ong time. That first idea has been done. But five or eight or so ideas down a brainstorming list is a prime nugget.

Inching out on a limb involves risk. Checking the mail has risk, too. Paper cuts. Wasp stings. Meteors. I say go for it.

"Two Bad Hamiltons and a Hirsute Jackson" (AHMM, 2015) is about twenty bucks in counterfeit. Twenty bucks. The difference maker is how the main character can't let an easily recoverable loss go. I've used hot chicken as an unhealthy religious experience, lottery audits as a stardom dream, and the surprisingly real phenomenon of walnut-jacking.

Another path to distinctiveness is approach, or how a story is told. Who takes center stage, how events are structured, what's the emphasis and slant. This path is inexhaustible. I'm character-centric. Premise follows, yin and yang. Plot and structure are the scaffolding. "The Cumberland Package" has a dark moment scene where main character literally disassociates for 412 words

. 412. In a short story. But whenever in angst I deleted that dark moment, the story fell apart. I kept the fugue, as to go down swinging. The story was a Derringer finalist.

Art theft and organized crime in the South of France isn't exactly original ground. To Catch a Thief got there first, among others. My thief in that French caper story had a turn of phrase, though, an Eeyore outlook on life but committed to the craft, like if Dortmunder had gone upscale and failed at that, too.

Speaking of Westlake, there's the dying art of style. I invest in a voice, broadly and for each story. I'm not afraid to use this for hijinks. But style is another risk. Style adds editing work. Maddening work, and style can backfire with an editor. AHMM's famed openness feeds my luck--but so does the energy put into each submission.

A MILLION CRIMES IN THE CITY

Murder in deft hands makes for awesome whodunnits.

Clues, red herrings, evidence, science, suspects. That's a lot. In that sense, I'm lazy. And also realistic. Writing a clever mystery isn't what draws me to the chair. Character is. Other writers bring more passion and skill to the whodunnit. I'll read those A-gamers' work and write in my wheelhouse.

This faux body count might surprise. Nine. That's on purpose. To paraphrase Raymond Chandler, murder is a means to another end, or it's a desperate reaction to something way out of hand. I start with the small change--relationship friction turned toxic, street robbery, drug muling, art capers that should've stayed clean--and see how out of hand things should get. If the character has to solve a crime, fine. Sometimes, I shake my lazy bones loose and write a mystery.

I've tried hard to learn from success and failure. I know first person is more my thing. Crawling inside a main character's head and way of speaking rewards my approach. I've learned to keep the vocabulary simple. A thesaurus is a great place to find the wrong words. And I track story stats so there's an objective way to keep improving. Okay, also I'm compulsive. But mainly the objectivity thing.

IN ALL

- Pros submit to pro markets. To compete, write and submit professionally.

- Don't rush a piece. It only gets one chance with a dream market. Be surer than sure you're researched and ready--ready ready--to click send.

- Don't settle on an easy plot or premise. If you've read it before, so has the editor.

- When in doubt, mid-range length is your friend.

- Read what you love. Write where your skills are.

If breaking in to these markets is your dream, keep dreaming. Don't be discouraged. Be intentional. Put in the work. I'm Exhibit A that there comes a moment. Mine was at that French velvet rope and wondering who might hop it.