The dream of the Old House is always the same. I’m walking through the woods with my dad; he’s alive and well. Robust. Immortal. I am both the boy I was—scrawny, quiet, hair so blond it’s almost white; and the man I became—fuller of face, quiet, the white now represented in my beard.

We’re walking through the scrub brush of West Texas, along one of the innumerable trails crisscrossing 150 acres of family land. We called this property the Old House. The name stood both for the hunting cabin someone had built there and for the land where it was situated. I’m not sure who named it that; maybe Sidney, my older brother with Down syndrome, took one look at it and said to my dad, “Pop, that’s an old house.” Sid loved going there to enjoy his comic books or listen to his cassette tapes; we all loved it. The Old House was to be our legacy.

|

| View from the Old House’s front porch on a snowy day. |

In the dream, my dad and I are just walking. We have our hunting rifles, but we’ve no wish to disturb the tranquility of these sacred woods. There’s the live oak tree where I nearly stepped on that copperhead. Over there, the entrance to the gully that gets progressively deeper as it runs westward, until you’re walking between lichen-covered boulders taller than houses. These are the woods where I learned at my father’s knee how to skin a buck and run a trotline, as the song says.

It is home; I am at peace.

And I wake up and remember. Dad has been gone since 2007, the victim of a rare bone cancer that began in his skull and touched his brain, and the Old House has been sold. In the final year of his illness, I tried in vain to persuade my dad not to sell the property.

James, no one has mowed the grass around the Old House. It must be waist-high by now. Don’t worry about that. I’ll mow the grass when I can. James, the water pump in the well house needs to be drained before the next freeze. Dad, I’ll take care of it. We need to get you better, first. I’m not going to get better, Son. I don’t want there to be fighting about who owns the Old House. We won’t fight, I promise you. We’ll share it. There needs to be money for Sidney’s care when I’m gone. This will help. Barbara will take care of Sid. Grace, Jon, and I will help her. Don’t sell the Old House, please.

|

| Scale model of the Old House as a birdhouse. |

But my dad’s mind was set, and the Old House was sold. It gave him a kind of peace I didn’t understand, but I eventually accepted. Then on November 15, 2007, Howard Wade Hearn—retired schoolteacher, huntsman, craftsman, veteran of the Second World War, and the best father a boy could hope for—passed away. My sister Barbara and her husband Larry took on the enormous responsibility of Sid’s care, just as they’d promised. The money from the Old House’s sale, in part, helped to pay for an additional bedroom, one just for Sid, and other renovations for my brother with special needs. Maybe that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise; maybe my dad made the right decision.

After the funeral, I returned to Georgetown, Texas, and settled back into my life. I was an attorney with a mortgage, a wife I loved, and a job I tolerated. With my dad’s passing and the Old House’s sale, childhood was officially over. I guess it had been for a while, since I was thirty-six. It might sound strange, but up until that time, I hadn’t felt like an adult. Not really. I hadn’t felt the burdens of life on my shoulders until I became my dad’s executor. I hadn’t felt old.

At fifty-one, I still have dreams about the Old House and the lessons I learned there. Even waking, I find myself thinking about sitting in deer blinds with my dad. We designed and constructed them ourselves, even putting one on telephone poles for a commanding view of a clearing frequented by deer. I sometimes use Google Earth, starting from the I-20 exit for Gordon, Texas, and I retrace from memory the highways and dirt roads leading to the Old House. I could bookmark the location, but I like finding it this way better; it’s like a treasure hunt where you find yourself.

|

| Destroyed by fire. |

Unless I win the lottery, I’ll probably never have enough money to buy the Old House and restore it to the family. Not in this economy. And even if I did, the actual Old House, the hunting cabin, has been destroyed by fire.

My sister, Barbara, and her sons discovered this on one of their occasional drives to West Texas from Fort Worth. Like me, they enjoy recalling the good ol’ days; unlike me, they live close enough to make the actual trip. Every so often, they’d drive by the property, look over the barbed wire fences, and remember. I’m thankful Sid wasn’t with them on that trip; though we miss him terribly, his passing in 2019 at least kept him from seeing his beloved cabin in ruins.

When Barb sent me photos of the rubble, the news was a gut-punch. There was the Old House’s tin roof collapsed over a burned-out husk, the roof I’d helped my dad put on during a windy day when we were both nearly blown off. Oddly, the flames didn’t reach the nearby shade tree, and the horse tire swing my nephews loved still hung from its branches, forlornly waiting for a rider. Seeing those photos, it was like I lost it all over again, and home never seemed more far away.

But sometimes, through writing, you can go home again. In “Home Is the Hunter,” my third entry in Michael Bracken’s Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir anthology, Joe Easterbrook returns to his roots in the wilderness of West Virginia. When Joe sets foot on the land he loved, his emotions are my emotions. When he recalls hunting with his father, his memories are my memories. And when he rebuilds his father’s hunting cabin, I’m holding the hammer.

This one’s for you, Dad. We’ll be together again one day, and we’ll take that walk.

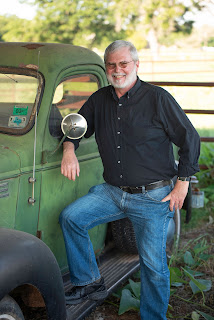

An Edgar Award nominee for Best Short Story, James A. Hearn writes in a variety of genres, including mystery, crime, science fiction, fantasy, and horror. He and his wife reside in Georgetown, Texas, with a boisterous Labrador retriever who keeps life interesting. Visit his website at www.jamesahearn.com.

Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir, vol. 3, is available here.