First Alec Baldwin gets kicked off of an airplane for playing it, and I ask my kids (adults, but still kids) “hey, what’s that game all about.” They roll their eyes.

The next thing I know I am bombarded by the game. Driving from Washington, D.C. to St. Louis for Christmas Eve my kids are playing the game on their cell phones, on line (thanks to 3 and 4 G) with their friends back in Washington D.C. Then on Christmas night, with my wife’s family in Vincennes, Indiana, I look around the room and six different family members are clicking on their phones playing with people either across the room or across the country. Well, a bit of a disruption for Christmas, but as Mr. Baldwin observed on Saturday Night Live, at least it’s “one of those intelligent games.”

All of this got me to thinking about what kinds of games appeal to what kinds of people. As to the aforementioned Words with Friends, I am not bad at coming up with suggestions for words for my kids as we drive across the country. But my role is, at best, "of counsel" -- the game holds no real interest for me.

Several years ago a query was posted on the Readers’ Forum at the Mystery Place, the forum hosted by Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. The question posed was how many of the readers of those magazines were also cross-word puzzle aficionados. A number of readers reponded that they were cross-word fans, but a very prominent contributor, Jon Breen (who for over thirty years wrote The Jury Box for EQMM and who is a heralded author of mystery short stories and novels) replied that while he didn’t do many crosswords, he was a big fan of Sudoku puzzles. “Aha,” I thought. “I have that in common with Jon.” Something about how my mind works doesn’t adapt all that well to crossword clues. And I am terrible at chess – one of the worst chess players ever. But Sudoku puzzles – not only can I solve them, I often seek them out for intellectual diversion.

What’s the attraction? Well, principally it seems to me that the Sudoku puzzle runs very close to the guidelines for classic whodunit mystery stories, ‘fair play’ mysteries, which are my favorites both to write and to read. The Sudoku puzzle, like a golden age mystery, is (literally) walled off. All of the suspects are known, and the game is a contained one of “fair play” since enough clues are always revealed so that a diligent player has the opportunity (if not always the ability) to glean the culprit that must necessarily occupy each box. Some of the relationships behind the various boxes are not in the first instance obvious, but all ultimately can be deduced (albeit often by those with abilities beyond my pay grade).

Thinking back to Jon’s answer on the Mystery Forum, it occurred to me that perhaps the types of games a person likes bears a rough relationship to the type of mystery stories that person likes. I suspect, as an example, that a reader who thrives on historical mysteries might be more attracted by crossword puzzles – where solutions rely on the player’s ability to apply knowledge of outside events to the puzzle. Whether or not this is true, I know that one of the reasons I like Sudoku puzzles is that they come about as close to a fair play mystery as you can get in game form.

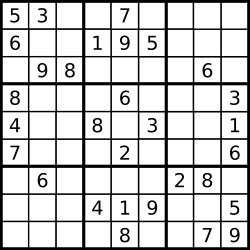

Background for anyone who somehow is new to the game: A Sudoku puzzle is a variant of a Latin square, that is, a grid with n different symbols, each occurring exactly once in each row and exactly once in each column. The classic Sudoku puzzle contains nine rows and nine columns. Each row contains nine number squares. The puzzle itself is also divided into nine internal boxes of nine squares each. The goal of the game, for those not familiar with the process, is a simple but maddening one: Each row contains the numbers one through nine, as does each column. And every number can appear only once in each row, each column, and each internal box of nine squares. For each puzzle there is one, and only one, solution.

|

| Howard S. Garns |

The USNET news group has reportedly determined that there are 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 possible puzzles that can populate a nine by nine Sudoku grid. But in each board, if the minimally required hints are given, there can be only one solution, only one number that can occupy each box. And that is the essential similarity, it seems to me, that links the puzzle and classic fair play mystery stories. The art of constructing each is to fairly give enough clues that the mystery demonstrably can be solved. And the challenge in constructing both a difficult fair play mystery and a difficult Sudoku is not to reveal the answer, but to hide it. To achieve the most diabolical level of success requires the designer of the game, and the author of the story, to give all of the information that is necessary but to do so in a way that will hide the actual solution. In other words, the game is not “show and tell,” it is “hide and seek.”

|

| Professor James Moriarty |

Unlike mystery stories there are, of course, more precise constraints on the number of clues that must be given in a Sudoku. While it apparently cannot be mathematically proven, the supposition among math theorists is that a full Sudoku grid of 81 boxes must minimally contain at least 17 filled in “clue” boxes in order for the final solution to be both discernible and completely unique. But the fact of “uniqueness” is, again, an attribute shared with a golden age mystery – in each, if you pay attention, and engage the deductive process, there is one and only one solution.

Needless to say there are some Sudoku puzzles that are so difficult that they can only be solved by logical reasoning that is too complex for most human minds. In the world of Sudoku puzzles this has spawned websites, the development of computer programs, formulae and the advent of discussion groups, all aimed at developing tools to decipher the seemingly impossible. But in at least one respect the mystery story has the upper hand. When a Sudoku completely baffles the player the only option (if your game is published in a periodical) is to wait a day to read a published solution (or hit that “hint” button if you are playing electronically.) But with a mystery story you can just go on reading and wait for the likes of Sherlock Holmes, Miss Marple, Poirot, Nero Wolfe, or Ellery Queen, to offer up the solution that has stumped the mere mortal reader.