|

| The Cleveland Park Library, Washington, D.C. |

Perhaps library checkouts are handled differently nowadays, and maybe that stamped sheet at the back of the book was just a relic (resident librarian Rob -- help me here!). But regardless, the experience got me to thinking: What happens to all of those books that people stop checking out from libraries? Are they all sold at used books fairs? And what happens to purchased books when they have been read by everyone in the family? Do all of them sit around on private bookshelves forever? I, for example, keep every book I have purchased and was very happy when e-books came along -- I was almost out of shelving space. But what are the options for the non-hoarder?

|

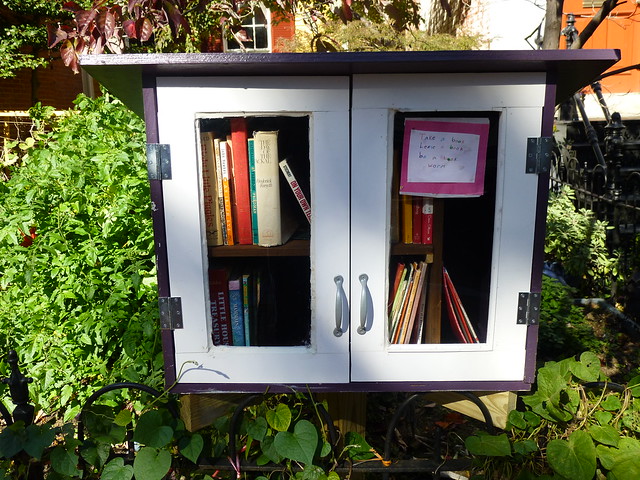

| A Micro Library in Capitol Hill, D.C. |

A newer take on this is the “micro library.” While it is sometimes difficult to trace the origins of new cultural waves one of the earliest organized deployments of micro libraries reportedly began in the U.K. From there the idea spread, including to the U.S. Here in Washington, D.C. you likely will not walk very far in any urban neighborhood without encountering a street-side micro library. These run the gamut from crude crates affixed to a post to carefully crafted dollhouse-like structures, each offering several shelves of books and a sign inviting passers-by to take a book and leave a book.

In New York City you may stumble upon something a bit more elegant. There a project that is the brain-child of urban architect John Locke involves the re-use of telephone booths, as he explained in a July, 2012 interview in World Literature Today.

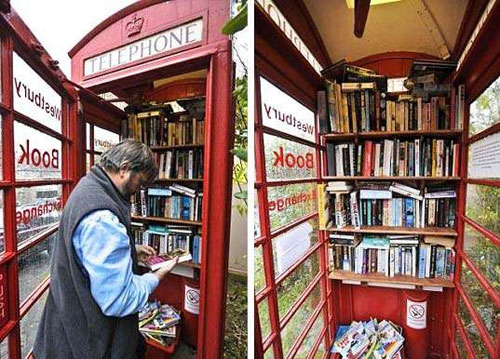

|

| Typical NYC Micro Library sharing a phone booth |

I was . . . drawn to the technological, and maybe even psychological, symmetry between physical books and phone booths. I think there is an innate feeling of loss toward both, in that one has already been rendered obsolete by a new technology—cellular phones—and the other is seemingly on the cusp of obsolescence as well, both through the proliferation of e-book readers and the general waning of literature as being part of the wider cultural discussion. And I think there is always a sense of hesitation, maybe even nostalgia, when something that once seemed so prominent and important begins to disappear.

Locke’s reaction to all of this, as shown in the picture, above, was to populate under utilized or even abandoned New York City phone booths with shelves of books. A similar approach has been used in England, where micro libraries have been established in iconic U.K. phonebooths. Once established, each micro library is largely free of supervision -- books are taken, books are left. Locke notes that each location predictably takes on characteristics of the community in which it is located -- the range of books that is available evolves and the overall character of the offerings changes in a manner that reflects the reading habits of the neighborhood.

|

| A phone booth micro library in the U.K. |

While the micro library movement began as a sort of guerrilla “occupy the streets” approach to sharing books, as noted above it now has at least the semblance of order, with organized locations and world-wide location maps. If you are interested in sharing books but find that all of this is still a little too organized for your own guerrilla soul there is yet another avenue for each of us to send forth our books after we have read them.

Back in 2001 Ron Hornbaker, software business owner and book lover, came up with an idea to share books in a slightly less organized and more individual way. As explained in his BookCrossings.com website, his flash of genius was to send each book out on its own. Hornbaker’s idea was that it would be both useful and fun to surreptitiously abandon a book in a public place -- coffee shop, restaurant, bus stop, what-have-you -- and then sit back and watch what happens.

How does this work in practice? Well, first the book is registered in advance at the BookCrossings web site. This is a simple process, easily accomplished on a home computer. Once the book is registered the site assigns it an individual tracking number. Before “planting” the book for adoption, the owner affixes an identification tag like the following one: (available for download either for free or for a nominal price from the BookCrossing web site) prior to release.

Then the now former owner of the book sits back, relaxes, and waits to see how far the book goes. Each recipient, as explained on the identification tags, is encouraged to report in and, if all goes well, each book can then be traced on its travels through various owners on the BookCrossing web site using the individual assigned tracking number. How is all of this working so far, almost thirteen years later? According to the Bookcrossing website “[t]here are currently 2,263,401 BookCrossers and 10,021,193 books travelling throughout 132 countries. Our community is changing the world and touching lives one book at a time.”

That copy of Ellery Queen’s The Origin of Evil has been sitting sedately on the shelf of the Cleveland Park library for almost 40 years. I've got books some on my own shelves that have been there even longer. Think where they could have traveled!

Books set all of us free. There are some interesting ways that we can return that favor.

Books set all of us free. There are some interesting ways that we can return that favor.

.jpg)