by William Burton McCormick

As I said in my listing of my favorite crime films of the 1930’s, lists are silly. Making lists, however, can be a useful exercise for authors studying a genre. At best, it forces serious analysis on what works and what doesn’t, allowing an author better perspective on the elements of a successful thriller or mystery. At worst, it is a wonderful excuse for watching and re-watching countless old films, re-appreciating classics and unearthing obscure gems.

So, here I am again with a new decade to discuss, the era of the Second World War, film noir’s first Golden Age, when authors like Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett held sway and English director Alfred Hitchcock burst onto the American scene (his previous films, including my 30’s top film The 39 Steps (1935) were made in England. Now Hitch had Hollywood budgets and stars at his disposal. Look out!). Warning! Spoilers are ahead.

The number of outstanding crime films in this decade was exponentially greater than the preceding one and reducing it to fifteen was a painful affair. A list of honorable mentions reads like a collection of classics and near-classics: The Mask of Dimitrios (1944), Key Largo (1948), Song of the Thin Man (1947), Mildred Pierce (1945), This Gun for Hire (1942), The Blue Dahlia (1946), Laura (1944), They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), The Naked City (1948), High Sierra (1941), Gaslight (1944), The Dark Corner (1946), I See A Dark Stranger (1946), Leave Her to Heaven (1945), Out of the Past (1947), and The Postman Always Rings Twice(1944).

Several legendary directors had multiple films I was forced to omit: Fritz Lang (whose M (1931) nearly topped my earlier list) had the excellent pictures The Woman in the Window (1944), Hangman Also Die! (1946) and Scarlet Street (1945) left off. Akira Kurosawa wrote and directed two fantastic crime films Drunken Angel (1948) and Stray Dog (1949) but they were unseen outside of Japan, and I use this as the flimsiest excuse to omit them. (For a discussion on Kurosawa’s crime films go here.)

Alfred Hitchcock, well-represented on this list, was productive enough to have several excellent films not make the cut: Saboteur (1942), Lifeboat (1944), Spellbound (1945), Rebecca (1940, his only career Best Picture winner), and Suspicion (1941, often called his ‘flawed masterpiece’ as producer David O. Selznick forced Hitch to change the ending and make Cary Grant’s character innocent, much to Grant’s chagrin who wanted to play a villain).

Carol Reed, who has a film high on this list, also produced two excellent thrillers I’d recommend: Odd Man Out (1947) and The Fallen Idol (1948). Orson Welles’s The Stranger (1946) was probably the most painful cut from this list, while his The Lady from Shanghai (1947) has scenes of absolute genius tempered by Welles’s typical money problems and egregious studio interference. (And Welles insisted his wife and costar Rita Hayworth cut her luxurious hair and bleach it blonde, a sin against humanity that must be penalized).

Lastly, several great films with crime elements but ultimately residing in other genres are excluded: Casablanca (1942, a romance), Arsenic and Old Lace (1945, a farce), To Be or Not to Be (1942, a war comedy), His Girl Friday (1940, a screwball comedy), Rebecca (1940, a gothic romance), and The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948, a Western).

All these films I watched or re-watched before composing this list. So, enough about what’s not here. On to our main event:

15. Gilda (1946)

15. Gilda (1946)

American gambler Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford) is hired by Ballin Mundson (George Maceady) to run his Buenos Aires casino and watch over Mundson’s rebellious wife Gilda (Rita Hayworth), who often cavorts with other very dangerous men. When two German mobsters seek control of the casino, Mundson fakes his own death leaving Johnny and Gilda to contend with each other and the mob. Hayworth’s Gilda is the very visual definition of a femme fatale. Her entrance in the film is legendary, as is her singing “Put the Blame on Mame” in a hormone-popping strapless black dress designed by Jean Louis, a performance still bewitching seventy-six years later. An Esquire photograph of Hayworth in that dress with “Gilda” stenciled above decorated the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb tested in July, 1946. The 23-kiloton bomb was the most powerful exploded up to that point and the decoration meant to honor Hayworth “as the world’s ultimate bombshell.” When Hayworth found out she was highly offended.

14. The Glass Key (1942)

The second of four films pairing Veronica Lake and Alan Ladd, The Glass Key edges out This Gun for Hire from the same year and The Blue Dahlia (1946) as the finest picture to feature both stars. Based on the Dashiell Hammett novel of the same name, The Glass Key tells the story of Ed Beaumont (Ladd), the “problem solver” for corrupt political boss Paul Madvig (Brian Donlevy). Madvig has fallen in love with Janet Henry (Lake), and is determined to get Janet’s father, Ralph Henry (Moroni Olsen), elected governor despite the objections of mob kingpin Nick Varna (Joseph Calleia). A tale of temptation in many forms, Ladd’s Beaumont stays loyal to Madvig despite sexual advances from Janet and bribes, threats and torture from Varna. As election day approaches the bodies pile up, including Ralph’s son Taylor (Richard Denning). Despite Ladd being third-billed, Beaumont is the film’s central character. The Glass Key was rushed through production to capitalize on the chemistry between Ladd and Lake in This Gun for Hire and Hammett’s name after The Maltese Falcon (1941) and the successful Thin Man series. The timing was right, and it paid off handsomely at the box office.

13. Rope (1948)

Inspired by the Leopold and Loeb murders, director Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope tells the story of two roommates Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger) who kill a friend (Dick Hogan) for the sheer intellectual thrill of it. They then host a party using an unlocked chest housing the body as a serving table. Among the guests are the victim’s father (Cedrick Hardwicke), fiancée (Joan Chandler) and their old prep school professor Rupert Cadell (James Stewart), whose gallows humor and promotion of Nietzschean superman theories greatly affected the killers in their youth. By the end of the night, Phillip is coming apart, Brandon is making threats and Rupert regrets his irresponsible teachings.

A modern BBC review called Rope “technically and socially bold.” This is certainly true. The characters of Brandon and Phillip are a homosexual couple which the film hints at often. In reality, Dall was gay, Farley bisexual, and Hitchcock hired openly gay writer Arthur Laurents to craft a screenplay with appropriate subtext (Laurents and Farley would begin an 18-month relationship soon after production). The character of Rupert was also supposed to be gay, though the hints more subtle. (There is no evidence Stewart knew he was playing a gay man.) A film in 1948 with three homosexual characters, two villains and the hero, was daring even if the Hays Code prevented mentioning homosexuality explicitly.

Technically, Hitchcock was also pushing the envelope. In his first color picture, he shot long, continuous scenes only limited by the amount of film that could be placed in camera. Hitch disguises the ends of these eleven-minute “long takes” by panning or tracking into objects and then starting again from the same position. Some of these seams are clumsy (especially when you know the trick) but it allowed the film to appear to play out in real time. This was influential on director Fred Zinnemann and producer Stanley Kramer, who would use the illusion of a real time story to great effect in High Noon (1952). Except for one exterior establishing shot, the entire movie takes place in Brandon’s and Phillip’s Manhattan apartment. Hitchcock’s experiments on how to tell a gripping thriller in static limited space in Rope and the equally confined Lifeboat (1944) would pave the way for a masterpiece of the form in 1954’s Rear Window.

12. Shadow of the Thin Man (1941)

The fourth Thin Man film keeps the winning streak alive. In San Francisco, Nick and Nora Charles (William Powell and Myrna Loy) head to the races only to find a jockey who has thrown a race was murdered. (“My, they’re strict at this track,” says Nora.) With the day at the races ruined, they head to a wrestling match where Paul Clarke (Barry Nelson) is framed for killing a reporter and Clarke’s girlfriend Molly (Donna Reed) pleads for help. Are the two murders connected? The trail leads to Claire Porter (Stella Adler, future founder of the Stella Adler Studio of Acting) who, failing to seduce Nick, tries to outsmart him and steal evidence. Twists, turns and much laughter ensue.

The best scenes include a brawl in a restaurant and a recurring joke where Nick’s underworld contacts mock Nora’s hat. Eagle-eyed viewers will spot Ava Gardner as an uncredited extra in one scene, her debut in film. (We’ll see more of Ava on this list soon.) The first Thin Man film not based on a Dashiell Hammett story or treatment and without a screenplay from the husband-wife team of Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich (who claimed they had exhausted every witticism they knew in the first three films) new writers Harry Kurnitz and Irving Brecher stepped in without missing a beat. It is also the first film after canine actor Skippy was retired and the role of Asta given to a descendent. More changes were ahead. Pearl Harbor was attacked two weeks after the film’s release and Loy would forgo acting to serve in the Red Cross as Director of Military and Naval Welfare, while Powell would be devastated by the death of his ex-wife Carol Lombard in a plane crash two months later. But never mind those grim future troubles. Put on your best screwy hat, order the seabass, and enjoy because “Baby, you’ve arrived.”

11. Green for Danger (1946)

11. Green for Danger (1946)

Based on the Christianna Brand novel of the same name, Green for Danger is a classic “closed environment” mystery set in an English countryside war hospital during the German bombings of 1944. In the first scene, we are witness to an operation performed by a staff of six people: surgeon Eden (Leo Genn), anesthetist Barnes (Trevor Howard), Sister Bates (Judy Campbell) and nurses Linley (Sally Gray), Woods (Megs Jenkins), and Sanson (Rosamund John). A voiceover tells us within five days “two of these people will be dead and one of them a murderer.” What follows is a tense mystery where duties and bombings force suspects together and ratchet up the anxiety to deliciously tortuous levels. This tension is nicely counter-balanced by humorous-but-clever Inspector Cockrill (Alastair Sim), who arrives to catch the murderer. Great fun.

10. Foreign Correspondent (1940)

After leaving London for Hollywood in 1939, director Alfred Hitchcock burst onto the American cinema scene with two films released in 1940 that would receive Academy Award Best Picture nominations: Rebecca (the winner) and Foreign Correspondent.

The latter is a cracking good thriller of Europe teetering towards war. American journalist John Jones (Joel McCrea) is sent to Europe to interview a Dutch diplomat (Albert Basserman) only to witness his assassination. Or was it faked? And if so, for what purposes? Adventure, international intrigue and a surprising amount of comedy follow.

This film has a plethora of memorable Hitchcockian visuals: the chase in the rain through an umbrella-packed square, the mysterious windmill that turns opposite direction of others, the assassination on the steps mimicked by Francis Ford Coppola in the Godfather and Hitch’s first great set piece for American audiences, a plane shot down in the stormy Atlantic where the survivors cling to the wings as the waves wash over them.

After filming was complete, Hitch visited England and found the German blitz was soon to come. Back in Hollywood, he hired Ben Hecht to write a new closing scene where McCrea’s reporter broadcasts a warning to the world. It impressed even the enemy. German Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels called Foreign Correspondent "A masterpiece of propaganda, a first-class production which no doubt will make a certain impression upon the broad masses of the people in enemy countries". Hitch was fighting Nazi propaganda fire with a fire of his own. Rebecca may have taken home the Oscar, but for my money Foreign Correspondent is the better film. It’s certainly more reflective of what was on Hitchcock’s mind in 1940.

9. White Heat (1949)

Possibly James Cagney’s greatest film, each act of White Heat explores a different crime subgenre – gangster, prison, heist. Cagney plays mobster Cody Jarrett, a psychotic Mama’s boy worthy of the later Bruno Antony or ;[;[Norman Bates. After killing four men in a train robbery, Jarrett confesses to a lesser crime committed elsewhere to give him a false alibi for the murders. While serving a year in prison, members of his gang plot against him and the group is infiltrated by an undercover agent (Edmund O’Brian). After Jarrett’s release, they undertake a payroll robbery at a chemical plant unaware of the traitors and lawman in their midst. A perennial entry on all-time great films lists, White Heat is one of the darkest masterpieces to come out of the ‘40’s. And that ending. Wow! Say it all together: “Made it, Ma! Top of the world!” Boom!

8. The Thin Man Goes Home (1945)

Nick and Nora Charles (William Powell and Myrna Loy, as if you didn’t know by now) leave Nicky Jr behind and visit Nick’s parents (Harry Davenport and Lucile Watson) in rural New England. Word quickly circulates that the famous detective is on a case, rumors fanned by Nora to impress Nick’s father, who thinks little of sleuthing and wanted his son to be a doctor like he is. Then a man is shot dead on the Charles’ doorstep and the fictious case becomes real. One of the best in the series, the cast of colorful small-town suspects makes it the most engaging mystery since the 1934 original.

The fifth film, it was the first entry without series director W.S. Van Dyke who died in 1943. With Loy off supporting the war effort, MGM announced in pre-production that Irene Dunne would be cast as Nora. Horrified fans started a mail campaign demanding Loy. As Powell said: “The fans wanted Myrna, and they didn't want anyone else...And I wanted Myrna, too…I've never seen a girl so popular with so many people.” When Loy did return (her only film of the war years) she donated her salary to the war effort. The Thin Man Goes Home would be followed by a final sequel in Song of the Thin Man (1947) a darker, noirish picture which could have made this list too. Is there any mystery series (or comedy or romance series) that is this good, this long? If you can think of one put it in the comments below.

7. The Killers (1946)

7. The Killers (1946)

Expanded from an Ernest Hemingway short story of the same name The Killers starts out in tense and riveting fashion. Two hitmen (Charles McGraw and William Conrad) arrive in Brentwood, New Jersey and murder a gas station attendant nicknamed “the Swede” (Burt Lancaster). Insurance investigator Jim Reardon (Edmund O’Brien) looking for a motive for the killings, delves into the Swede’s past, unearthing a rogue’s galleries of suspects including gangster-gone-straight “Big Jim” Colfax (Albert Dekker) and old flame Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner).

As Reardon moves closer to the truth, the Swede’s story is told in Citizen Kane-style flashbacks. Lancaster, terrific in his film debut, and Gardner, given a chance to shine after years of bit parts, both deservedly became stars. The music written to accompany the hitmen at every appearance would later become the Dragnet theme.

With a screenplay by Anthony Veiller (and an uncredited rewrite by John Huston), The Killers would go on to beat out such other classics as Notorious and The Big Sleep for the Edgar Award for Best Mystery Picture. But the truest praise came from Hemingway himself who called The Killers “The only good picture ever made of a story of mine.”

6. The Big Sleep (1945)

6. The Big Sleep (1945)

“Ah ha!” you say, you’ve caught an error. Every cinephile knows The Big Sleep (based on the 1939 Raymond Chandler novel, with a screenplay by William Faulkner and starring Humphrey Bogart as detective Philip Marlowe and Lauren Bacall as widow Vivian Rutledge) came out in 1946, not 1945. Well, have faith true believers, this requires an explanation. When director Howard Hawks filmed The Big Sleep, World War II was coming to a close. Warner Bros. Pictures had a backlog of war films the studio wanted to release before the fighting ceased. So, with the film in the can, The Big Sleep’s theater distribution was pushed back. Warner Bros. did, however, play it to Allied servicemen fighting in the South Pacific in early 1945.

Then a funny thing happened. Thanks To Have and Have Not, Bogie and Bacall became Hollywood’s hottest couple on and off screen. Bacall’s agent asked if Hawks and the studio would be willing to film new scenes to capitalize on their chemistry and increase the role for Bacall’s character. Twenty minutes of new footage were shot, mostly featuring the couple exchanging sexually charged banter. Scenes were re-ordered, others removed, and two key characters dropped to accommodate the new footage.

This version, released in 1946, was the classic we’ve all come to know. A terrific film, but even its most fanatic admirers will admit the plot is confusing. (When Jack Warner cabled Chandler asking if a character was murdered or had killed himself, the author replied “Dammit, I don’t know either!”).

In the 1990’s, a copy of the original 1945 cut was found in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Hugh Hefner, a fan of Chandler’s work, paid for a restoration and theater distribution of the 1945 print. Since then, the debate has raged: ’45 or ’46? Roger Ebert preferred ’46, caring more for “feel” than story. The Washington Post thought them both masterpieces but very different films. Me? I watched both versions again for this article. I’ll side with Hef and the servicemen. There is enough interplay between Bogie and Bacall in the ‘45 cut for my taste and with the scenes in proper order and those two other characters present, the plot makes much more sense. Have you seen both versions? If so, which do you prefer? Please tell me in the comments.

5. Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

One of Hitchcock’s finest films of any decade, Shadow of a Doubt is the story of Charlotte “Charlie” Newton (Teresa Wright) and her visiting uncle Charles “Charlie” Oakley (Joseph Cotten). The two Charlies share a special bond, one that is tested by the terrible secrets Uncle Charlie brings with him when he arrives at the family home in Santa Rosa, California.

Wright’s Charlie is easily my favorite Hitchcock heroine, and the actress is a joy to watch in the role. No icy blonde bound for humiliation, the character is a plucky, warm, and highly intelligent brunette who follows the clues to discover what her uncle really has been up to on the East Coast with all those “merry widows” who seem to be dying off. When the secrets are revealed, she matches wits with her uncle and ultimately defeats him while sheltering her family from the horrible truth.

Wright’s Charlie is easily my favorite Hitchcock heroine, and the actress is a joy to watch in the role. No icy blonde bound for humiliation, the character is a plucky, warm, and highly intelligent brunette who follows the clues to discover what her uncle really has been up to on the East Coast with all those “merry widows” who seem to be dying off. When the secrets are revealed, she matches wits with her uncle and ultimately defeats him while sheltering her family from the horrible truth.

That family is excellently portrayed and I’m particularly fond of Henry Travers as her father, a bored banker and mystery fan who plots murderous scenarios with family friend Herbie (Hume Cronyn) over the dinner table. Their humorously imagined killings are a perfect balance to the real threat Uncle Charlie has brought into their home. Cotten is flawless in the role, charming enough to fool everyone, but his niece, and chillingly sinister when cornered. Hitchcock would say for the rest of his life this was his favorite of all his films. Who can argue with the Master? Well, maybe I’d dare to argue (a little) as I have another Hitchcock film at number four.

.jpg)

4. Notorious (1946)

Poor Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman). She loves American agent T.R. Devlin (Cary Grant) but he wants her to sleep with and ultimately marry another man, Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), so she can spy on Sebastian and his circle of German conspirators in Rio de Janeiro.

Alicia obeys partially because she is a patriot and wants to stop the Nazis from restarting the German war machine, partly because her German-American father was a spy and traitor and she wants to atone for his actions, but mostly because she loves Devlin and he asks her to do this. Devlin, while directing her actions, resents her obeying his carnal orders and treats her in a jealous and passive aggressive manner. How dark and twisted is that? But it’s for national security, right?

Sebastian, despite being implicitly a Nazi (the word is never used), is portrayed as a sympathetic character for a villain. He truly loves Alicia, and she is using that love to destroy him. What it amounts to his one of the blackest and most suspenseful love triangles ever put to screen.

Notorious marks a major development in Hitchcock’s career. Midway through pre-production, he finally jettisoned producer David O. Selznick. From here on out, Hitch would produce his own films (as well as direct and develop the stories with his writers). With this freedom, starting with Notorious his movies would become more psychological in focus, an aspect that has given his best work a true timeliness. There is always something uncomfortable going on underneath the surface now.

Not that the magic is all subtext, visual storytelling remained a strength. For example, the legendary tracking shot from the top of a high staircase down to a key in Alicia’s hand far below. (A prop Bergman would keep as a memento). Or one of the most famous MacGuffin’s in history, the uranium ore that Sebastian is storing in the wine cellar, implying his team is working on an atomic bomb. (Notorious was filmed shortly before the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the American government was very leery about uranium references in the media.) Hitchcock claimed he and his screenwriter Ben Hecht were followed by the FBI during shooting.)

How good is Hitchcock at pulling the strings in Notorious? Consider this. It has no gunfights, no chase scenes, no onscreen murders, not a punch thrown or shot fired, yet it undoubtedly a superb example of the thriller genre. How? It’s all psychology and suspense. The Master playing the audience like a violin. Critic Roger Ebert regarded Notorious as Hitchcock’s best work and one of the ten best films of all time.

3. Double Indemnity (1944)

I’m glad I doubled down on Double Indemnity. The first time I viewed Billy Wilder’s film, years ago, it would have not made this list. Having grown up watching reruns of My Three Sons, and Disney live action fair like Follow Me Boys! and The Absent-Minded Professor, Fred MacMurray to me was a gentle, fatherly everyman not a murderous heel spouting risqué dialogue as he is here. This really threw me.

And Barbara Stanwyck in a cheap wig was not as dangerously beguiling as femme fatale sirens like Veronica Lake, Rita Hayworth, Lana Turner or Ava Gardner. I didn’t understand why MacMurray’s insurance salesman would destroy his life for her. (Wilder would say that the phoniness of the wig was meant to hint at the phoniness of the character beneath it.)

On a second viewing, those biases fell aside. This is one great film, rocketing up to its current position. The best of a noir sub-subgenre featuring evil women seducing weak men to gain help murdering husbands or sugar daddies, this trope is found in The Woman in the Window (1944), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), and countless other films to this day. (Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine editor Janet Hutchings once told me this plotline is the most frequently submitted to her magazine. One wonders how many are influenced by Double Indemnity?)

The difference is in the high quality of the performances by MacMurray and Stanwyck (once all biases and wigs are ignored), a fantastic screenplay by Wilder and Raymond Chandler (based on the James M. Cain novel of the same name), and perfect direction by Wilder, with suspenseful sequences that may equal anything Hitchcock did in the 1940’s. (Not an easy admission for a Hitchcock devotee like me.) Among these are a sequence on a train where MacMurray cannot find privacy to fake a suicide, or the moment after dumping the body when Barbara’s car refuses to start, or when a character places a gun under a pillow that you know will be used later, or the extended tension when MacMurray’s friend and colleague, insurance investigator Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson, never better), recruits him to help solve the murder MacMurray himself committed. I could go on forever. Even a conversation in a grocery store is fraught with danger and suspense. For many, this film is the apex of film noir’s Golden Age. I can see why.

The last two films, flipped back and forth for the top position a half-dozen times during the drafting of this list. Oh, the agony, we arbitrary list makers go through! But the piece has to be finished, so the positions must be set. He takes a breath. So…

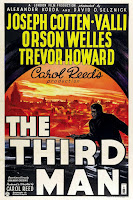

2. The Third Man (1949)

“The dead are happier dead,” remarks a character in The Third Man. The statement reflects not only the speaker’s sociopathic views, but the exhaustion of a war weary Europe in the late ;40s. Director Carol Reed made two excellent thrillers in the years preceding this film, Odd Man Out (1947, Roman Polanski’s favorite film), and Fallen Idol (1948), but The Third Man is his masterpiece.

Written by the great Graham Greene (who drafted both screenplay and novella), The Third Man tells the story of Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten), a naïve American Western author who arrives in post-WWII Vienna to work for his old friend Harry Lime (Orson Welles), only to discover that Lime was killed by a passing car days before Holly’s arrival.

Martins finds the accident suspicious and seeks to discuss it with two witnesses (Ernst Deutch and Siegfried Breuer) who carried Lime’s body away and a mysterious “third man” who was also at the scene. His search for this third man brings him into contact with Lime’s girlfriend, actress Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), a German-speaking Czech who lives in dread of being deported to the Soviet Zone, and British military police officer Major Calloway (Trevor Howard) who tells Martins that Lime was an unscrupulous raconteur operating in all zones of divided Vienna.

In an era when most filming was done on sets and studio backlots, The Third Man was filmed primarily onsite in still-rebuilding Vienna, giving it greater realism and vibrancy than other pictures of the time. Indeed, the divided city has an authentic character as strong as any flesh and blood actor. It is a beautiful film for the eyes and ears with harsh lighting and Dutch angles from expressionist cinematographer Robert Krasker and a distinctive score by local zither player Anton Karas (whom Reed discovered playing one night in a Vienna wine-garden and invited him to score his film.)

Despite rumors, Welles did not direct any of the second unit filming, though he did provide the famous “cuckoo clock” line. The actor performances are starling modern, and Greene’s dialogue is imbibed with depth, ironic humor and a real despair. A speech by a villain looking down from the heights of the Wiener Riesenrad Ferris wheel, the people below resembling mere dots, is one of the most memorable and chilling ever given. “Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you £20,000 for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money? Or would calculate how many dots you could afford to spare? Free of income tax.”

The rare thriller to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, The Third Man was voted by the British Film Institute as the greatest British film of all time (of any genre or era). They aren’t wrong. I love this film and can’t believe The Third Man is second to anything.

But there is another film I love as much, and it defines crime cinema in the ‘40’s like no other.

Ah, that black bird. The greatest MacGuffin of all. John Huston’s directorial debut was the third filming of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel, but this is definitive. Those other films took liberties with the story and were of mixed success, so Huston decided “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it” and writing the screenplay himself, followed the book scene-for-scene, dialogue-for-dialogue.

It was an enormous hit launching Huston’s career as both director and screenwriter and turning B-list gangster actor Humphrey Bogart into a major star. (Coupled with Casablanca released the next year Bogart was on a fast track to becoming a Hollywood icon.) More than any other film, it ushered in the era of the film noir and Sam Spade (Bogart) became the archetype for a hardboiled detective. The Maltese Falcon tells, in essence, two interlocking stories: one is a mystery about who killed Spade’s detective partner Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan), the other is a game of wits with a quartet of crooks seeking a statue of a falcon which is supposedly encrusted with priceless jewels beneath its enameled skin.

With one of history’s most sublime casts, each of those actors perfectly defines their crooked characters: the duplicitous femme fatale Miss Wonderly/Brigid O'Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), the over-dressed, treacherous fop Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), the gluttonous, talkative criminal leader Kasper Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet) and the unhinged youthful gunman Wilmer Cook (Elisha Cook, Jr.).

To watch the five main characters, try to outmaneuver each other for the priceless bird, each spouting Hammett’s snappy dialogue, is one of the great joys of cinema. At the center of the storm is Spade juggling crooks, police and Miles' widow Iva (Gladys George) who is infatuated with Sam. He trusts nobody and plays it straight with no one except his secretary/side kick Effie Perrine (Lee Patrick).

Bogart’s other great film detective, Philip Marlowe, may have gone down the “mean streets”, but Sam Spade is plenty mean himself. As in the book, Sam keeps his thoughts private from other characters and audience alike, and much of the tension comes from wondering if Spade will fall in with the crooks and become one of them. He is on the edge of being an antihero. It’s a corrupt world, but is our hero corrupt?

At the denouncement, Spade steps back from the abyss at last revealing his cards and telling O'Shaughnessy: “Don’t be too sure I’m as crooked as I’m supposed to be. That sort of reputation might be good business, brining high-priced jobs and making it easier to deal with the enemy.”

In a sentimental age, when the male and female leads were supposed to go off together hand-in-hand (even Notorious, as black as it is, ends with Grant and Bergman together), The Maltese Falcon throws a curve. When O'Shaughnessy admits to killing Miles, Spade tells his lover: “Yes, Angel, I’m gonna send you over. That means if you’re a good girl, you’ll be out in 20 years. I’ll be waiting for you. If they hang you, I’ll always remember you.” It begins a speech many can recite from memory. Some film historians think Psycho (1960) is the great severing point between the Age of Sentimentality and the Age of Sensation in cinema. I’ll maintain that The Maltese Falcon did that nineteen year earlier.

Why is The Maltese Falcon number one? I’ll quote the film’s last line, one improvised by Huston from Shakespeare on the set.

“It’s the stuff dreams are made of.”

Any films I missed either on the list or Honorable Mentions? Give me your own favorites from the 40’s.

Any films I missed either on the list or Honorable Mentions? Give me your own favorites from the 40’s.

Now’s the time when the blog author normally plugs some work. I like to keep my shameless promotions relevant to the article. Fortunately, I had a thriller short story set in 1943 published this year. “Locked-In” was in the January/February 2022 issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. If you liked this article, please revisit my story in a back issue or Magzter or wherever you read AHMM and tell me if it fits in with the era. You can read Rob Lopresti’s review of “Locked-In” here.