Showing posts with label mysteries. Show all posts

Showing posts with label mysteries. Show all posts

21 July 2013

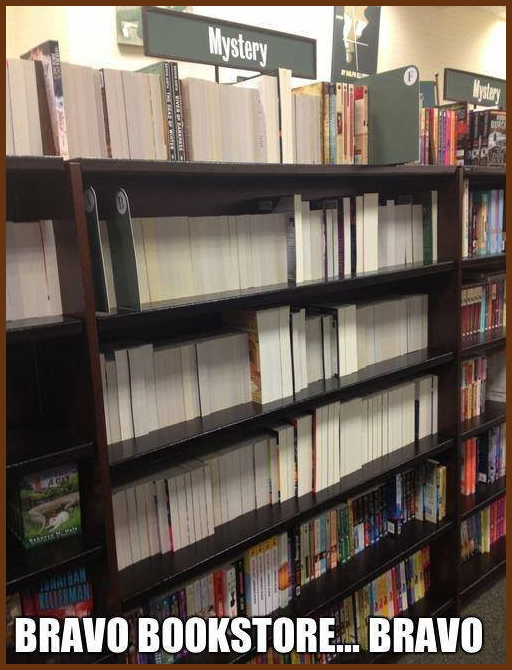

Mystery Bookshelves

by Leigh Lundin

Labels:

bookstores,

Leigh Lundin,

mysteries

Location:

Kloof, South Africa

28 June 2013

Mother Hubbard has a Corpse in the Cupboard

by Dixon Hill

And, evidently, when “Mother Hubbard” is a guy from India, those corpses can really start to pile up!

A book review by Dixon Hill

I read, once, that in the best mysteries the murdered body is usually discovered by page seven. Fran Rizer beats that count in Mother Hubbard has a Corpse in the Cupboard, when the first body is discovered on page three. The cupboard, where said corpse resides, is a pantry/storage room formed by canvas walls separating the kitchen space from the dining area in a county fair food-tent known as Mother Hubbard’s Beer Garden.

Calamine Lotion “Callie” Parrish (the series protagonist) has convinced her two friends – Jane and Rizzie — to join her for a ‘Ladies Day Out’ at the Jade County Fair, and naturally, the trio stops for a fair-food repast. But, a good time is not to be had by all, when Callie gets a troubling call on The Bat-Phone (er…I mean: on her bra-phone – I won’t explain more, except to say that James Brown has never made me laugh so hard!), and Jane literally stumbles over the corpse without knowing it.

Calamine Lotion “Callie” Parrish (the series protagonist) has convinced her two friends – Jane and Rizzie — to join her for a ‘Ladies Day Out’ at the Jade County Fair, and naturally, the trio stops for a fair-food repast. But, a good time is not to be had by all, when Callie gets a troubling call on The Bat-Phone (er…I mean: on her bra-phone – I won’t explain more, except to say that James Brown has never made me laugh so hard!), and Jane literally stumbles over the corpse without knowing it.How can someone UNKNOWINGLY stumble over a corpse?

Well, Jane – Callie’s best friend since childhood – doesn’t see too well. In fact, she doesn’t see at all, as she was born without optic nerves. And, for those who don’t know: Jane earns her living as a phone sex operator and has only recently given up shoplifting. She’s also somehow become engaged to Callie’s brother, Frankie, (Even Callie isn’t sure how THAT happened!),and now Jane thinks she might be pregnant.

Callie’s other BFF, Rizzie Profit, is “ Gullah and gorgeous.” Though she and her extended family hail from Surcie Island – a fictional member of the real “Sea Island” chain off the coast of South Carolina, perhaps loosely modeled after Saint Helena Island -- Rizzie owns the Gastric Gullah Grill in St. Mary, Callie’s mainland hometown. It’s there that Rizzie works with her grandmother, Maum, and her 14-year-old brother, Tyrone.

The bad news on the bra-phone is that Maum landed in the hospital with a heart condition and a broken hip. A worried Tyrone is at her side, but Maum is terrified as well as in and out of consciousness. The teen needs his older sister to lean on.

The bad news on the bra-phone is that Maum landed in the hospital with a heart condition and a broken hip. A worried Tyrone is at her side, but Maum is terrified as well as in and out of consciousness. The teen needs his older sister to lean on.Exit Rizzie, to the hospital, while Jane and Callie wait for the cops.

At this point, I’ll quit the play-by-play and level with you:

As you may have guessed from my lead-in, it’s possible to read most of this book as a light-hearted romp through what some might call the Southern Mystery Chick Lit genre, but there’s a dark streak that runs straight down through the center of this one. And, if you don’t watch out, you just might find it jerking more than a few tears out of your eyes.

Ms. Rizer has done a marvelous job of balancing the dark with the light – in more ways than one. And, I can honestly say that I was laughing out loud by the end of the very first paragraph. But, that humor is offset by the poignant loss of a loved one in the book.

Until now, no “living” character who died within the confines of the series time-frame experienced a natural death. In fact, this is the first character who actually dies on the written page; all the others were killed off-stage and discovered later. Callie’s there for this passing, however.

No slouch at writing, Ms. Rizer took this opportunity to do what I can only call “an excellent job” of comparing Callie’s feelings of personal loss when such a close friend dies, and the feelings she deals with on a daily basis while working on the dead as a funeral parlor cosmetologist.

In fact, the comparison is quite stunning.

Which should come as no surprise

Because long-time readers of the series should have noticed, by now, how much Callie, herself, is a walking dichotomy.

|

| Okay, this isn't really Callie, but she's evidently her understudy. |

Not that she disliked her childhood; she clearly enjoyed it. And, she obviously loves her father, even though the guy is pretty overbearing (at least, that’s what I’d call a man who won’t let his thirty-something daughter drink a couple beers in front of him). Callie also puts up with a lot from her brothers, though she seldom has a bad word to say about any of them.

So, perhaps it’s not surprising that she never explains what caused the dissolution of her marriage. All readers know is that Donnie, her ex-husband, did something “that made me divorce him” and that she “didn’t catch him doing the dirty on the dining room table like Stephanie Plum did her husband.”

We know she divorced Donnie and simultaneously quit her job as a kindergarten teacher to move back to her hometown and become a cosmetician at the local funeral home – an action she sums up by quipping that she traded a job working with five-year-olds who wouldn’t take naps or lie still, for one in which she works with dead people who don’t move.

Faithful readers know, of course, from previous books, that Donnie is a surgeon and Callie’s teaching job put him through med school, and that Donnie is an ass (he makes that clear though his own actions). But, on the subject of the catalyst for her divorce – this thing that Donnie did -- she is mute.

This silence, issuing from the normally gregarious Callie, is haunting. It hints at a maturity that’s usually missing from her light-hearted chatty persona, and tells a thoughtful reader that there are deeper waters running through this woman’s silent heart.

Callie is more than she reveals to us on the written page, except in those rare instances when she’s too concerned with other things to keep up the act. Then we catch a fleeting glimpse of a different person – one which Callie is sure to dismiss with some lighthearted comments a few pages later.

Her behavior in a tight spot, for instance, often belies her daily air-head pretension. In this book, when Callie realizes that the thing Jane stumbled over in Mother Hubbard’s is a body with a bullet hole in it, she quickly hands her car keys to Rizzie, directing her to drive her (Callie’s) mustang to the hospital to comfort her brother and grandmother. Then she contacts the police and calls a waiter over to explain the situation – all while trying to calm a near-hysterical Jane. Later, it becomes clear that she’s carefully orchestrated the situation in a manner that permitted Rizzie to take care of her personal emergency, while Jane and Callie remained at the beer tent so that responding police officers could interview the two of them.

She even exerts a thought-out limited influence, in order to keep the crime scene from being disturbed before investigators arrive. These are the actions of a quick, orderly and intelligent mind, yet they’re performed by a woman who seems compelled to pretend that she’s a bubble-head concerned with little more than personal appearance.

This is what makes me suspect Callie’s hiding something from us, for some reason. I can’t help thinking that this hidden reason deals in some way with that thing Donnie did. Whether or not it’s a direct cause and effect relationship, it seems apparent that there’s some relation between her break with Donnie and the emotional insecurity that drives her to wear an inflatable bra and act in childish ways.

Or, perhaps I’m wrong. Perhaps, as she claims, Callie’s just trying to make her outside resemble the maturity within, but is stymied by a body that looks as if it belongs to a girl just past puberty. Maybe she’s one of those unfortunate people who suddenly seem to physically jump in age from 16 to 47 almost overnight – though the change is often tacked up to hard living and loneliness, by the person’s peers.

But, we readers (or, at least, I) don’t want to see this happen to Callie. Instead, we want her to meet a man who will tell her – to borrow a phrase from Bridget Jones's Diary – “I like you … just as you are,” while unsnapping that silly bra and sliding her out of those padded panties for the last time.

Not that Callie has to be “rescued” by a man. We just want to see her snap out of it. This is part of the series allure: I want Callie to realize she doesn’t need to pretend to be somebody she’s not – that she’s a smart, industrious, and pretty terrific young woman. And, if her dad and brothers can’t handle that fact, it’s not her problem. They’re the ones who need to find a way to deal with it.

I can’t help thinking that when Callie realizes this, she’ll finally be the full-grown woman she’s striving to become – both inside and out. Beating my hands on my thighs while I read the books, wanting to tell her that’s the answer, wanting to help her quit this whipsaw effect between adolescence and adulthood, that’s what drives me crazy about the Callie character.

Yet, in some strange way, this personal fallible is also what brings Callie’s character to life.

And, if I’m fully honest: It’s also what makes me love her.

Not that there isn't a satisfying mystery here …

… all I’s dotted and T’s crossed by the end of the book. Rizer proves her mettle by presenting us with such a gripping story of personal loss, as a loved one fades slowly away, yet she never lets this overpower or derail the mystery. A difficult feat, but one she handles with a hand so deft I sometimes found myself laughing through misty eyes, as I tried to weigh the suspects:

Jetendre “J.T.” Patel: He’s the Mother Hubbard concession owner, who was born in India and immigrated as a child with his parents. He met Callie after she discovered the corpse, but it’s her body he’s thinking of. Or, is it?

Nila and Nina: Identical twin spinsters, one of whom has finally succumbed to old age. The survivor wants to be sure she and her dead sister are coifed and dressed identically for the viewing and funeral—complete with a costume change between the two events.

When a mysterious man arrives, claiming to have been an old flame of the dead woman, but begins dating the living one, Callie’s suspicions are raised, particularly after she learns that the funeral director from the twins’ hometown wants to know why the dead sister is being buried by an out-of-town firm.

As the book progresses, with no visible ties between the murder victims, another question looms large: Who defaced caskets at the mortuary where Callie works, keeps smoking cigarettes out front of Callie’s place late at night, and riles her normally placid dog, Big Boy, until the angry Great Dane lights out after the culprit only to return with his tail between his legs?

When a second murder victim turns up, the evidence strongly points at Rizzie’s brother, Tyrone. And, while Callie’s friend, Sheriff Wayne Harmon, wants to give the teenager a break, the local lawman’s sympathy is checked by concerns that it seems the boy has fallen in with the wrong gang – and by the fact that the boy, who’s a crack shot, claims to have thrown away his hunting rifle, which is the same caliber as the murder weapon.

But, if Tyrone is the perp, why was the family van torched in the hospital parking lot?

Callie fans needn't fear: Their favorite inflatable-bra detective is on the case!

.jpg) |

| Fran Rizer (center) at a reading with "Callie" and "Jane" |

See you in two weeks!

--Dix

14 June 2013

Two Guns 2013

by Dixon Hill

Summer-Time Reflections on Writing, Route 66, and the Digital Interstate

We took a family vacation last week. The photo below-right shows my son, Quen, about ten minutes after he saw the Grand Canyon for the first time -- an event I missed.

Reaching the Canyon’s south rim just before sunset, we found nowhere to park. So, I let my wife and kids out of the car, then orbited the parking lot until a slot opened up.

Reaching the Canyon’s south rim just before sunset, we found nowhere to park. So, I let my wife and kids out of the car, then orbited the parking lot until a slot opened up.

When I caught up to them, and asked Quen what he thought of the canyon, he told me, “It doesn’t look real!” A few minutes later, he dropped to his hands and knees, then shoved one arm far out, through the space beneath the fence seen here. Feeling around out past the rocks, his fingers closed on empty air. He turned his head, looking up at me: “It IS real!”

I took this photo after he stood again. And, it took him a bit longer to stand, than it had to drop down. Note that he’s gripping the guard rail, and his face reflects the danger of the drop behind him. He hadn’t been worried until he stuck his hand through that fence and felt the empty space beyond. Until then, that incredibly long drop to the canyon floor hadn’t seemed threatening.

The threat itself, however, had always been there. The threat hadn’t changed; my son’s perception had.

Digital Disbelief

Essentially, Quen had fallen victim to a sort of inverse optical illusion. As a ten year old, he’s been raised in a media age that bombarded his eyes and brain with hundreds, maybe even thousands, of images of the Grand Canyon before he had a chance to see the “McCoy”. And, many of these images had been presented in high definition; they looked just as real as the Grand Canyon that now loomed inches beyond his feet.

When my son stuck his hand through that guardrail fence, the thing I believe he was feeling for was a screen. Because, hi-def images appear on screens -- and those screens are often very large. If you’ve been to an IMAX theater, you know what I mean.

It was only after my son reached for a screen, but found empty space instead, that the deep chasm before him became real. Until that moment, he wasn’t afraid of falling into the Grand Canyon. But, in that instant, he realized -- this time! -- the abyss he was seeing, was really there.

I can’t help but think there’s an important lesson here, for those writing in this digital age. A warning, perhaps, about the changing nature of reality-perception among young readers. A reality-perception we’ll have to come to grips with, and help readers overcome, if our writing is to have lasting meaning.

The Route to Realization

Our family trip itinerary was a bit a on the loony side. Or, perhaps I should say it was a little over-full. I picked up a rental SUV at noon on Tuesday, and we left town two hours later, planning to visit the Grand Canyon, Wupatki (Indian ruins), Sunset Crater (a dormant volcano), Meteor Crater, the Painted Desert, and the Petrified Forest, all while getting a little driving and photo op time on Route 66 -- before dropping the SUV back at Sky Harbor Airport in Phoenix by noon on Friday.

While all these spots can be “seen” on the cartoon map at the top of this post, that image is deceptive: our trip would actually take us more than 500 miles round-trip. Phoenix to the Canyon is 225 miles; Grand Canyon to the “Painted Forest” -- as my wife now calls the national park that combines the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest into a single driving tour -- is another 200. And, unbeknownst to the kids, my wife and I had also spotted a contemporary ghost town on our route, which we wanted to work in if we could somehow find the time.

Our Day One route (orange) took us from Phoenix through Flagstaff and up to the south rim of the Grand Canyon, which -- as mentioned previously -- we reached just before sundown. We spent that night in Tusayan, just outside the canyon park entrance. Day Two (Green) took us back to the Grand Canyon, then on to Wupatki and Sunset Crater, back through Flag and over to a Best Western for a night in Winslow. Day Three (orange and green) we planned to forge on to the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest, then follow highway 180 up, to take Route 66 through Winslow on our way to visit Meteor Crater before getting back on I-40 and turning south in Flagstaff to head home.

And, that’s pretty much what we did. The only thing we dropped was Meteor Crater, because most of us had seen it before, and the kids were too pooped to do any more walking by the time we’d finished with the “Painted Forest”.

We’d seen a PBS special on “The Mother Road” a few months back, however, and the kids were interested in seeing Route 66, so I used this opportunity to get a little more driving time on the remains of that original old highway. Plus, Mad and I had our little surprise for them.

If you look at the highway map, you’ll see a spot that’s about half-way between Flagstaff and Winslow, labeled “Two Guns”. This is the site where the small town of Two Guns, Arizona once straddled a concrete bridge spanning Canyon Diablo. Route 66 passed over this bridge and Two Guns, established in the late 1800’s, survived -- prospering during the early 1900’s as a tourist stop on The Mother Road -- until I-40 was built about three-hundred yards to the north. The town sputtered on into the mid-60’s, then fell and restarted until it finally died out in the mid-70’s.

Below, you’ll see a shot of the entrance to a sort of “zoo” built to lure tourists to Two Guns.

The zoo originally sat farther south, but was moved -- along with the gas station and general store -- to a location more advantageous to travelers on I-40. I took this shot with my back not 200 yards from traffic speeding down I-40, but the building stands in ruins as mute testament to the fact its “Mountain Lions” logo, once darkly painted in bold, couldn’t stop cars traveling 75 to 85 miles per hour. The Welcome sign no longer serves any purpose.

Sign Post Up Ahead

And that got me thinking:

How can we, as writers, capture and hang onto current and future consumers of our printed goods as these changes sweep over us? Many of my SS colleagues have taken first-steps along this path; I’ve read much of their work -- short stories and novels, both -- in electronic versions I bought online. But, is this enough? Are we thinking the right way? Or, are we victims caught in a pre-digital paradigm?

L.A. Noire, introduced in 2011, was the first video game to be shown at the Tribeca Film Festival, and it received accolades for its advanced storytelling.

According to Wikipedia: “L.A. Noire is set in Los Angeles in 1947 and challenges the player, controlling a Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officer, to solve a range of cases across five departments. Players must investigate crime scenes for clues, follow up leads, and interrogate suspects, and the players' success at these activities will impact how much of the cases' stories are revealed.

“The game draws heavily from both the plot and aesthetic elements of film noir, stylistic films made popular in the 1940s and 1950s that share similar visual styles and themes, including crime and moral ambiguity. The game uses a distinctive color palette, but in homage to film noir it includes the option to play the game in black and white. Various plot elements reference the major themes of gum-shoe detective and mobster stories such as Key Largo, Chinatown, The Untouchables, The Black Dahlia, and L.A. Confidential.”

What does this mean to us, as mystery writers?

And, I wonder: Is the next “True Classic” -- a modern work that will be experienced and studied down through the ages -- even now being keyed-in by some Shakespearian software writer working for a video game manufacturer?

The folks who ran Two Guns were intelligent, industrious, and worked hard to save their livelihoods. But, that didn’t keep them from being literally “kicked to the curb” by a new technology that they couldn't figure out how to deal with.

I’ve not made any suggestions for the best way we can position ourselves, as our way of thinking is swallowed whole by this new one. I can’t really come up with any. And, I know a lot of people have been contemplating, and still are contemplating, this problem.

But, Two Guns serves as a grim reminder: We need to figure it out SOON, or the signpost up ahead might well look like the one at that once-bustling Route 66 stop.

We took a family vacation last week. The photo below-right shows my son, Quen, about ten minutes after he saw the Grand Canyon for the first time -- an event I missed.

Reaching the Canyon’s south rim just before sunset, we found nowhere to park. So, I let my wife and kids out of the car, then orbited the parking lot until a slot opened up.

Reaching the Canyon’s south rim just before sunset, we found nowhere to park. So, I let my wife and kids out of the car, then orbited the parking lot until a slot opened up.When I caught up to them, and asked Quen what he thought of the canyon, he told me, “It doesn’t look real!” A few minutes later, he dropped to his hands and knees, then shoved one arm far out, through the space beneath the fence seen here. Feeling around out past the rocks, his fingers closed on empty air. He turned his head, looking up at me: “It IS real!”

I took this photo after he stood again. And, it took him a bit longer to stand, than it had to drop down. Note that he’s gripping the guard rail, and his face reflects the danger of the drop behind him. He hadn’t been worried until he stuck his hand through that fence and felt the empty space beyond. Until then, that incredibly long drop to the canyon floor hadn’t seemed threatening.

The threat itself, however, had always been there. The threat hadn’t changed; my son’s perception had.

Digital Disbelief

Essentially, Quen had fallen victim to a sort of inverse optical illusion. As a ten year old, he’s been raised in a media age that bombarded his eyes and brain with hundreds, maybe even thousands, of images of the Grand Canyon before he had a chance to see the “McCoy”. And, many of these images had been presented in high definition; they looked just as real as the Grand Canyon that now loomed inches beyond his feet.

When my son stuck his hand through that guardrail fence, the thing I believe he was feeling for was a screen. Because, hi-def images appear on screens -- and those screens are often very large. If you’ve been to an IMAX theater, you know what I mean.

It was only after my son reached for a screen, but found empty space instead, that the deep chasm before him became real. Until that moment, he wasn’t afraid of falling into the Grand Canyon. But, in that instant, he realized -- this time! -- the abyss he was seeing, was really there.

I can’t help but think there’s an important lesson here, for those writing in this digital age. A warning, perhaps, about the changing nature of reality-perception among young readers. A reality-perception we’ll have to come to grips with, and help readers overcome, if our writing is to have lasting meaning.

The Route to Realization

Our family trip itinerary was a bit a on the loony side. Or, perhaps I should say it was a little over-full. I picked up a rental SUV at noon on Tuesday, and we left town two hours later, planning to visit the Grand Canyon, Wupatki (Indian ruins), Sunset Crater (a dormant volcano), Meteor Crater, the Painted Desert, and the Petrified Forest, all while getting a little driving and photo op time on Route 66 -- before dropping the SUV back at Sky Harbor Airport in Phoenix by noon on Friday.

While all these spots can be “seen” on the cartoon map at the top of this post, that image is deceptive: our trip would actually take us more than 500 miles round-trip. Phoenix to the Canyon is 225 miles; Grand Canyon to the “Painted Forest” -- as my wife now calls the national park that combines the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest into a single driving tour -- is another 200. And, unbeknownst to the kids, my wife and I had also spotted a contemporary ghost town on our route, which we wanted to work in if we could somehow find the time.

Our Day One route (orange) took us from Phoenix through Flagstaff and up to the south rim of the Grand Canyon, which -- as mentioned previously -- we reached just before sundown. We spent that night in Tusayan, just outside the canyon park entrance. Day Two (Green) took us back to the Grand Canyon, then on to Wupatki and Sunset Crater, back through Flag and over to a Best Western for a night in Winslow. Day Three (orange and green) we planned to forge on to the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest, then follow highway 180 up, to take Route 66 through Winslow on our way to visit Meteor Crater before getting back on I-40 and turning south in Flagstaff to head home.

|

| Quen: “Standing on a corner in Winslow, Arizona.” |

We’d seen a PBS special on “The Mother Road” a few months back, however, and the kids were interested in seeing Route 66, so I used this opportunity to get a little more driving time on the remains of that original old highway. Plus, Mad and I had our little surprise for them.

If you look at the highway map, you’ll see a spot that’s about half-way between Flagstaff and Winslow, labeled “Two Guns”. This is the site where the small town of Two Guns, Arizona once straddled a concrete bridge spanning Canyon Diablo. Route 66 passed over this bridge and Two Guns, established in the late 1800’s, survived -- prospering during the early 1900’s as a tourist stop on The Mother Road -- until I-40 was built about three-hundred yards to the north. The town sputtered on into the mid-60’s, then fell and restarted until it finally died out in the mid-70’s.

Below, you’ll see a shot of the entrance to a sort of “zoo” built to lure tourists to Two Guns.

The zoo originally sat farther south, but was moved -- along with the gas station and general store -- to a location more advantageous to travelers on I-40. I took this shot with my back not 200 yards from traffic speeding down I-40, but the building stands in ruins as mute testament to the fact its “Mountain Lions” logo, once darkly painted in bold, couldn’t stop cars traveling 75 to 85 miles per hour. The Welcome sign no longer serves any purpose.

Sign Post Up Ahead

And that got me thinking:

- Route 66 vs. the Interstate

- Print Writing vs. the Digital Interstate we call the World Wide Web.

- And, the impact this Digital Reality makes on the generations being born into it:

- The way it completely changes their conceptualization and thought patterns,

- Their information acquisition mechanism,

- And the potentially skewed true-false determiners that get hard-wired into their brains. (Think of my son, who had difficulty believing the Grand Canyon was real because he’d seen so many life-like pictures of it before actually going there.)

How can we, as writers, capture and hang onto current and future consumers of our printed goods as these changes sweep over us? Many of my SS colleagues have taken first-steps along this path; I’ve read much of their work -- short stories and novels, both -- in electronic versions I bought online. But, is this enough? Are we thinking the right way? Or, are we victims caught in a pre-digital paradigm?

L.A. Noire, introduced in 2011, was the first video game to be shown at the Tribeca Film Festival, and it received accolades for its advanced storytelling.

According to Wikipedia: “L.A. Noire is set in Los Angeles in 1947 and challenges the player, controlling a Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officer, to solve a range of cases across five departments. Players must investigate crime scenes for clues, follow up leads, and interrogate suspects, and the players' success at these activities will impact how much of the cases' stories are revealed.

“The game draws heavily from both the plot and aesthetic elements of film noir, stylistic films made popular in the 1940s and 1950s that share similar visual styles and themes, including crime and moral ambiguity. The game uses a distinctive color palette, but in homage to film noir it includes the option to play the game in black and white. Various plot elements reference the major themes of gum-shoe detective and mobster stories such as Key Largo, Chinatown, The Untouchables, The Black Dahlia, and L.A. Confidential.”

What does this mean to us, as mystery writers?

And, I wonder: Is the next “True Classic” -- a modern work that will be experienced and studied down through the ages -- even now being keyed-in by some Shakespearian software writer working for a video game manufacturer?

The folks who ran Two Guns were intelligent, industrious, and worked hard to save their livelihoods. But, that didn’t keep them from being literally “kicked to the curb” by a new technology that they couldn't figure out how to deal with.

I’ve not made any suggestions for the best way we can position ourselves, as our way of thinking is swallowed whole by this new one. I can’t really come up with any. And, I know a lot of people have been contemplating, and still are contemplating, this problem.

But, Two Guns serves as a grim reminder: We need to figure it out SOON, or the signpost up ahead might well look like the one at that once-bustling Route 66 stop.

Labels:

Arizona,

Dixon Hill,

Los Angeles,

mysteries,

noir,

Route 66

31 May 2013

How 2 Big Sleeps Taught Me Magic

by Dixon Hill

When Last We Met . . .

Two weeks ago, I mentioned that I’d seen the “pre-release” of The Big Sleep.

Two weeks ago, I mentioned that I’d seen the “pre-release” of The Big Sleep.

The film classic The Big Sleep was released by Warner Brothers in August of 1946. However, an earlier, slightly different version of this same film was completed about a year before that. This earlier “pre-release” was granted limited distribution for USO use in the Pacific Theater as WWII wound down. Virtually no one would see it again, though, for over a half-century.

Warner sat on that original version of The Big Sleep because they wanted to unload a back-log of WWII films before they became passé, and because Lauren Bacall’s agent wanted to change elements of his client’s performance in The Big Sleep, in order to counter negative reviews she’d received in a recent film.

Thus: Warner re-edited the movie, including about 20 minutes of new footage shot during the film’s year-long hiatus, before releasing the final version -- which is the classic we all (or, at least, many of us) know and love. Meanwhile, that original “pre-release” version -- long believed lost -- was found, late in the 1990’s, sitting in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Almost immediately, funds were raised for restoration, and a re-release was planned for the “pre-release,” which finally came out on video in 2000.

Which is how I happened to stumble across it one night, on a DVD, when I myself was feeling a bit cross-eyed from lack of rest. And, how I realized that a comparison of the two films served to illustrate an important facet of writing for me.

The Not-So-Femme Fatal

In honor of the multi-layered-mystery element that (imho) helped propel The Big Sleep to greatness, I’ll begin my dissertation by invoking a different famous mystery film, which also starred Humphrey Bogart.

If memory serves me right: In The Maltese Falcon, while Peter Lorre’s character, Joel Cairo, is supposedly cooling his heels outside Sam Spade’s office door, Bogart (Spade) lifts Cairo’s card to his nose and sniffs. A humorous expression instantly explodes across Bogart’s face as he exclaims, “Gardenias!” He turns to his secretary and tells her, “Quick, darling, in with him!” (Or words to that effect.)

The way this scene is played out, a viewer is left with little question concerning Joel Cairo’s sexual preferences. Or, so it seems to me.

A similarly telling scene from the pre-release of The Big Sleep was cut from the 1946 version. At the same time, Marlowe’s search of Geiger’s bungalow -- where Carmen Sternwood (played by Martha Vickers) has been drugged and photographed -- is considerably shortened.

In commenting on my last post, David Edgerley Gates mentioned that the Hayes code (a sort of de facto censorship in operation at the time) made it necessary to change the film’s ending. He also helped explain why the changes in the Geiger bungalow scene were made, when he wrote: …[T]hey already had enough problems with the Martha Vickers character, trying to skirt the implication she was a nympho, not to mention a dope fiend.

I think David's very right. While the book makes it plain that Carmen is photographed in the nude, for instance, Martha Vickers is clothed in both versions of the film. All be it, she’s clothed in a Chinese-looking garment, which -- given social nuances then in vogue -- may have been construed as indicating her photo session involved sexual deviancy. But, there’s more sexual obfuscation than this going on.

After first reading this scene in the book, there was no question in my mind that Geiger was gay. Chandler’s description of Geiger’s bedroom clearly indicated its owner had a strong feminine side, at the very least. And, I’m pretty sure Chandler just about came right out and stated the fact when Marlowe described what the place felt like.

The final cut of the film, however, seems largely to gloss-over this idea. Though, I believe an argument could be made that love would be about the only motivation for Geiger’s assistant to go on his murderous rampage at Joe Brody’s apartment.

But, in the pre-release it’s a different story. After Marlowe finds the drugged Carmen Sternwood, he searches Geiger’s bungalow pretty thoroughly before he manages to discover the lockbox with Geiger’s sucker code. We even see where Marlowe finds the key to that box (a scene that I believe is missing from the final release). And, he goes to greater lengths, when it comes to covering up evidence that the girl had been in the bungalow.

During all this, we get a very good look at the feminine side of Geiger’s bedroom. The femininity is not overdone, but many of the book details do seem to be there. I believe this element, combined with the Chinese or Asian decorative influence, would have connoted the Geiger’s leanings fairly plainly to an audience of 1945. And, for anybody who somehow still missed the implications, the knowing smile on Bogart’s face, when he sniffs one of Geiger’s handkerchiefs, which he finds in that bedroom, would probably open the dimmest eyes.

Yet, almost none of this appears in the general release. Most of it wound up on the cutting room floor during final editing. And, while conforming with the Hayes code may well have played a part in deciding to make these cuts, I suspect another reasoning was also at work.

At first blush, Marlowe’s longer search made a lot of sense to me. To my way of thinking, mysteries are all too often replete with detectives who find what they’re searching for far too easily. So, it was refreshing to see Marlowe search for awhile before locating any valuable clues. Additionally, I remember thinking, “So THAT’S where it came from!” when he found the key to the lockbox, because the origin of this key had never seemed clear to me when watching the general release.

But, my excitement soon waned. I began to notice how long that search seemed to drag on. And, how such a lengthy search slowed the movie’s pace. Before long, I found myself changing my mind. I decided the editor had been wise to cut it -- even if the results left me puzzled about where Marlowe got that lockbox key.

A moment later, icy dread washed down through me.

I’d made similar mistakes in some of my own writing. Seeking to ensure verisimilitude, I’d been guilty of letting details stretch scenes too long. During rewrite, I’d noticed a resulting loss of tension, but my understanding of the mechanism involved was pretty sketchy. Watching this scene, however, and comparing it to the original film in mind, I was struck by a clear and concrete comprehension of the problem.

The solution, though, was still difficult to grasp. How to balance verisimilitude with the need to avoid slowing the action? Another difference between the two films would provide a key.

The Other Office

There’s a scene in the pre-release that I believe runs about five minutes, and I don’t think it’s in the ’46 release at all -- though there may be a short minute or two that was re-shot to condense it. The stuff that wound up on the cutting room floor was replaced with a new scene, in which Bogart and Bacall enjoy a bit of a tête-à-tête in a restaurant (left), helping to establish a romantic rapport that serves to support the re-edited ending.

There’s a scene in the pre-release that I believe runs about five minutes, and I don’t think it’s in the ’46 release at all -- though there may be a short minute or two that was re-shot to condense it. The stuff that wound up on the cutting room floor was replaced with a new scene, in which Bogart and Bacall enjoy a bit of a tête-à-tête in a restaurant (left), helping to establish a romantic rapport that serves to support the re-edited ending.

In the deleted scene (below) Marlowe meets with his cop buddy, the DA and some other guys, in the DA’s office. There, the PI has to explain why his actions, and letting him remain involved in the case (so he can continue to pursue those actions) would further the interests of justice, and the DA’s reelection. This scene was evidently intended to function as a thinly-veiled attempt to ensure that viewers understood the implications of what had transpired on-screen before it. This mid-film review, however, serves to bring the film’s brisk pace to a near screeching halt. And, it’s much worse than the lengthy search scene above, because there’s nothing new here; it’s all a rehash.

While I’m sure there are those who would appreciate this opportunity to gain a better understanding of the complicated double-or-triple-mystery unfolding before them: For me, the confusion created by unexpected occurrences within the film, is exactly what sucks me into the vortex of the plot’s wildly spinning fabric. In my view, this “review” scene provides such a vast breath of calm, still air, the film’s whirling vortex shatters against it, dissipating. Wildly careening plot elements flutter free and drift down to flop dead upon the ground.

Eventually, I came to see this scene as being somewhat akin to a magician stopping mid-act to say, “Okay. Now see, this is what I’ve really been doing.” When a magician reveals the slight of hand behind the trick, all the magic goes out of the thing. It dies.

Which is why I’m glad I saw this, because there's enough dead writing in this world; I don't need to kill more of it. But, I’m a guy who drives himself nearly crazy, ensuring that ta reader can understand why my characters are motivated to do what they’re doing, because I don’t want folks getting lost, or tossing down a book or story because they think I’ve got a character doing something s/he wouldn’t. On the other hand, I also know it’s important to keep a reader in the dark sometimes, and this why I found this scene so useful.

It serves as a clear reminder that the line between what I can tell and what I have to keep up my sleeve is clearly demarcated by the question, “Will knowing this shatter the magic?” At the same time, I realized this was also the answer to the question: How to balance verisimilitude with the need to avoid slowing the action?

The answer -- for me, at least -- is to keep my eye on the magic. If the magic thrives throughout the action, it’s fine. If it dies, or even just dies-down, I know it’s time to cut.

The trick in both cases is: Keep my eye on the magic. This phrase might not seem terribly concrete to you. Or, perhaps you’re not the sort of writer who needs to bear it in mind. But, for me: The simplicity of that phrase is something my mind can grasp and hang onto deeply. It’s a tool I can carry with me anywhere I go

Keep your eye on the magic! That’s what I learned from watching two versions of The Big Sleep..

See you in two weeks,

--Dixon

Two weeks ago, I mentioned that I’d seen the “pre-release” of The Big Sleep.

Two weeks ago, I mentioned that I’d seen the “pre-release” of The Big Sleep.The film classic The Big Sleep was released by Warner Brothers in August of 1946. However, an earlier, slightly different version of this same film was completed about a year before that. This earlier “pre-release” was granted limited distribution for USO use in the Pacific Theater as WWII wound down. Virtually no one would see it again, though, for over a half-century.

Warner sat on that original version of The Big Sleep because they wanted to unload a back-log of WWII films before they became passé, and because Lauren Bacall’s agent wanted to change elements of his client’s performance in The Big Sleep, in order to counter negative reviews she’d received in a recent film.

Thus: Warner re-edited the movie, including about 20 minutes of new footage shot during the film’s year-long hiatus, before releasing the final version -- which is the classic we all (or, at least, many of us) know and love. Meanwhile, that original “pre-release” version -- long believed lost -- was found, late in the 1990’s, sitting in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Almost immediately, funds were raised for restoration, and a re-release was planned for the “pre-release,” which finally came out on video in 2000.

Which is how I happened to stumble across it one night, on a DVD, when I myself was feeling a bit cross-eyed from lack of rest. And, how I realized that a comparison of the two films served to illustrate an important facet of writing for me.

The Not-So-Femme Fatal

In honor of the multi-layered-mystery element that (imho) helped propel The Big Sleep to greatness, I’ll begin my dissertation by invoking a different famous mystery film, which also starred Humphrey Bogart.

If memory serves me right: In The Maltese Falcon, while Peter Lorre’s character, Joel Cairo, is supposedly cooling his heels outside Sam Spade’s office door, Bogart (Spade) lifts Cairo’s card to his nose and sniffs. A humorous expression instantly explodes across Bogart’s face as he exclaims, “Gardenias!” He turns to his secretary and tells her, “Quick, darling, in with him!” (Or words to that effect.)

The way this scene is played out, a viewer is left with little question concerning Joel Cairo’s sexual preferences. Or, so it seems to me.

A similarly telling scene from the pre-release of The Big Sleep was cut from the 1946 version. At the same time, Marlowe’s search of Geiger’s bungalow -- where Carmen Sternwood (played by Martha Vickers) has been drugged and photographed -- is considerably shortened.

In commenting on my last post, David Edgerley Gates mentioned that the Hayes code (a sort of de facto censorship in operation at the time) made it necessary to change the film’s ending. He also helped explain why the changes in the Geiger bungalow scene were made, when he wrote: …[T]hey already had enough problems with the Martha Vickers character, trying to skirt the implication she was a nympho, not to mention a dope fiend.

I think David's very right. While the book makes it plain that Carmen is photographed in the nude, for instance, Martha Vickers is clothed in both versions of the film. All be it, she’s clothed in a Chinese-looking garment, which -- given social nuances then in vogue -- may have been construed as indicating her photo session involved sexual deviancy. But, there’s more sexual obfuscation than this going on.

After first reading this scene in the book, there was no question in my mind that Geiger was gay. Chandler’s description of Geiger’s bedroom clearly indicated its owner had a strong feminine side, at the very least. And, I’m pretty sure Chandler just about came right out and stated the fact when Marlowe described what the place felt like.

The final cut of the film, however, seems largely to gloss-over this idea. Though, I believe an argument could be made that love would be about the only motivation for Geiger’s assistant to go on his murderous rampage at Joe Brody’s apartment.

But, in the pre-release it’s a different story. After Marlowe finds the drugged Carmen Sternwood, he searches Geiger’s bungalow pretty thoroughly before he manages to discover the lockbox with Geiger’s sucker code. We even see where Marlowe finds the key to that box (a scene that I believe is missing from the final release). And, he goes to greater lengths, when it comes to covering up evidence that the girl had been in the bungalow.

During all this, we get a very good look at the feminine side of Geiger’s bedroom. The femininity is not overdone, but many of the book details do seem to be there. I believe this element, combined with the Chinese or Asian decorative influence, would have connoted the Geiger’s leanings fairly plainly to an audience of 1945. And, for anybody who somehow still missed the implications, the knowing smile on Bogart’s face, when he sniffs one of Geiger’s handkerchiefs, which he finds in that bedroom, would probably open the dimmest eyes.

Yet, almost none of this appears in the general release. Most of it wound up on the cutting room floor during final editing. And, while conforming with the Hayes code may well have played a part in deciding to make these cuts, I suspect another reasoning was also at work.

At first blush, Marlowe’s longer search made a lot of sense to me. To my way of thinking, mysteries are all too often replete with detectives who find what they’re searching for far too easily. So, it was refreshing to see Marlowe search for awhile before locating any valuable clues. Additionally, I remember thinking, “So THAT’S where it came from!” when he found the key to the lockbox, because the origin of this key had never seemed clear to me when watching the general release.

But, my excitement soon waned. I began to notice how long that search seemed to drag on. And, how such a lengthy search slowed the movie’s pace. Before long, I found myself changing my mind. I decided the editor had been wise to cut it -- even if the results left me puzzled about where Marlowe got that lockbox key.

A moment later, icy dread washed down through me.

I’d made similar mistakes in some of my own writing. Seeking to ensure verisimilitude, I’d been guilty of letting details stretch scenes too long. During rewrite, I’d noticed a resulting loss of tension, but my understanding of the mechanism involved was pretty sketchy. Watching this scene, however, and comparing it to the original film in mind, I was struck by a clear and concrete comprehension of the problem.

The solution, though, was still difficult to grasp. How to balance verisimilitude with the need to avoid slowing the action? Another difference between the two films would provide a key.

The Other Office

There’s a scene in the pre-release that I believe runs about five minutes, and I don’t think it’s in the ’46 release at all -- though there may be a short minute or two that was re-shot to condense it. The stuff that wound up on the cutting room floor was replaced with a new scene, in which Bogart and Bacall enjoy a bit of a tête-à-tête in a restaurant (left), helping to establish a romantic rapport that serves to support the re-edited ending.

There’s a scene in the pre-release that I believe runs about five minutes, and I don’t think it’s in the ’46 release at all -- though there may be a short minute or two that was re-shot to condense it. The stuff that wound up on the cutting room floor was replaced with a new scene, in which Bogart and Bacall enjoy a bit of a tête-à-tête in a restaurant (left), helping to establish a romantic rapport that serves to support the re-edited ending.In the deleted scene (below) Marlowe meets with his cop buddy, the DA and some other guys, in the DA’s office. There, the PI has to explain why his actions, and letting him remain involved in the case (so he can continue to pursue those actions) would further the interests of justice, and the DA’s reelection. This scene was evidently intended to function as a thinly-veiled attempt to ensure that viewers understood the implications of what had transpired on-screen before it. This mid-film review, however, serves to bring the film’s brisk pace to a near screeching halt. And, it’s much worse than the lengthy search scene above, because there’s nothing new here; it’s all a rehash.

While I’m sure there are those who would appreciate this opportunity to gain a better understanding of the complicated double-or-triple-mystery unfolding before them: For me, the confusion created by unexpected occurrences within the film, is exactly what sucks me into the vortex of the plot’s wildly spinning fabric. In my view, this “review” scene provides such a vast breath of calm, still air, the film’s whirling vortex shatters against it, dissipating. Wildly careening plot elements flutter free and drift down to flop dead upon the ground.

Eventually, I came to see this scene as being somewhat akin to a magician stopping mid-act to say, “Okay. Now see, this is what I’ve really been doing.” When a magician reveals the slight of hand behind the trick, all the magic goes out of the thing. It dies.

Which is why I’m glad I saw this, because there's enough dead writing in this world; I don't need to kill more of it. But, I’m a guy who drives himself nearly crazy, ensuring that ta reader can understand why my characters are motivated to do what they’re doing, because I don’t want folks getting lost, or tossing down a book or story because they think I’ve got a character doing something s/he wouldn’t. On the other hand, I also know it’s important to keep a reader in the dark sometimes, and this why I found this scene so useful.

It serves as a clear reminder that the line between what I can tell and what I have to keep up my sleeve is clearly demarcated by the question, “Will knowing this shatter the magic?” At the same time, I realized this was also the answer to the question: How to balance verisimilitude with the need to avoid slowing the action?

The answer -- for me, at least -- is to keep my eye on the magic. If the magic thrives throughout the action, it’s fine. If it dies, or even just dies-down, I know it’s time to cut.

The trick in both cases is: Keep my eye on the magic. This phrase might not seem terribly concrete to you. Or, perhaps you’re not the sort of writer who needs to bear it in mind. But, for me: The simplicity of that phrase is something my mind can grasp and hang onto deeply. It’s a tool I can carry with me anywhere I go

Keep your eye on the magic! That’s what I learned from watching two versions of The Big Sleep..

See you in two weeks,

--Dixon

19 April 2013

A True Story of Crooks and Spies

by Dixon Hill

Lisbon in War Time

The thriller writer John Masterman, who was also an Oxford history don, sportsman, and the chairman of the WWII British intelligence unit known as “Twenty Committee,” described war-time Lisbon as a “sort of international clearing ground, a busy ant heap of spies and agents, where political and military secrets and information -- true and false, but mainly false -- were bought and sold and where men’s brains were pitted against each other.”

|

| Sir John Cecil Masterman |

As soon as he removed his parachute, in his native Britain, however, he walked to the nearest phone and turned himself in to MI5, volunteering to spy for England instead.

For months afterward, Zigzag had radioed his Abwehr masters whatever MI5 told him to. The master illusionist Jasper Maskelyne was even brought in. Working with his team, Maskelyne created a ruse that would dupe the Germans into believing Zigzag (“Agent Fritz” to the Germans) had destroyed the transformers providing electricity to the De Havilland aircraft factory that produced Mosquito bombers in England, putting the factory out of action for some time.

Everything had gone very well in England; the factory bombing ruse had worked so well, the Nazis even presented “Agent Fritz” with the Iron Cross. Then -- his German assignment complete -- Zigzag sent a message that indicated he was under suspicion and had decided to escape back to Germany. MI5 duly packed him off to meet a prearranged contact with the Abwehr in Lisbon, in order to begin spying for Britain within the occupied continent itself.

Now, however, reports reaching MI5 and MI6 indicated Zigzag had gone rogue. Having contacted his Nazi masters in Lisbon, as planned, he’d then ditched the British plan, instead obtaining high-explosive charges disguised as lumps of coal, which he volunteered to plant in the coal bunkers of the “City of Lancaster,” in order to sink the steamer that had transported him from Liverpool to Lisbon, and which carried supplies important for the British army in North Africa.

MI6 put a man on Zigzag’s tail, planning to kill the double agent if needed, in order to save the ship with its critical supplies, while MI5 scrambled to get one of Zigzag’s controllers on the ground in Lisbon to find out what was going on.

The stuff of fiction. Except that this is NON-fiction!

Breaking the Code

|

| Ben Macintyre |

Before the war, a low-born English villager named Edward Arnold “Eddie” Chapman was a thief, con artist and philanderer who managed to charm nearly everyone he met. During the war, he was recruited to work as a spy for the Abwehr, the Nazi intelligence apparatus. But, due to his nature – and the fruits of code breaking – he was doubled-back against the Germans as the British operative “Agent Zigzag.”

A Little Background

During WWII, the Nazis encrypted their radio traffic using cipher gear known as the Enigma Machine. Essentially, cipher clerks would type a plain-text message into the Enigma Machine, and an enciphered text printed out the other end in 7-figure blocks, which were then forwarded to radio operators for transmission.

Enigma machines were sent to all major commands, and even stationed aboard U-boats and other naval vessels. This was because the Nazis felt their Enigma machine rendered all encrypted messages “unbreakable,” and they wanted secure communications throughout the Third Reich.

However, Arthur Owens (Britain’s “Agent Snow”) managed to obtain one of the machines (or parts of it, depending on which account you read), along with a book of codes and signal operating instructions, for British intelligence. This gave the cryptographers and other brilliant professors working at Bletchley Park, England – also called “Station X” – a sort of running jump. And they managed to break the Nazi’s unbreakable cipher system quite early in the war, enabling the Brits to read the Nazi’s most classified radio signals from then on.

They called this secret ULTRA.

But, the Brits weren’t just using ULTRA to gather Wehrmacht troop deployment information. They were also reading all the secret transmissions sent out by the Abwehr – including transmissions that identified Nazi spies. Using this information, the intelligence services were able to capture most Nazi spies as (or soon after) they entered the country. Then, in a remarkable feat of ingenuity, they managed to “turn” a significant number of these spies, using them to transmit bogus intelligence reports back to the Abwehr.

The specific information those turncoat spies delivered was carefully considered and vetted by a committee formed from representatives from all branches of the military, the Home Office and industry, chaired by the eminent Oxford don John Masterman, mentioned at the beginning of this article.

This committee, charged with generating the information that would double-cross Germany’s spy masters, without giving the game away, was named XX, representing “double-cross”, and in that ineffable British humor, the name finally became “Twenty Committee” as a pun on the Roman numeral XX. Twenty Committee worked hand-in-glove with MI5 (using ULTRA intercepts) to identify, then turn, numerous agents throughout the war.

In February of 1942, these spy hunters began to intercept transmissions about a new spy codenamed “Fritz” who would be coming to England soon. But, while most of the spies the Brits caught seemed fairly inept, and none of them were native British sons, this one looked to be different.

ZIG

During the 1930’s, Eddie Chapman, and some of the nefarious friends he hung around posh London clubs with, learned to use Gelignite to blow open safes. ( I told you it sounds like fiction!)

The “Jelly Gang,” as they were quickly dubbed, realized they’d discovered a fantastic new way to nab stacks of quick cash. The gang blew a lot of safes -- and a lot of stolen money, in those posh London clubs. But, by February of ’39 the cops were closing in on the Jelly Gang, so they decided to evade pursuit by taking a vacation with Chapman’s girlfriend on the Channel island of Jersey.

|

| Eddie Chapman, a man of many names |

Though he broke into homes and businesses to obtain cash and clothing, planning to get his hands on a boat and escape from the island back to London, Chapman’s freedom was short-lived. On March 11, 1939, the Royal Court of Jersey sentenced Eddie Chapman to two years hard labor for housebreaking and larceny -- which wound up being an incredibly lucky break for the guy!

ZAG

The other members of the Jelly Gang had been arrested in their hotel rooms on the island, and were taken back to London, where they stood trial and got forty years for their safe cracking exploits.

But, because Eddie had committed crimes on Jersey, while on the lamb, the island authorities refused to let him be taken back to London before serving out his two year sentence on Jersey. This sentence was increased, somewhat, after Chapman escaped from the prison but was again arrested before managing to escape the small Channel island.

During Chapman’s incarceration, Hitler invaded Poland and Britain went to war. Before his release, the Nazi army invaded the small Channel isle of Jersey, which they occupied for much of the rest of the war. This made little difference to the inmates, except that the food went down hill.

Upon his release, Chapman found it impossible to leave the occupied island, so he and a buddy opened a small shop. Chapman had met this friend, Anthony Charles Faramous, when he had been thrown in the island pokey for a fairly minor infraction, and the two shared a cell.

Faramous knew a little about cutting hair, so he ran a barber shop in the front of the store, while Chapman dealt in the black market out the back. The two men longed to get back to London, but couldn’t find a way. Until Chapman suggested they volunteer to spy on England for the Nazis.

Their initial offer was met with a lackluster response. But, several months later -- after the men had been shipped off to a French concentration camp -- Chapman was interviewed and recruited by the Nazis, who gave him a 3-month mission of intelligence collection and sabotage in England, while they hung onto Faramous as a hostage.

Before it was all over, Eddie Chapman would gather intelligence and bed beauties across Occupied France, Germany, Norway and England. But was he really a German spy who tried to sink a merchant vessel laden with critical British war cargo?

I’m not about to ruin things by telling you. If you want the details, you’ll have to read the book.

|

| Lord Victor Rothschild, inspiration for "Q" |

In two weeks, I’ll be back to review another terrific espionage book -- a fiction novel with a story that sprawls from the closing days of WWII, to concentrate and finally conclude in Cold War Berlin. This novel, entitled Black Traffic, was written by our own David Edgerley Gates, whose prose style (imho) sings only the best notes of John le Carré and W.E.B. Griffin, combining to form a written concerto of suspense that kept me up nights until I was done.

See you then!

--Dix

22 March 2013

Theory on the Origin of the Muse

by Dixon Hill

(or: Character/Idea Generation Eccentricities Pt. II)

Prologue:

About five weeks ago, Louis Willis posted an article concerning character development and the impact it has on a writer’s sanity. In the Comments section of that post, I cited earlier comments made by Fran, Elizabeth and R.T., and explained that my system of character creation/development was sort of a “rough hybrid” of certain ideas they had espoused.

Inspired by Louis’ post, I wrote my own post (2 weeks ago), in which I explained how I sometimes incorporate daydreaming and play into my methodology for character development. This post partially clarified what I meant in my own comments on Louis’ post. And, I mentioned something Fran had written, in her comments about Louis’s post, to hopefully help facilitate my explanation.

Today, I will expand that explanation by noting how some comments made by Elizabeth illustrate ideas that sometimes figure into the “primordial stew” of my character development. Additionally, I’d like to touch on the importance of “non-daydream dreaming” -- as I believe it factors into the equation.

(I’d like to take a moment to make it clear, here, that: Though I might quote Fran, Elizabeth or RT in order to use their quotes as springboards for my own ideas, they are just (and ONLY) that -- Springboards. You should not think I am speaking for them. I can only speak for myself, in this realm, and would not want anyone to think I’m trying to convey what Fran, Elizabeth or RT may actually believe concerning the subject at hand. Such clarification, I would leave up to them.

Further: This series of essays concerns the manner in which I have sometimes created characters and/or plot in my own successful writing. The reader, however, should not construe this as meaning that I believe the methods outlined are the “right ones” or the “only methods” that a writer may use. Instead, my objective is merely to share methods I have used in the past -- for those who may have an interest in such techniques – and to possibly theorize about the psychological origins of these methods, as well as their possible link to the origin of the Greek term “Muse.”)

That Being Said . . .

Elizabeth wrote, in her comment on Louis’s article about character creation: "...the character starts talking in my head. I simply write down what he or she says..."

This sometimes happens to me, too. And, I always think I’m really lucky when it does. Because, a character who starts talking in my head usually has a humdinger of a story to tell, and s/he tells it very forcefully.

In my opinion, such “character force” really adds punch to writing -- even in the first draft. A character like that is often angry, hurt and bursting with story. You cut ‘em, man, and they just spill their guts all over the place. It spews out hot and strong; they’re not shy. And, what they say will cut a reader to the emotional quick. Very powerful stuff.

What is this voice?

Well, the voice is my imagination, of course. But, in a very important way, it’s more than that, because -- while each voice is inarguably a part of me, generated by my own imagination -- it also stands apart from me, extremely alien to the thoughts that had, moments ago, been dominating my conscious mind.

This sort of voice is what I often think the ancient poets were speaking of, when they coined the term “muse,” perhaps because it seemed as if the gods must have injected the thought -- wholly unexpected by the thinker -- straight into the thinker’s mind.

My belief, however, is that these voices in my head are generated by my subconscious. I suspect that the reason I’m often startled by them, and surprised when they speak out in my mind, is because they’re created when a subconscious thought bubbles up into my conscious mind.

Vast areas of the human brain and intellect remain uncharted. In many cases, we currently don’t even have an inkling of what questions we should be asking -- concerning thought, the mind, or the brain -- in order to get the answers we would need, if we are to increase our knowledge in this realm.

One thing I believe most researchers agree on, however, is: Among other tasks, our “subconscious” is that portion of our thinking which generates dreams. And, our dreams (mine, at least -- and I assume yours also) are populated by people and creatures that are not silent. They speak to us. In some cases, even when they don’t use words, their body language and facial expressions leave us feeling that they desperately desire to communicate some intangible idea to us. This can sometimes be an idea we (our dreaming selves) intuit as having great importance of some kind.

I often find that the “voice” comes when I’m looking at something that ignites my interest. A few seconds or minutes later, as I’m concentrating on that visual “igniter” (or catalyst), a voice suddenly, and surprisingly speaks out in my head. Conversely, on rarer instances, when I’m listening intently to some auditory catalyst, an unexpected image (or “vision”) will suddenly explode across my mind’s eye.

I believe the intersect between the conscious mind and the subconscious is one of those largely-uncharted areas I discussed a few paragraphs earlier. And, the theory I would postulate (I know of absolutely no scientific evidence to support this theory, I might warn you!) is that, when the subconscious tries to communicate with our conscious brain, it does so through it’s dream-generation mechanism.

When I’m looking at a visual catalyst, my eyes and the visual centers of my brain are already fully engaged, so I hear a voice -- the auditory portion of a dream (according to my theory) that’s generated by my subconscious, and communicated to my conscious mind through that portion it can access: a sort of “bridge to conscious thought,” if you will. Likewise, when my auditory senses are already engaged by a catalyst, I receive the visual portion of a waking dream, because my visual senses are not engaged, leaving that pathway open to my subconscious’ intrusion on my thoughts.

In other words, I believe these “voices” and “visions” are the result of my subconscious using dream-mechanism-stimulation to communicate with my waking mind, along pathways that are not (at that moment) tied-up in the reception of catalytic stimulus.

This is why I say that the voice I sometimes hear is created “when a subconscious thought bubbles up into my conscious mind.” Additionally: I believe, this is why -- while the thought obviously comes from my own mind -- it also seems alien, and apart from me. Who has never encountered a disturbingly alien landscape in a dream? When the audio or visual portion of a dream suddenly intrudes on one’s waking mind, that can be just as disturbingly alien in nature.

What can act as a catalyst for these voices?

For me, at least, that varies greatly.

The protagonist’s voice in my short story “Dancing in Mozambique” (Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, July 2010), for instance, first spoke to me when I sat looking at a “Mysterious Photograph” in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine.

For those unaware: AHMM runs that Mysterious Photograph page as a contest, asking for short-shorts around 250 words, and they publish the winning entry a few months later. The photo in that month’s issue showed a staircase in what seemed, to me at least, to be a haunted house, or a spooky old tumble-down hotel.

I looked at the photo, and suddenly heard a gravelly voiced man in my mind say: “When a pineapple came bouncing down the steps of that spook house staircase, I knew we’d found Jai. He’d seen us coming.” The voice had a rough, haunting and “hunted” edge to it that spoke of exhaustion after long foot-slogging and prolonged bombardment of adrenalin. It wasn’t a voice I’d ever heard before, but I instantly knew the man behind it.

I knew him, because I’d known a lot of men like that. I’d met them while I was in the army. At times, in fact, I’d been that man. My subconscious knew him inside and out, which (I believe) is why -- though I didn’t recognize the voice, itself -- I KNEW that man! And, knew him WELL.

As I am wont to do, I let the voice continue its tale as I typed the words into my computer. This is similar to what’s often called “stream of consciousness” writing, though, in a case like this one, based on the theory I postulated earlier, I would tend to deem it a “stream of subconscious.”

First, the man told me what happened immediately after that grenade (“pineapple”) had been tossed down a dilapidated staircase at him.

Later, I listened as he told me what had happened to him previously, how he had come to find himself in this dark place.

I knew, when I met his voice, that the man was a soldier. But, I didn’t know what kind of soldier. Over time, as he told me his story, I realized that he’d spent many years working as a mercenary in Africa.

At that point, I remembered an old adage I’d once learned. This adage, a sort of short limerick, or “mantra,” is a mnemonic device designed to explain (and help people remember) how to ensure that a person who is shot does not survive the wounds. It is a method named, I believe, for the place where the technique was born: “The Mozambique*.” And, I knew then that I’d discovered the axle around which my story’s helix could be entwined, as well as the name of the tumble-down hotel in which the action took place.

After the voice in my head finished speaking, I went back through what I’d written -- cognizant of the Mozambique axle I wanted running through the center of the story -- and put down the lines that fit into 250 words, yet still strongly told the man’s story.

The 250-word version of the story was probably not terribly good. I don’t love it, because, to my way of thinking, it is a skeleton. And, though there is suspense, there is little mystery -- particularly at this length. It certainly didn’t win the Mysterious Photo contest, either. But, I wrote it more as an exercise in teaching myself to write shorter, than as an attempt to win a contest. [As readers of my posts on SS may know, I’m not somebody who has been successful with short-shorts. In fact, the shortest story I’ve written, that sold, was submitted at 1,500 words (to a magazine that wanted 1,000 to 1,500 word fiction), but later -- after I cut it further, at the editor’s request -- finally ran just under 1,000 words. And, serendipitously, that story "Buffalo Smoke" came out in this month's (April 2013) issue of Boy's Life.]

The initial (250-word) version of “Dancing in Mozambique” is posted below, so you can see the results of the above process. As I wrote earlier: I don’t love it. The voice in my head is still there, however, for you to “hear” as you read it.

Readers who wish to do so, and who have access to the July 2010 issue of EQMM, may read the final product for comparison and contrast -- which may prove interesting, particularly in light of my next post.

Dancing in Mozambique

(250-word version)

The Hotel Mozambique, Chicago. Aptly named, I thought.

When a pineapple came bouncing down the steps of that spook house staircase, I knew we’d found Jai. He’d seen us coming.

Jai was a tricky bastard—learned that the day I met him. We fought as mercs in Africa. His last trick was stealing our pay, leaving us to die.

But Claw and I survived.

Now the pineapple. We dove right and left; as effective as hiding behind a sheet of paper. The grenade hit bottom, but didn’t go off.

Claw shouted, “Dud!” scrambled up the stairs, feet pounding on the hollow, rotted wood. I saw the pin still in the grenade; Jai always was a tricky bastard.

I started to shout. My warning died stillborn, executed by a heavy-caliber double-tap from above. The slugs kicked Claw’s body half-way down the stairs.

Blue smoke curled down the staircase. A step groaned.

I side stepped, saw a jeans-covered hip between rail and ceiling. I fired; blood geysered and Jai fell, weapon bumping down the steps. I vaulted Claw’s body and rounded the landing, pumped a round into Jai’s torso—center mass—as he struggled to pull his backup piece. My third shot drilled his head.

I walked away, recalling that long-ago training mantra learned in Africa, when I still called him friend, before he betrayed us: “Twice in the body, once in the head; that’s the way you know he’s dead—when you dance in Mozambique.”

I shut the door behind me.

In two weeks, I will explain how R.T.’s comments on Louis Willis’ post (the one that set all this in motion) illustrate the manner in which characters organically changed, in order to add depth and life to the piece, fleshing-out the 250-word skeleton into the final story of nearly 8,000 words, which sold to EQMM. This explanation, however, will necessarily evolve from a discussion of “character creation” into a discussion of how character action and interaction sometimes blossom naturally into organic plot. Which is why I’ll save it for next time.

See you in two weeks! --Dix

*Please note: Though I learned of the “Mozambique” during my tenure in the army, neither the Mozambique technique, nor the limerick that accompanies it, are taught in any US Army schools, nor is the technique considered acceptable practice.

|

| Terpsichore (a muse), marble, John Walsh 1771 |

Prologue:

About five weeks ago, Louis Willis posted an article concerning character development and the impact it has on a writer’s sanity. In the Comments section of that post, I cited earlier comments made by Fran, Elizabeth and R.T., and explained that my system of character creation/development was sort of a “rough hybrid” of certain ideas they had espoused.

Inspired by Louis’ post, I wrote my own post (2 weeks ago), in which I explained how I sometimes incorporate daydreaming and play into my methodology for character development. This post partially clarified what I meant in my own comments on Louis’ post. And, I mentioned something Fran had written, in her comments about Louis’s post, to hopefully help facilitate my explanation.

Today, I will expand that explanation by noting how some comments made by Elizabeth illustrate ideas that sometimes figure into the “primordial stew” of my character development. Additionally, I’d like to touch on the importance of “non-daydream dreaming” -- as I believe it factors into the equation.

(I’d like to take a moment to make it clear, here, that: Though I might quote Fran, Elizabeth or RT in order to use their quotes as springboards for my own ideas, they are just (and ONLY) that -- Springboards. You should not think I am speaking for them. I can only speak for myself, in this realm, and would not want anyone to think I’m trying to convey what Fran, Elizabeth or RT may actually believe concerning the subject at hand. Such clarification, I would leave up to them.

Further: This series of essays concerns the manner in which I have sometimes created characters and/or plot in my own successful writing. The reader, however, should not construe this as meaning that I believe the methods outlined are the “right ones” or the “only methods” that a writer may use. Instead, my objective is merely to share methods I have used in the past -- for those who may have an interest in such techniques – and to possibly theorize about the psychological origins of these methods, as well as their possible link to the origin of the Greek term “Muse.”)

That Being Said . . .

Elizabeth wrote, in her comment on Louis’s article about character creation: "...the character starts talking in my head. I simply write down what he or she says..."

This sometimes happens to me, too. And, I always think I’m really lucky when it does. Because, a character who starts talking in my head usually has a humdinger of a story to tell, and s/he tells it very forcefully.

In my opinion, such “character force” really adds punch to writing -- even in the first draft. A character like that is often angry, hurt and bursting with story. You cut ‘em, man, and they just spill their guts all over the place. It spews out hot and strong; they’re not shy. And, what they say will cut a reader to the emotional quick. Very powerful stuff.

What is this voice?

Well, the voice is my imagination, of course. But, in a very important way, it’s more than that, because -- while each voice is inarguably a part of me, generated by my own imagination -- it also stands apart from me, extremely alien to the thoughts that had, moments ago, been dominating my conscious mind.

This sort of voice is what I often think the ancient poets were speaking of, when they coined the term “muse,” perhaps because it seemed as if the gods must have injected the thought -- wholly unexpected by the thinker -- straight into the thinker’s mind.

My belief, however, is that these voices in my head are generated by my subconscious. I suspect that the reason I’m often startled by them, and surprised when they speak out in my mind, is because they’re created when a subconscious thought bubbles up into my conscious mind.

|

| "Three Sphinxes of Bikini" Salvador Dali |

One thing I believe most researchers agree on, however, is: Among other tasks, our “subconscious” is that portion of our thinking which generates dreams. And, our dreams (mine, at least -- and I assume yours also) are populated by people and creatures that are not silent. They speak to us. In some cases, even when they don’t use words, their body language and facial expressions leave us feeling that they desperately desire to communicate some intangible idea to us. This can sometimes be an idea we (our dreaming selves) intuit as having great importance of some kind.