I mentioned last post that I was teaching classes

on the mystery from novel to film, and listed the books and

movies I'd be teaching. Rob Lopresti had done a little research

on my first author, John Buchan, creator of "The Thirty-Nine

Steps," and sent me his blog on him, which was quite

interesting.

Buchan was a Scot, which might have had something to do with his grand descriptions of the Scottish countryside in "The 39 Steps," and began his adult life with a brief legal career, which he gave up for his real passion -- writing. On October 19, 1915, John Buchan's first novel, "The Thirty-nine Steps" was published and was an immediate hit, selling 25,000 copies by the end of the year. It tells the story of Richard Hannay, a South African visiting London who gets caught up in an espionage ring. Jason Worden argued that Buchan actually invented a new sub-genre: the story in which a civilian gets chased both by the bad guys, and by the police who think he is the bad guy. That paranoia made it perfect for Alfred Hitchcock, who not only filmed "The Thirty-nine Steps," but used a similar plot in two other movies. Buchan wrote many more novels, including four about the plucky Richard Hannay. During World War I, his penchant for writing came in handy as he wrote propaganda for the British government. He also served as Governor General of Canada until his death in 1940. As Rob said, not bad for a thriller writer.

Buchan was a Scot, which might have had something to do with his grand descriptions of the Scottish countryside in "The 39 Steps," and began his adult life with a brief legal career, which he gave up for his real passion -- writing. On October 19, 1915, John Buchan's first novel, "The Thirty-nine Steps" was published and was an immediate hit, selling 25,000 copies by the end of the year. It tells the story of Richard Hannay, a South African visiting London who gets caught up in an espionage ring. Jason Worden argued that Buchan actually invented a new sub-genre: the story in which a civilian gets chased both by the bad guys, and by the police who think he is the bad guy. That paranoia made it perfect for Alfred Hitchcock, who not only filmed "The Thirty-nine Steps," but used a similar plot in two other movies. Buchan wrote many more novels, including four about the plucky Richard Hannay. During World War I, his penchant for writing came in handy as he wrote propaganda for the British government. He also served as Governor General of Canada until his death in 1940. As Rob said, not bad for a thriller writer.

Learning all this about John Buchan made me want

to learn more about the other writers I was featuring in my class.

Although John Buchan was the least known (to me anyway) of the four,

I decided to delve a little deeper into the others. I knew

before hand -- from general knowledge and reading Lillian Hellman's

wonderful book "Pentimento" -- that Dashiel Hammett had

worked as a detective for the Pinkerton agency, was an alcoholic, and

had issues with rejection -- at least according to Ms. Hellman.

Delving a little deeper, I learned that Samuel Dashiel Hammett worked

for the Pinkertons from 1915 to 1922, quitting due to the Pinkertons

penchant for strike breaking. Almost all of his books and short

stories were written in the 1920s and '30s, due in part to his bad

health and his interest in political activism. He joined The Civil

Rights Congress (the CRC), a leftist organization, and soon became

their president. The CRC came under scrutiny in the late 1940s, and

Hammett was subpoenaed to appear before a judge to name a list of

contributors to a defense fund set up by the CRC for people accused

of communist sympathies. He refused, citing the fifth amendment, and

was sent to federal prison. Only a few years later, in the early

1950s, he was blacklisted by the HUAC and was unable to work as a

writer from that point until his death in 1961. Raymond Chandler

wrote in The Simple Art of Murder, “Hammett was the ace

performer... He is said to have lacked heart; yet the story he

himself thought the most of, The Glass Key, is the record of a

man's devotion to a friend. He was spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he

did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at

all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

And speaking of Raymond Chandler, one of my all

time favorite writers, I was interested to learn that he didn't start

writing until 1932 at the age of forty-four. A former oil company

executive, he lost his job during the Great Depression and decided to

take up writing. In a letter to his London publisher, Hamish

Hamiton, Chandler explained why he began reading and eventually

writing for pulp magazines: “Wandering up and down the Pacific

Coast in an automobile I began to read pulp magazines, because they

were cheap enough to throw away and because I never had at any time

any taste for the kind of thing which is known as women's magazines.

This was in the great days of the Black Mask (if I may call

them great days) and it struck me that some of the writing was pretty

forceful and honest, even though it had its crude aspect. I decided

that this might be a good way to try to learn to write fiction and

get paid a small amount of money at the same time. I spent five

months over an 18,000 word novelette and sold it for $180. After that

I never looked back, although I had a good many uneasy periods

looking forward.”

In the introduction to Trouble Is My Business

(1950), a collection of four of his short stories, Chandler wrote,

“The emotional basis of the standard detective story was and had

always been that murder will out and justice will be done. Its

technical basis was the relative insignificance of everything except

the final denouement. What led up to that was more or less passage

work. The denouement would justify everything. The technical basis of

the Black Mask type of story on the other hand was that the

scene outranked the plot, in the sense that a good plot was one which

made good scenes. The ideal mystery was one you would read if the end

was missing. We who tried to write it had the same point of view as

the film makers. When I first went to Hollywood a very intelligent

producer told me that you couldn't make a successful motion picture

from a mystery story, because the whole point was a disclosure that

took a few seconds of screen time while the audience was reaching for

its hat. He was wrong, but only because he was thinking of the wrong

kind of mystery.”

Chandler also described the struggle that the

writers of pulp fiction had in following the formula demanded by the

editors of the pulp magazines: “As I look back on my stories it

would be absurd if I did not wish they had been better. But if they

had been much better they would not have been published. If the

formula had been a little less rigid, more of the writing of that

time might have survived. Some of us tried pretty hard to break out

of the formula, but we usually got caught and sent back. To exceed

the limits of a formula without destroying it is the dream of every

magazine writer who is not a hopeless hack.” And in a radio

discussion with Chandler, Ian Fleming said that Chandler offered

"some of the finest dialogue written in any prose today".

After Chandler's wife died, he began drinking

heavily and slid into a severe depression. He attempted suicide but

called the police before the attempt to tell them he was going to do

it. He died in 1959.

My final author of course needs no introduction to

anyone – mystery buff or not. Agatha Christie is almost as well

known as Santa Claus. She published sixty-six novels and fourteen

short story collections. She was initially unsuccessful in getting

published, but in 1920 “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” was

published, introducing the world to Hercule Poirot. The Guinness

Book of World Records lists Dame Agatha as the best selling author of

all time.

Much has been made of her ten day disappearance

after her husband asked for a divorce. A much maligned movie,

“Agatha,” was made – with a large disclaimer at the beginning –

with a fanciful explanation as to what occurred. It has never been

made public what happened in that ten day period.

In 1930 Dame Agatha married archeologist Sir Max

Mallowan, whom she met during an archaeological dig. Their marriage

lasted until Christie's death in 1976.

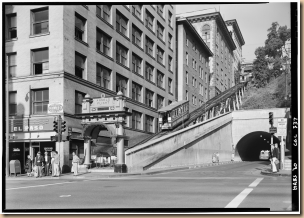

He was a big man but not more than six feet five inches tall and not wider than a beer truck. His arms hung loose at his sides and a forgotten cigar smoked between his enormous fingers. He was worth looking at. He wore a shaggy borsalino hat, a rough gray sports coat with white golf balls on it for buttons, a brown shirt, a yellow tie, pleated gray flannel slacks and alligator shoes with white explosions on the toes. From his outer breast pocket cascaded a show handkerchief of the same brilliant yellow as his tie. There were a couple of colored feathers tucked into the band of his hat, but he didn't really need them. Even on Central Avenue, not the quietest dressed street in the world, he looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.

He was a big man but not more than six feet five inches tall and not wider than a beer truck. His arms hung loose at his sides and a forgotten cigar smoked between his enormous fingers. He was worth looking at. He wore a shaggy borsalino hat, a rough gray sports coat with white golf balls on it for buttons, a brown shirt, a yellow tie, pleated gray flannel slacks and alligator shoes with white explosions on the toes. From his outer breast pocket cascaded a show handkerchief of the same brilliant yellow as his tie. There were a couple of colored feathers tucked into the band of his hat, but he didn't really need them. Even on Central Avenue, not the quietest dressed street in the world, he looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000037_00019] Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000037_00019]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-xzZWU1po5ag/Ve4QerHuDPI/AAAAAAAACoQ/MdwF_uLP7xg/Vortex-Kindle-Cover-FD3%252520--%252520Paul%252520D%252520Marks_thumb%25255B1%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)