This isn’t new territory for me—I’ve edited six published anthologies, including, most recently, The Eyes of Texas: Private Eyes from the Panhandle to the Piney Woods (Down & Out Books), and another (Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir) that’s scheduled for publication next year. I also co-created and co-edit (with Trey R. Barker) the invitation-only serial novella anthology series Gun + Tacos, and I’m currently reading submissions for Mickey Finn 2 and the second season of Guns + Tacos, and I’ve begun work on yet another anthology to be named later.

There is a distinct difference between reading slush for my own anthologies and reading slush for Black Cat Mystery Magazine. The most obvious distinction is the type of stories appropriate for each. My anthologies have all been themed, and most have favored hardboiled, noir, and/or private eye stories. The stories in BCMM are more representative of the many subgenres of mystery.

The second distinction is the decision-making process. With my anthologies I make the final decisions and the anthologies succeed or fail due to those decisions. BCMM, on the other hand, has two decision makers. Though John Betancourt, as publisher and senior co-editor makes final decisions, the co-editorship is structured such that every accepted story has been approved by both editors.

Though there’s not yet any interesting statistical information to report on my most recent editorial efforts, the seventy-four stories in my first five anthologies earned seven award nominations (Anthony, Derringer, Edgar, Shamus, etc.) and four “Other Distinguished Mystery Stories” or “Honorable Mentions” in annual best-of-year anthologies.

BONA FIDES

All of the above is to establish my bona fides before this:

Editors often discuss the “indefinable something” that separates an accepted submission from a rejected submission. We sit on panels and discuss plot and setting and characterization. We debate whether certain words—such as Dumpster/dumpster—have lost their trademark status and can now be rendered all lowercase. We arm wrestle over the use or non-use of the Oxford comma. We do all of these things when talking to writers and amongst ourselves, but we never seem to mention aloud one of the most telling signs that a manuscript will be rejected.

The manuscript itself.

Sure, we often tell writers to follow Shunn or some similar format, but the appearance of a manuscript when printed on paper isn’t all that we see. With the vast majority of manuscripts now submitted as Word documents, I’ve discovered how little many writers know about using one of the primary tools of their trade.

Sure, we often tell writers to follow Shunn or some similar format, but the appearance of a manuscript when printed on paper isn’t all that we see. With the vast majority of manuscripts now submitted as Word documents, I’ve discovered how little many writers know about using one of the primary tools of their trade.And, perhaps not surprisingly, the writers least familiar with Word also seem to be the writers most likely to have their submissions rejected.

If I open a file and discover a return at the end of every line as if the story were written on a typewriter, or if I see the title centered on the page through the use of a zillion spaces, or if I see any of several other signs that the writer has not mastered the fundamentals of Word, I’m already negatively predisposed toward the manuscript.

Why?

Because the writing often displays the same inattention to detail.

I read anyhow because I am sometimes surprised. Sometimes.

KING OF THE WORLD

If I were king of the world, the czar of publishing, or in some other authoritarian position to impose my will upon writers, I would do the following: Make it mandatory for every writer to master the basics of Word.

Perhaps we could start by having every creative writing program offer a mandatory class in the use of Word as part of the degree plan. Perhaps we could have every writing conference offer a mandatory seminar in the use of Word. Perhaps we could have every critique group treat themselves to an annual refresher course from their most experienced tech-savvy member (or from someone outside the group, if appropriate).

Perhaps, and this may be a radical thought, we could suggest that writers and would-be writers read the instruction manual, use the help menu, or use a search engine to find instructions on the internet for how to do things such as indent a paragraph, center a line of text, insert an em-dash, insert headers and automatically number pages, and do any of a number of other things that should already be part of a writer’s skill set.

Love it or hate it, Word is the de facto word processing program, and it is a fundamental tool of the trade. If you don’t know how to use the tools of your trade, you hobble yourself. Sure, a brain surgeon might be able to repair your aneurysm with a pipe wrench, but how confident would you feel on that operating room table when he opened up his toolbox?

So, before I’ve even read a word of your manuscript, show me that you know how to use the tools of your trade. Then show me you can write.

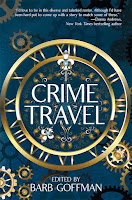

Recently published stories include: “The Town Where Money Grew on Trees” in Tough, November 5, 2019, “The Show Must Go On” in Black Cat Mystery Magazine #5, “Who Done It” in Seascape: The Best New England Crime Stories 2019 (Level Best Books), and “Love, or Something Like it” in Crime Travel (Wildside Press).

Earlier this month subscribers to Guns + Tacos received episode 6 of the first season, “A Beretta, Burritos and Bears” by James A. Hearn. Subscribers also received a bonus story that I wrote, “Plantanos con Lechera and a Snub-Nosed .38.” If you want to read all six episodes and the bonus story, there’s still time to subscribe!