|

| © 2022 Joseph D'Agnese |

The cherry trees are blooming in my neighborhood as I write this.* Each year, my wife and I go out of our way to shoot as many photos of this spectacle as we can. We love watching the petals of the blossoms flutter across the yard like pink snow. Truly magical, and bittersweet, because by the time they begin dropping you know the show is nearly over. Indeed, by the time you read this, the bloom may well have ended.

Countless poets, writers, and artists in various cultures have drawn inspiration from those trees, and I’m no different. But because I’ve spent my life consuming crime novels and stories, my cherry-tree thoughts turn each year to the tale of a miserable exploited writer. The story comes not from a mystery or some work of literary fiction, but from one of my favorite cookbooks. Here’s the intro to the recipe on Cherry Pudding:

The cherry season is very short and one is always touched with sadness when it comes to an end. Sad too is the story of the song which is still passed on from one generation to another, ‘Les Temps des Cerises.’ In 1867 a young poet, Jean-Baptiste Clemént, sat in a shabby room watching at the death-bed of a friend. To cheer her a little he composed the first verse of the song, which he recited. The dying girl murmured, “It’s charming. Go on,” and he improvised the whole poem.

The girl died and the poet wept and the song was written. One day the poet suffered from the cold. He went to a publisher and exchanged his poem for an overcoat. Whilst the publisher made two million francs from the song the poet, in a moment of need, pawned the overcoat for fourteen francs, and that is all he got out of his lovely song.

|

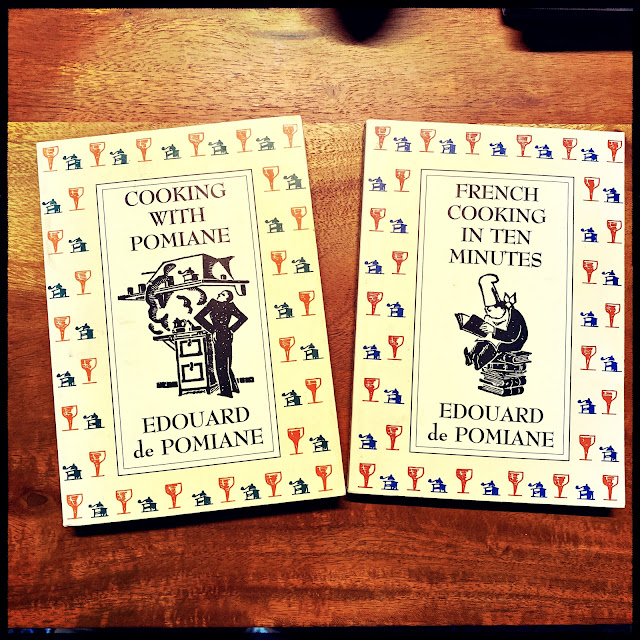

| The North Point Press editions. |

The author of these words is Edouard de Pomiane (1875-1964), who was a food scientist who lectured at the Pasteur Institute for 50 years. It’s hard to get a solid grasp of his biography. Articles say that his specialty was digestion or digestive juices, but he became a celebrity in France during the 1930s for radio shows in which he expounded clever ways to bring tasty dishes to the table. By the time he died at age 89, he had authored 22 cookbooks. The two that are most easily found in English translation are Cooking With Pomiane (the 245-page volume from which the cherry song story is excerpted) and French Cooking in Ten Minutes.

“Modern life is so hectic that we sometimes feel as if time is going up in smoke,” Docteur Pomiane tells us in the introduction to the latter, which clocks in at a mere 142 pages. “But we don’t want that to happen to our steak or omelet, so let’s hurry. Ten minutes is enough. One minute more and all will be lost.” He was speaking of the hectic life as it was perceived in 1930, when the book was published.

I love dipping into these small paperbacks from time to time, because they make me smile. The prose is refreshing, clear, and charming as heck. Pomiane was a master of the conversational tone. He wrote at a time when many French people were leaving the country for cities and the allure of steady office jobs. The shortages of WW-I were still well remembered. How could these proud people cook wholesome, traditional meals on schedules that were no longer their own to make?

On his radio program, Pomiane made his prejudices abundantly clear: French cooking as we’ve come to know it is unnecessarily complicated. Let’s leave fussy cooking to the professional chefs, if they feel they must cling to it. When you cook at home, keep it simple. That’s sensible advice for home cooks—and writers, to boot. The first chapter of Ten Minutes begins like this:

First of all, let me tell you that this is a beautiful book. I can say that because this is its first page. I just sat down to write it, and I feel happy, the way I feel whenever I start a new project.

My pen is full of ink, and there’s a stack of paper in front of me. I love this book because I’m writing it for you…

His first piece of advice:

The first thing you must do when you get home, before you take off your coat, is go to the kitchen and light the stove. It will have to be a gas stove, because otherwise you’ll never be able to cook in ten minutes.

Next, fill a pot large enough to hold a quart of water. Put it on the fire, cover it, and bring it to a boil. What’s the water for? I don’t know, but it’s bound to be good for something, whether in preparing your meal or just making coffee.

I’ve never been able to figure out if the famous cherry song he references, which is renowned as a song of political rebellion, is describing cherry blossom time, or the season some months later when the fruit is actually harvested. I suspect it is the latter. Pomiane appears to adore the fruit, because he gives us at least a half dozen cherry-based recipes. Clafoutis. Cherry Pudding. Piroshki with Cherries. A homemade cordial called Cherry Ratafia. And on and on. Here he is, describing the extraction of the Cherry Tart from the oven:

Don’t be discouraged. Cut the first slice and the juice will run out. Now try it. What a surprise! The tart is neither crisp nor soggy, and just tinged with cherry juice. The cherries have kept all their flavor and the juice is not sticky—just pure cherry juice. They had some very good ideas in 1865!

|

| © 2002 Joseph D'Agnese |

Another food scientist-writer would have lectured us on how butter melts in the pate brisee and creates air bubbles and blah blah blah, snooze snooze snooze. Pomiane knows the science. He also knows we don’t need to know it. He focuses instead on telling details and imagery that you cannot shake from your mind. When the flesh of cherries are broken, he says, “they seem to be splashed with brilliant blood.” And indeed, in the song, the color of the cherries came to symbolize the blood of rebellion.

That should not surprise those of us who have read widely in the mystery genre, where death is often paired with food. But when I read Pomiane, I sometimes wonder if I am reading a cookbook or watching a piece of Grand Guignol theater. In the larger of the two books, he recounts a 1551 legend about a jealous baker who finds his wife in the kitchen with a younger man.

He’s just an assistant I hired while you were out of town! she tells hubs.

“Very well,” the husband says, “I am prepared to believe your story, but if this young pastry cook cannot prepare eighteen cakes immediately I shall stab him with this cutlass and then slit your throat, Madame.”

The young man prays to St. Madeleine for guidance, and lo and behold, miraculously turns out the legendary cakes that bear her name.

I suspect that Docteur Pomiane’s adoring fans would have been far more shocked if they knew a little-advertised truth about the mustachioed, grandfatherly man who crafted these best-selling books on cuisine. You see, Pomiane was born in France, but his birth name was Edouard Pozerski Pomian. His parents were immigrants. Quelle horreur! The man who taught the 20th century French to cook, the man whose ideas many say influence farm-to-table French chefs to this very day, was of Polish descent.

A happy spring to you all!

The cherries seen most often in one’s neighborhoods are ornamental, not fruit-bearing, trees. On occasion, if weather and pollinators align properly, an ornamental might well bear tiny fruit, which are fit for crows, not humans. Ask me how I know.

See you in three weeks!

Joe

.jpg)